Research

The study of the archives of Pierre Restany (1930-2003)1 shows that the critic brought many women artists into his historiography of art, although this fact was not mentioned at the seminar dedicated to him in 2006, and this in spite of the reproduction, on the cover of the book that followed,2 of his portrait taken by Evelyne Axell for Le Joli Mois de mai (1970).

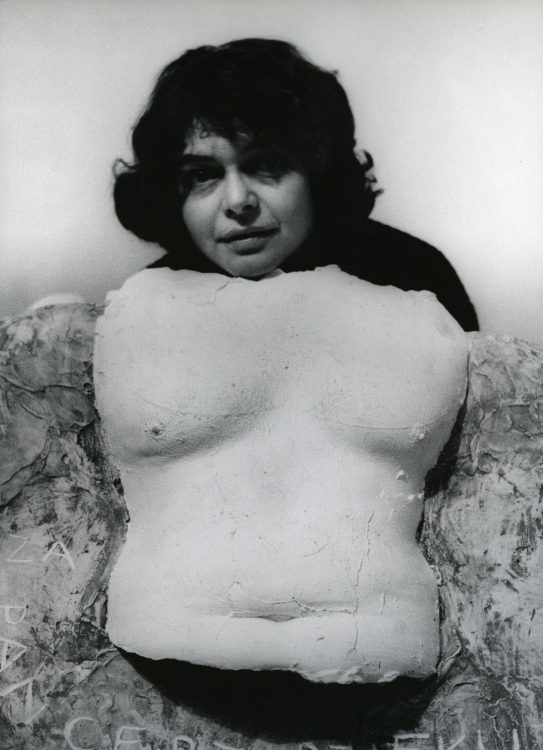

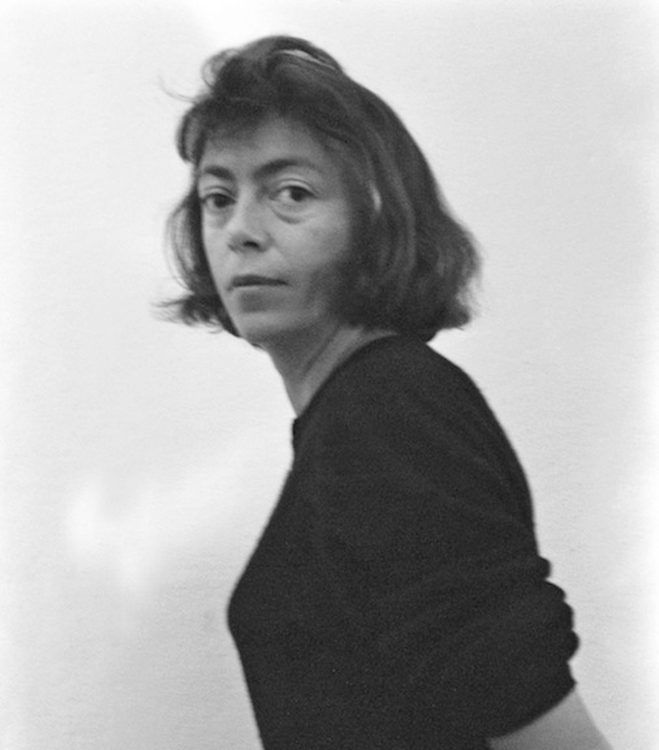

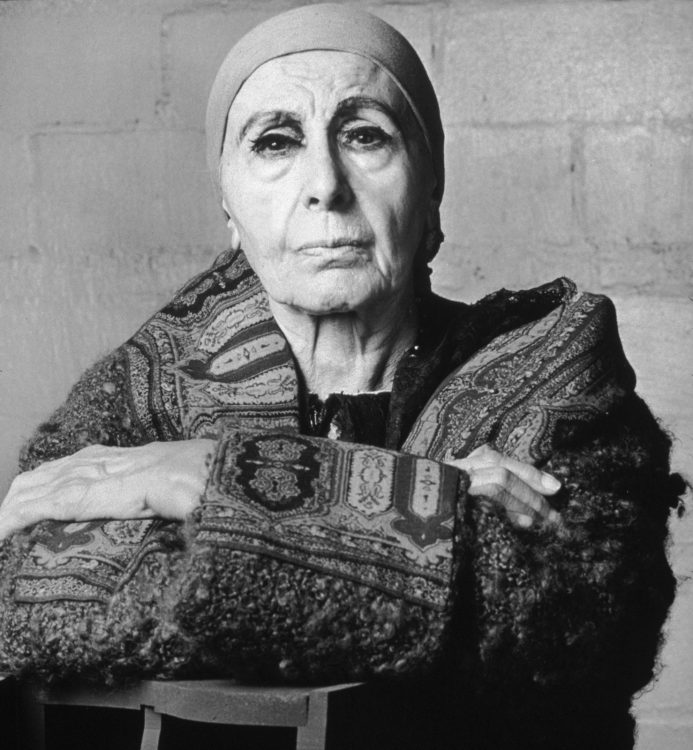

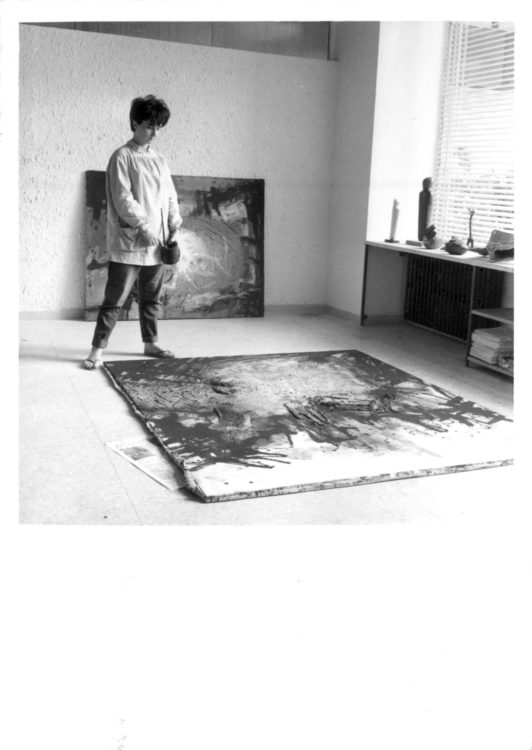

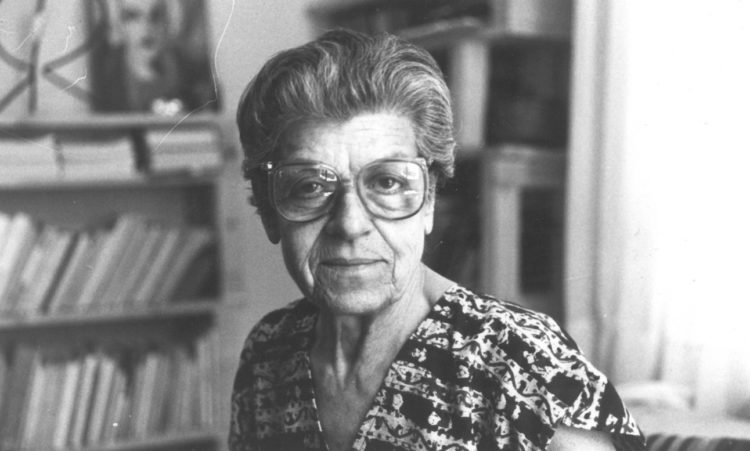

Having chosen to link his destiny to that of emerging practices, P. Restany was interested in the work of women artists on all continents. With his pen, from the immediate post-war period onwards, he had defended the work of many women artists exhibiting in Paris – Sonia Delaunay, Germaine Richier, Séraphine de Senlis – but also that of the Americans Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Louise Nevelson, and Elaine Sturtevant. However, it was the enthusiastic support that he gave to Niki de Saint Phalle, in the context of Nouveau Réalisme, which marked a shift in his career. His activism subsequently led him to support other female creators close to the Nouveau Réalisme movement, including Lourdes Castro, Nicola L., and Chryssa. As a curator, he highlighted some “feminine” approaches to art that were then considered marginal: Gina Pane, Alina Szapocznikow, Tania Mouraud, Annette Messager, and Anne Poirier (associated with Patrick Poirier), among others. He brought them together for various projects, such as the “Restany room”, exclusively dedicated to women at the Salon Grands et jeunes d’aujourdhui in 1970,3 Art Concepts from Europe at the Bonino Gallery in New York then in Buenos Aires, the World’s Fair in Japan that same year, and L’Art en position critique: pratique et théorie at the gallery of the Maison de France in Rio de Janeiro in 1974. Although he engaged with them to a lesser degree, the critic also emphasized the contributions of Catherine Ikam and Charlotte Moorman in the field of video art, Jeanne-Claude alongside Christo, and Claude alongside François-Xavier (Lalanne). The work of Juana Francés, Dorothée Selz, Greta Sauer, Carla Accardi, Esther Gentle, Eleanor Antin, Lynn Hershman, Evelyne Axell and Yayoi Kusama were also of interest to him, even though, starting in the 1980s, it is can be difficult to distinguish the writings formed of his personal convictions from those borne of financial considerations.

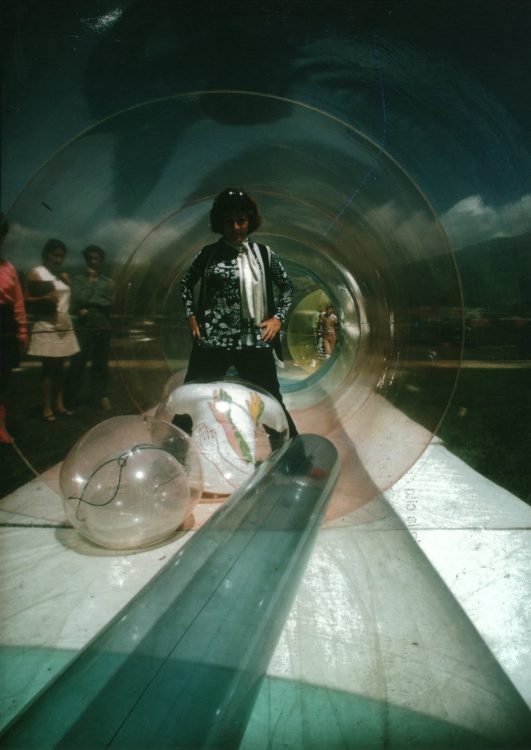

Évelyne Axell, Le Joli mois de Mai, 1970, triptych, email painted on plexiglass, 245.5 x 344.5 x 4.5 cm, © ADAGP, Paris

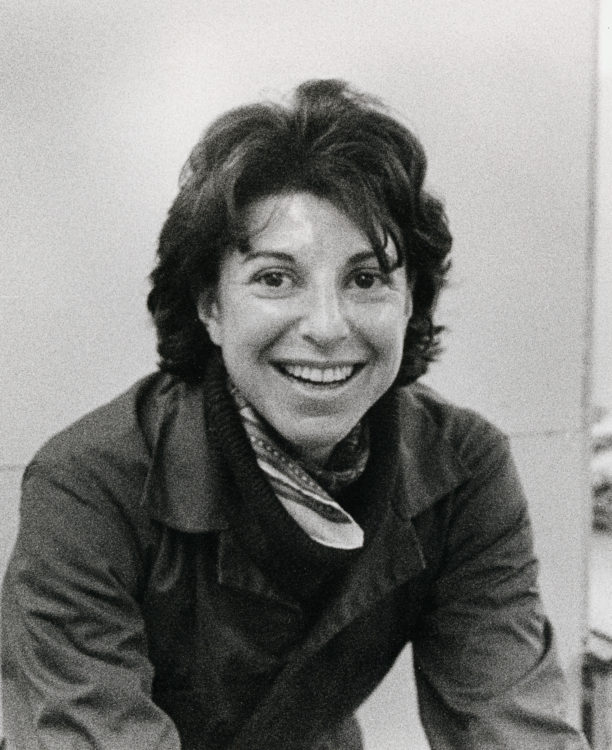

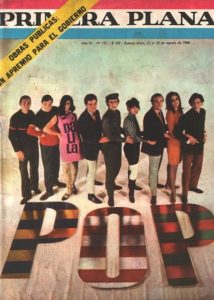

In Latin America, where he regularly travelled starting in 1961,4 P. Restany discovered an artistic ecosystem surprisingly favourable to women. Argentina interested him in particular. In spite of a tradition of segregation between men and women, Buenos Aires in the 1960s and 1970s offered women considerable visibility. Women had been inspired by and had made keen use of the image of Evita Perón, who stood out as a bold public figure. Furthermore, the absence of a solidly anchored artistic tradition rendered the weight of the patriarchy less important, and women were frequently called upon to show their work. Within the “Pop Lunfardo” movement, the South American branch of Nouveau Réalisme, P. Restany was passionate about the work of Marta Minujín. He also studied that of Marilú Marini, Delia Puzzovio, Delia Cancela, Susana Salgado, Zulema Ciordi, and Celia Barbosa. He helped introduce the work of certain Argentine artists in Parisian exhibitions (María Simon, Marta Peluffo, Margarita Paksa, and Raquel Forner). In addition, he became ardently involved with artist Lea Lublin, writing about her artworks,5 recommending her for grants,6 and organising presentations of her work.7

Cover of Primera Plana, Buenos Aires, no. 191 (23-29 August 1966). From the left to the right : Carlos Squirru, Miguel A. Rondano, Delia Puzzovio, Edgardo Giménez, Pablo Mesejean, Delia Cancela, Juan Stoppani, Susana Salgado, Alfredo Arias

His contribution to gaining recognition of artworks by women artists is, however, paradoxical: he desired not to discriminate against their production, but appreciated gender specificity. Theoretically, he defended the idea of de-conditioning the gaze, however his inextinguishable desire for the “otherness” represented by the female sex marked the limits of his conceptual commitment. This ambivalence has possibly contributed to the amnesia in the historical record regarding his actions in favour of these women artists. This omission calls into question the nature of discourse in contemporary art, and invites us to reflect on the roles of desire, discussion, and diversity in writing the history of art.

Master 2 research thesis in art history applied to the collections, directed by Sophie Duplaix and defended by Hélène Gheysens, in September 2016, at the École du Louvre.

Pierre Restany collection, held at the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA)-Archives de la critique d’art, in Rennes.

2

Richard Leeman (dir.), Le Demi-Siècle de Pierre Restany (Paris: Éditions des Cendres, INHA, 2009).

3

P. Restany wrote a text entitled “Le pouvoir féminin” [Power in the Feminine] that stipulates: “The artists who occupy the space of this room do not express themselves either more nor less ‘in the feminine’ than their male colleagues exhibited elsewhere. These modern women are specialists in the problems of contemporary visual language. Look at their works without barriers or prejudice and you will have made a little step forward in the future of your own condition.” Pierre Restany (see note 1). Text also cited in Restany Pierre, “En art, les femmes aussi”, Combat, 22 April 1974 [review of Parturier Françoise, Lettre ouverte aux femmes (Paris: Albin Michel, 1974)].

4

Isabel Plante, “Pierre Restany et l’Amérique latine. Un détournement de l’axe Paris-New York”, in Richard Leeman (dir.), Le Demi-Siècle de Pierre Restany, op. cit., 287.

5

P. Restany wrote four monographic texts on the work of Lea Lublin between 1967 and 1991. He also participated enthusiastically in one of her works, Interrogations sur l’art (1975), and cited it numerous times in historiographic articles. See Hélène Gheysens, Pierre Restany et les artistes femmes, au miroir de Lea Lublin, Master 2 thesis, under the direction of Sophie Duplaix, Paris, École du Louvre, September 2016.

6

Notably the grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which she obtained in 1984.

7

Notably with ORLAN in 1985. See Restany Pierre, “Lea, ORLAN et l’art moral”, in Lea Lublin, Michel Nuridsany, Monique Faux, Vittorio Fagone, Dominique Laporte, and Pierre Restany, ORLAN, Lea Lublin. Histoires saintes de l’art, exh. cat., (Cergy-Pontoise: Lacertidé, 1985).

Hélène Gheysens, "Pierre Restany and Women Artists." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/pierre-restany-artistes-femmes/. Accessed 7 July 2025