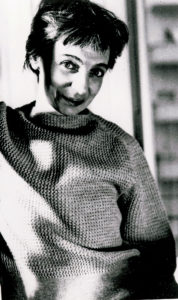

Bice Lazzari

Scotton Flavia, Miracco Renato, Crispolti Enrico, Bice Lazzari: l’emozione astratta [Bice Lazzari : abstract emotion], exh. cat., Galleria intrenazionale d’arte moderna Ca’Pesaro, Venice [August – September 2005], Edizioni Mazzotta, Venice, 2005

→Cortesini Sergio, Bice Lazzari, l’arte misura : ritratto di una pittrice tra Venezia e Roma [Bice Lazzari: art as a measure: portrait of a painter between Venice and Rome], Rome, Gangemi editore, 2002

→Montana Guido, Bice Lazzari : moderna, Galleria Civica, Modena, 1980

Bice Lazzari : la poetica del segno, Museo Novecento, Florence, October 2019 – Feebruary 2020

→Bice Lazzari, Sotheby’s, London, February – March 2018

→Bice Lazzari, l’equilibrio dello spazio, Museo d’arte contemporanea Roma, Rome, June – October 2011

Italian painter.

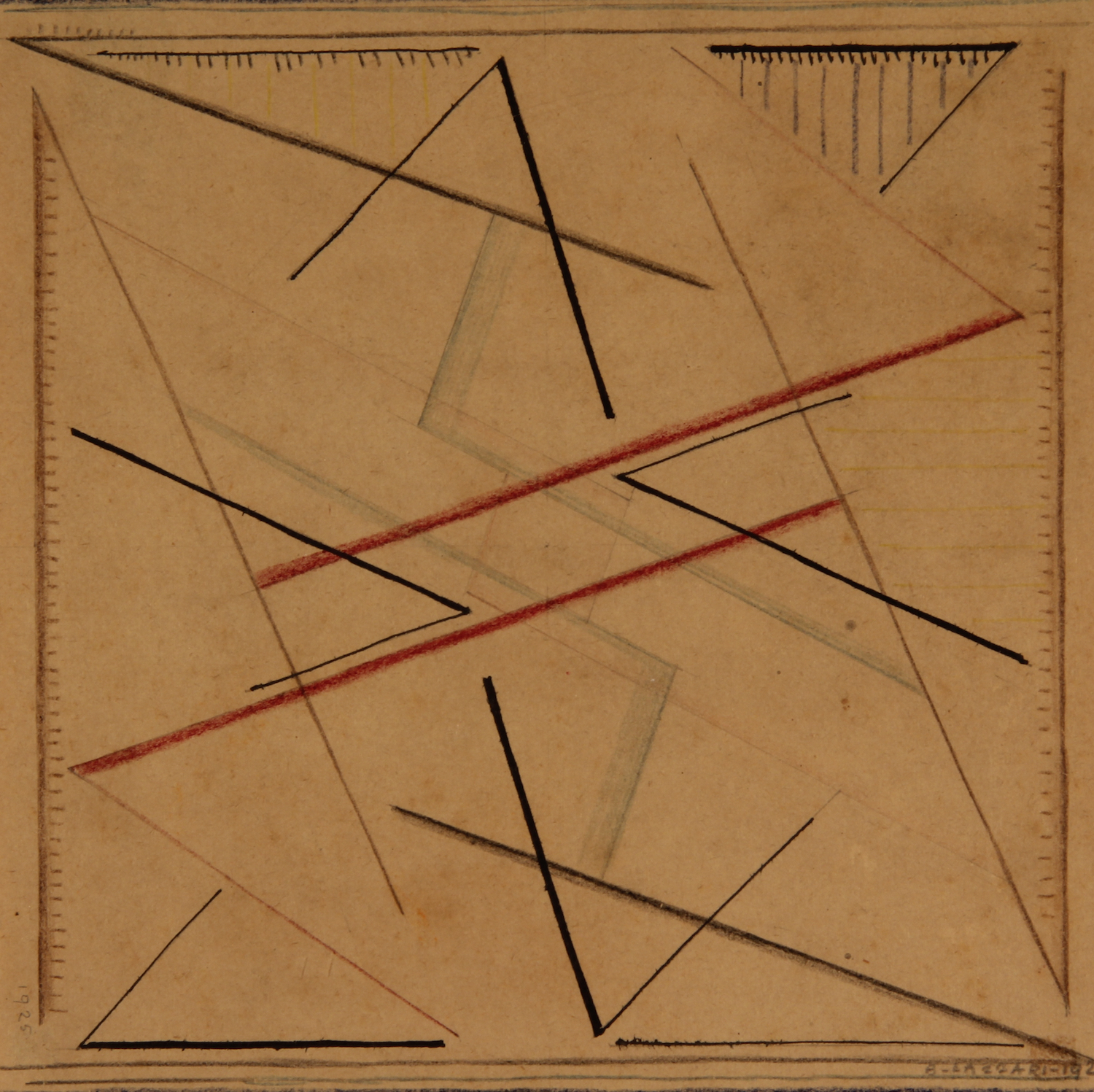

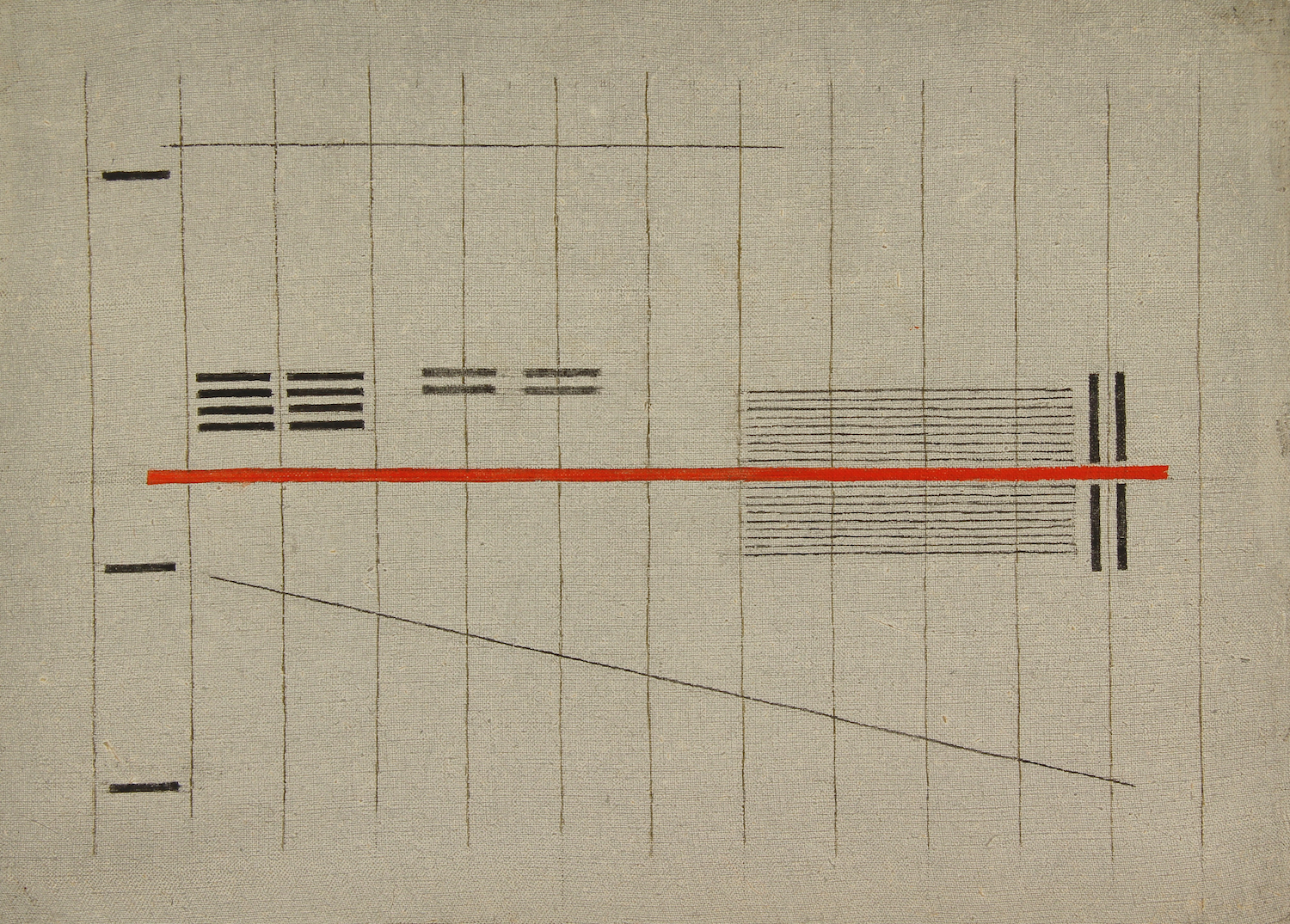

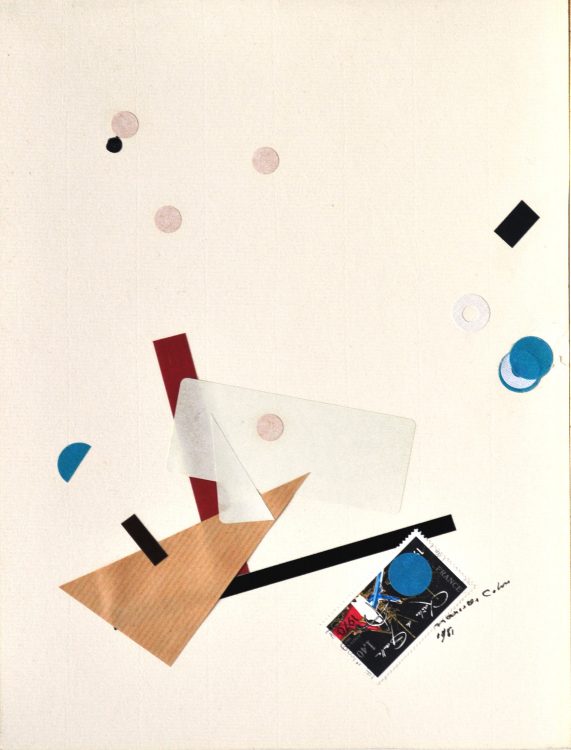

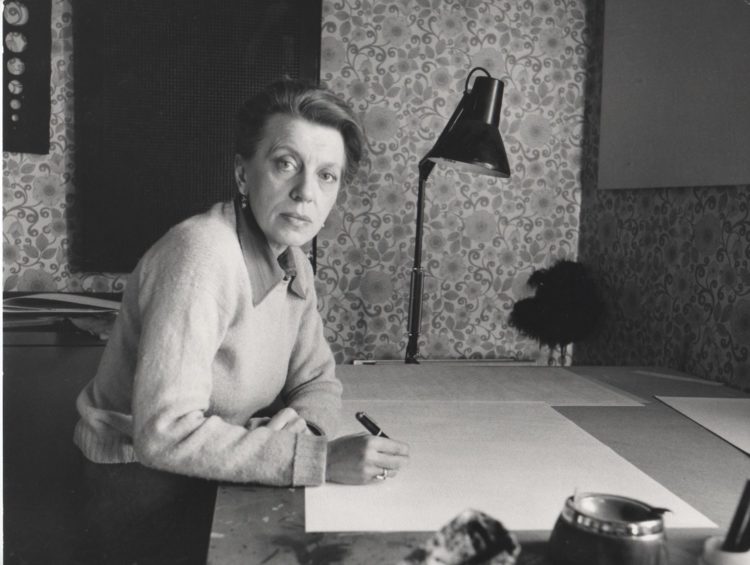

An isolated and solitary figure, Bice Lazzari came from a good bourgeois Venetian family of entrepreneurs and architects. In 1916, she enrolled at the Venice Academy of Arts, where she decided to take courses in design rather than painting, which was regarded as unseemly for a ‘young lady from a good family’ because the classes involved working from the nude. From 1925 on, she focused on the applied arts, which at the time was one of the few professions open to a young woman artist who wanted to be able to live from her work rather than depend economically on a husband. ‘It is only by our efforts that tomorrow we will leave our mark on the passage of time’,1 she once said. The field of applied arts, full of innovation and open to stylistic experiment, gave her the freedom to study and apply the non-figurative trends in the modern decorative arts. Until the late Rome 1930s, Lazzari did not regard abstraction as an intellectual option or consciously plan to break with tradition; instead, she saw it as the determinedly avant-garde product of a modern and functional style (Italy) of interior design, sophisticated but always ornamental.

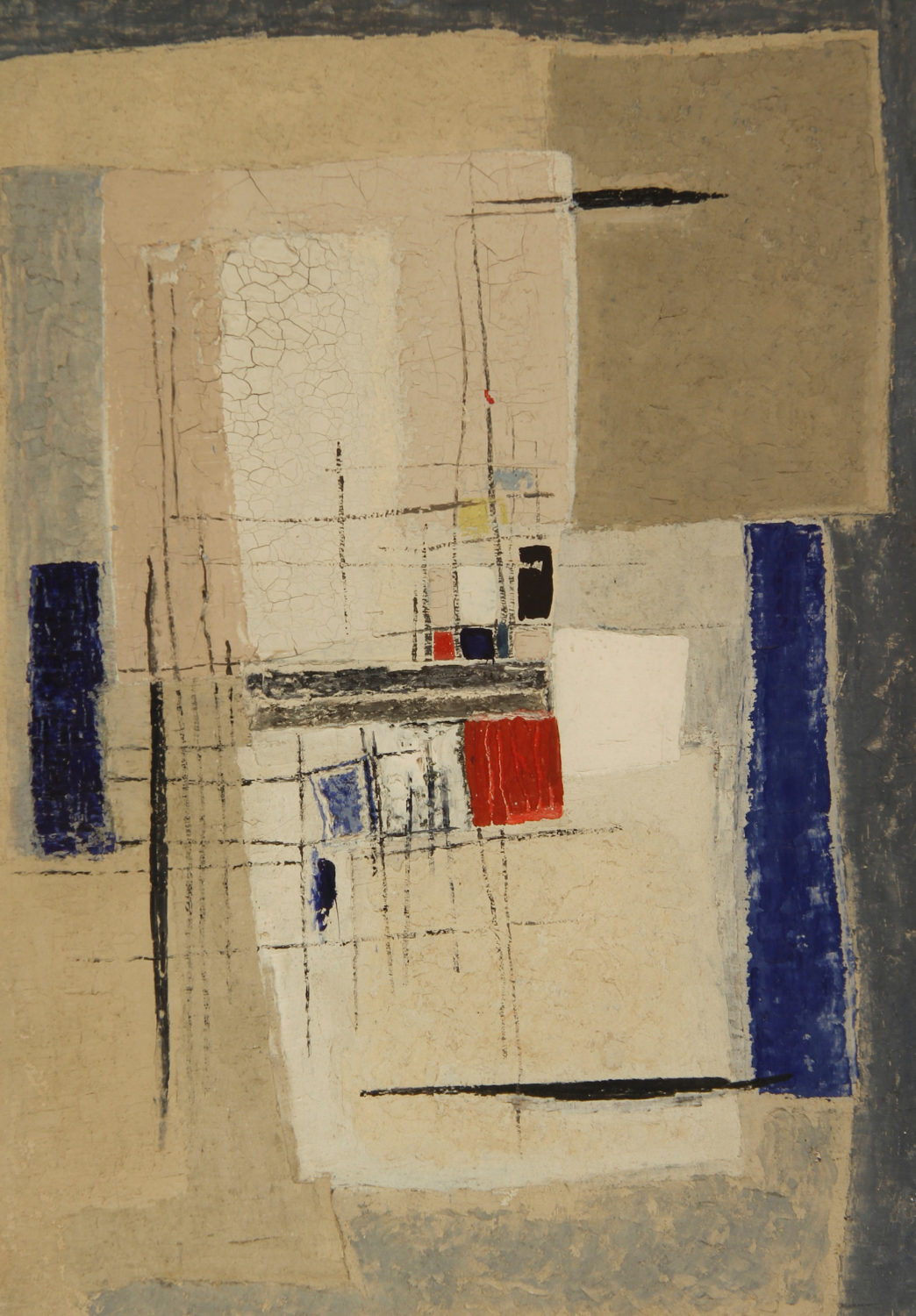

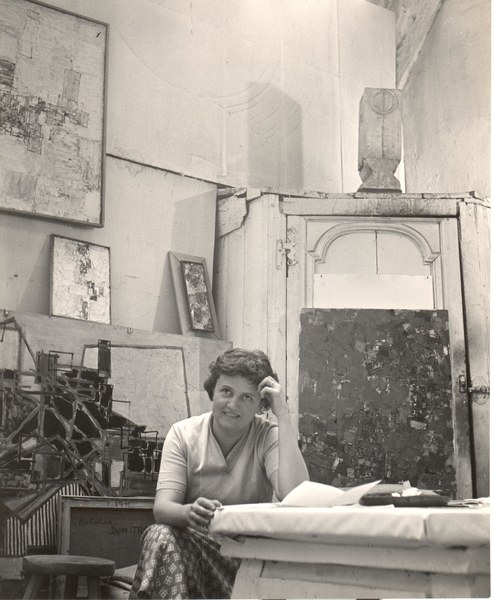

In 1935, Lazzari moved to Rome, where she continued her fruitful collaboration with the greatest architects and designers of the time. It was not until after the Second World War, in 1949, that she concentrated once again on painting, out of personal choice rather than on commission. Her works from the 1950s are ‘one of the most precious examples of Italian informal painting’.

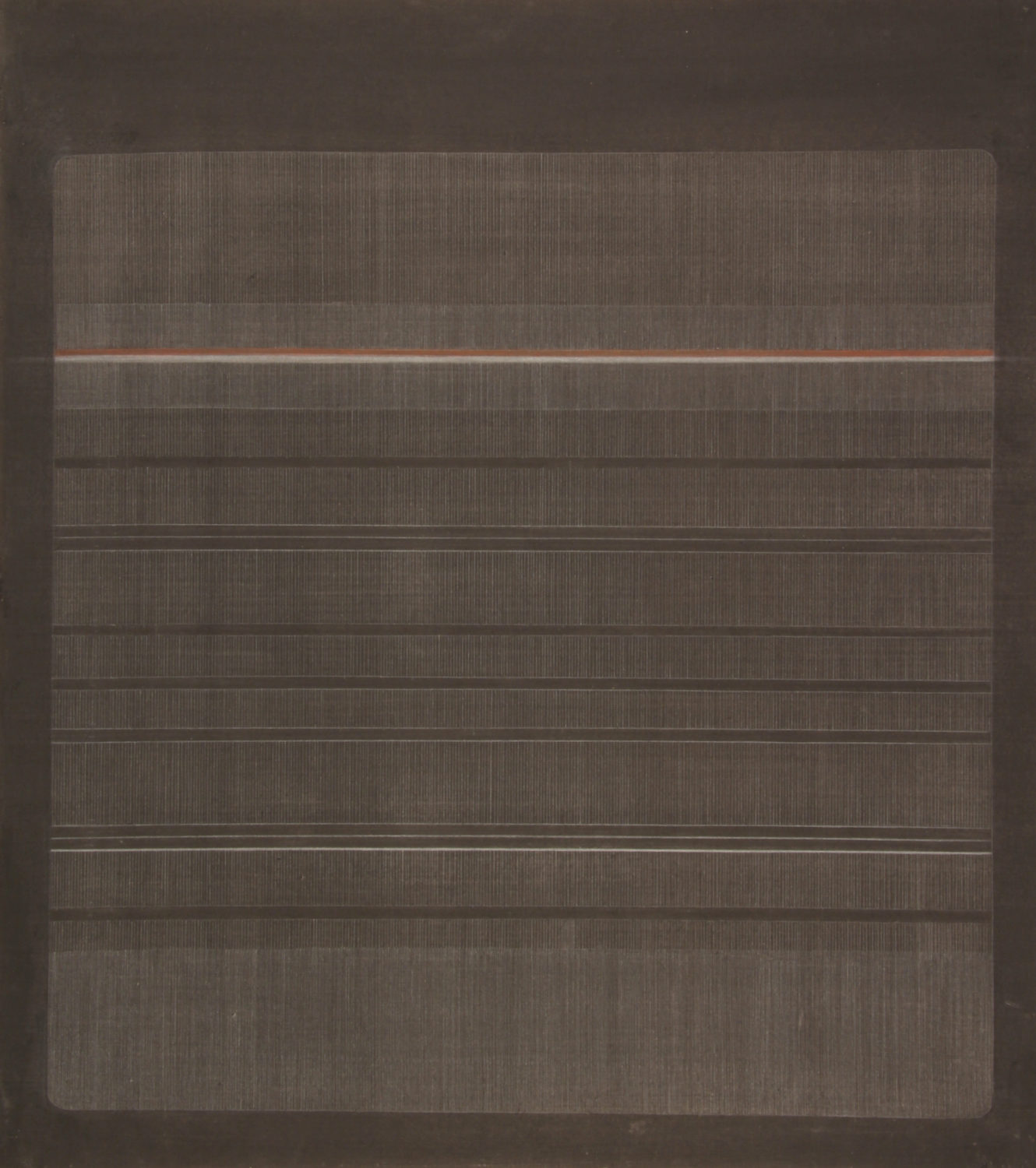

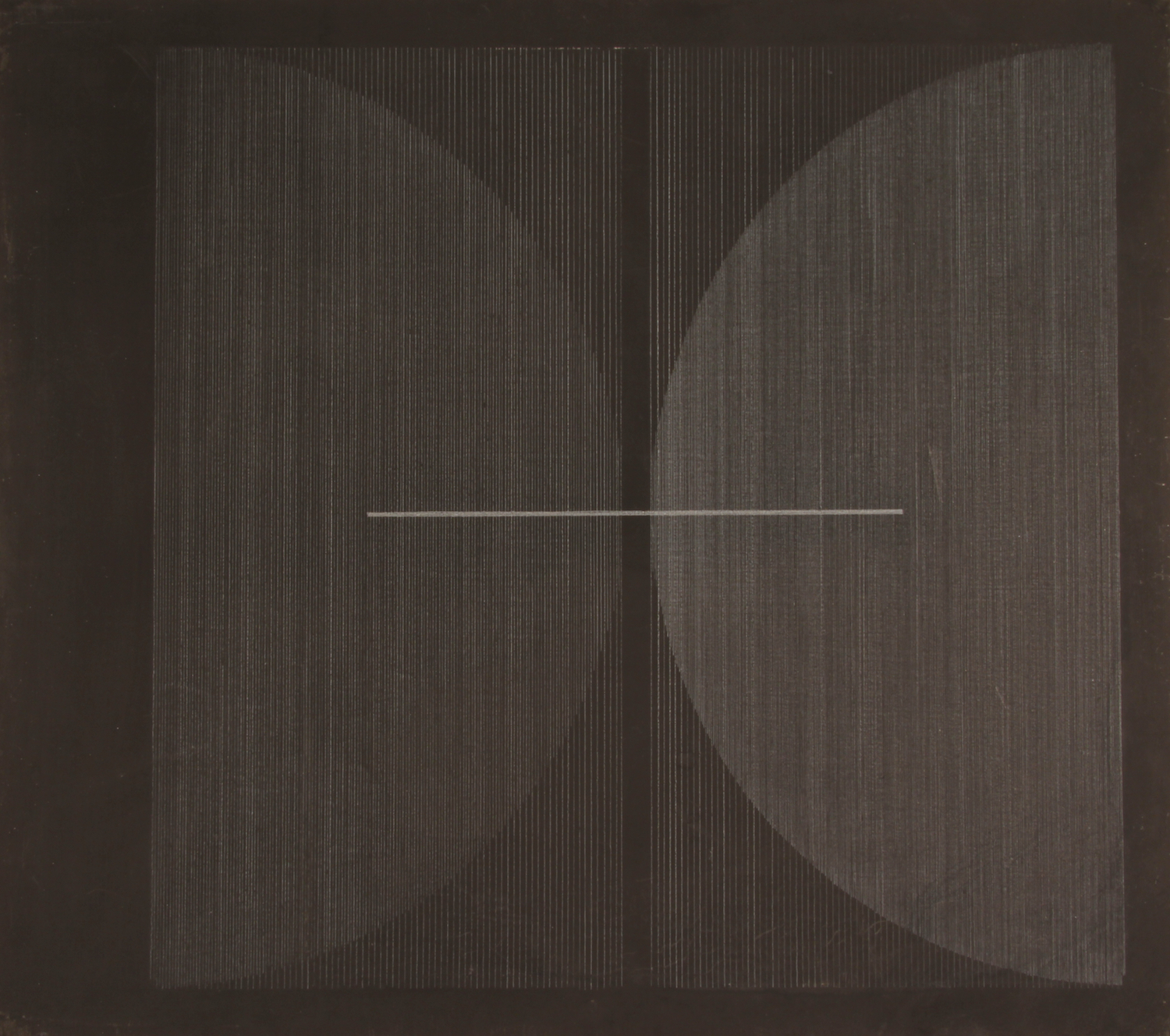

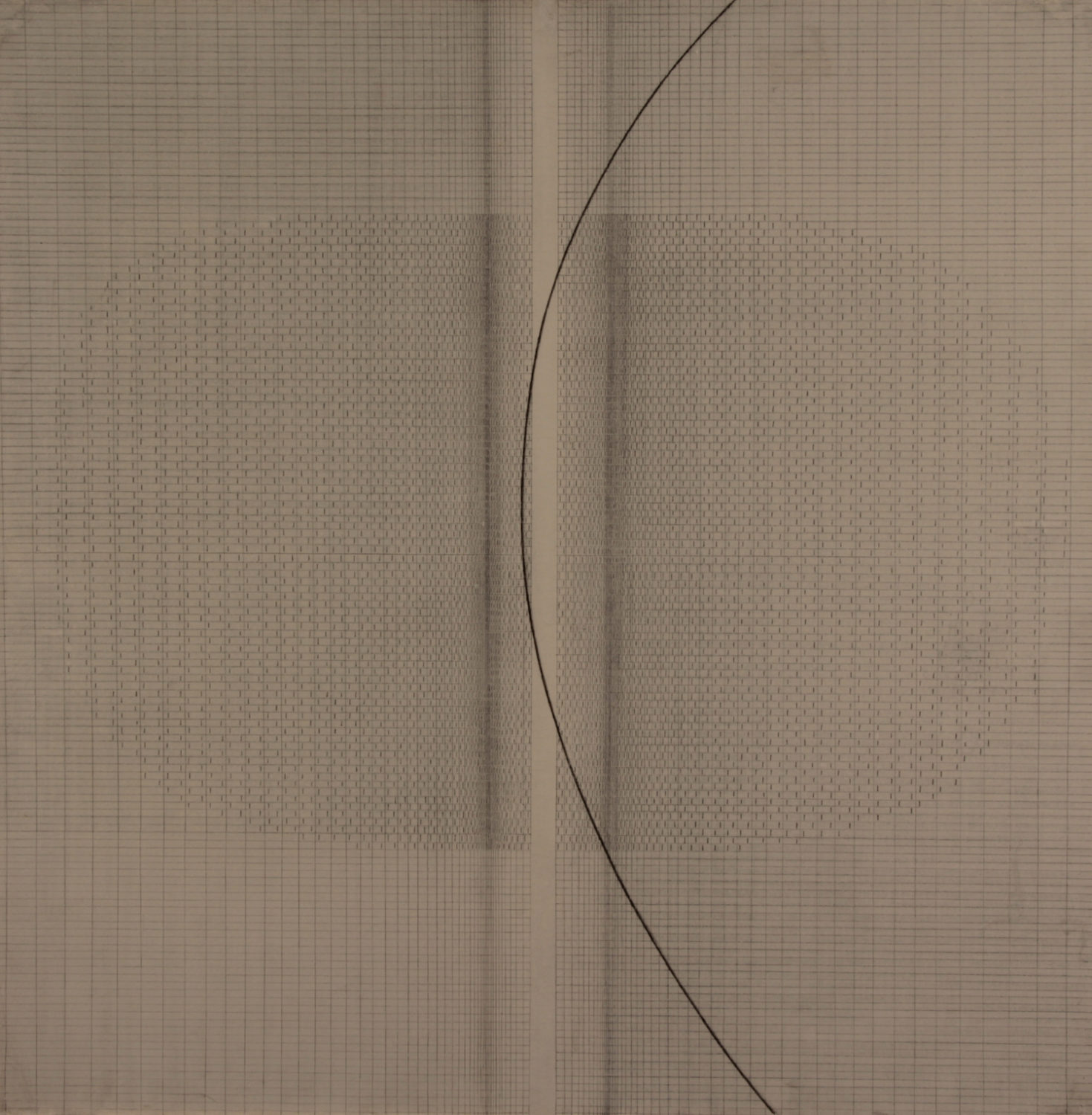

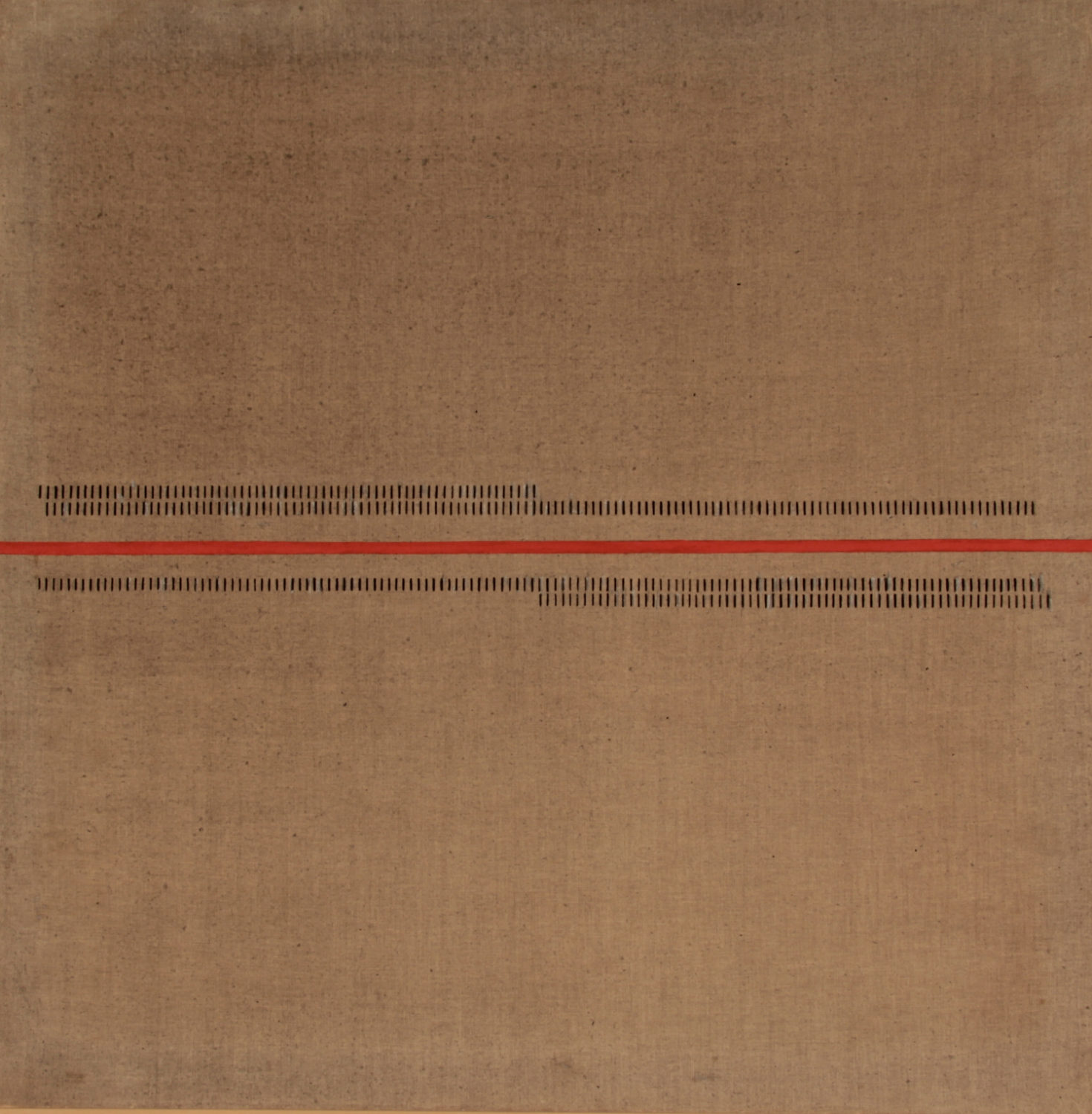

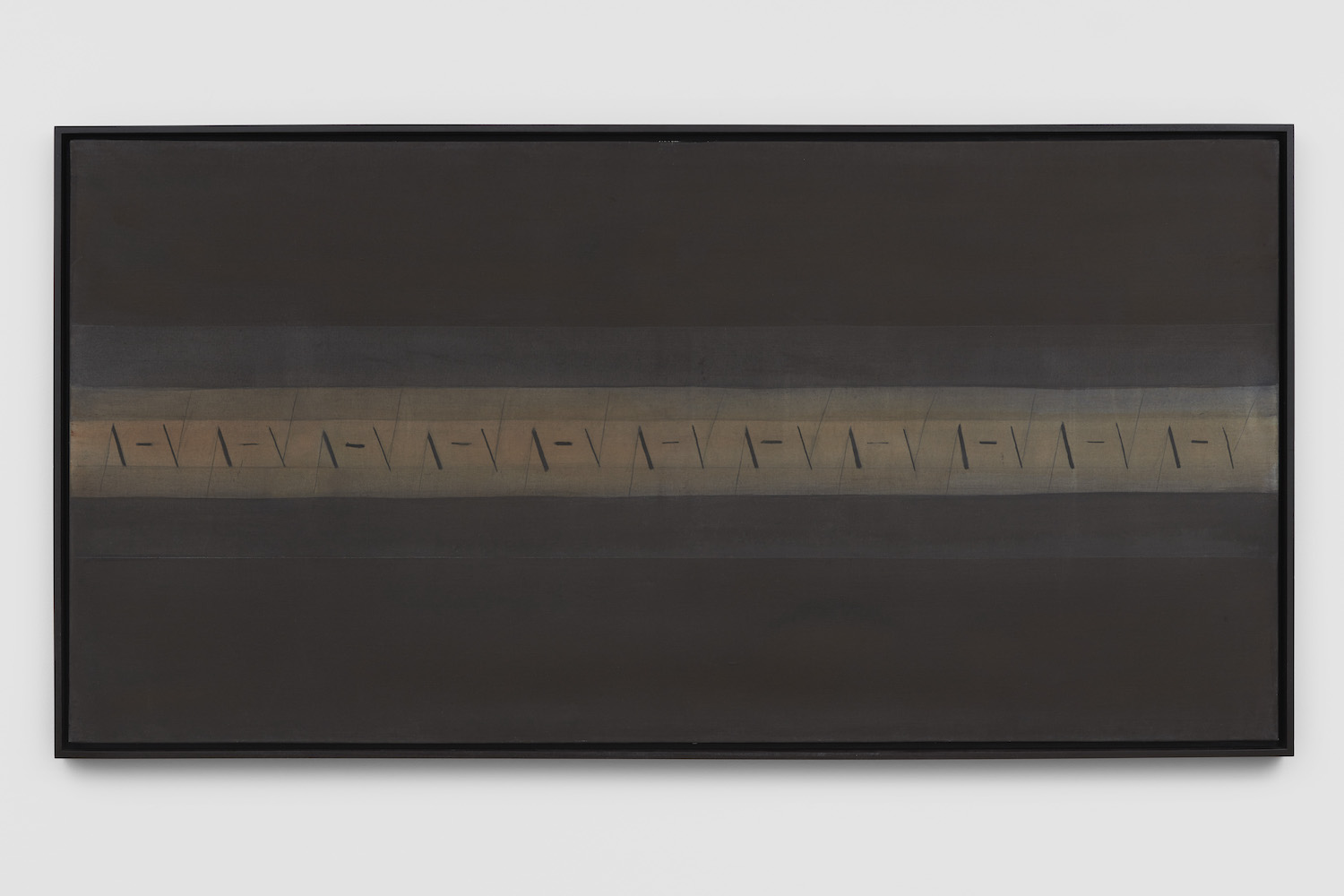

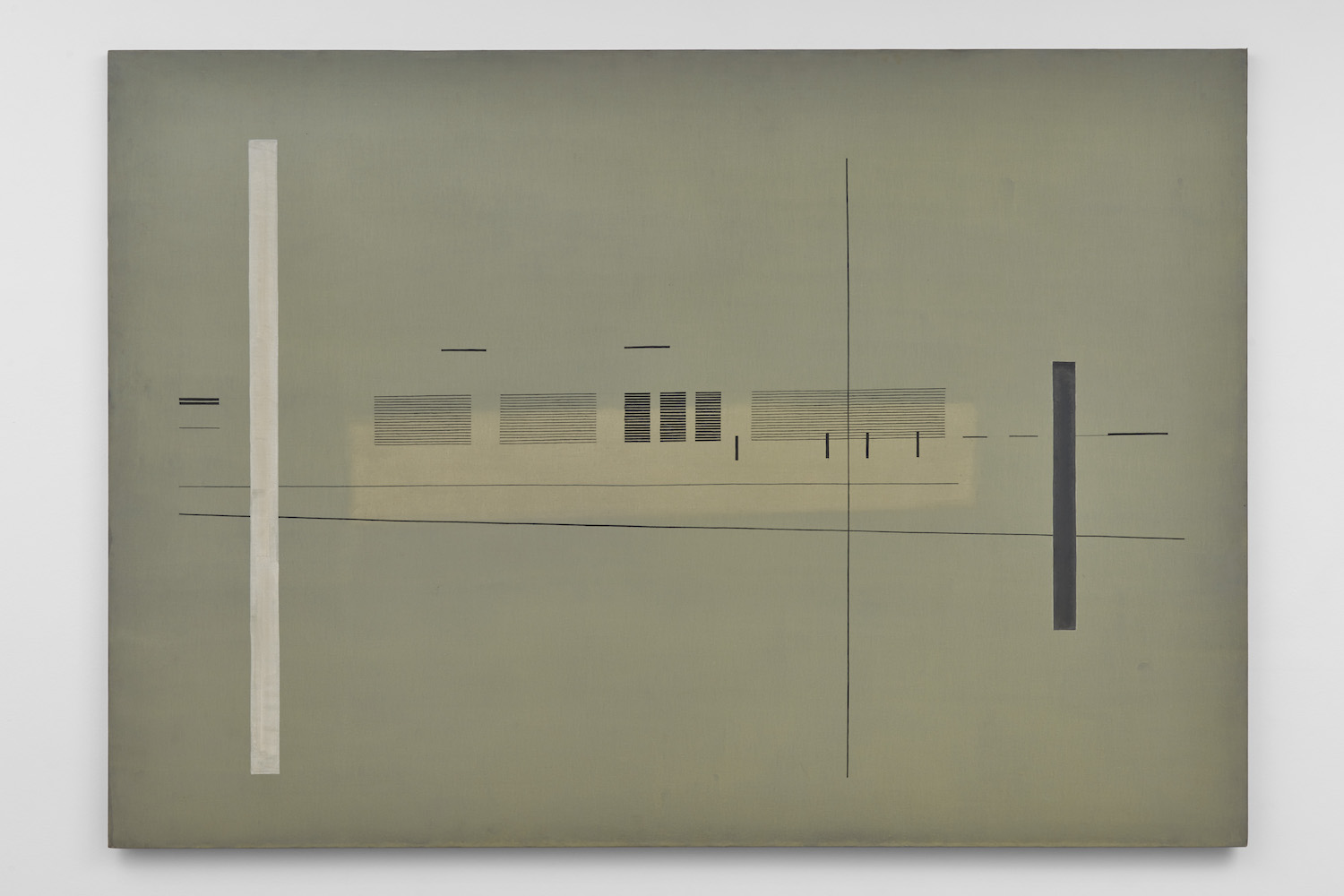

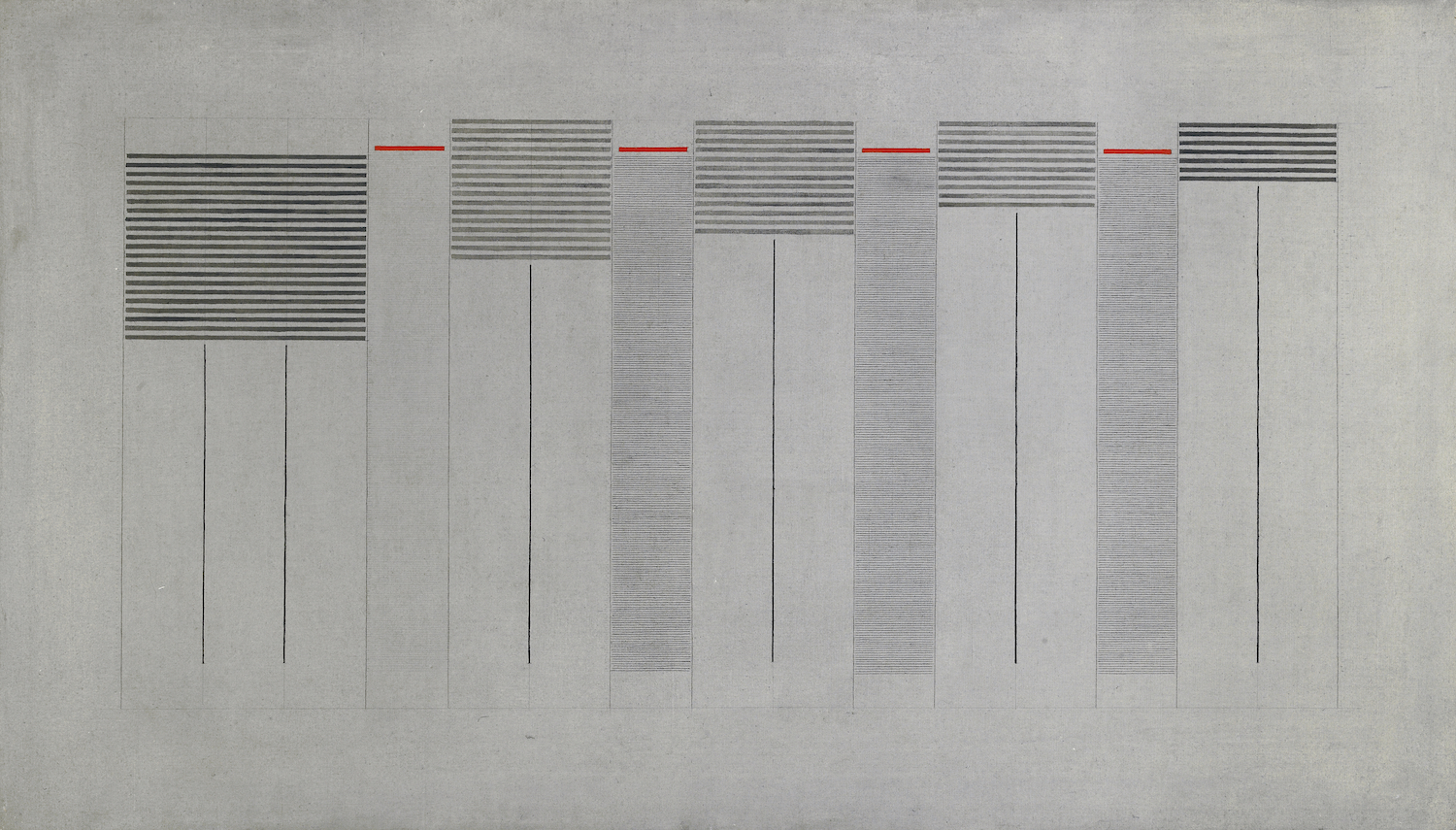

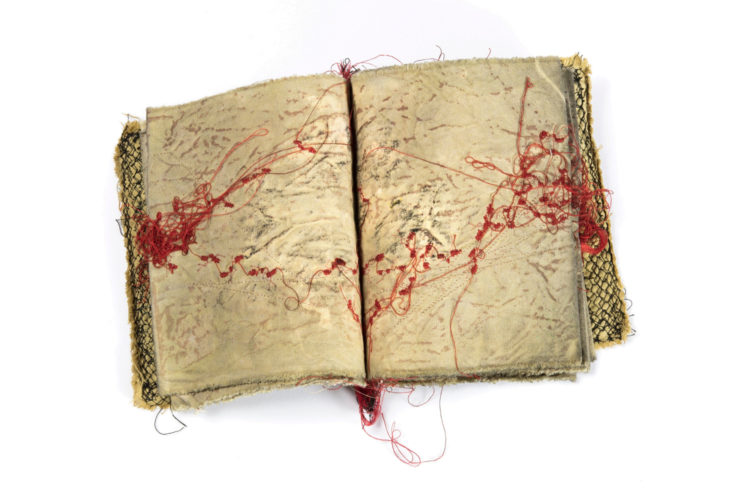

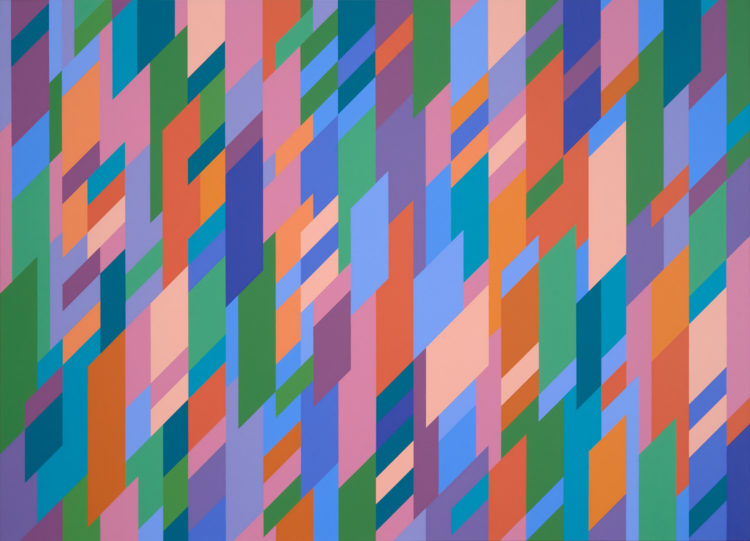

After 1959, Lazzari’s paintings became completely materialist with her use of new materials such as glue, sand, and gouache. Nero e viola (Black and violet) is an excellent example of this happy period, a work in which the artist combines the lightness of the marks with the thick consistency of the gouache that she applied directly to the canvas with a palette knife. In 1970–1, she changed her pictorial register entirely and turned exclusively to acrylics, because they were more fluid and brighter. The most successful abstract paintings that she produced as a result of her research since the mid-1920s date from that last decade. Here the sign is repeated in obsessive and rhythmic fashion on the monochrome canvas, and the composition, despite its pared-back geometric simplicity, still sounds a unique and original note of lyricism. These works from her mature period have an impeccable formal balance, in which the sign rhythmically articulates the space of the canvas, drawing the viewer’s eye to the perfect equation she creates between space, time, and scale.

As published in Women in Abstraction © 2021 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London