Aloïse (Aloïse Corbaz dite)

Bonfand Alain, Porret-Forel Jacqueline, Tossatto Guy, Aloïse, Paris, La Différence, 1989

→Porret-Forel Jacqueline, Aloïse et le théâtre de l’univers, Geneva, A. Skira, 1993

→Porret-Forel Jacqueline, La voleuse de mappemonde – Les écrits d’Aloïse, Geneva, Éditions Zoé, 2004

Aloïse Corbaz, Département culturel de Bayer, Leverkusen, 22 September – 27 October 1996

→Aloïse. Comme un papillon sur elle, Borderless Art Museum NO-MA, Omihachiman, 3 February – 10 May 2009 ; Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 15 May – 16 August 2009; Hokkaido Asahikawa Museum of Art, Asahikawa, 24 October 2009 – 14 January 2010 ; Museum Gugging, Klosterneuburg, 26 March – 26 September 2010

→Aloïse Corbaz en constellation, LaM, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, 14 February – 10 May 2015

Swiss artist.

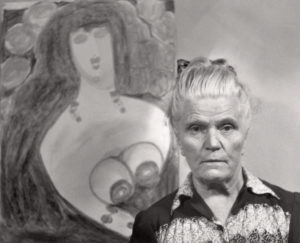

Now considered one of the major figures of art brut, Aloïse is well known to a wider audience today thanks to the eponymous 1975 film by Liliane de Kermadec (born 1928), starring Delphine Seyrig. Aloïse’s artistic practice is inseparably linked to her disease – schizophrenia – and to her internment in a psychiatric ward for 46 years. Born into a family of modest means, she was only eleven when she lost her mother, who had been exhausted by multiple pregnancies; her older sister, Marguerite, thus took over the running of the household with an iron fist. While day-to-day life was difficult, in her works the artist nevertheless occasionally evokes the colours of the Easter eggs, and Christmas baubles and gifts of her childhood. All of the members of her family sang or played music. The young Aloïse, gifted with a lovely voice, was passionate about singing and was very well versed in the operatic repertoire; she took music lessons with the organist of Lausanne Cathedral and was a member of the choir. She dreamed briefly of becoming an opera singer, but was unable to fulfil this ambition. After her certificate of studies, obtained in 1904, she attended the professional dressmaking school in Lausanne. In 1911, it would appear that she had a romantic relationship with a theology student, which Marguerite sternly forced her to break off. Undoubtedly as a result of this break up, she left for Germany, where she was hired as a tutor for a family in Leipzig, then as a children’s governess in Potsdam at the home of the chaplain of Kaiser Wilhelm II. While there, she dreamed up an entirely imaginary passion for the Kaiser. However, she was forced by the outbreak of World War I to return to Lausanne in 1914. To her family’s great surprise, she affirmed her position as a pacifist and anti-militarist. During this time, she would spend a great deal of time alone writing religious songs, and her behaviour became increasingly inflamed: she believed she was pregnant with Christ’s child; she would scream in the street, claiming that someone was trying to murder her and that her children had been stolen. As a result, she was committed to the psychiatric ward of Cery, near Lausanne, in 1918. After a difficult start, she gradually grew accustomed to her new life and was subsequently transferred to the Rosière asylum in Gimel-sur-Morges, an establishment reserved for incurable patients and where she was to remain for the rest of her life.

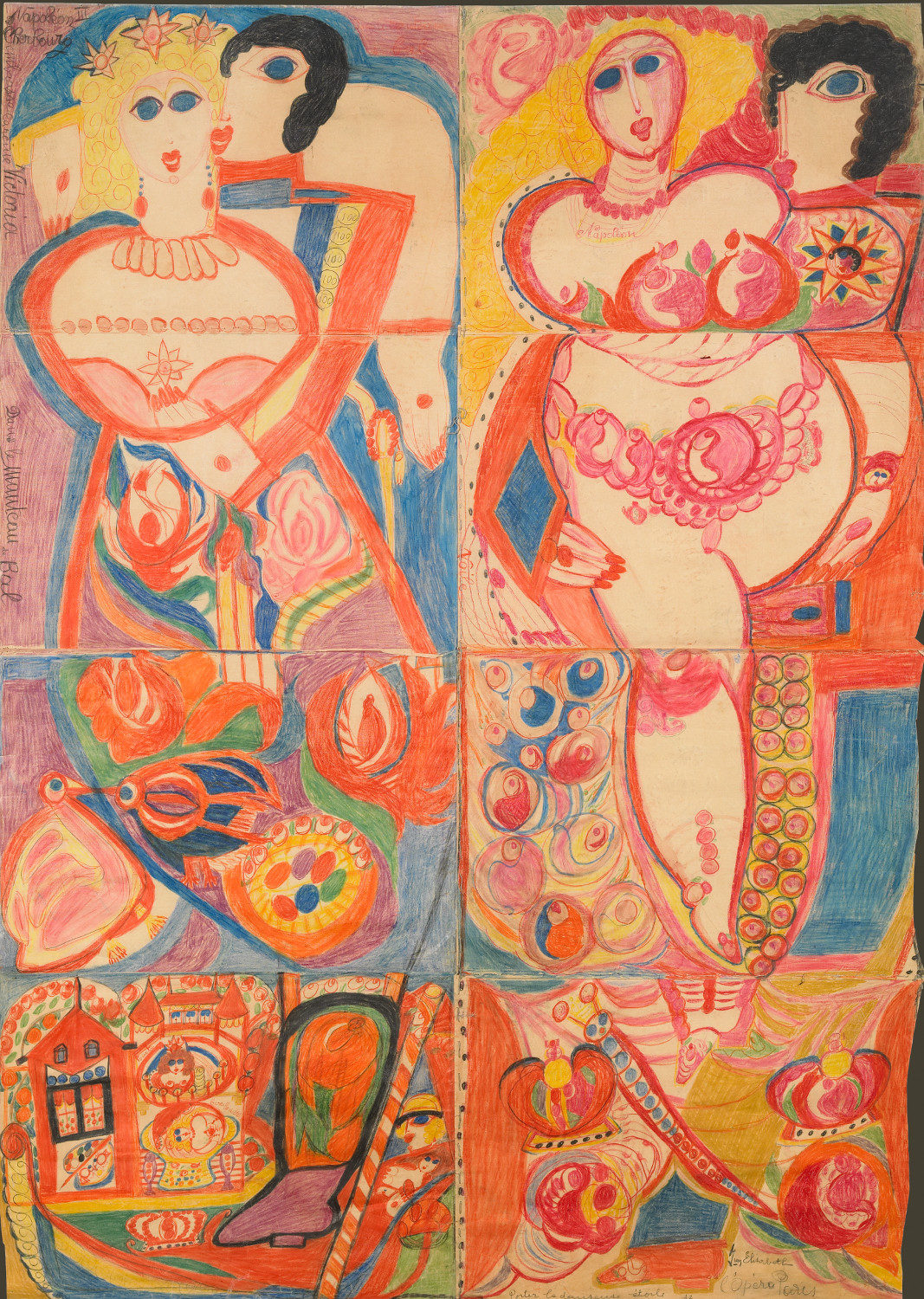

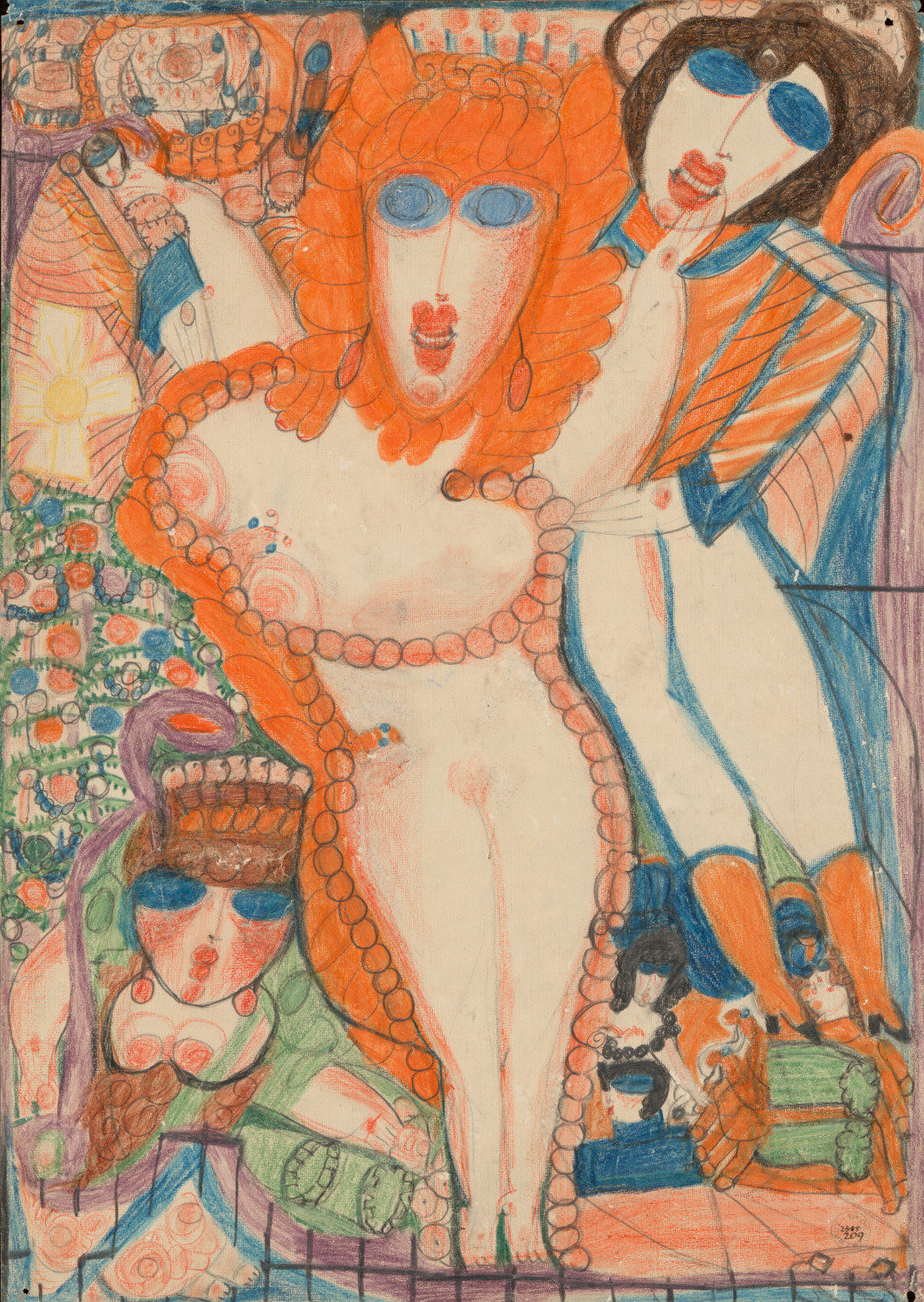

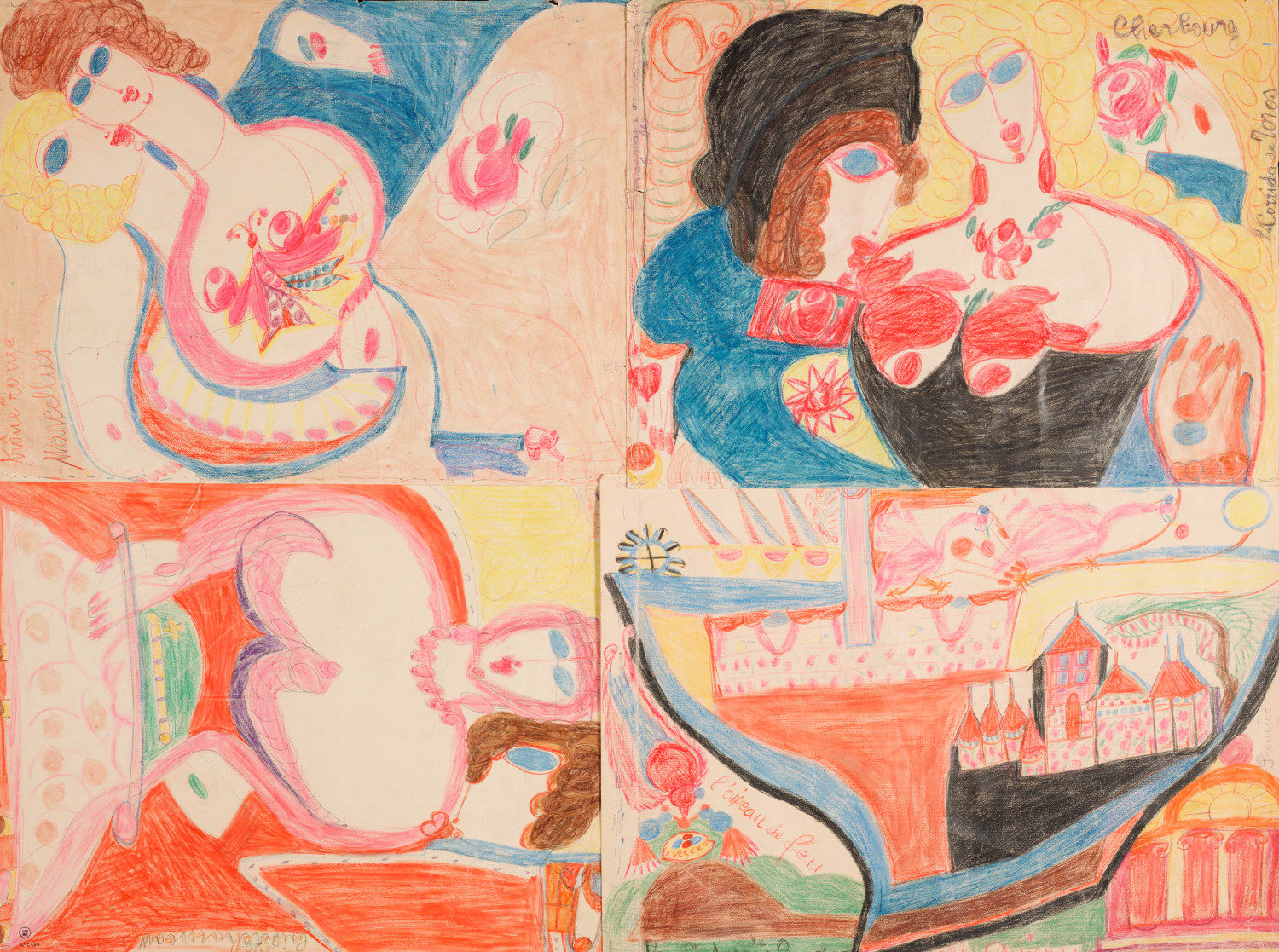

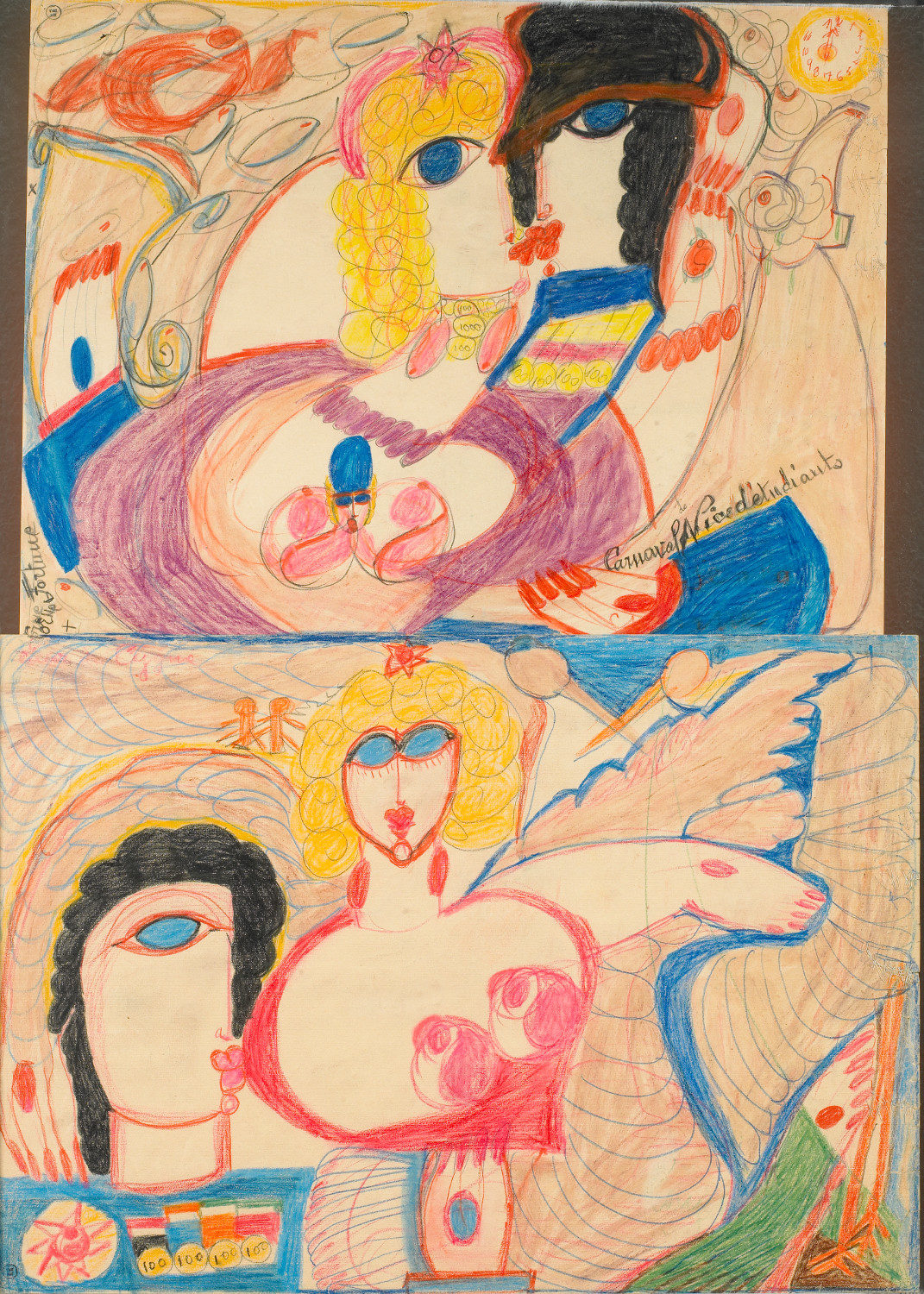

The drawings that she started making, probably from around 1920, enabled her to overcome illness and internment. At first she drew in hiding, using materials she found in trashcans: fragments of gridded paper, old illustrated postcards, brown paper, old invoices, and bits of cardboard packaging. A stroke of pencil would transform a shape or a detail from the illustrated page into a character. These materials were flattened, smoothed out, and patched together using white cotton and red thread; the stitching, which was sometimes very elaborate, emphasises and determines many of the design elements. The very structure of the paper itself seems to dictate motifs: one piece of packaging, from a butcher’s shop, led her to represent the figure of Hitler. The sheets of paper sewn together enabled her to create very large drawings, which she kept in rolls. She would work on both sides with pencil and crayons, taking up all available space. The world she created is populated by human figures, animals, flowers, and fruit in theatrical stagings that, for her, took on very specific meanings: some of her subjects mimic gestures and poses inspired by illustrated magazines, or adopt the attributes and postures taken from the actors of ritualised theatre or opera; the attitudes are hieratic, the faces inexpressive and immobile, or, conversely, contorted like the masks of classical tragedy. Theatre, opera, and amorous couples adorn this cosmogony, which developed powerful erotic forms. Until 1936, no one paid much attention to Aloïse’s artistic production, which had been almost entirely destroyed. Professor Hans Steck, who became the director of the Cery hospital, along with doctor Jacqueline Porret-Forel and several others, later attended to the conservation of her drawings and began procuring her the equipment she needed, up until her death. Jean Dubuffet exhibited her work in Paris in 1948 within the framework of the Compagnie de l’art brut, then in 1949 in the exhibition L’Art brut préféré aux arts culturels. In 1963, a year before her death, the artist visited the exhibition Les Femmes suisses peintres et sculpteurs, held at the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, where she was the guest of honour.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018