Anna-Eva Bergman

Lamothe Christine, Anna-Eva Bergman, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2011

→Abadie Daniel (dir.), Anna-Eva Bergman (1909-1987). Rétrospective, exh. cat., Musée des Beaux-Arts, Carcassonne (10 June–15 September), Carcassonne, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1988

→Moe Ole Henrik; Lamothe Christine; Hinsch Luce (ed.), Pistes, Antibes, Fondation Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman, 1999

Anna-Eva Bergman, La Galerie de France, Paris, 1958/1962/1968/1977

→Anna-Eva Bergman (1909-1987). Rétropective, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, November 1977–Janvuary 1978

→Anna-Eva Bergman. L’atelier d’Antibes (1973-1987), Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Biguan, 5 March–4 June 2017

French-Norwegian painter and engraver.

Anna-Eva Bergman was born in Stockholm on 29 May 1909 to a Swedish father and Norwegian mother. Her childhood was a chaotic one, and she was only six months old when her parents separated. Her mother entrusted her to her maternal aunts in Norway, with whom she lived until 1925. A.-E. Bergman showed a very early talent for drawing. With her bold strokes and great sense of observation, she began drawing unusual figures in burlesque situations. Her gift led her to start studying at the age of sixteen at the School of Applied Arts in Oslo, then the next year at the Academy of Fine Arts. Much of her work was influenced by Edvard Munch at the time, and she painted landscapes inspired by Symbolism.

In 1928, A.-E. Bergman moved with her mother to Austria, where the experimental teaching methods of Professor Steinhof at the Kunstgewerbeschule marked her deeply. This was probably when she painted her first abstract paintings, which have since been lost. After three months in Austria, she fell dangerously ill and was hospitalised for serious digestive disorders, which she would suffer from her whole life. After her convalescence on the Côte d’Azur, she moved to Paris in April 1929 to study at André Lothe’s academy, then at the Académie Scandinave, where she met the young German painter Hans Hartung, whom she married six months later, thus acquiring German citizenship. During this time, her style was greatly influenced by the magic realism of artists from the German school Neue Sachlichkeit, such as Georg Gross and Otto Dix. However, she approached characters from a more ironical than critical angle, playfully observing the foibles of her contemporaries – middle-class people, couples, families, children, old people, and tourists. Some of her drawings, presented in 1932 at her first solo exhibition at the Heinrich Kühl Gallery in Dresden, then in Norway at the famous Blomqvist Gallery in Oslo, were published in Viennese periodicals.

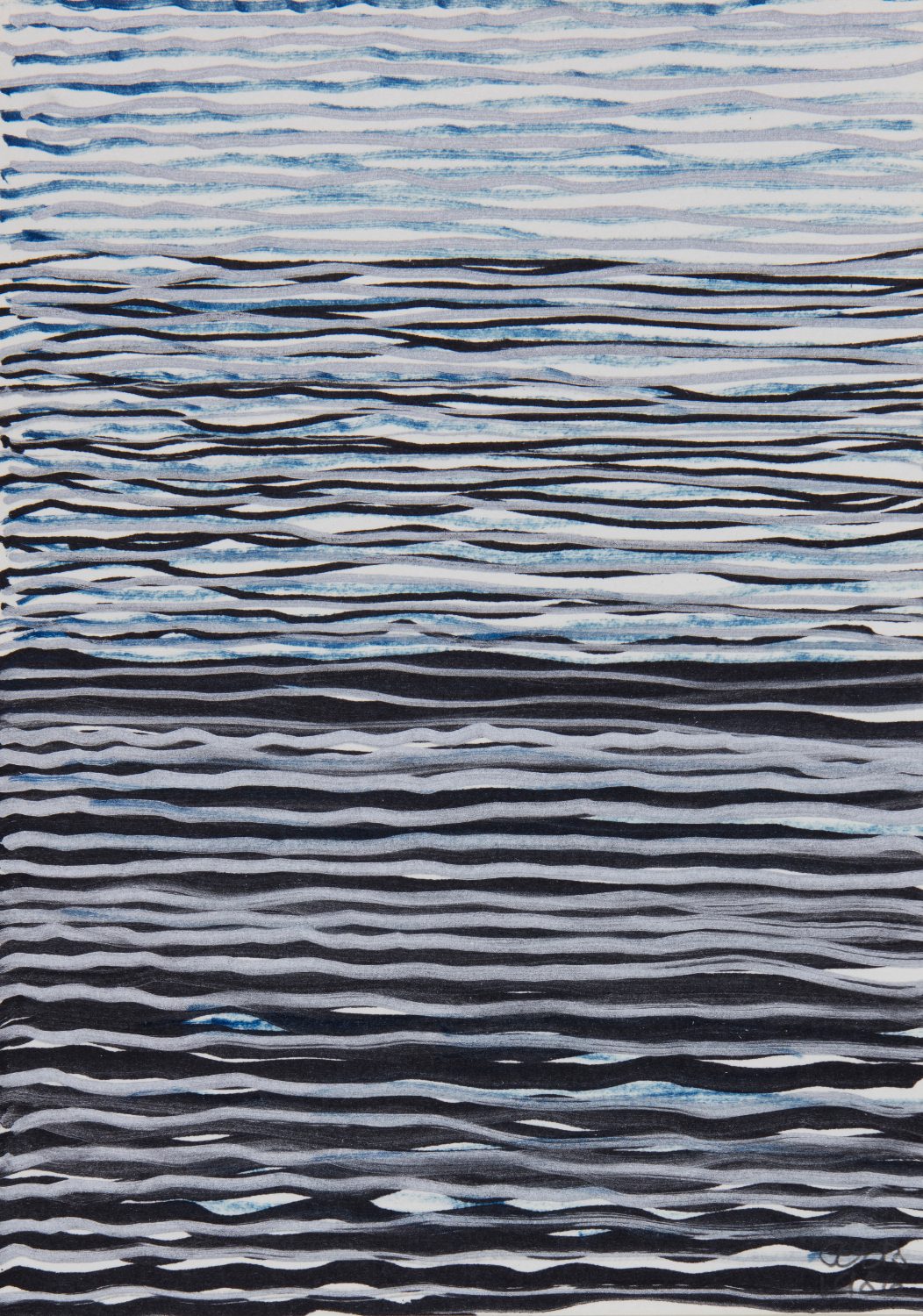

A.-E. Bergman pursued her activity as an illustrator and press artist until the late 1940s, before converting exclusively to abstraction. From then on, she would uncompromisingly judge the quality of her past work, going so far as to consider it worthless. The economic crisis and rise of Nazism forced Hans and A.-E. Bergman to leave Germany. They decided to settle on the island of Minorca. During her time in Spain from late 1932 to 1934, A.-E. Bergman continued her work as an illustrator and drew many satirical cartoons denouncing the rise of Nazism. She also drew geometrical seascapes and cityscapes, which prefigured the essential shapes and pure, clean lines and surfaces that she would later paint. This happy chapter in A.-E. Bergman’s life was short-lived. Hans and A.-E. Bergman were suspected of espionage by a young republic wary of Germans and forced to leave Spain. The following years were marked by illness and long hospitalisations in Berlin and Oslo. Her relationship with Hans suffered from illness and pressure from her mother, who wished to protect her daughter from the dangers of her German citizenship as the war loomed. She separated from Hans and the couple divorced in 1938, whereupon A.-E. Bergman returned to her childhood country and reacquired Norwegian citizenship.

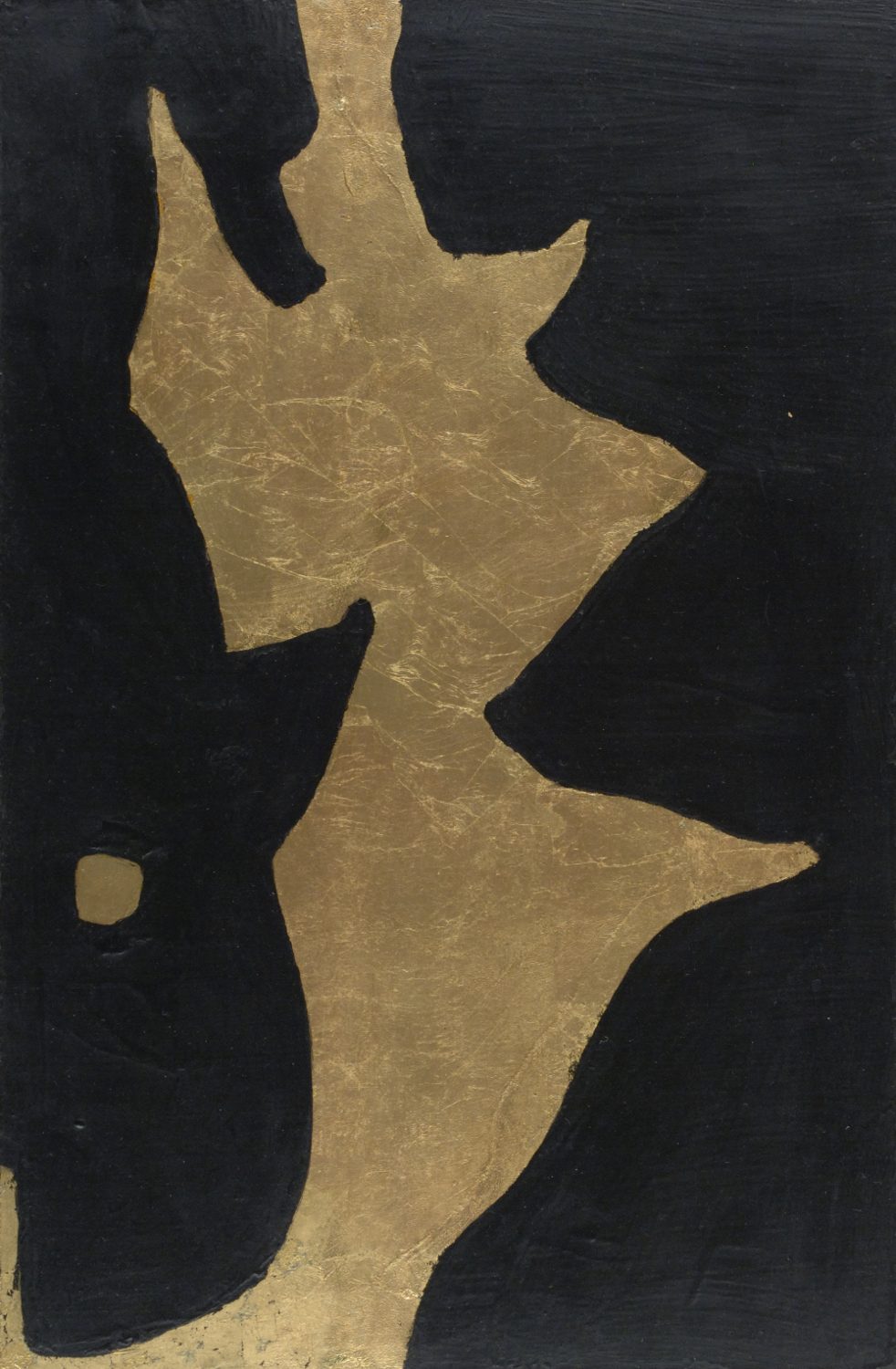

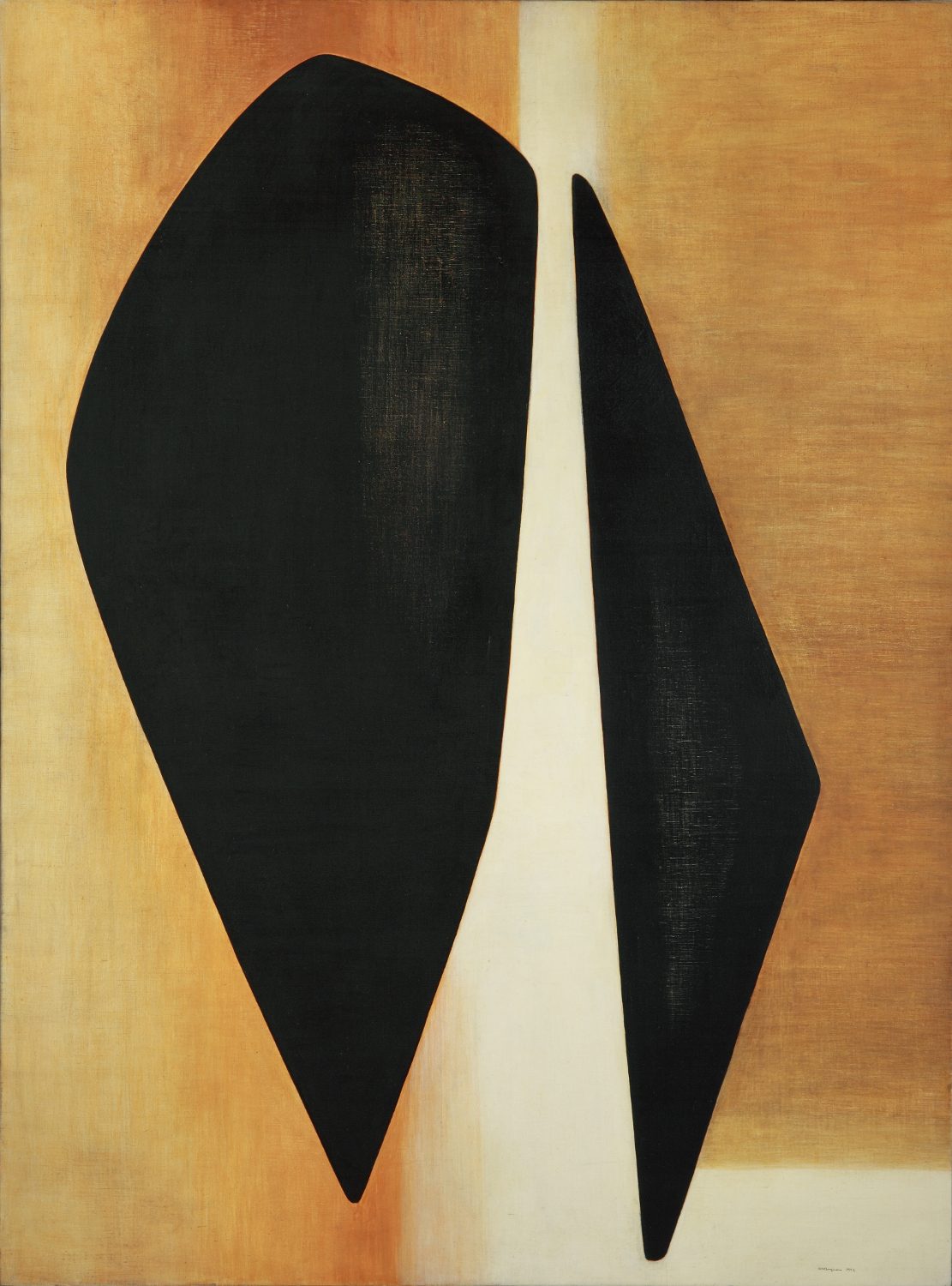

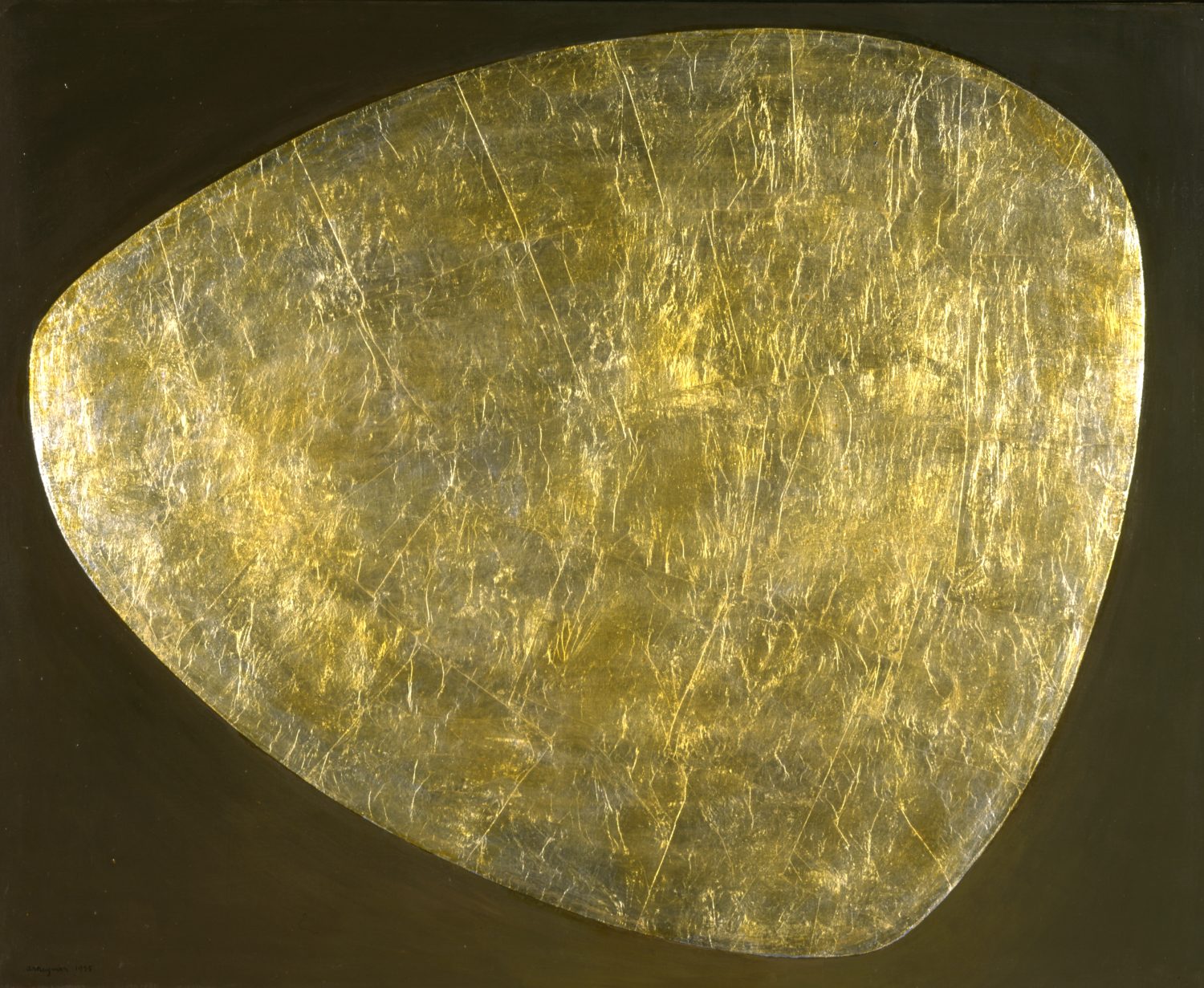

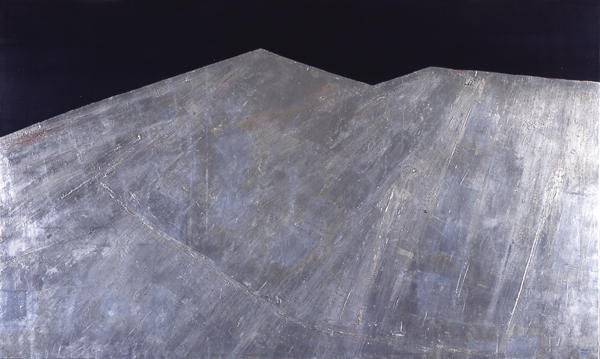

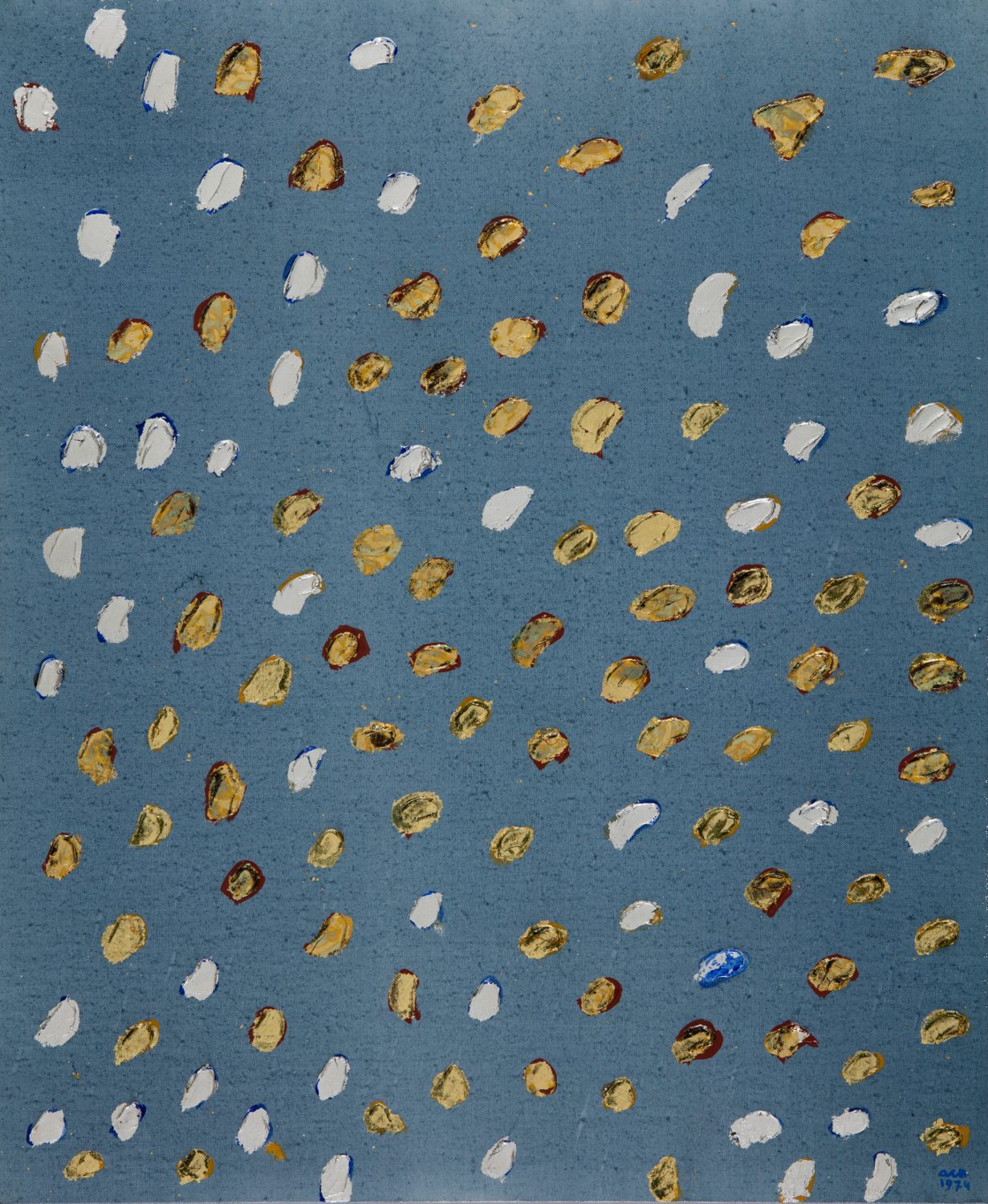

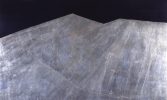

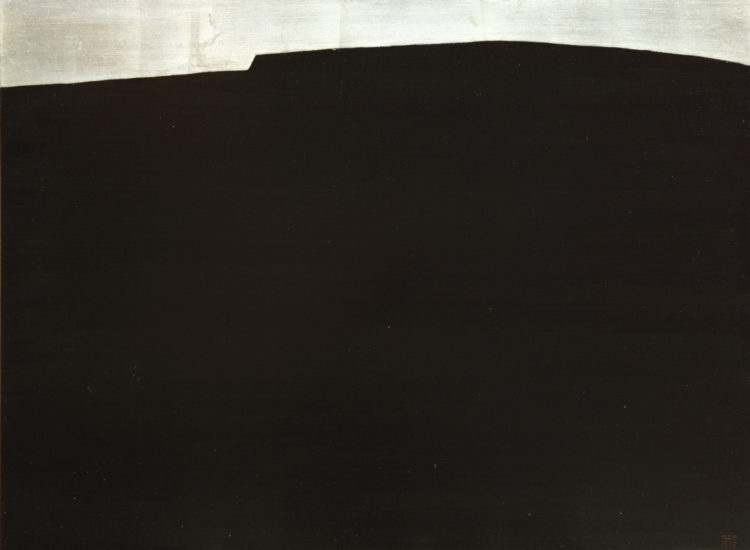

When she started painting again in 1948, encouraged by her friend the surrealist painter Bjarne Rise, she distanced herself from figuration in favour of compositions with floating shapes, reminiscent of Norwegian nature. Similar to the surrealist abstraction of the Linien group, which gave rise to the Cobra movement, her first abstract works were exhibited in Oslo in 1950 at the U.K.S. Gallery. A.-E. Bergman reconnected with Hans Hartung in 1952 in Paris, where Hans lived, now a French citizen. They remarried in 1957, never to be separated again. She worked on chisel engraving with Hans and on etching and dry point engraving with Lacourière, a master engraver. This was when A.-E. Bergman started painting her first works with gold and silver leaf, a very personal technique she would use until the late 60s. The technique consists in pasting silver, gold, or copper leaves to the canvas with a kind of tempera and varnish. The metal plating delineates a shape that catches the light and reflects it like a mirror. Most of the time, however, the metallic leaf disappears under a coat of ochre, red, or blue ultramarine, then reappears through the processes of scratching or incision. Using these noble materials, A.-E. Bergman developed a theme around a mineral world inspired by both Norwegian landscapes (stone, stele, mountain, cliff, horizon, ocean) and the figures of Norwegian mythology, such as the “draug” – a harbinger of death sailing in half a boat. Her gold and silver paintings were shown for the first time at the Ariel Gallery (Paris) in 1955. She began to gain recognition as her work was shown in multiple exhibitions in France, Europe, and the United States.

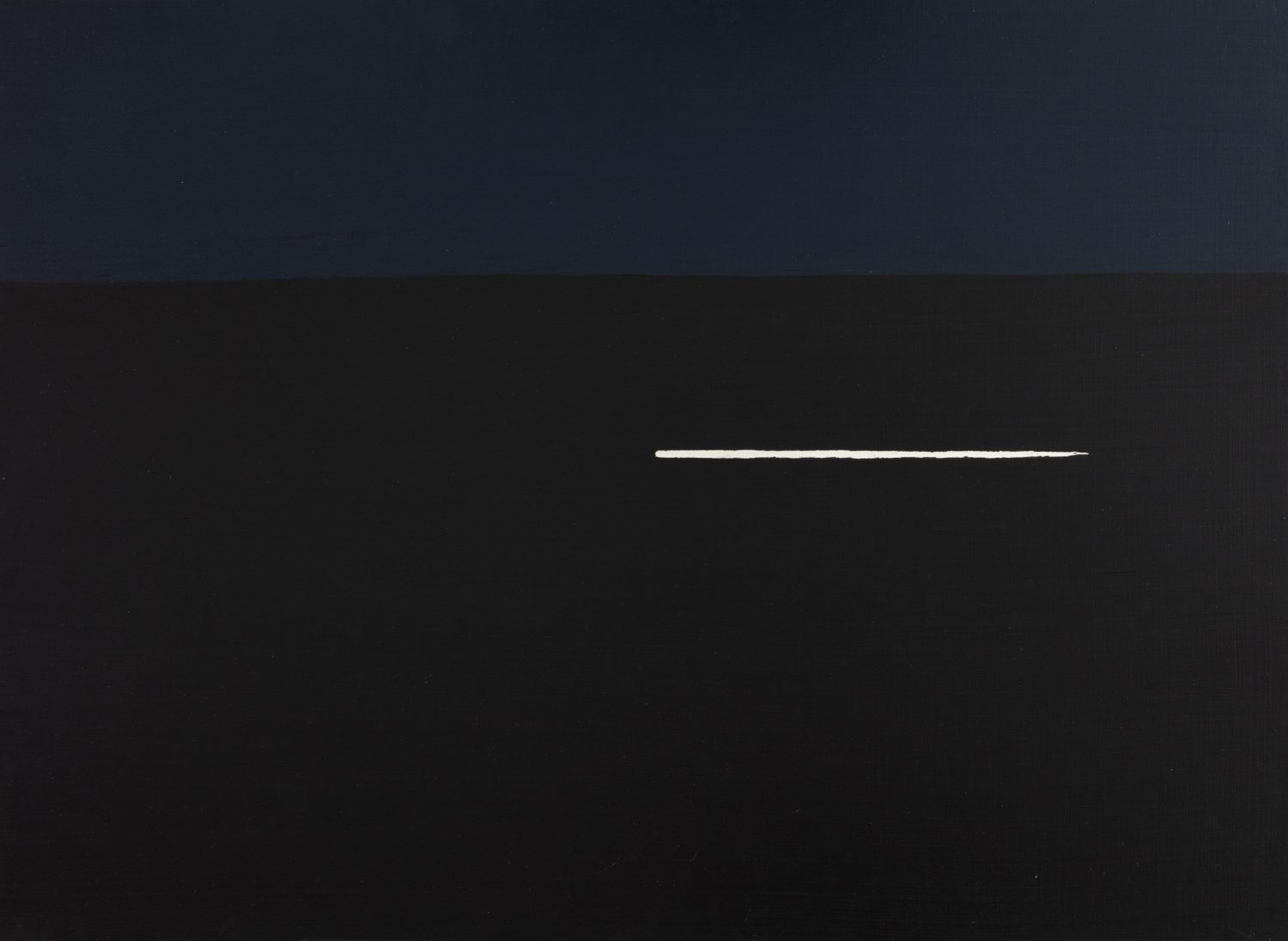

In 1973, A.-E. Bergman and Hans Hartung moved to Antibes, where she would live until the end of her life, in 1987. There, she prepared a retrospective of her work at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, inaugurated in late November 1977. In her later years, A.-E. Bergman’s style shifted towards an increasing simplification of motifs and a range of colours limited to two or three primary colours. At times, her drawing even became reduced to a single line – a line which, according to Jean Tardieu, defined a whole landscape: “In it, we see the essential form, the ‘idea’ of a mountain, of a fjord, of the horizon over sea or land, of a lake, a extraordinary tomb, an empty star, or the ‘half-boat’ they say Norwegian sailors see before they die.”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Anna-Eva Bergman, ina.fr, elles@centrepompidou

Anna-Eva Bergman, ina.fr, elles@centrepompidou