Félicie de Fauveau

Caron Mathieu, “Sculpteur et femme : Félicie de Fauveau (1801-1886) et la transgression des genres”, Romantisme, n° 179, 2018, p. 58-69

→Waresquiel Emmanuel de, Félicie de Fauveau : portrait d’une artiste romantique, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2013

→Mascalchi, Félicie de Fauveau : una scultrice romantica da Parigi a Firenze, Florence, L.S. Olschki, 2012

Félicie de Fauveau et la Vendée, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne, Historial de la Vendée, 2013

→Félicie de Fauveau : l’amazone de la sculpture, catalogue d’exposition, Les Lucs-sur-Boulogne, Historial de la Vendée, February, 15 – May, 19, 2013, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, June, 11 – September 15, 2013, Paris, Gallimard, Musée d’Orsay, 2013

French sculptor and designer of decorative art objects.

Félicie de Fauveau was born to a family of French aristocrats and studied painting with Louis Hersent (1777-1860) before choosing to move on to sculpture – self-taught, as she herself said. After her father’s death, the family moved to Paris in 1827. Her mother Anne-Hippolyte ran an influential salon in the Nouvelle Athènes district, where F. de Fauveau’s studio neighboured that of Ary Scheffer (1795-1858). She became friends with Paul Delaroche (1797-1856), read John Milton, Walter Scott and Lord Byron, and developed a passion for history, heraldry and medieval art.

F. de Fauveau was able to secure a few commissions thanks to close relatives of Charles X and the protection of the influential Duke of Duras, whose daughter Félicie de La Rochejaquelein became her partner. The “two Félicie” maintained a very close relationship, which, despite their physical separation, lasted until the countess’s death in 1883. Years before Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899), F. de Fauveau rejected marriage, cut her hair short around 1830 and often included masculine elements in her outfits.

In order to earn a living and probably driven by a deep ambition, F. de Fauveau worked to become a professional. She was the first French female sculptor to live off her art. At the age of twenty-six, she participated in her first Salon with her relief Queen Christine of Sweden (1827), which earned her a second-class gold medal and appreciation for her history-inspired, romantic-leaning pieces. She was commissioned to design doors for the Louvre and received an order from Count James-Alexandre de Pourtalès for the precious multi-coloured Lamp of Saint Michael (1830) and a Monument to Dante (1830-1836).

In 1830, her life took a turn when Louis-Philippe I acceded to the throne: F. de Fauveau took the side of the Legitimists and joined the rebellion in Vendée with Countess de La Rochejaquelein. She designed emblems for her brothers and sisters in arms in the chivalrous spirit of medieval times. She was arrested and imprisoned for three months, briefly taking up arms again upon being released. The “heroine of Vendée” was forced into exile.

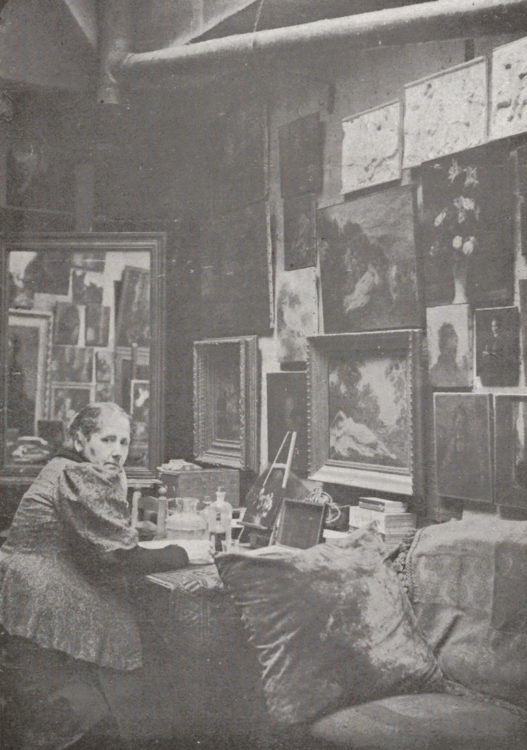

In 1833, the artist fled to her native country – the very Catholic Italy – where she would spend the rest of her life despite the 1837 amnesty, out of loyalty to the Duchess of Berry and the Count of Chambord, of whom she painted several portraits. During her time in Florence her works became increasingly inspired by the Middle Ages and the Italian Renaissance. Her brother Hippolyte de Fauveau (1804-1887) shared her studio, which she supervised with an iron hand. The “casa Fauveau” entertained a cosmopolitan circle of mostly Russian rich aristocrats: Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, her father the Tsar Nicholas I and Prince Anatoly Demidov.

As a great admirer of Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), F. de Fauveau devoted herself to both sculpture and the decorative arts. Such a multidisciplinary approach was disconcerting at the time: in 1839 her Miroir de la Vanité [Mirror of Vanity] was praised by Théophile Gautier but refused by the Salon for its hybrid characteristics. She was known to just as easily design busts and stoups, as well as ceremonial daggers, picture frames, table bells, jewellery, and cane pommels, all intricately detailed and inscribed with Catholic symbols and Latin quotes.

F. de Fauveau’s work was later mostly forgotten, but was rediscovered thanks to the considerable research undertaken by art historian Jacques de Caso for a monographic exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay and Historial de la Vendée in 2013. The musée des Augustins in Toulouse is home to several of her sculptures and the Musée du Louvre recently acquired two of her masterpieces: the Lampe de saint Michel (1830) and Sainte Réparate (1855).

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021