Colette Brunschwig

Micucci, Marjorie (ed.), Colette Brunschwig. Peindre l’ultime espace, Paris, Manuella, 2021

→Benoît Decron, Daniel Segala, Christophe Hazemann, Femmes années 50. Au fil de l’abstraction, peinture et sculpture, exh. cat., Musée Soulages, Rodez (December 14, 2009 – October 31, 2020), Paris, Hazan, 2019

→Colette Brunschwig, « Sur Claude Monet », Lignes, n° 38, Paris, Hazan, 1990

Colette Brunschwig & Claude Monet in conversation, Galerie Jocelyn Wolff, Paris, January 9 – February 12, 2022

→Colette Brunschwig. La Roue Revisited, OSMOS, New York, 2017-2018, December 13, 2017 – February 9, 2018

→Colette Brunschwig, Galerie Colette Allendy, Paris, May 20 – June 3, 1955

French abstract painter.

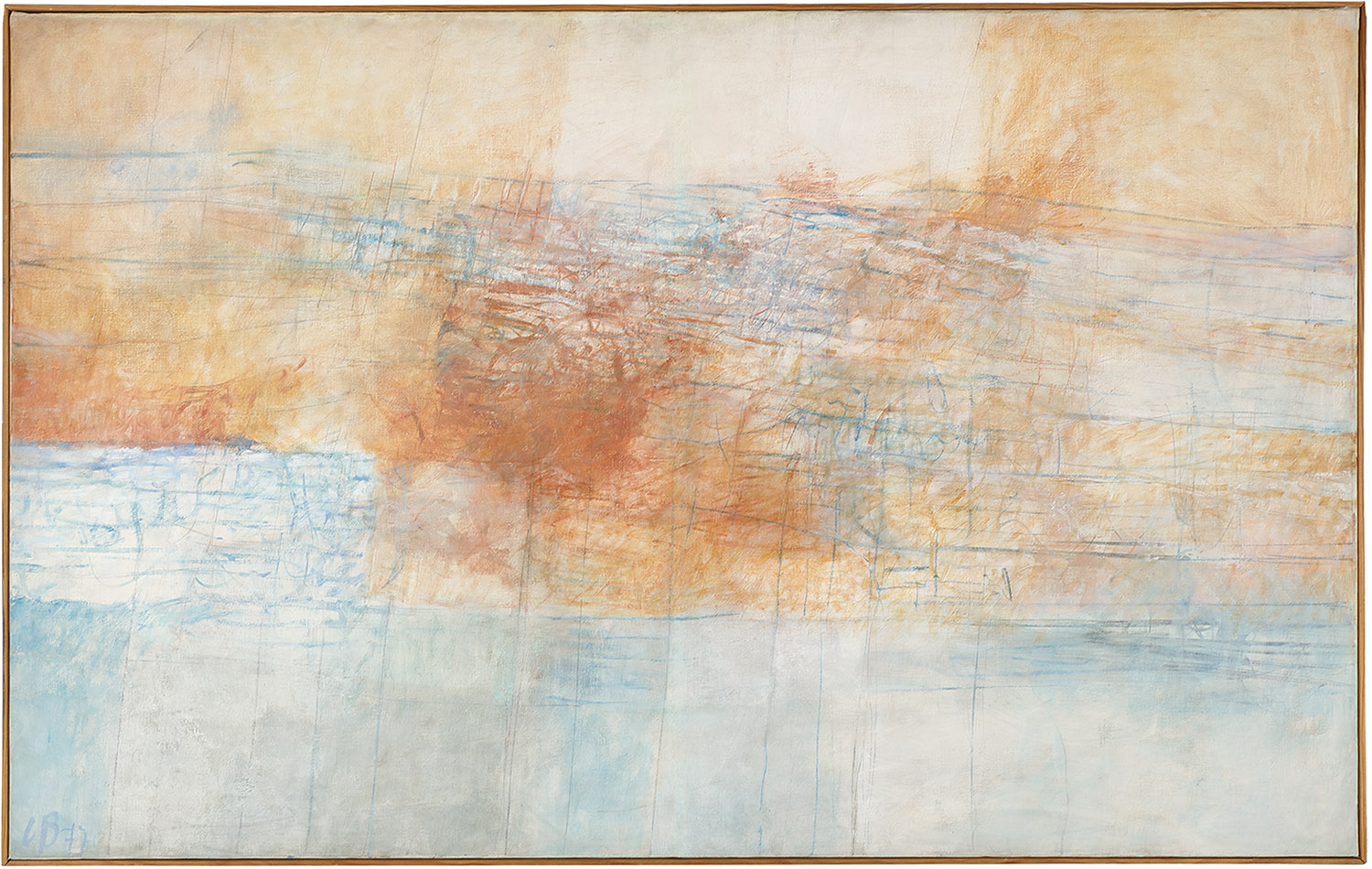

In 1945, when she was around twenty years old, Brunschwig moved to Paris to study painting in the immediate Post-war period: “white years” (1945-1950) in which society was left reeling from the shock of the recent annihilation. After a brief stint at the declining Academie Julian, she began to frequent the studio of the painter Jean Souverbie (1891-1981). From 1946 to 1949, she followed the teachings of André Lhote (1885-1962) who opened her eyes to the issues of abstraction. At the time, the young woman was fascinated by the work of Claude Monet (1840-1926), to whom she later devoted an essay celebrating the “slow meltdown of the form,” which reached its paroxysm with the Nymphéas. His painting, in which “the top and the bottom, the right and the left are oriented, meet and get lost,” inspired C. Brunschwig to create works that were devoid of horizons but not of depth, pure abysses of darkness and light. Different generations of Parisian galleries have accompanied her work: in the 1970s, the galleries Nane Stern and La Roue; in the 1980s and 1990s, Bernard Bouche, Clivages and Jaquester; in the 2000s and 2010s, Convergences and Jocelyn Wolff. In 2020, she took part in the group exhibition Femmes années 50. Au fil de l’abstraction, peinture et sculpture at the Soulages Museum in Rodez.

In the 1950s, she exhibited at the Colette Allendy gallery, an important source of diffusion of a multifaceted abstraction: lyrical, tachist, informal or monochrome, but also calligraphic, with an exhibition devoted to modern calligraphic painting in Japan in 1955. In the late 1960s, Brunschwig embraced Eastern philosophy, initiated by an article in the journal Hermès: “Le Vide à la Source de l’Inspiration chez les Peintres lettrés de la Chine ancienne” [The Void at the Source of Inspiration amongst the Literati Painters of Ancient China]. Through Pierre Soulages (born in1919), she met the Korean painter Lee Ungno, whose abstract signs she praised as being “full of the meanings of a true language.” Brunschwig’s ink washes and paintings can also be apprehended on the basis of these Oriental, Buddhist and Zen traditions, with an inner light like the “phosphorescence of each dust” according to Tadao Takemoto (Japanese translator), contracting an intensity in which “the whole duration of the experience [is] absorbed” for François Cheng (calligrapher- poet).

“For a very long time,” explained Brunschwig, “Painting conveyed Meaning. Today the technique of Painting has become Meaning itself. The Necessity from which Painting draws its strength is the fact of being this counterpower to the domination of images.” Very often left untitled, sometimes marked with imprints or scratches, Brunschwig’s paintings speak in their very matter. In the thickness of the blacks, they speak of the dense, opaque darkness which the artist witnessed as a child, fleeing Le Havre with her family when it was bombarded and set on fire in 1944. The painter worked from the void, but also from chaos and erasure. Attending seminars by the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas, corresponding with the philologist Jean Bollack, illustrating the poetry of Paul Celan, Brunschwig belonged to a constellation of surviving Jewish intellectuals working to transcend what E. Lévinas called “a tumor in the memory”, the unthinkable and the unrepresentable. In drawings integrating the third dimension, in grey modulations, coloured outcrops or “meaningless signs,” she worked from the 1950s, with infinite constancy, to bear witness to a “silent glow”.

Marie Marfaing (réal.), André Marfaing (1925-1987), with the testamony of Colette Brunschwig, 2007, 12’18’’ - 16’52’’

Marie Marfaing (réal.), André Marfaing (1925-1987), with the testamony of Colette Brunschwig, 2007, 12’18’’ - 16’52’’