Cristina Iglesias

Patricia Falguières (ed.), Cristina Iglesias, exh. cat., Carré d’Art, Nîmes (11 March – 12 June 2000), Nîmes/Arles, Carré d’Art/Actes Sud, 2000

Cristina Iglesias, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 2003

→Cristina Iglesias, Drei hängende Korridore, Ludwig Museum, Cologne, 25 March–26 June 2006

→Cristina Iglesias, Musée de Grenoble, Grenoble, 23 April–31 July 2016

Spanish visual artist.

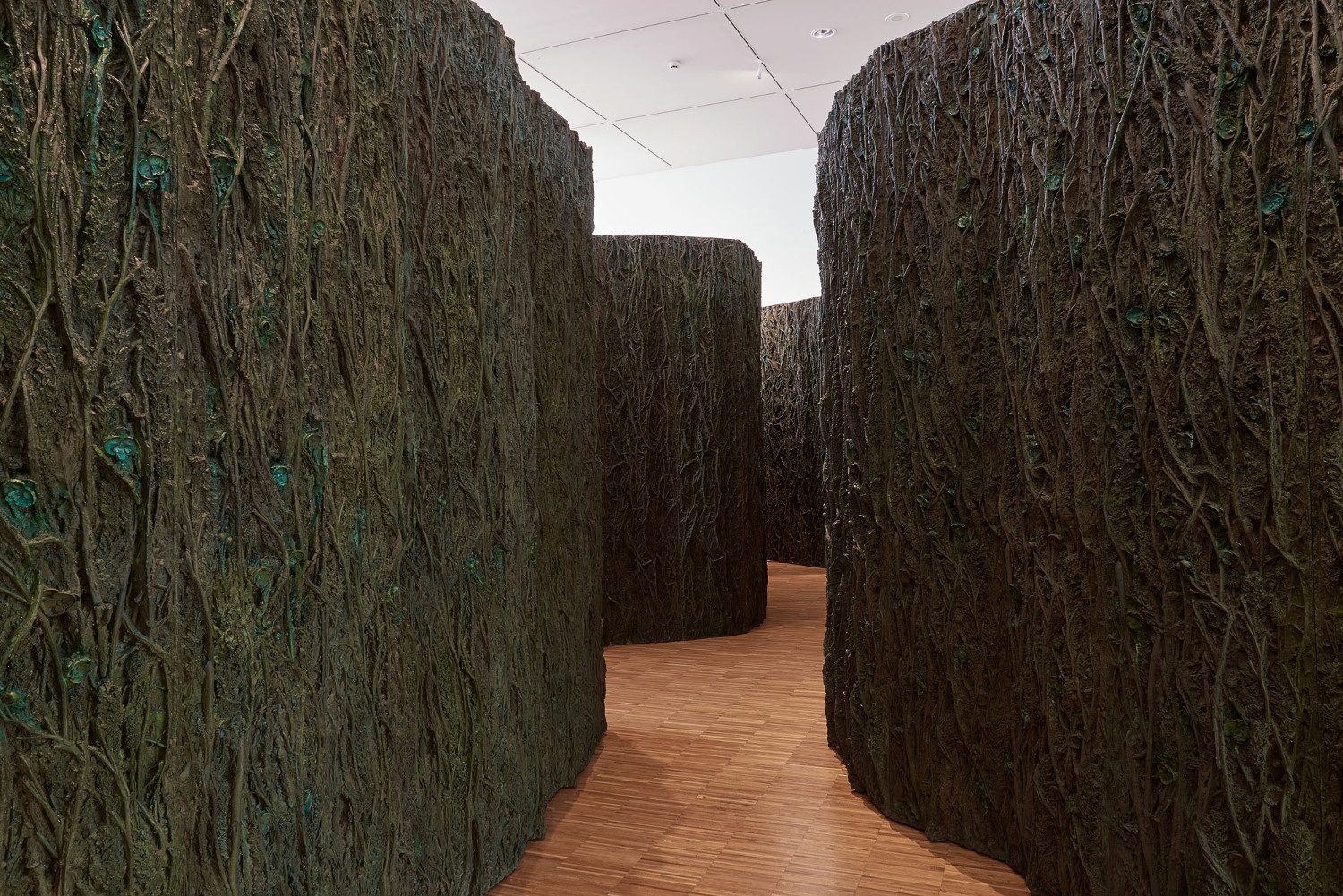

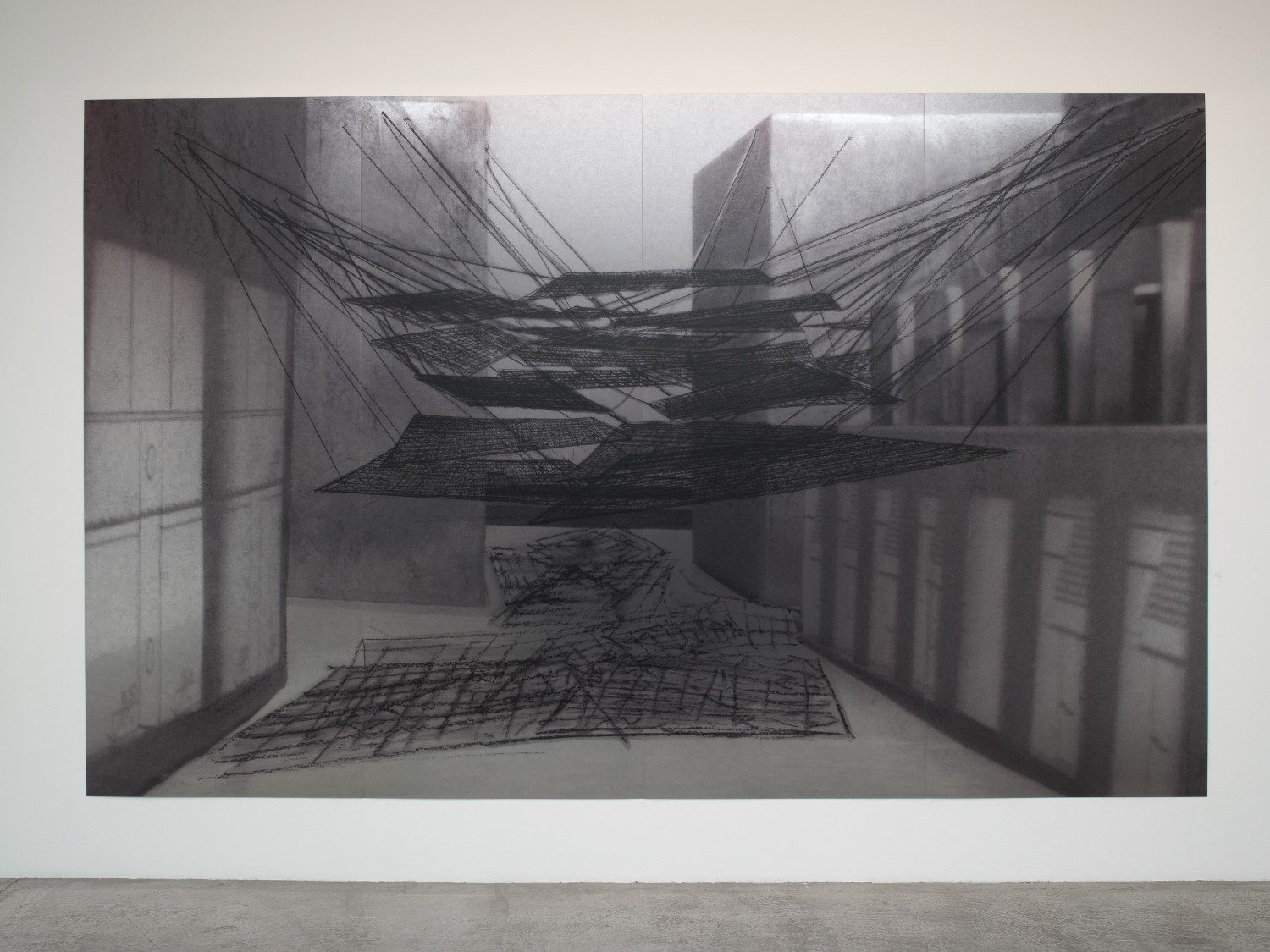

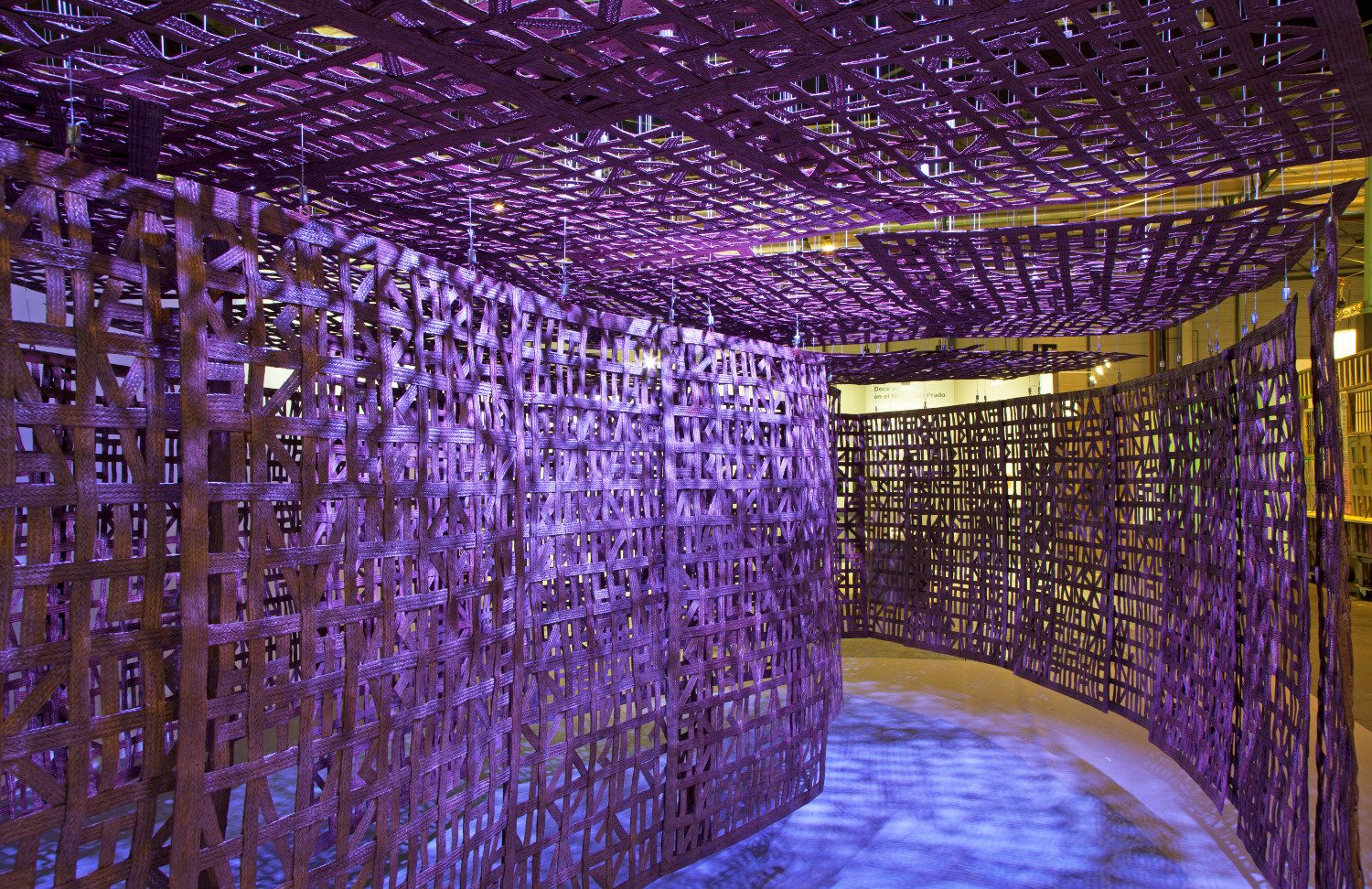

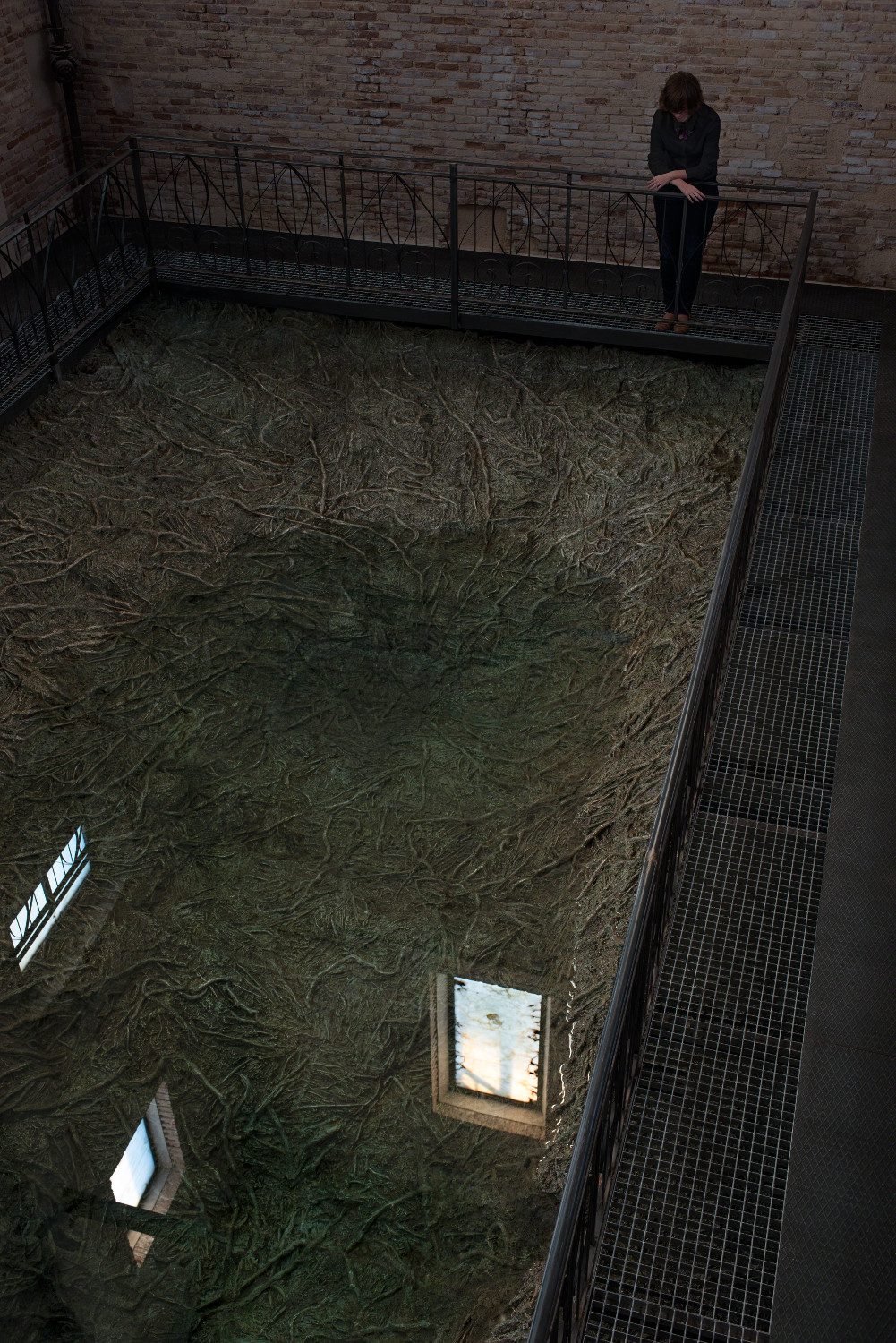

Cristina Iglesias became a figure to be reckoned with in the international art scene in the mid-1980s. After studying in London, where she discovered contemporary British sculpture, she returned to Madrid and there developed her own formal vocabulary. She is part of that generation which, in the early 1980s, re-discovered the potential of the figure, the image, the decorative and the motif, and opened up the sculptural object to its expansion in a site. By questioning the traditional space of the ‘white cube’, the artist invites spectators to enter a new and mysterious world. Interested in the poetry of various forms of matter and their immaterial traces, she questions the intrinsic nature of these bodies, and reveals both the dialogue of iron, wood, zinc, crystal and plants, and their interplay of shadows, invariably in order to subvert the rules of a geometry that is too formal. To these abstract motifs she then adds puns and words, in a fiction which the weave intermingles. In Sans titre (Celosia III, 1998), the humble materials line the space with letters forming a closed three-dimensional environment, which light first passes through and then develops its power in the environment. Raffia, sisal rope and light thus compose Sans titre (Passage II, 2002), an installation of 17 mats hanging above the visitor, with light passing through them, thus making a path of shadows and letters, which describes the descent underground of an Arab caliph, taken from a story by William Beckford. These spatial arrangements incorporate the visitor’s physical experience in an open work, and continue to deconstruct sculptural conventions: neither mass, nor substance, nor volume, nor geometry.

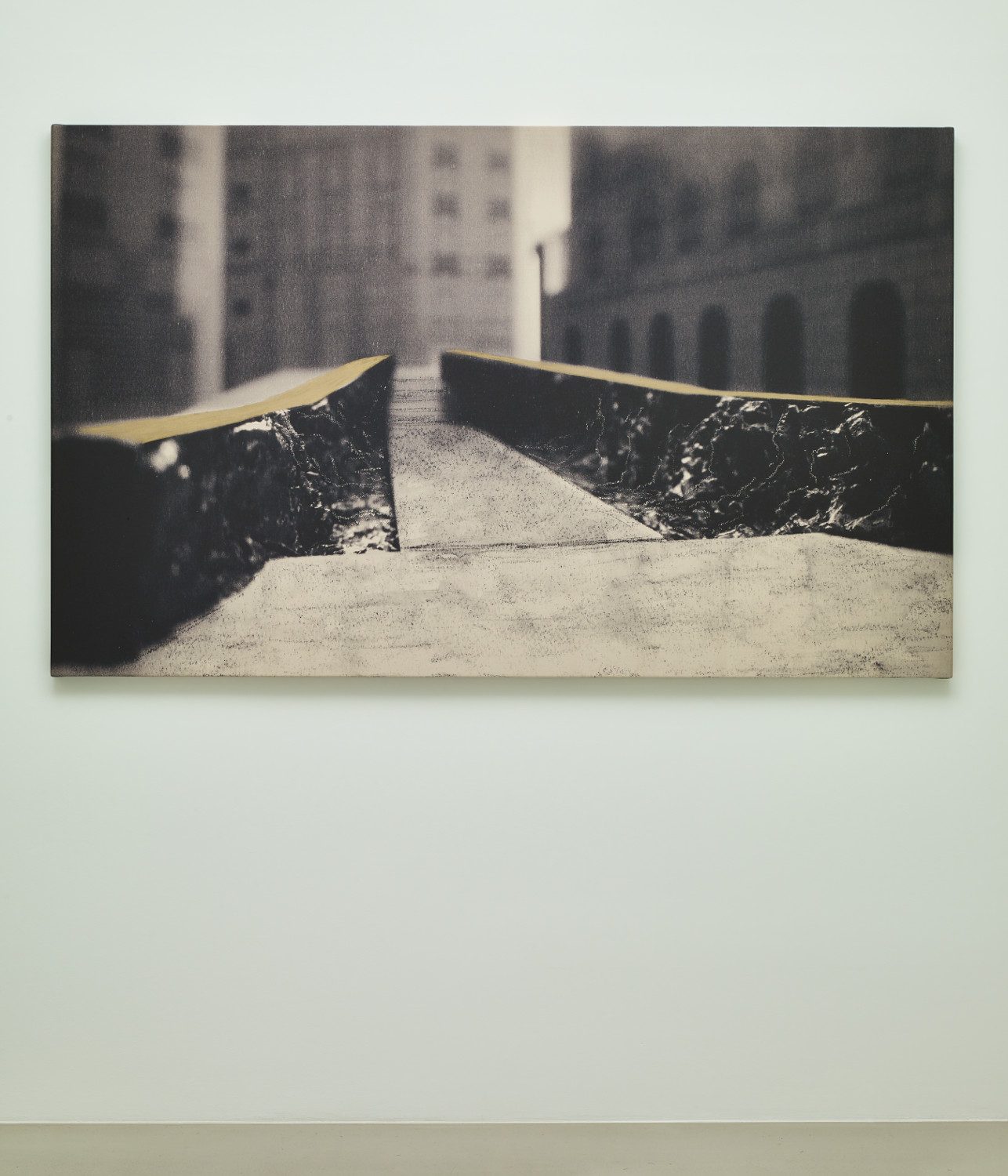

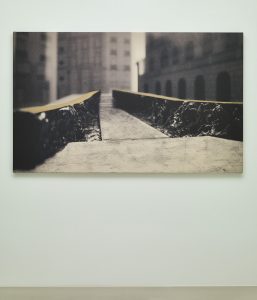

Since the early 2000s, Iglesias’s work has been incorporated in the public place, questioning the relations between the site, time, and the environment. In front of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp is installed Deep fountain (1997-2006), a large fountain in perpetual motion; when emptied, it reveals, on either side of its deep cleft, its organic and vegetal bottom, composed of cast eucalyptus leaves; when full, it reflects the museum’s façade, and duly invites the public to a visit across time. In 2006-07, the artist made the monumental bronze doors for the Prado Museum (Madrid). With Estancias sumergidas (2011), an underwater work installed in situ in the Baja California Peninsula, she carried on her research into our perception of space. On a series of concrete walls, sculpted and hollowed out by geometric motifs, she transcribed the verses of the poem Histoire naturelle et morale des Indes by José d’Acosta. Faithful to her formal and poetic vocabulary, while at the same time revealing the true nature of a place, she disguises a part of her work, through one and the same gesture. Recently, her interest in light and matter, and nature and the environment, has informed such sculptures as Pozo I and Pozo II (2011), which still pursue the same plastic and organic challenges. A natural bas-relief of vegetation and water is incorporated in the heart of the granite and bronze work, thus permitting land art to occupy the space of the ‘white cube’. Iglesias has had many solo shows, in particular at the Arnaldo Pomodoro Foundation in Milan (2009-2010), at the Pinacoteca in São Paulo (2009), at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin (2003), and at the Whitechapel Gallery in London (2003). She designed the Spanish Pavilion in Venice, for the 1986 and 1993 Biennales, and has also taken part in several group events, including the Folkstone Triennial, in the United Kingdom (2011), and the exhibition elles@centrepompidou at the Centre Georges Pompidou (2009) in Paris.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Cristina Iglesias’s Portrait

Cristina Iglesias’s Portrait