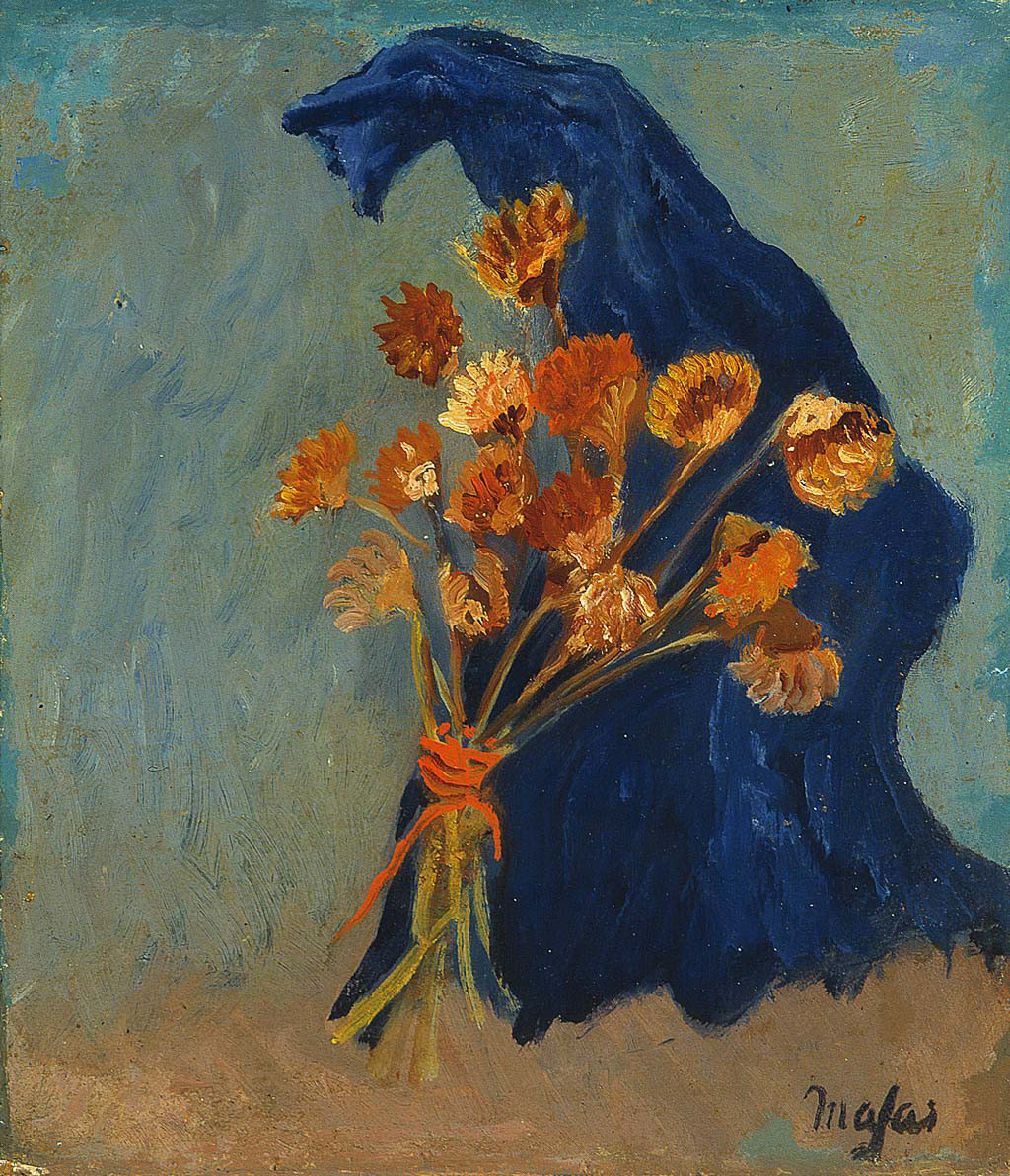

Antonietta Raphaël Mafai

Antionetta Raphaël: Materia e colore del sogno, Rome, Archivio della Scuola Romana, 2000

→Antionietta Raphaël: Sculture, dipinti, disegni, exh. cat., Galleria Ceribelli, Bergamo (25 October – 20 December 2003), Bergamo, Lubrina Editore, 2003

Antonietta Raphaël, Galleria Narciso, Roma, 1952

→Antonietta Raphaël, Sculture, Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, Milano, 1985

Lithuanian-Italian painter and sculptor.

The artwork of nomadic artist Antonietta Raphaël Mafai was marked by her travels, and it is undoubtedly because of this that she had a certain distinctiveness in the Roman scene between the 1920s and 1970s. Born in Lithuania as a result of the diaspora, she lost her father, Rabbi Simon, in 1903. At the outbreak of the first Russian revolution in 1905, she followed her mother to London. Having graduated from the Royal Academy, she also taught piano and French, and began socialising in artistic circles (with sculptors Ossip Zadkine and Jacob Epstien, and the poet Isaac Rosenberg) as well as with anarchists. After the death of her mother in 1919, she moved to Paris, where she spent time in the Montmartre of Chaïm Soutine and Marc Chagall. In 1924, she moved to Rome, where she met the painter Mario Mafai at the Accademia di belle arti the following year; he became her life partner. The couple had three daughters together, who were often Antonietta’s models. With the painter Gino Bonichi, known as Scipione, and the sculptor Marino Mazzacurati, the couple formed the Scuola di via Cavour, which later became the Scuola Romana (The Roman School), a group influenced by the lyrical and expressionist style of the Parisian school. Up until the early 1930s, A. Raphaël Mafai practiced a syncretic, poetic and exuberant painting, with hints of Byzantine and Oriental influences, in the “primitive” flavour of a colourful ingenuity recalling the experiments of the Fauves and the tonal inspirations of C. Soutine, Moïse Kisling and Marc Chagall. In 1929, she participated in a group exhibition of women, Otoo pittrici e scultrici romance, that found success amongst critics and the public.

After returning to Paris with her husband in 1930, she took evening courses in sculpture, and then went to London in 1932, where she reconnected with J. Epstein before returning to live in Rome in 1933. Although several influences emerged during this period, none, except for that of Aristide Maillol, seemed to be decisive – her style remained completely personal. A painting that debuted a longer series, Miriam che dorme (Myriam Sleeping, 1933), shows how much sculpture renewed her art. She limited herself to few subjects – her husband (whose own travels often kept them apart) and her daughters – allowing her to experiment through various portraits and expressions (slumber, singing, the face of the creator), but also group poses (Le tre sorelle [the three sisters]), as well as biblical and mythological subjects. The true subject of her work was always the nature of emotions – birth, affection, fear, fatigue, creation, death. The slow, solemn and melancholic poetry of the generous, massive, and languid bodies that she sculpted firmly planted in space, in the style of Maillol, turned away from the brilliant joy of the vivid colours of her paintings. At the beginning of the twentieth century, faces were the favoured site of experimentation in visual research. The sculptor’s delicately archaic masks – timeless, and in that sense, classic – were particularly sensitive to luminous notes and expressions born from shadows and reflections. The material – plaster, cement, wood, clay, stone and bronze – was abundantly worked, not smoothed but slashed, marked and fragmented with enthusiasm and vehemence. “The mere word ‘sculpture’ is enough to fill me with an almost religious fear.” The imprints of her thumbs, the chisel and the needle are all particularly sensitive, without hindering any of the softness of her forms.

In Rome, effervescent with sculptors – Arturo Martini, Marino Marini, Mirko, Biacomo Manzù, Pericle Fazzini – she found a place for her figures, which were at once classic and antirhetorical (as described by Fronte, the Scuola Romana’s magazine from the early 1930s). In 1939, she fled from Rome, where the racist fascist laws prohibited her from exhibiting her work. After several years in Genoa, she finally was recognised after the war at the Rome Quadrennial, the Venice Biennial, as well as several solo exhibitions. Her subjects became more biblical and Ovidian. She nourished her art– sculptures, drawings, lithographs, and painting once again starting from the 1960s– with her travels in Sicily, Andalusia and China. The Journal that she left behind pleasantly teaches us more about her techniques as well as about her free and whimsical imagination, the life source for her works.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019