Chantal Akerman

Schmid, Marion, Chantal Akerman, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2011.

→Akerman, Chantal, Autoportrait en cinéaste, Paris, Cahiers du cinéma, 2004.

→Foster, Gwendolyn Audrey (ed.), Identity and Memory: The Films of Chantal Akerman, Wiltshire, Flick Books, 1999.

All the World’s Futures, Venise Biennale, Venise, Arsenale, May 9 – November 22, 2016

→Chantal Akerman: Too Far, Too Close, Museum for Contemporary Art, Antwerp, February 10 – June 10, 2012.

→Chantal Akerman, Centre Pompidou, Paris, April 28 – June 7, 2004.

Belgian filmmaker and visual artist.

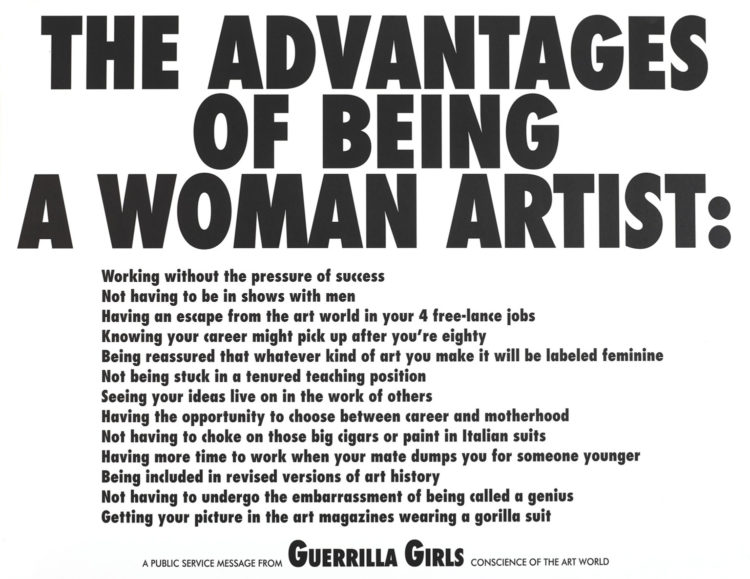

Between 1968 and 2015 Chantal Akerman created a prolific and multifaceted oeuvre that cast its observant, steady gaze on the slow pace of daily life highlighting themes of origin, solitude and wandering, but also love and sexuality.

Born into a Jewish immigrant family from Poland, C. Akerman attended a film school for a brief period from 1967 to 1968, before directing her first short, Blow Up My Town (1968), in which she played the role of a young woman gleefully creating havoc in her kitchen before blowing both it and herself up. In 1971 she discovered experimental American filmmaking through Yvonne Rainer (born 1934) and Michael Snow (born 1928), from whom she borrowed a kind of formal, non-narrative radicalism for her first feature-length film, Hotel Monterey (1972), a silent movie exploring the rooms of a seedy New York hotel in long takes, a formal approach that was to become one of the hallmarks of her style.

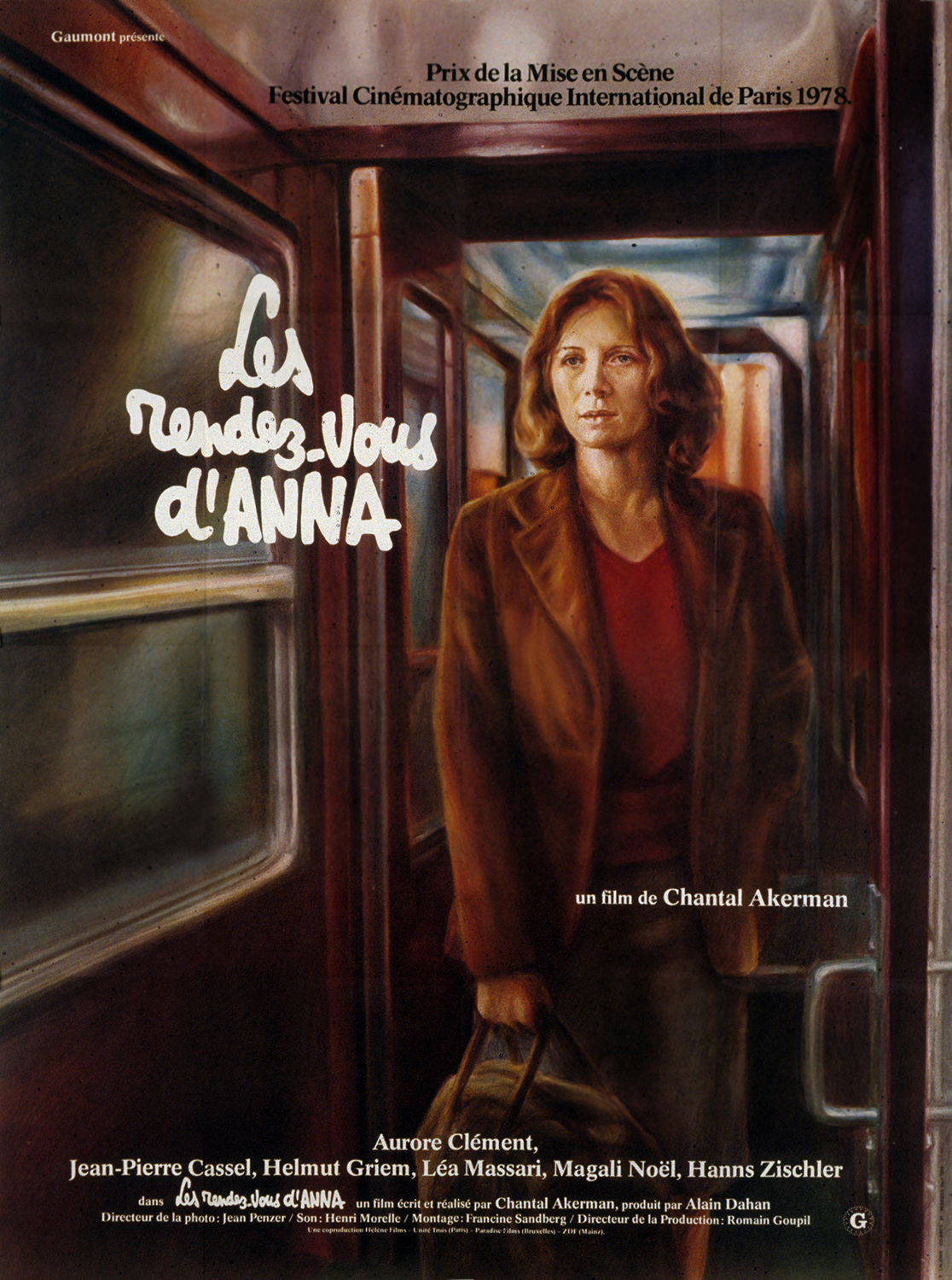

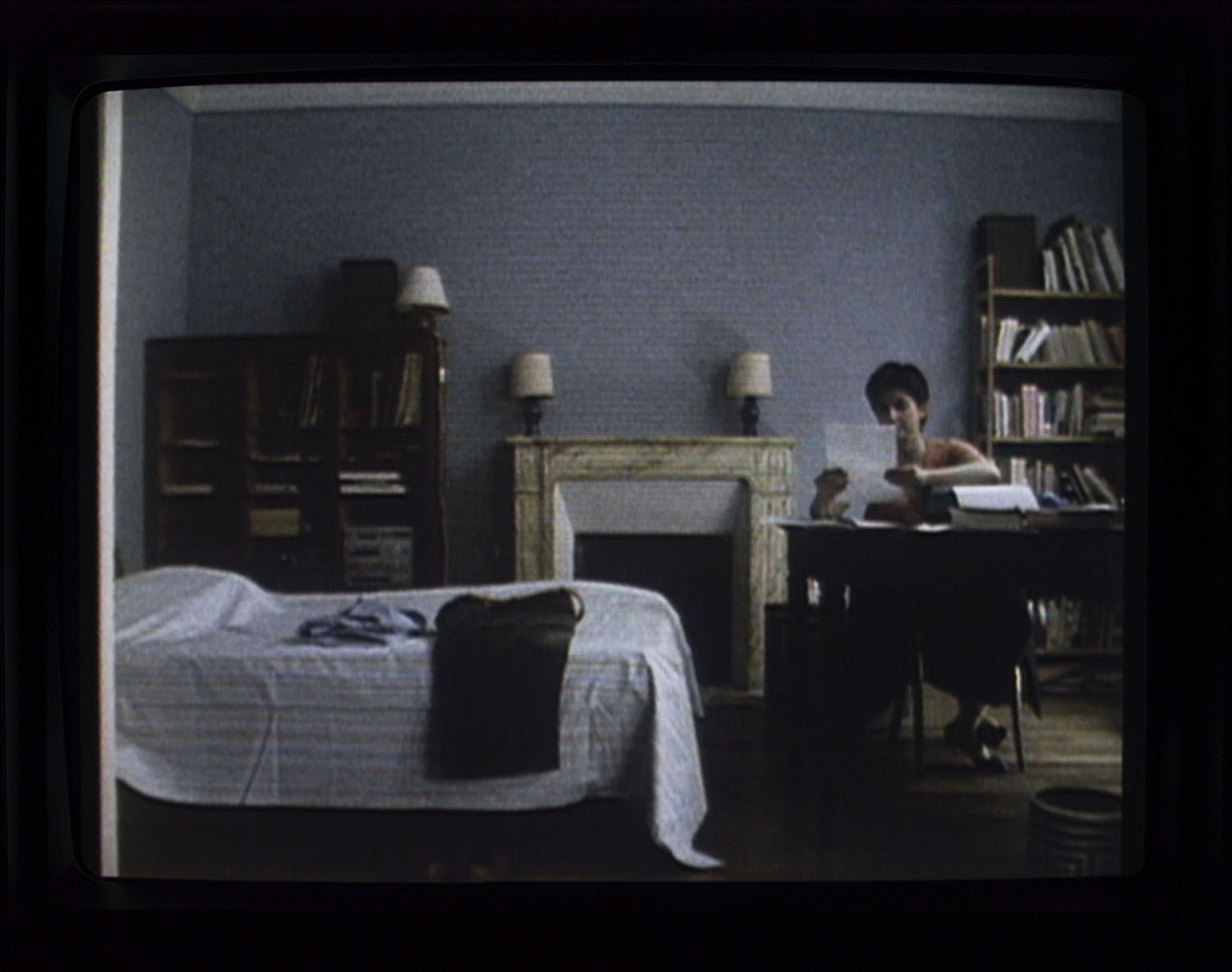

In 1974 C. Akerman directed her first fictional feature film, Je, tu, il, elle [I, you, he, she] in which she broached the topic of her homosexuality: following a break-up, a young woman shuts herself away in her apartment but moves out a month later, hitching a lift with a lorry driver to meet up with her ex-lover. It was only with Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), however, that C. Akerman really made a name for herself. Delphine Seyrig (1932-1990) plays a widow with a young son whose life revolves around her domestic chores and occasional forays into prostitution. This routine, its silent, repetitive gestures underpinning the entire substance of the film, is shattered when she reaches orgasm with one of her clients and then murders him. In News from Home (1976) and Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978) C. Akerman ventured more explicitly into the autobiographical subplot running through each one of her films. In the first she reads the letters that her mother Natalia, the only member of the family to have survived Auschwitz, sent her when she was in New York; her mother’s silence surrounding the Holocaust was to become a recurring theme in C. Akerman’s oeuvre. The second follows a young filmmaker as she travels from city to city showing her films.

From the 1980s until her death C. Akerman continually broadened her palette while maintaining her explorations of the themes she had made her own from her earliest films. Love and sex are always at the heart of her fictional works, as in Toute une nuit [All Night Long, 1982], in which she follows over one night the romantic ups and downs of 24 people, the musical Golden Eighties (1986) or the melodrama Nuit et jour [Night and Day, 1991]. C. Akerman also directed a number of documentaries which delve into issues of belonging, exile and violence: Histoires d’Amérique: Food, Family and Philosophy (1988), which features accounts of Jewish immigrant life in the United States, D’Est (1993), devoted to countries and inhabitants from the former Soviet bloc, which she transformed into a multimedia installation in 1995, and From the Other Side, on the topic of Mexican immigration to the United States. In 2006, in Down There, she recounted her month’s experience in Tel Aviv and reflected on her childhood and Jewishness. In 2014 she was devastated by the death of her mother, to whom she had devoted a book in 2013 (published in English as My Mother Laughs in 2019), also making her the subject not only of her last film, No Home Movie (2015), but of her entire oeuvre.

On 5 October 2015, C. Akerman committed suicide in Paris. In the course of her career, she received nominations in festivals such as Cannes, Berlin, Venice and Locarno, among others, and a great many retrospectives have also been dedicated to her, by the Centre Georges-Pompidou (2004), the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (2006) and the Cinémathèque de Paris (2018).

Chantal Akerman "Je fais de l’art avec une femme qui fait la vaisselle" | Archive INA (French)

Chantal Akerman "Je fais de l’art avec une femme qui fait la vaisselle" | Archive INA (French)  Parlons cinéma | Chantal Akerman, festival de Canne 1977 (French)

Parlons cinéma | Chantal Akerman, festival de Canne 1977 (French)  Chantal Akerman on Jeanne Dielman, 2009 | Criterion Collection (French)

Chantal Akerman on Jeanne Dielman, 2009 | Criterion Collection (French)