Carrie Mae Weems

Lewis, Sarah E. (ed), Carrie Mae Weems, Cambridge, The MIT Press, 2021

→Delmez, Kathryn E (ed), Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2012

→Patterson, Vivian (ed), Carrie Mae Weems: The Hampton Project, New York, Aperture, 2000

Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video, Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, September 2012–January 2013

Traveled to: Portland Art Museum, Portland, February–May 2013; Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, June–September 2013; Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University, Stanford, October 2013–January 2014; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, January–May 2014

Carrie Mae Weems: The Hampton Project, Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, March–October 2000

Traveled to: International Center of Photography, New York, January–April 2001; The High Museum of Art, Folk Art and Photography Galleries, Atlanta, June–September 2001; The University Museum, California State University Long Beach, Long Beach, January–April 2002; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, October 2001–January 2002; The Hood Museum, Dartmouth College, Hanover, September–December 2002

Carrie Mae Weems, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, January–March 1993

Traveled to: The Forum, St. Louis, April–May 1993; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, June–August 1993; Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, August–November 1993; California Afro-American Museum, Los Angeles, December 1993–February 1994; Portland Art Museum, Portland, March–May 1994; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, July–October 1994; The Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia, October 1994–January 1995; Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, February–April 1995

American photographer and conceptual artist.

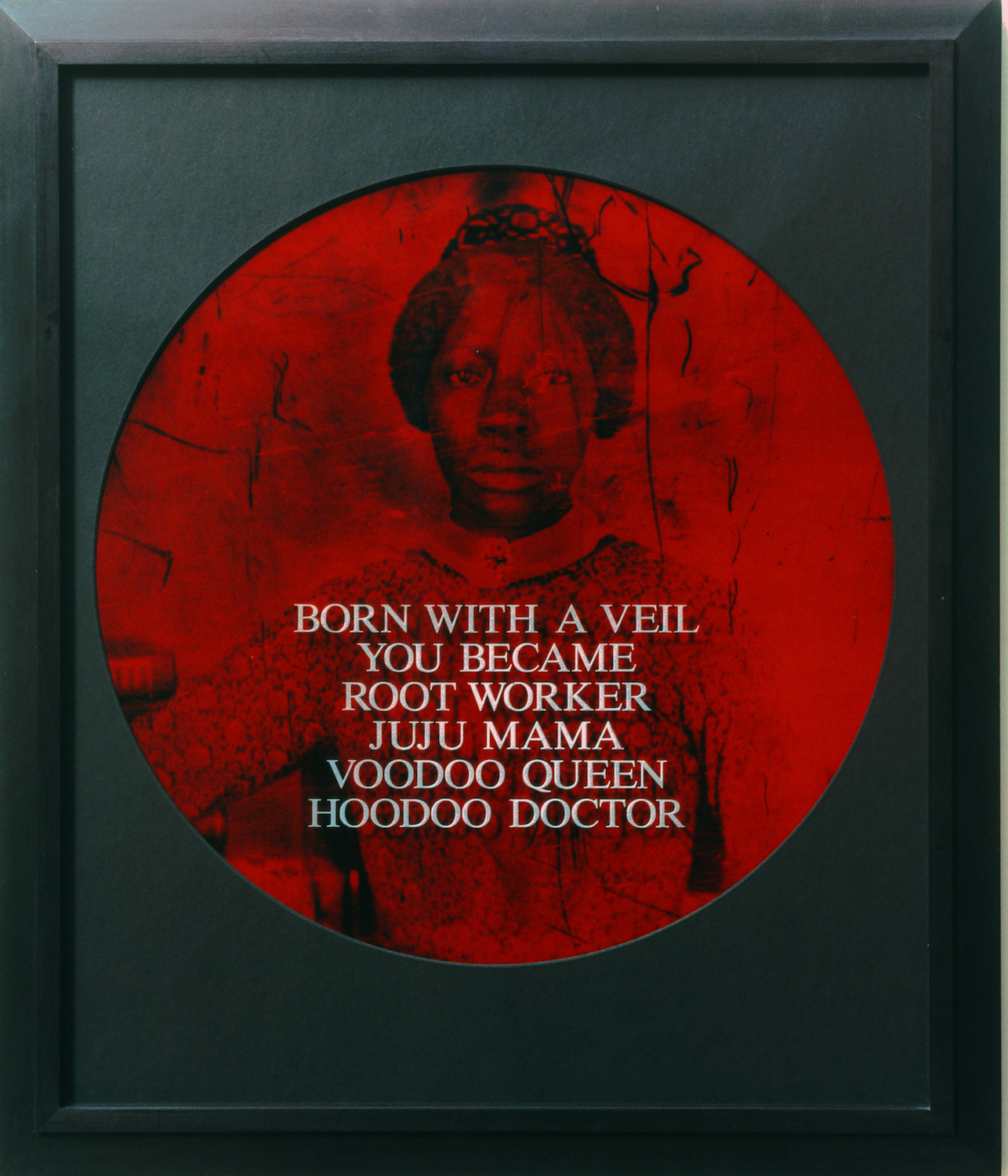

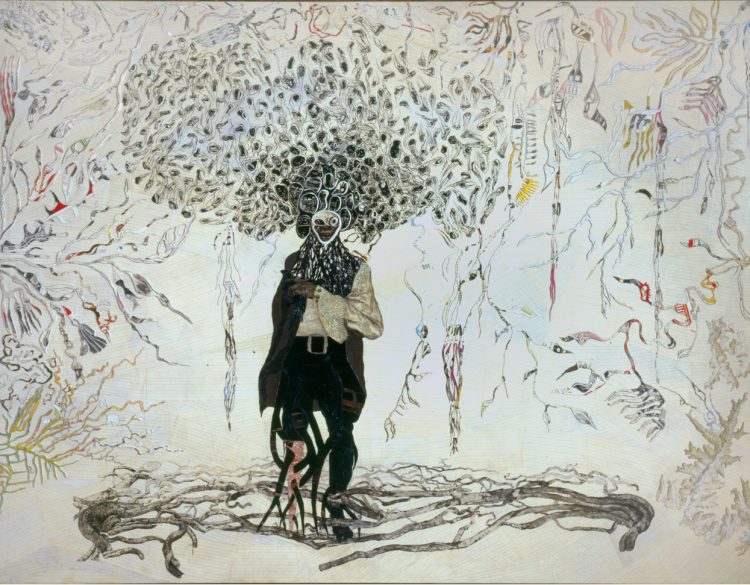

Photographer Carrie Mae Weems graduated from the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, in 1981 with a BFA degree and from the University of California, San Diego in 1984 with an MFA degree. C. M. Weems’s conceptual photography often makes use of techniques such as photo-text installation, appropriation, seriality and an emphasis on language. She emerged as a force in the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s, alongside contemporary conceptual photographers Lorna Simpson and Glenn Ligon. C. M. Weems built on, but dramatically complicated, the white feminist critique of representations of women by slightly older postmodern photographers such as Cindy Sherman, Sarah Charlesworth and Sherrie Levine by insisting on emphasising the “constructedness” of race in representation as well as the systematic elision of Black women’s bodies from fine art images and the work of Black women artists from art discourse and institutions. C. M. Weems’s practice, alongside the work and writing of Adrian Piper and Lorraine O’Grady, marks a major intervention into the period’s feminist theorisations of representation.

C. M. Weems works in serialised groups of photographs. In one of her earliest series, Ain’t Jokin’ (1987-1988), she combined black-and-white images with text in biting social critiques that are also intersectional examinations of gender and race. In Mirror, Mirror (1987-1988), for example, C. M. Weems photographs a black woman looking into a mirror. The final image includes a text below, which reads: “Looking into the mirror, the Black woman asked, ‘mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the finest of them all?’ The mirror says, ‘Snow White, you Black bitch, and don’t you forget it!!!’” While period feminist discussions of the male gaze often tacitly elided issues of whiteness, C. M. Weems forces us to contend with the ways in which vision also constructed race. In the late 1980s simply imaging the Black female body was a confrontation. Frequently photographing herself in the guise of various personas, C. M. Weems is both photographer and subject, doubling the threat by asserting her authorship.

The Kitchen Table Series from 1990 launched C. M. Weems’s career and remains her most well-known body of work. A group of more than twenty photos and text panels, the vignettes in the series depict various members of a community living their lives around a kitchen table as part of a narrative that follows the rise and fall of a romantic relationship, in which C. M. Weems photographs herself as the protagonist. The series builds on C. M. Weems’s commitment to imaging Black women’s experiences and also reflects generally on romantic partnership, monogamy, parenthood and gender roles in the family. In the work Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Makeup) (1990), a mother and young daughter sit at the table applying lipstick, raising questions about the construction of femininity in relation to the family. C. M. Weems insists that viewers not understand her work solely as an expression or documentation of Blackness, even as she images the specificity of her own experience.

In her projects of the last 30 years, C. M. Weems has appropriated and redeployed historical images of Black bodies and continued to use herself as a “muse” persona who has visited various sites of historical trauma including antebellum Louisiana and the exteriors of major European museums.

C. M. Weems has had a major traveling solo exhibition in every decade of her career, and she was the first Black woman to receive a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (2014). Her work is held in more than fifty major international collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Tate Modern, London and the Ludwig Museum, Cologne. She has received numerous awards and grants, including the MacArthur “Genius” grant and the Prix de Rome.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022