Catherine Opie

Molesworth Helen (ed.), Catherine Opie: Empty and Full, Berlin, Hatje Hantz, 2011

→Myles Eileen, Catherine Opie : Inauguration, New York, Gregory R. Miller and Co., 2011

→Bresciani Ana Maria, Hansen Tone (ed.), Catherine Opie : Keeping an Eye on the World, exh. cat., Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, Høvikodden (2017), Cologne, Walther König, 2017

Catherine Opie : American Photographer, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 26 September – 7 January 2009

→Catherine Opie: Figure and Landscape, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 25 July – 17 October 2010

→Catherine Opie : 700 Nimes Road, MOCA Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles, 23 January – 8 May 2016

American photographer.

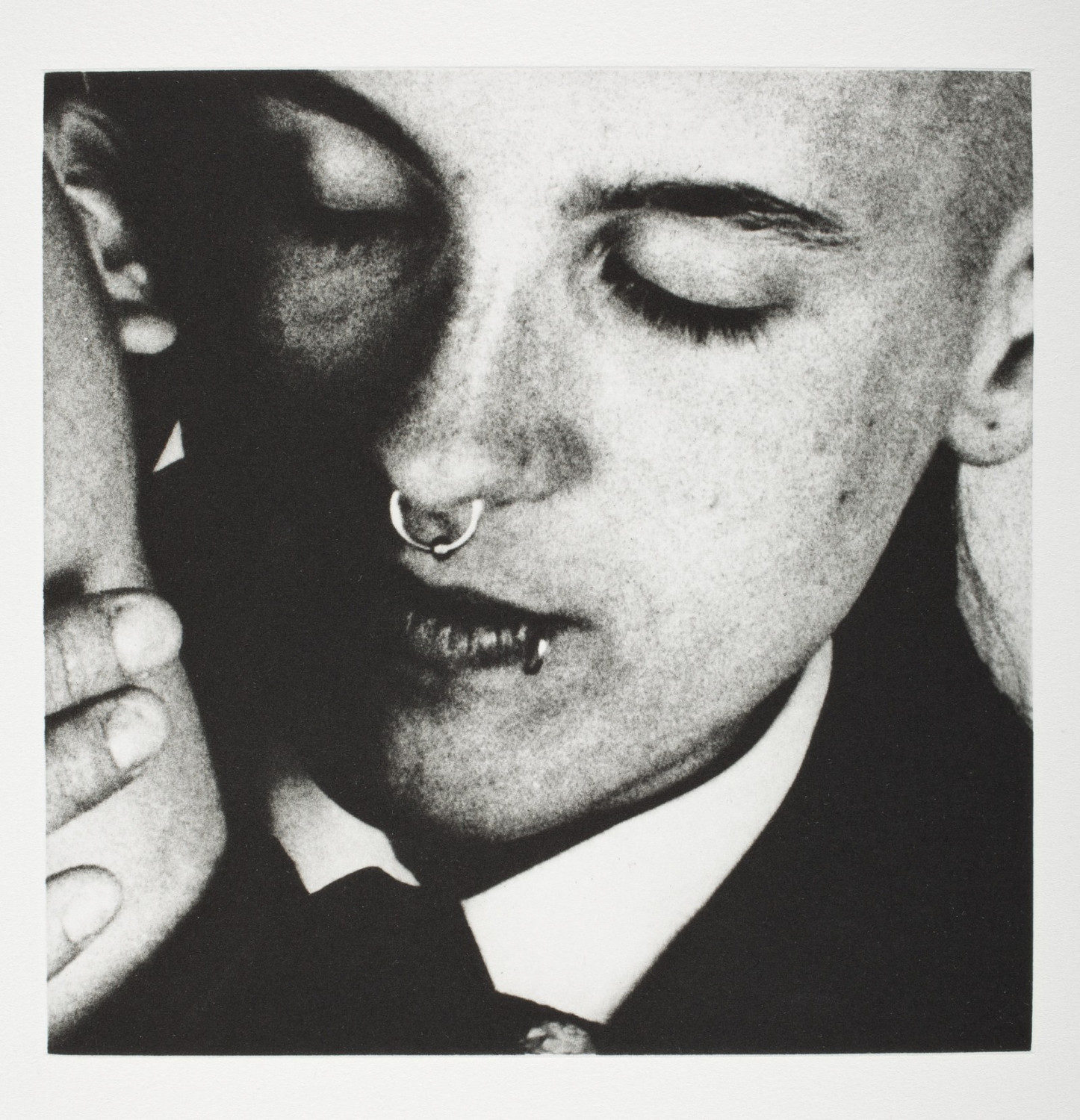

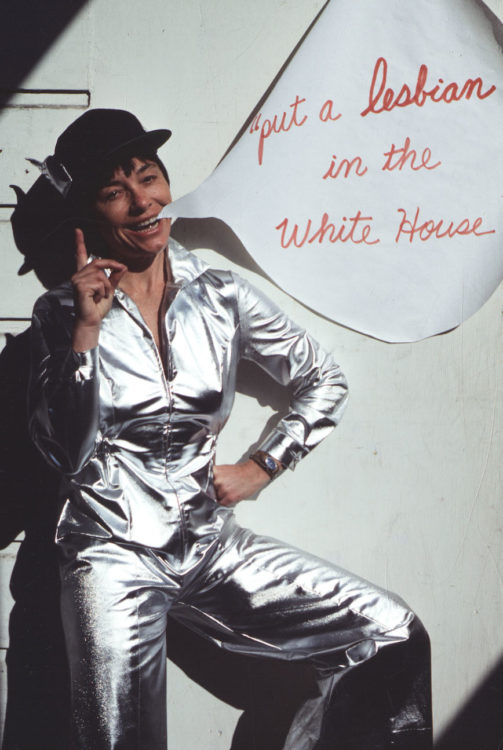

It is impossible to separate the work of Catherine Opie from the emergence of the gay and lesbian movement of the 1970s in the United States, as well as from the queer theories articulated by feminist philosophers during the following decade. The daughter of a conservative businessman, she became aware of her sexuality in her adolescence, and left her family to study in Los Angeles. There, she began socialising with the LGBTQ community, as well as the enthusiasts of fetishism, sadomasochism and bondage. After seeing a documentary by Lewis Hine about child labour at the beginning of the 20th century, she became convinced of the power of the image. After receiving a Master of Fine Arts at the California Institute of Arts (1988), she realised a series of 13 close-up portraits entitled Being and Having in 1991. Photographed against a vivid yellow background, each individual – they appear to be part of the American counterculture scene – has their eyes fixed on the camera, with a beard or moustache, piercings and earrings. The identity of each person represented is written in cursive on a metal plate nailed to the wooden frame: Chicken, Chief, Ingin, Papa Bear. However, certain close-ups reveal that the beards and moustaches are actually hairpieces sported by the artist’s friends from the butch community. C. Opie herself appears under the name of Bo, her male alter-ego, playing with masculine characteristics to highlight the complexity and disparity of her own sexuality.

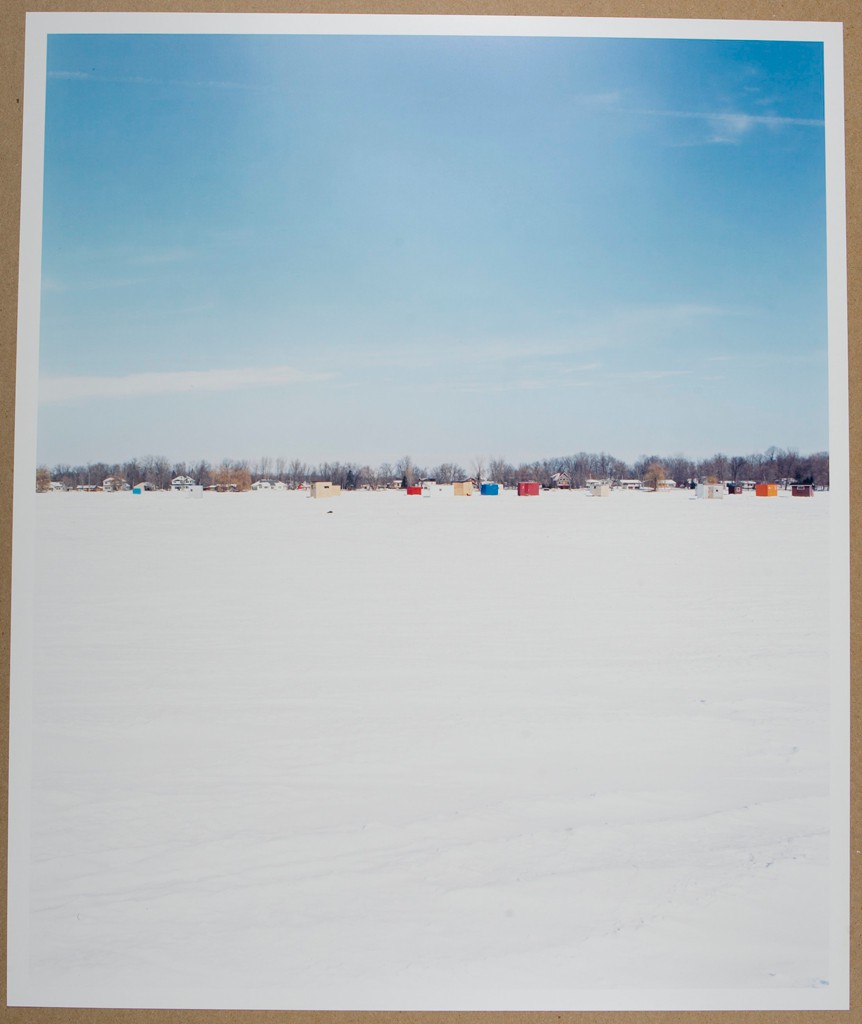

As she states, the women she photographs “don’t want to be men or to pass as men all the time. They just want to borrow male fantasies and play with them.” Between 1993 and 1997, she extensively photographed the sadomasochist, transsexual, and drag scenes for the series Portraits. As a disapproving act of how the leather community was depicted within the dominant culture, she chose to highlight the majestic character of the people she photographed, rather than focusing on their tattoos and piercings. Inspired by portraits by Hans Holbein, as in Being and Having, she isolated her subjects against vibrantly coloured backgrounds, expanding her palette to blue, brown, green and crimson. The academic form of these portraits gives a distinctiveness and dignity to the sitters, whose images are anything but conventional. This use of the canons of classical art history allows for the spectator to better understand her work and to contemplate an image she or he would not otherwise consider. For an artistic project about AIDs in 2000, she realised the series Large Format Polaroid, an homage to the sadomasochist performances of her friend, actor Ron Athey, who had been HIV positive for two years at the time. These life-size photographs – a technical tour de force – were realised with a Polaroid camera capable of producing large format images. In a baroque setting, dramatized by the lighting, the artist shows R. Athey, among others, as a modern version of Saint Sebastian, tattooed from head to toe lying on a death bead, his arm pierced with syringes – an image both beautiful and terrifying. In 2011 C. Opie left the queer universe to dedicate her photography to architecture and deserted landscapes, notably in the series Icehouses (2001). Set against an almost monochromatic white background between ice and sky, the colourful icehouses of the fishermen from Minnesota are aligned on the ice, at times barely visible in the vast, foggy landscape, giving an abstract dimension to these clichés. Each negative is then digitally reworked to ensure the consistency of white tones and the uniformity of the horizon line. In the same spirit, the series Surfers (2001) takes the viewer to Malibu, where, far in the distance, surfers wait in vain for the waves in the immensity of the Pacific Ocean, the almost imperceptible horizon merging with the sky. The artist later returned to a more humanist photography with a series about life in and around the house (2004), as well as another composed of portraits of children (2005). In 2004, after winning the Larry Aldrich prize, she exhibited her works at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield (Connecticut). In 2009, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York presented a retrospective, assembling the most successful synthesis of her work to date.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Catherine Opie - talk

Catherine Opie - talk  Catherine Opie in conversation with Jasper Sharp

Catherine Opie in conversation with Jasper Sharp  Catherine Opie - Photography, Painting and Portraiture | TateShots

Catherine Opie - Photography, Painting and Portraiture | TateShots