Claude Vignon (Marie-Noémi Cadiot-Constant Rouvier, dite)

Rivière Anne (ed.), “Claude Vignon”, Dictionnaire des sculptrices en France, Paris, Mare & Martin, 2017, p. 524-525.

→Harvey David Allen, “Forgotten Feminist : Claude Vignon (1828-1888), revolutionary and femme de lettres”, Women’s History Review, Volume 13, Numéro 4, 2004, p. 559-583.

→Stéphanie Deschamps, “Noémie Constant dite Claude Vignon (1828-1888) : ‘l’ébauchoir du sculpteur et la plume du romancier’ (Zola)”, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire de l’art français, 2003, p. 303-328.

→Brogniez Laurence, “Claude Vignon, une femme ‘surexposée’ sous le Second Empire”, in David Baguley (ed.), Les Arts et la Littérature sous le Second Empire, University of Durham, 2003, p. 149-165.

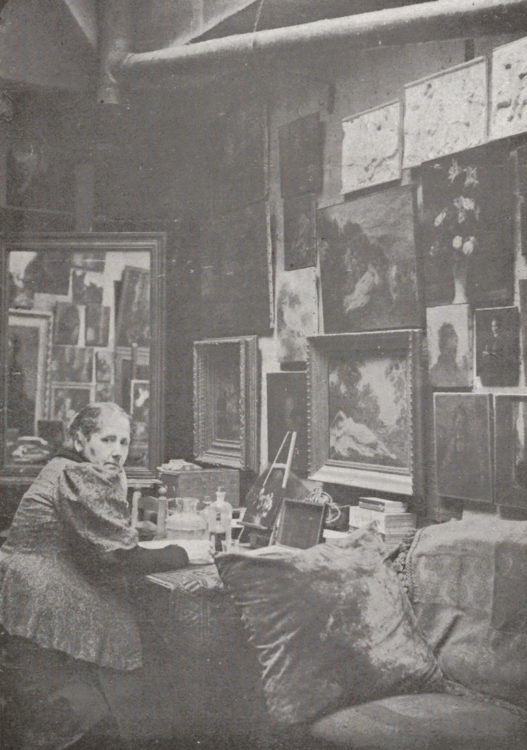

Exposition des Femmes célèbres du XIXe siècle, par Marguerite Durand, 1922

French sculptor, writer and critic.

Born into a wealthy family, Marie-Noémi Cadiot was sent to a boarding school in Choisy-le-Roi. She eloped in 1846 at the age of 17 with former seminarian, painter and future occultist figure Alphonse-Louis Constant (1810-1875), with whom she experienced the 1848 Revolution. Together, they founded the newspaper Le Tribun du peuple and the organisation Le Club de la Montagne. M.-N. Cadiot took an active part in feminist movements, particularly the Club de la Voix des Femmes, Club des Vésuviennes, and Banquet Régénérateur des Femmes Démocrates et Socialistes. In the tradition of Saint-Simon, she chose to sign the articles she wrote for La Voix des femmes with her first names to assert her independence. She also wrote for Le Tintamarre and Le Moniteur du soir under the pen name Claude Vignon, which she borrowed from a Balzac character.

In 1849 she became a pupil of sculptor James Pradier (1790-1852). She made her debut at the Salon in 1852 under the name Mme Noémi Constant with her plaster cast for L’Enfance de Bacchus [Bacchus’ Childhood], a commissioned work for the Ministry of the Interior, the marble version of which, Bacchus enfant [Young Bacchus], she presented in 1853. After having her marriage anulled in 1865, she was able to use her pseudonym as her formal name as from 1866, thanks to a decree from the emperor. Until 1885 she exhibited ronde-bosse and bas-relief pieces inspired by mythology, Greece and Italy (Dans les prés d’Arcadie or Idylle [In the fields of Arcadia, or Idyll], a marble group shown at the 1855 World’s Fair and at the Salon in 1857; Daphné, presented at the 1867 World’s Fair), as well as portraits (Pierre Gavarni and Pierre Gavarni et Portrait de M. Lefuel membre de l’Institut, architecte de l’Empereur [Portrait of M. Lefuel, member of the Institut, architect for the Emperor], 1857; Portrait of Baron Haussmann, 1870; Monsieur Thiers, premier président de la République française [Monsieur Thiers, first president of the French Republic], 1879). Commissioned by the State in 1876 and presented at the 1878 World’s Fair, Le Pêcheur à l’épervier [The fisherman] was one of the greatest successes of her career. The marble ronde-bosse followed in the footsteps of François Rude (1784-1855) and his Jeune pêcheur napolitain jouant avec une tortue [Young Neapolitan fisherman playing with a turtle, 1833] and of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827-1875) and his Pêcheur à la coquille [Fisherman with a shell, 1858]. C. Vignon also showed her works at the Salon organised by the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs (Union of women painters and sculptors) in 1882, 1885 and 1886.

Thanks to her friendship with Hector Lefuel, chief architect at the Louvre, she was commissioned for decorative elements for the Louvre (several bas-reliefs portraying the spirits of the arts for the library staircase, known as the Lefuel staircase; Le Printemps [Spring] for the Henri IV wing and L’Automne [Autumn] for the Henri II wing), the Tuileries (an oval medallion for the Empress’s staircase portraying three spirits carrying the emblems of the Empire) and the Minister of State’s Hotel (overdoors La Danse [Dance], La Musique [Music] and La Causerie [Conversation]). With the support of Empress Eugénie, from 1862 she was granted an annual pension. She created the central bas-relief for the Saint-Michel Fountain in Paris, which was installed in 1863.

In addition to her production as a sculptor, C. Vignon also worked as an art critic from 1851. She gave prominence to sculpture – “statuary is the highest and most incorruptible manifestation of art” (1853 Salon) – eclecticism – describing herself as “classic by necessity and eclectic by nature” (1852 Salon) – and the depoliticisation of art. In 1866 Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), whose idealism she admired, painted four canvases for her townhouse in Passy: La Vigilance [Vigilance], La Fantaisie [Ingenuity], L’Histoire [History] and Le Recueillement [Contemplation]. C. Vignon was also a parliamentary correspondent for L’Indépendance belge, a liberal newspaper that skirted censorship. As the head of the “Chamber column”, she was the first woman to gain access to the institution. Her articles, accounts and serials were also published in several other papers, such as Le Moniteur universel (using the pen name Henri Morel). In 1872 she married Maurice Rouvier, a left-wing journalist and politician who would later become a minister and chair of the Council under the Third Republic. She published several novels and short stories as a writer, most of which were centred around female protagonists (including Élisabeth Verdier in 1875, Révoltée ! in 1878 and Une étrangère [A Stranger] in 1886).

C. Vignon died in 1888. Her tomb at Père-Lachaise Cemetery was adorned with her self-portrait in bronze – now missing – and her attributes: a goose feather and a sculptor’s mallet and chisel. In 1890 M. Rouvier donated a bronze copy of Pêcheur à l’épervier to the town of Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat as a monument in honour of his wife. In 1891 Jules Simon wrote in the preface of a collected volume of some of her writings: “She was both a writer and a sculptor, which was what made her so original. I wonder if this double vocation might perhaps have counted against her. … We find it so hard to encounter one kind of superiority that it must be, in truth, very difficult to have a second imposed upon us” (“Claude Vignon”, Œuvres de Claude Vignon, Paris: Alexandre Lemerre éditeur, 1891, pp. I-II). Marguerite Durand ranked her among the “famous women of the 19th century” in an exhibition she curated in Paris in 1922. Studies have mostly focused on C. Vignon’s career as a critic and journalist but, since the early 2000s, a body of research undertaken by Stéphanie Deschamps-Tan has further highlighted her artistry.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021

FEMMES AU LOUVRE - Stéphanie Deschamps-Tan | Musée du Louvre, March 2018

FEMMES AU LOUVRE - Stéphanie Deschamps-Tan | Musée du Louvre, March 2018