Annette Messager

Bernadac, Marie-Laure, Annette Messager. Mot pour mot : textes, écrits et entretiens, Dijon/Londres, Les Presses du réel/Violette Editions, 2006

→Duplaix, Sophie (dir.), Annette Messager, les messagers, cat. expo., Musée d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris (6 June–17 September 2007), Munich/New York, Prestel, 2007

→Grenier, Catherine (ed.), Annette Messager, Paris, Flammarion/Centre national des arts plastiques, 2012

Annette Messager. Continents noirs, Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, 13 October 2012–3 February 2013

→Annette Messager – Sous vent, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC, Paris, 2004

→Annette Messager: The Messagers, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 9 August–3 November 2008

French visual artist.

Through her father, Annette Messager discovers the old masters, religious art, as well as Dubuffet’s outsider art. This interest in folk art and crafts, in madness and childhood, will remain a constant in her work, just like the influence of Goya, Ensor, Soutine or Bacon, who often feature grotesque representations of the human condition. In 1962, she enrols in the École nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs in Paris. Her first works consist in house-shaped boxes, inspired by surrealism and Louise Nevelson. While Claes Oldenberg and his Stores are obvious influences, her use of irony specifically refers to the female figure as a social myth. She thus creates 56 scrapbook albums from the perspective of various adopted personalities: the starry-eyed girl, in Le Mariage de Mlle Annette Messager, 1971 (The Marriage of Miss Annette Messager), the practical woman in Mes travaux d’aiguille, musée de Grenoble, 1973 (My needlework). By engaging in a form of blatant auto-fiction, she deconstructs both the idea of “woman” and “artist.” In her work, the act of artistic creation is often limited to obsessive recopying or ironic embroidery, as in Ma collection de proverbes, 1974 (My collection of proverbs), an anthology of common beliefs about women.

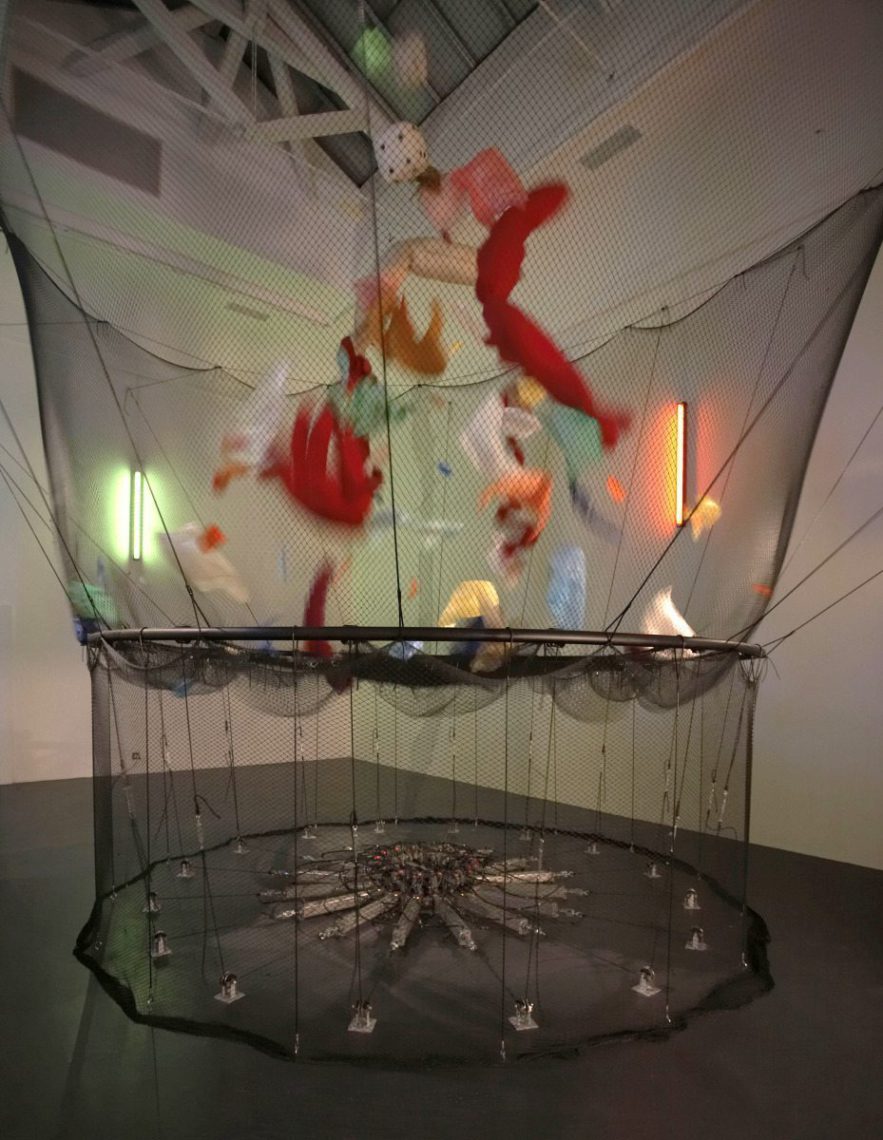

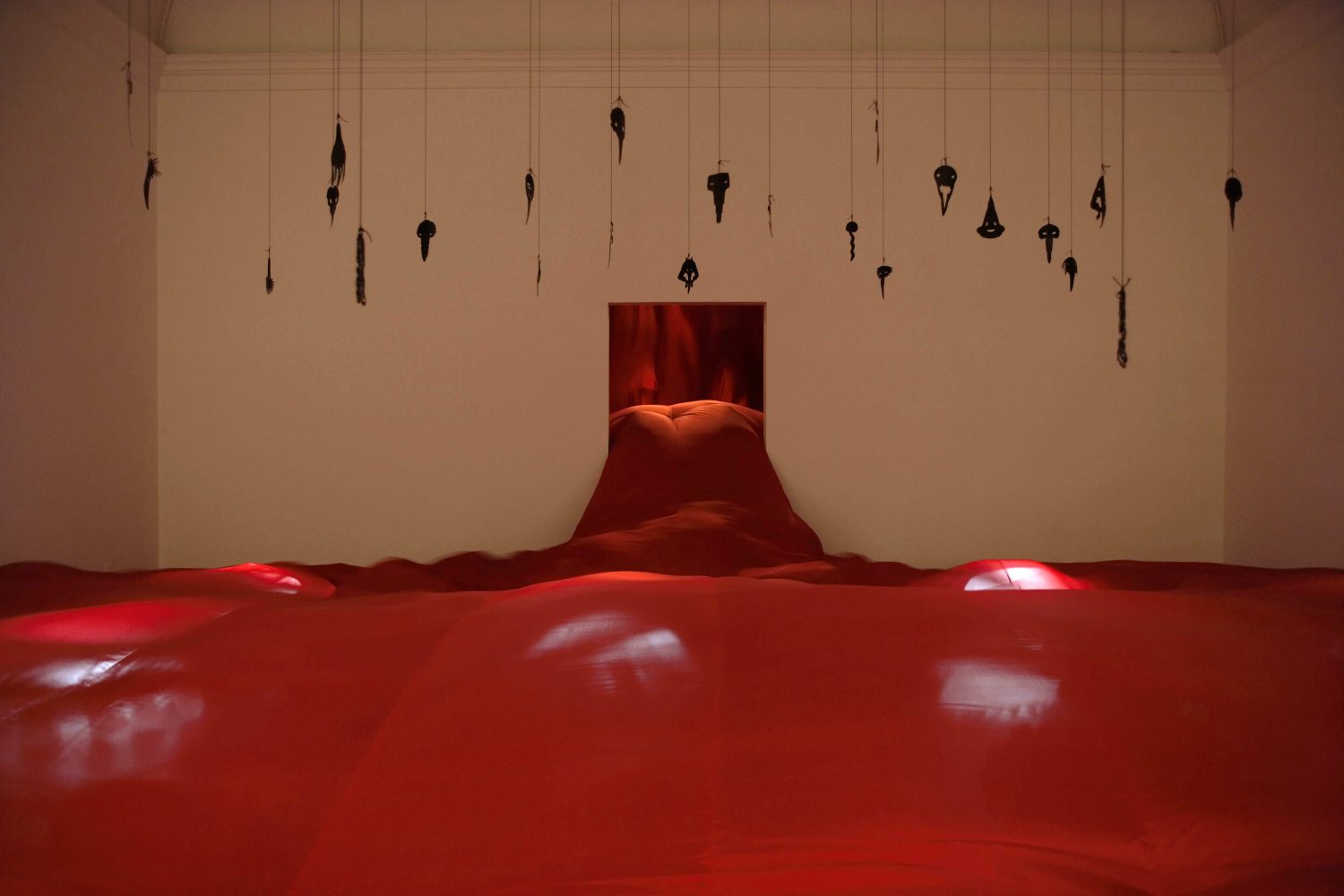

In the 1980s, the artist makes greater use of space in her work and deepens her inquiry into linguistic symbols, while making use of the two-dimensional structure of the painting. The artworks are based on photographs of body parts, enlarged then cut up, before being touched up with acrylic and oil paints for some, enhanced with charcoal, acrylic, and watercolours for others. The delicate appearance of the drawing hides the violence of this “dissection” of the human body. In 1989, the Musée de Peinture et de Sculpture de Grenoble establishes her by mounting her first retrospective. The 1990s and 2000s mark a major turning point towards sculpture and installation art. The subject of women continues to be an underlying theme in her work: the artist takes on the figure of the witch. If Histoire des robes, 1990 (Story of Dresses) seems like a lament on the anonymity of women, most of the pieces she creates during these decades subjects gloves, plush toys, and stuffed animals to violent situations, covered up by the childlike and dreamlike world they inhabit. In other creations, A. Messager integrates ambiguous beings such as lethargic bolsters and Pinocchio, the wooden puppet brought to life and dragged into strange and terrifying worlds that betray the vanity of innocence and the pervasion of good and evil in our relationship with language and the human body.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Annette Messsager's portrait

Annette Messsager's portrait  Annette Messager's Interview, 1989

Annette Messager's Interview, 1989  Interview Herstory Annette Messager

Interview Herstory Annette Messager