Charmion von Wiegand

Wismer, Maja (ed.), Charmion von Wiegand. Expanding Modernism, exh. cat., Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel [2023], München, Basel, Prestel, 2021.

→Hersh, Jennifer Newton, Abstraction, Spiritualism and Social Justice. The Art and Writing of Charmion von Wiegand. PhD-Dissertation, City University of New York, New York, 1998.

→Charmion von Wiegand. Her Art and Life, exh. cat., Bass Museum of Art, Miami Beach [February – March 1982], Miami Beach, Bass Museum, 1982.

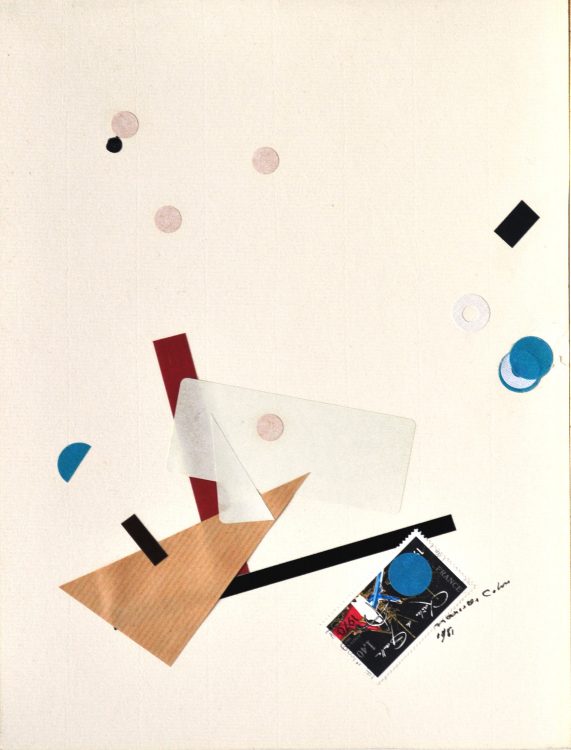

Charmion von Wiegand: Spirit and form. Collages, 1946-1963, Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, New York, September 10 – October 31, 1998.

→Charmion von Wiegand. Her Art and Life, Bass Museum of Art, Miami Beach, February – March 1982.

→Charmion von Wiegand. Retrospective, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, May 28 – June 29, 1974.

American painter.

Born in Chicago in 1896, Charmion von Wiegand grew up in Berlin and lived in New York, Connecticut and Moscow. She worked as a journalist, art critic, curator and abstract painter. While studying journalism and attending classes in art history at Barnard College and Columbia University in New York, C. Von Wiegand developed an interest in Chinese, Indian and Persian cultures and arts. Although her main artistic work dates from between the 1940s and the 1970s, C. Von Wiegand first exhibited her own paintings as early as 1928. In the 1930s, however, she worked and was regarded more as a journalist and art critic than as an artist. Her initial involvement with aesthetic theories and abstraction for art magazines, including the Art Front and many more, brought her into contact with artists and curators who nurtured and shaped her artistic development. Her political views, influenced by her interest in socialist writings, also manifested in her view on art at the time: she believed art should be revolutionary, no longer elitist, or exclusive.

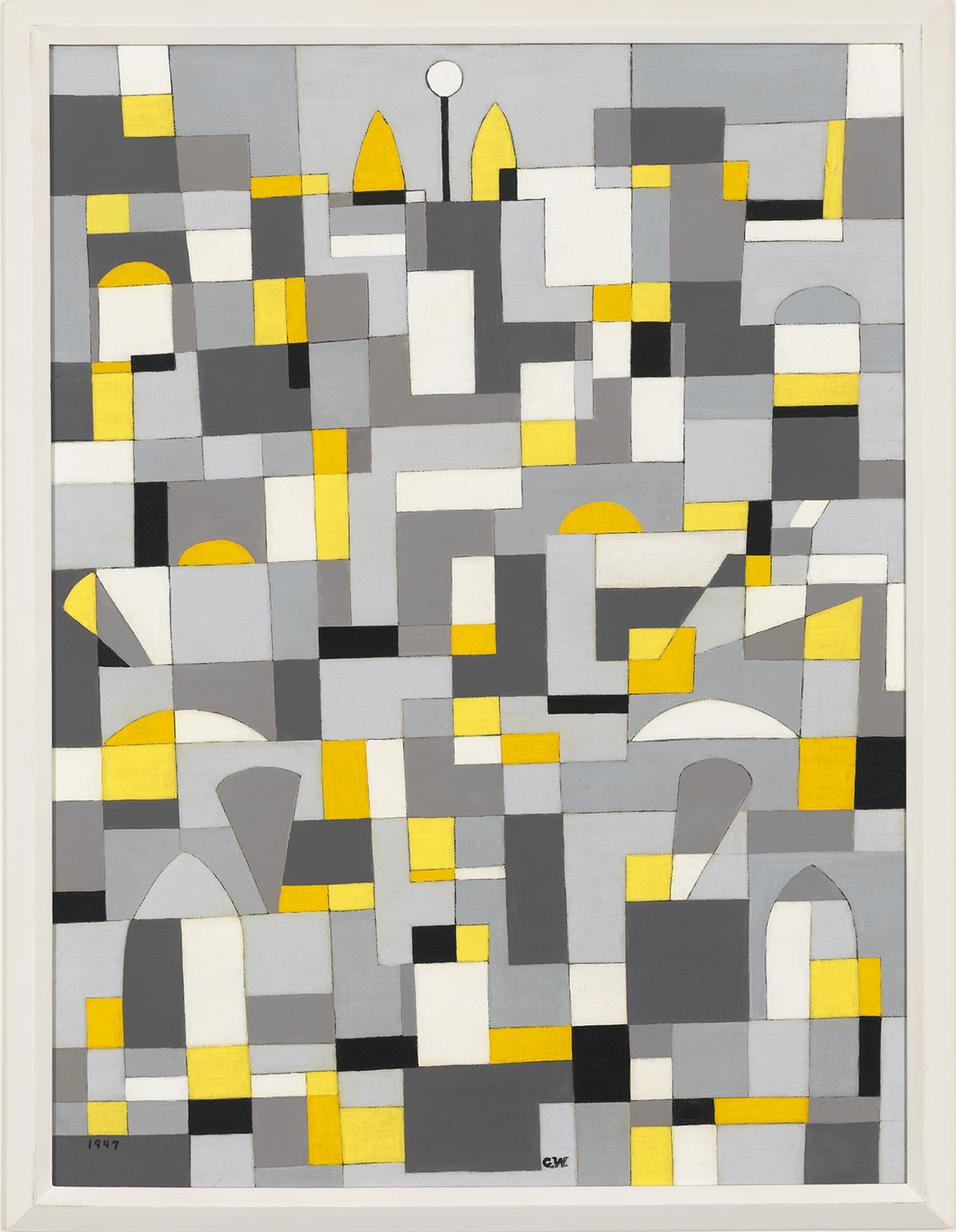

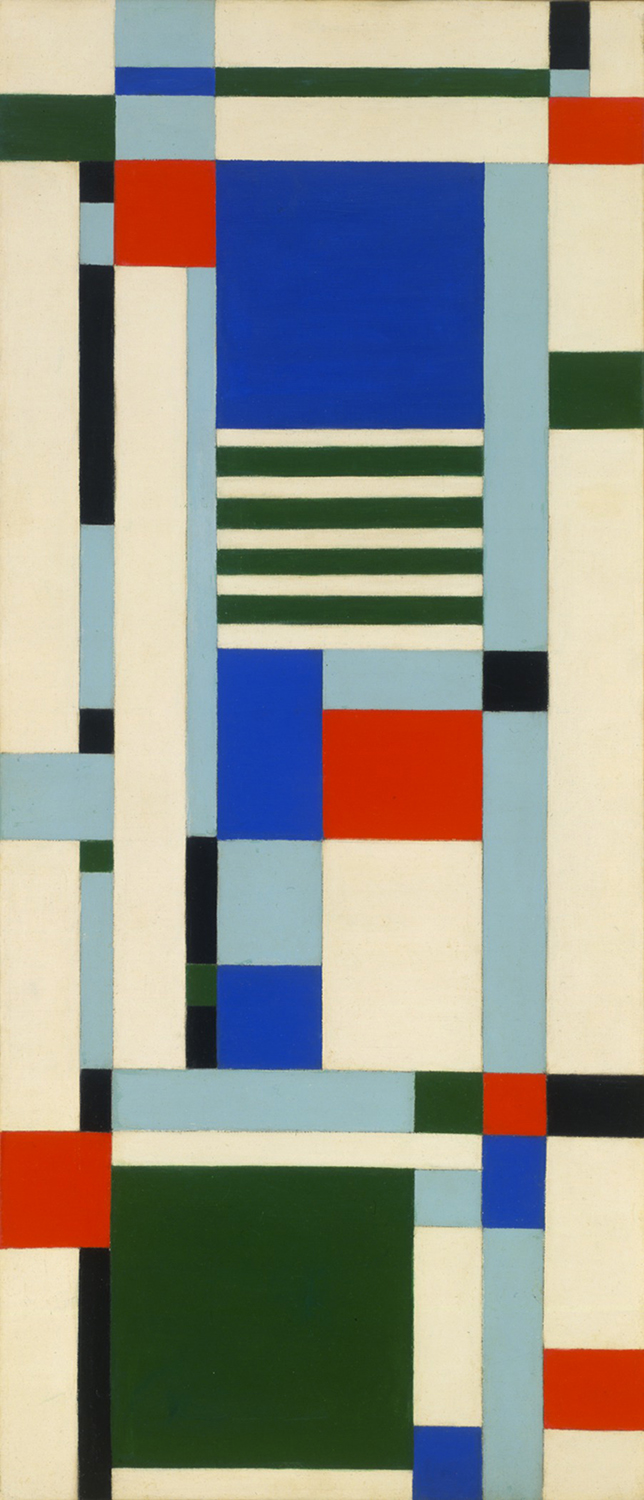

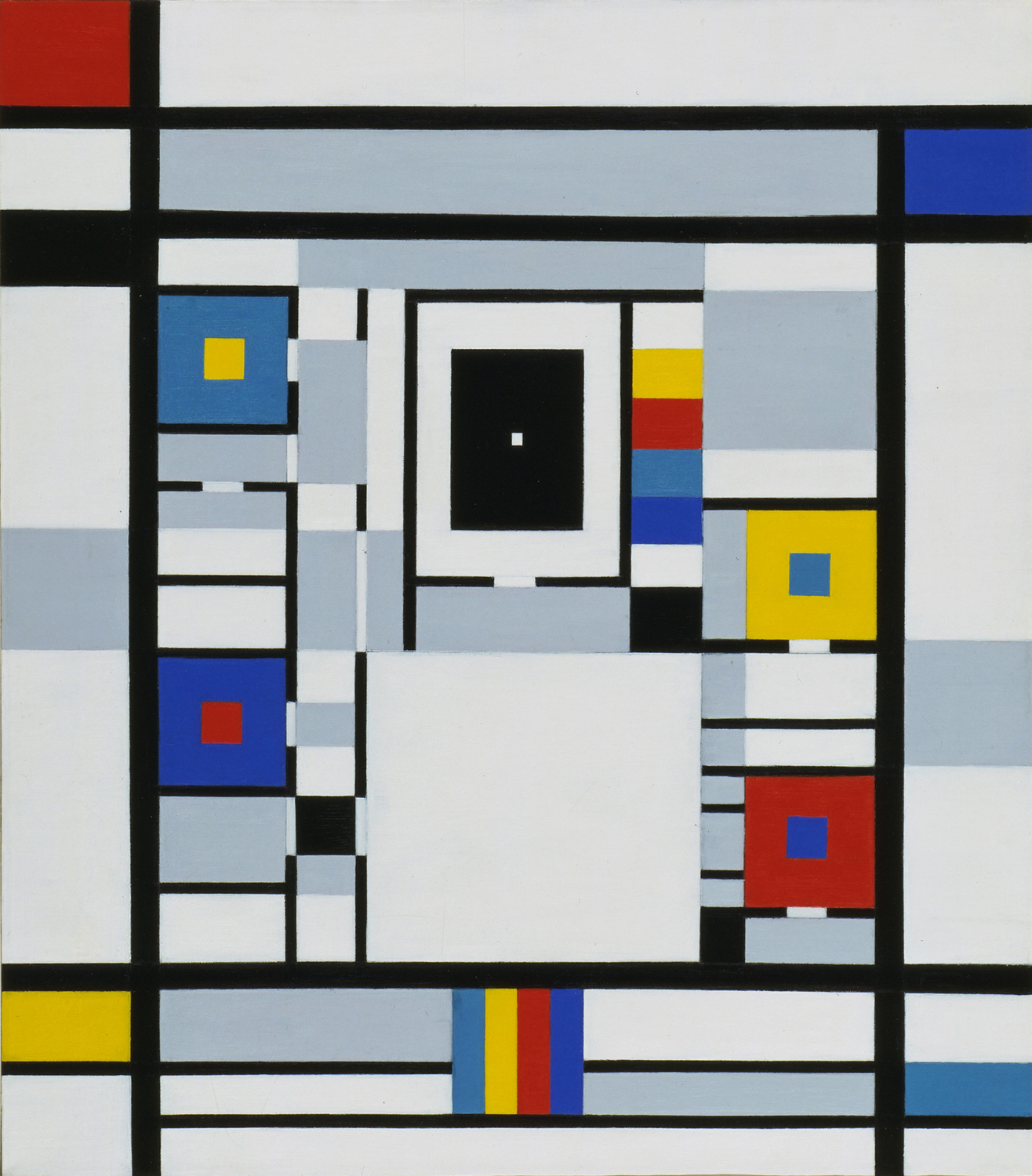

In the 1940s she increasingly resumed her artistic practice; automatic drawing and an engagement with biomorphism are evident in works such as Ominous Form (1946). At the same time, C. Von Wiegand developed a more geometric formal language in works such as City Lights (1947), reminiscent of the work of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) and testifying to their shared interest in urban space. As a close friend of his, she wrote articles about his work, as well as translating and revising his texts from 1942 until his death in 1944.

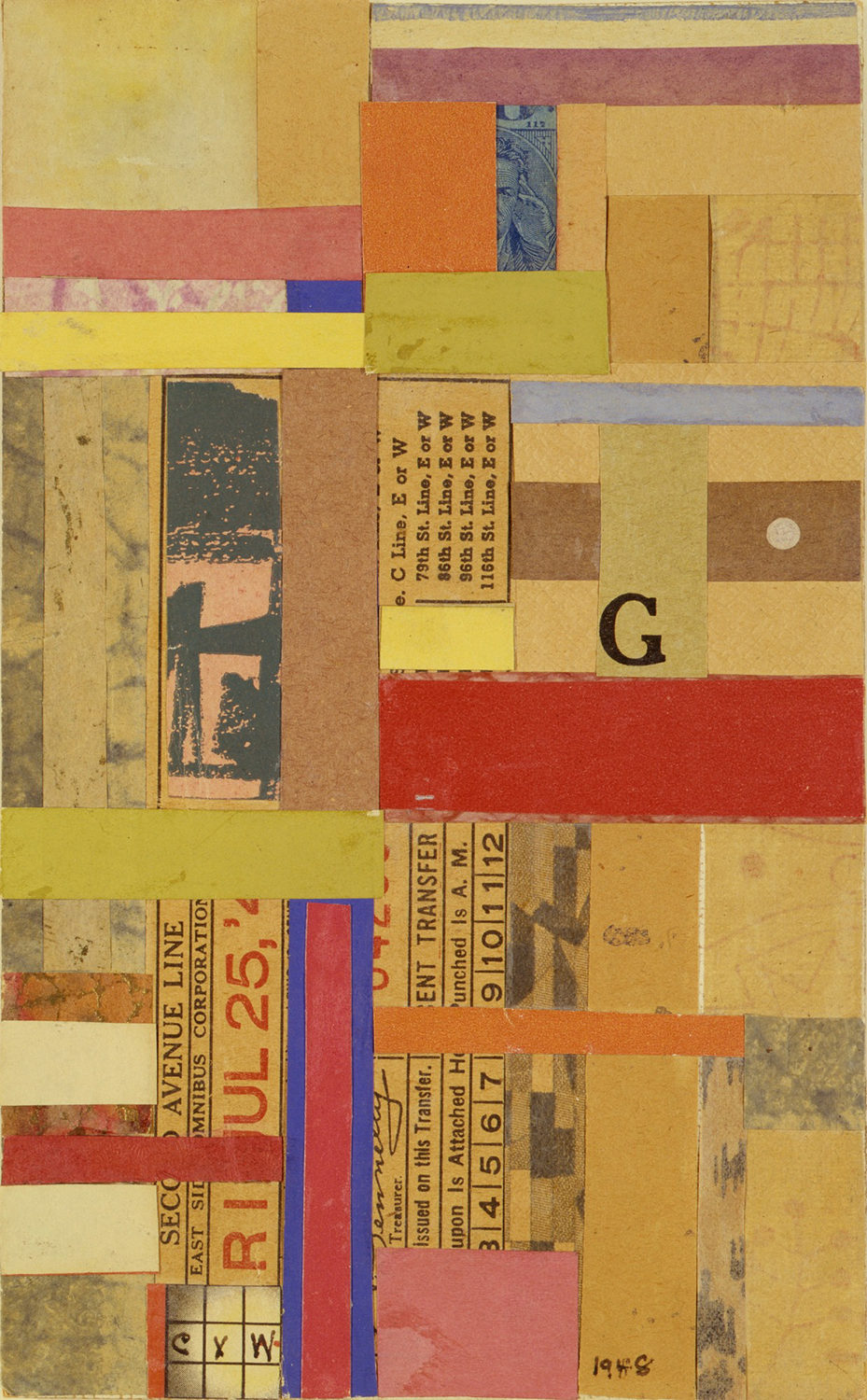

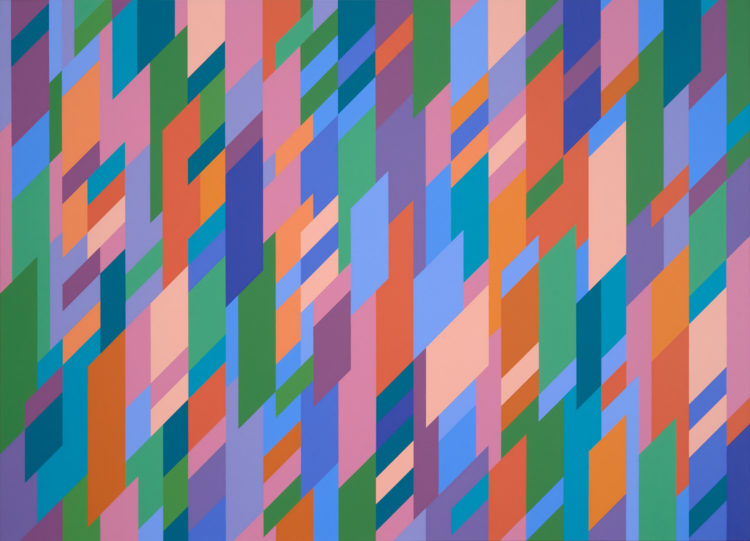

From 1947 C. von Wiegand intensified her studies of non-Western art and spiritual topics, sharing her interest in East Asian cultures and religion in an ongoing exchange with artist Mark Tobey (1890-1976). Consequently, a reorientation in her work is evident from the late 1940s.

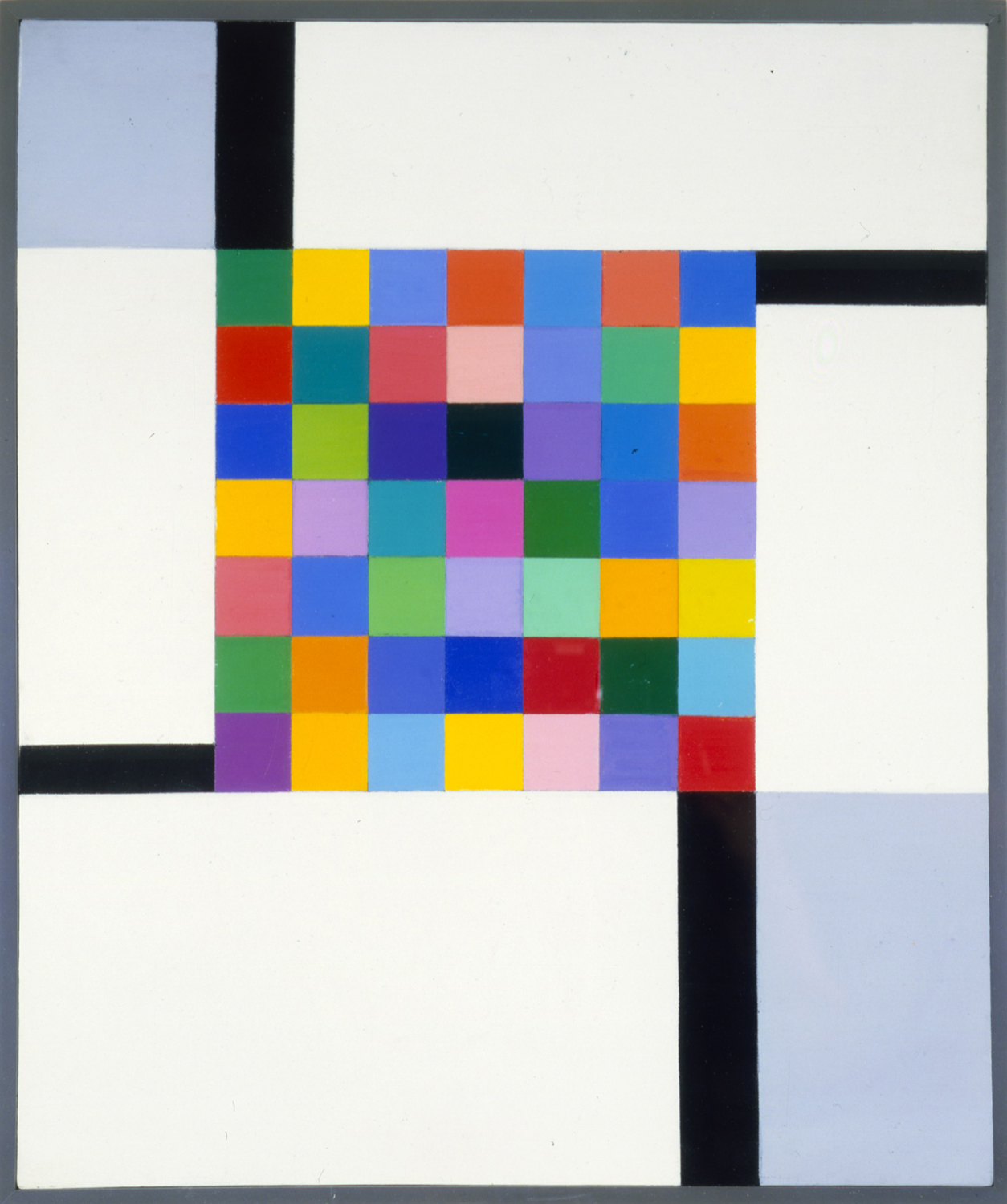

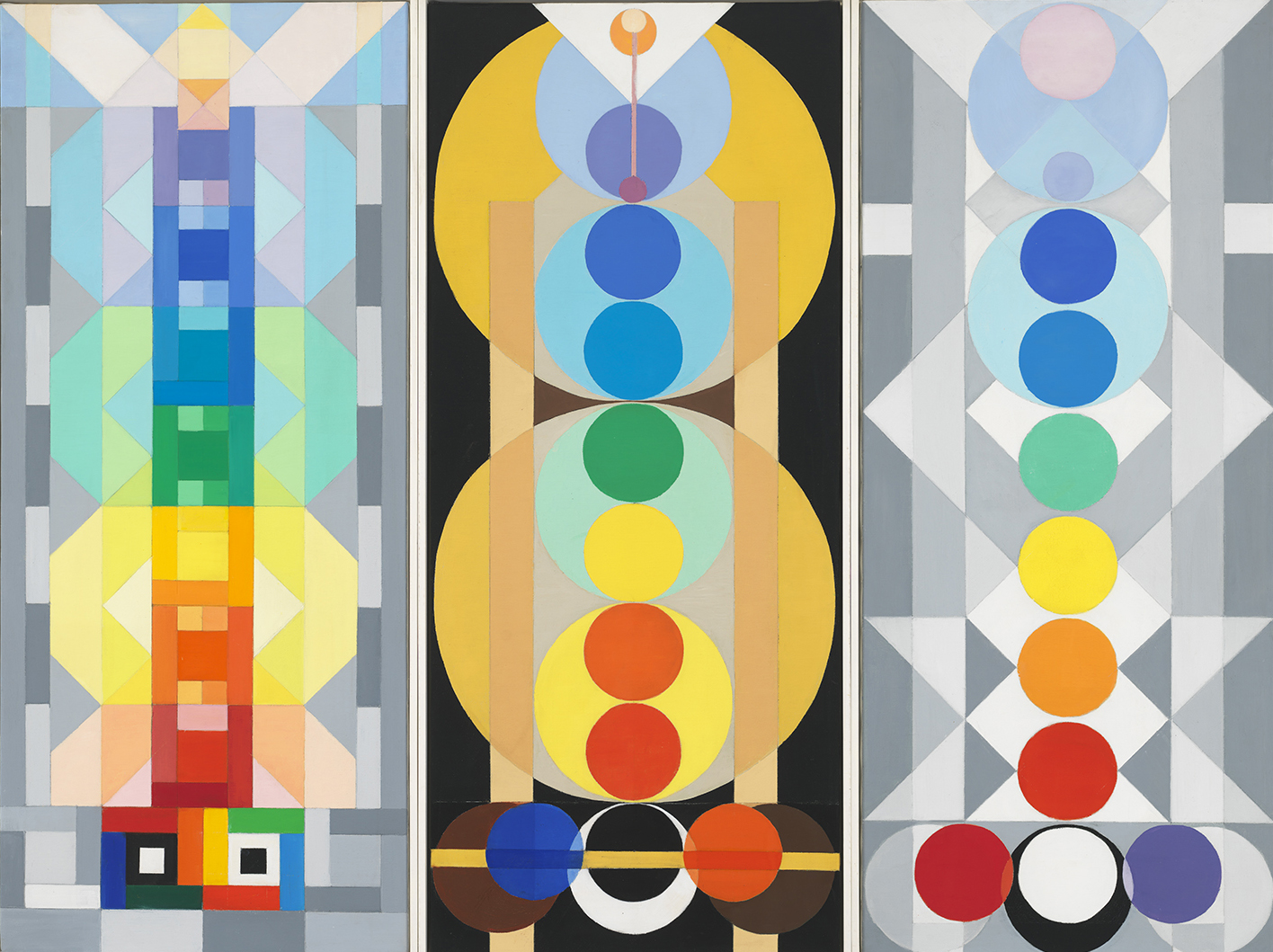

Not as religious objects per se, but as testimony to C. von Wiegand’s spiritual practice, The Great Field of Action or the 64 Hexagrams (1953), or The Chakras (1958-1959) trace back to her studies of Taoism and Tantra. In the 1960s – reinforced by C. Von Wiegand’s acquaintance with her future Buddhist teacher Khyongla Rato Rinpoche in 1967, later founder of the first Tibet Center in New York and recipient of C. Von Wiegand’s estate – her work shifted further from spectral tantric expression to the use of Tibetan Buddhist symbols such as the altar in To the Adi Buddha (1968-1970).

In her later works, C. Von Wiegand brought together the various influences on her artistic practice, and Triptych, Number 700 (1961) could be considered the culmination of her oeuvre. The multifaceted nature of the artist, combined with her experiences as a writer and curator, makes it difficult to categorize her, while simultaneously making her stand out. Before her death in 1983, C. Von Wiegand had various group and solo shows, as well as retrospectives in Europe and the United States and was awarded the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award in 1982.