Dora Maar

Caws Marie Ann, Les vies de Dora Maar, Picasso, Bataille et les surréalistes (Dora Maar, With and Without Picasso), Paris ; London, Thames & Hudson, 2000

→Dujovne Ortiz Alicia, Dora Maar, prisonnière du regard, Grasset, Paris, 2003

→Baldassari Anne (ed.), Picasso-Dora Maar, il faisait tellement noir, exh. cat., musée Picasso (14 February – 22 May 2006), Paris, Flammarion/Réunion des musées nationaux, 2006

Dora Maar : Photographer, Dorsky Gallery, New York, 25 April – 28 June 2004

→Picasso-Dora Maar, il faisait tellement noir…, Musée Picasso, Paris, 15 February – 22 May 2006

French painter and photographer.

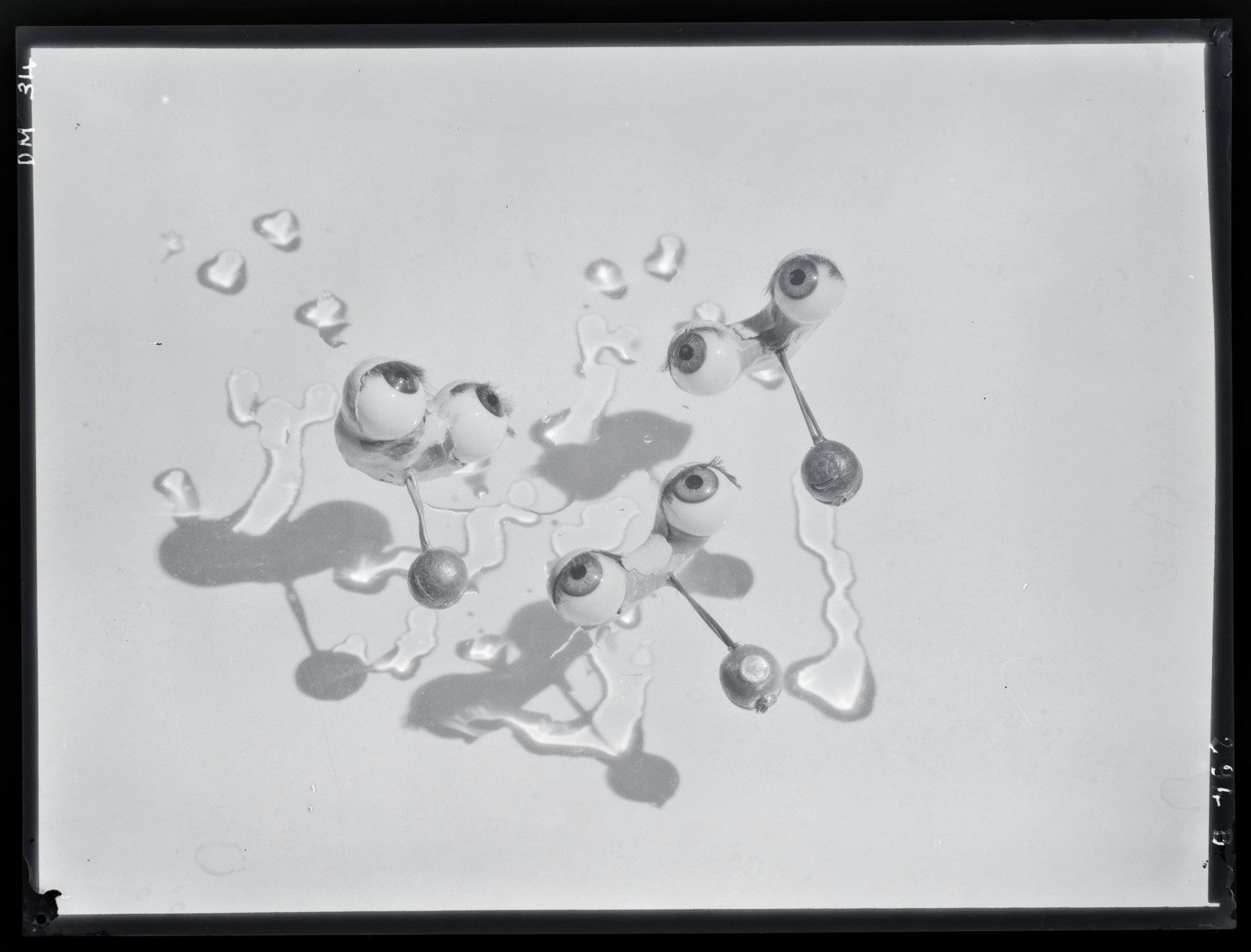

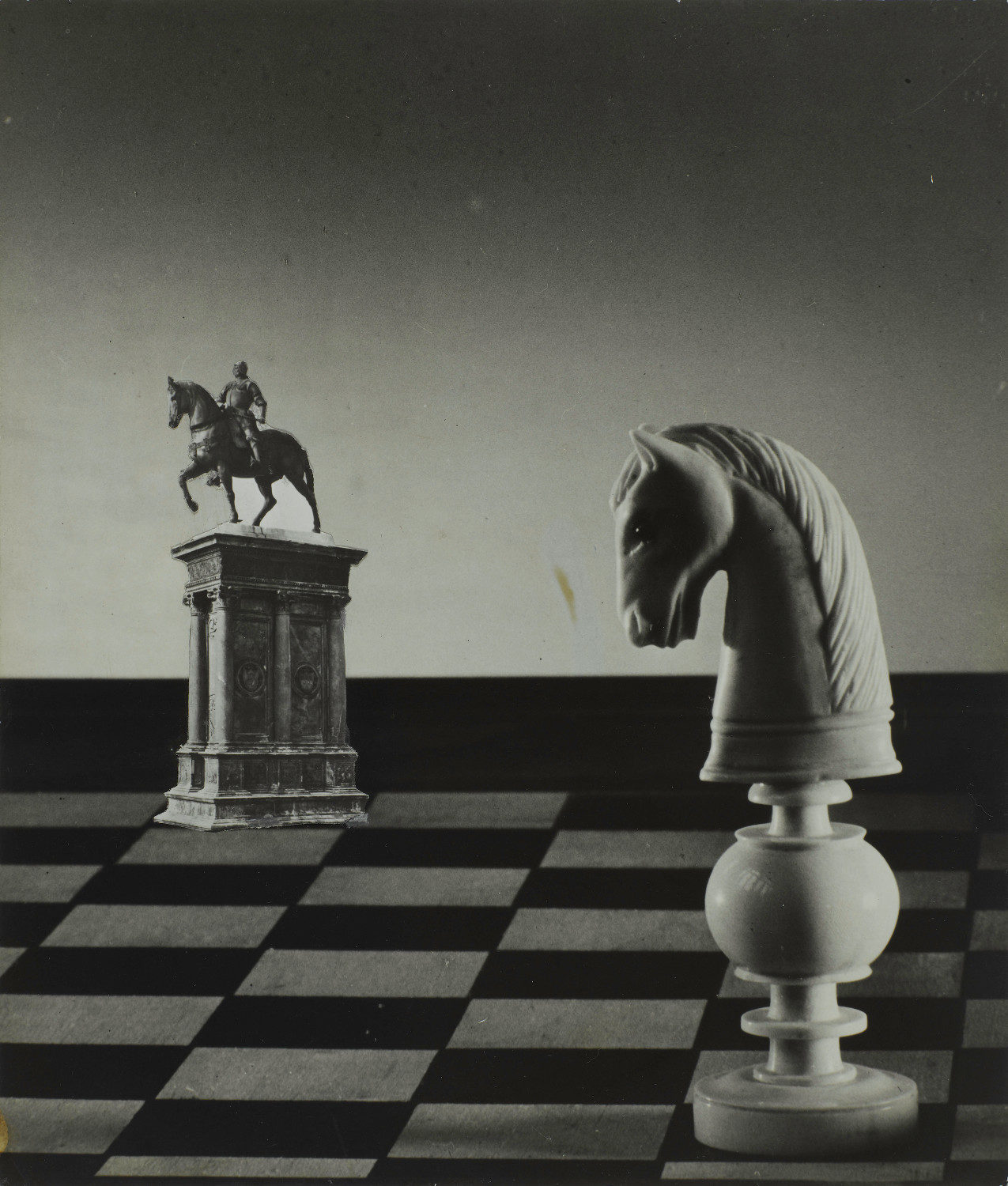

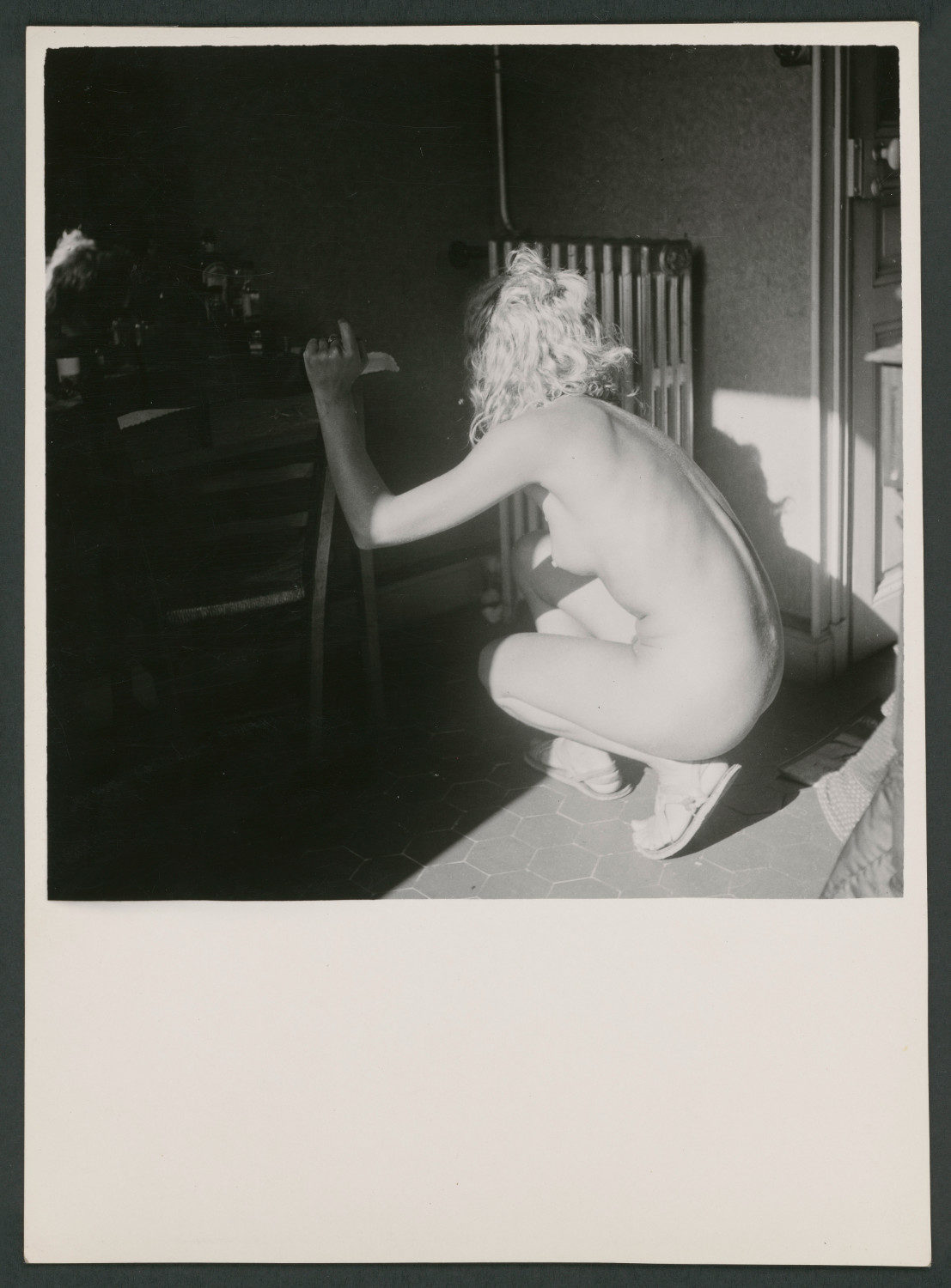

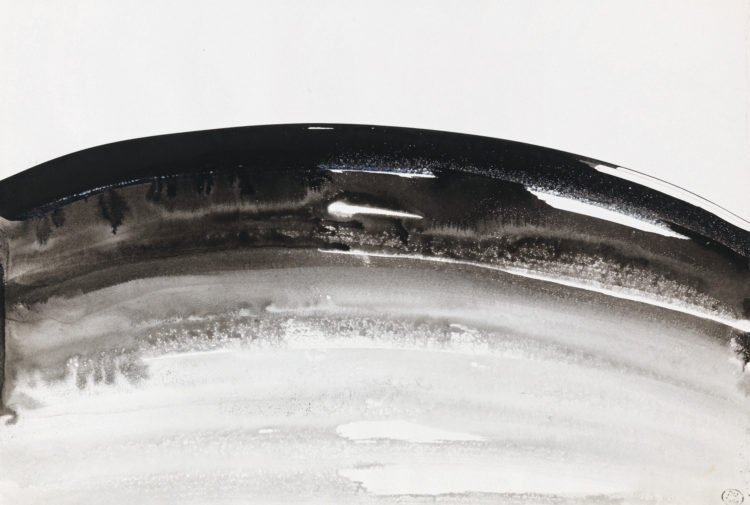

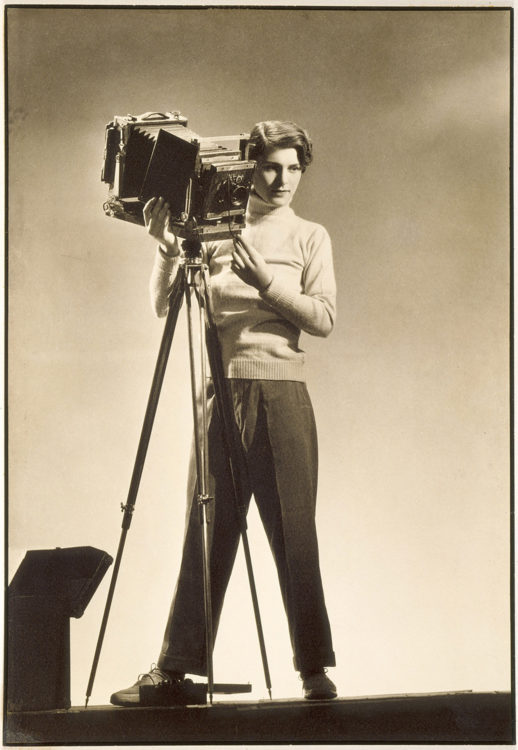

Dora Maar is mostly remembered as Picasso’s muse and lover, but his portrait of her as the Weeping Woman, bordering on madness, detracts from her singular work as a prominent photographer of the surrealist movement. Henriette Théodora Markovitch was born to a French mother and spent her early years in Argentina, where her Croatian-born father worked as an architect. When her family returned to Paris in 1926, she started taking classes at the Académie Julian and studied at the École de Photographie. In the late 1920s she shortened her name to Dora Maar and chose to focus on her photographic work, which was starting to gain recognition. Associated with Pierre Kéfer from 1930 to 1934, she collaborated in 1931 on the photographic illustration of the art historian Germain Bazin’s book Le Mont Saint-Michel (1935). She then shared a studio with Brassaï, after which Emmanuel Sougez, the spokesman for the New Photography movement, became her mentor. Her work met the aesthetic criteria of the time: close-ups of flowers and objects, and photograms in the style of Man Ray. She also took portraits, original publicity shots, and fashion and erotic photographs. In 1934, while traveling alone in Spain, Paris and London, she shot a vast number of urban views (posters, shop windows, ordinary people). Both a passionate lover and committed intellectual, she became the mistress of the filmmaker Louis Chavance and of the writer Georges Bataille, whom she met in a left-wing activist group. She signed the Contre-Attaque manifesto and rubbed shoulders with the agitprop artistic group Octobre. A close friend of Jacqueline Lamba, who became Breton’s wife, she was fully involved in the surrealist group, of whose members she made many portraits. At the height of her creativity in 1935-1936, she composed strange and bold photomontages, the most famous being 29, rue d’Astorg and The Simulator. Some of her compositions verge on eroticism, like the photomontage showing fingers crawling out of a shell and sensually digging into the sand (Untitled, 1933-1934). She also used her city photographs as backdrops for unsettling scenes: her Portrait of Ubu (1936) – in fact the picture of an armadillo foetus – conforms to the surrealists’ fascination for macabre and deformity.

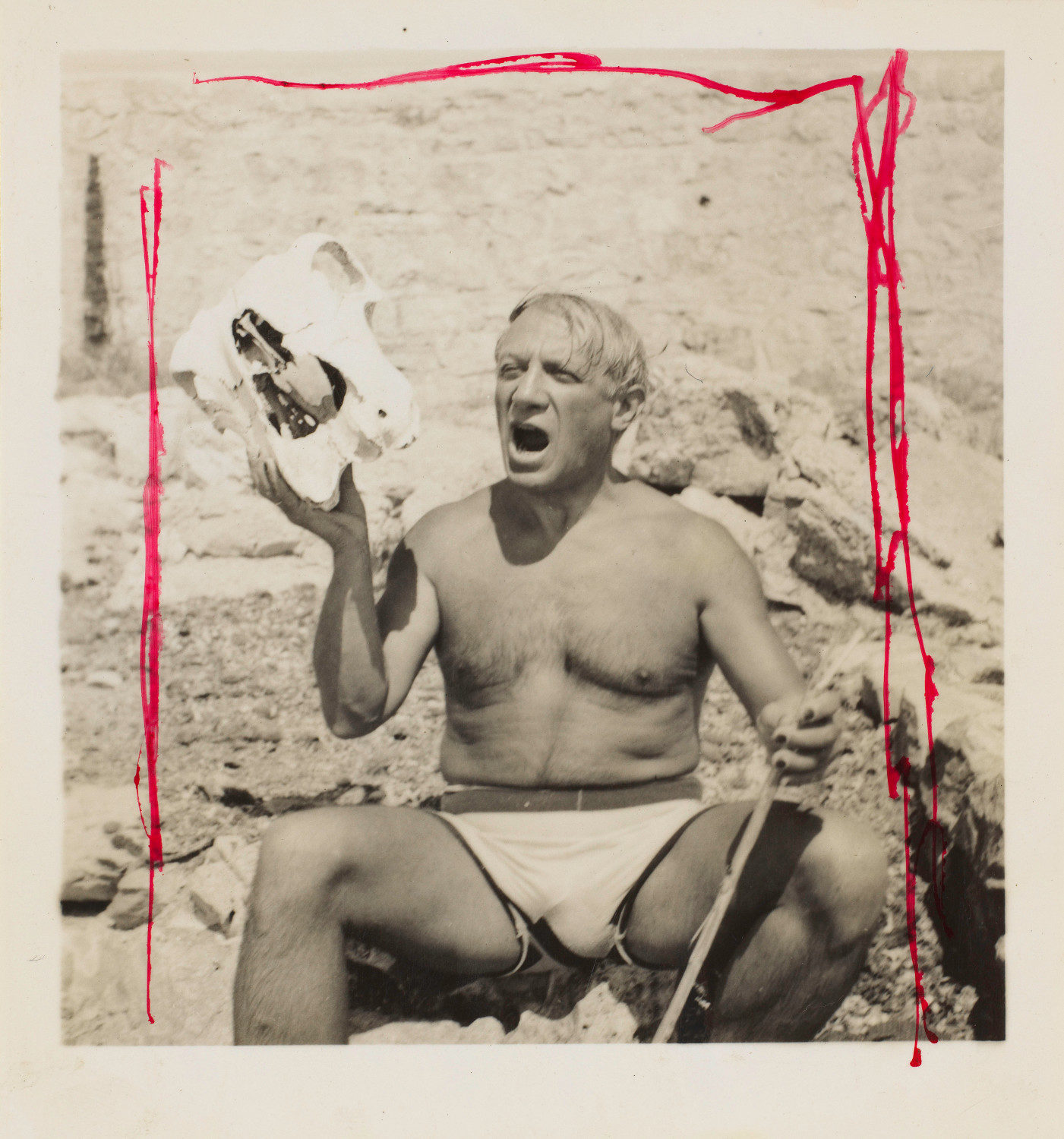

She was already an accomplished artist and nonconformist who had exhibited with the surrealists (between 1934 and 1937) when she met Picasso. According to legend, the painter noticed her while she was playing the knife game in a café in 1936. It was passion at first sight: she became Picasso’s muse, of whom he drew multiple portraits and erotic sketches. The two lovers also collaborated on a series of photograms and etchings on film. Dora Maar now owes her photographic reputation to replacing Brassaï and documenting the creative process of Guernica (May-June 1937). Encouraged by Picasso, she returned to painting and did stylised portraits in the cubist style (Portrait of Jacqueline Breton and Portrait of Pablo Picasso in the Mirror), but also very angular still lives reminiscent of the style of New Photography. By this time her fame was less a matter of her work than of her tumultuous relationship with the Spanish painter and his fascination for her as a model as he became obsessed by her, constantly depicting her as a suffering woman. When they separated for good in 1946 she suffered a severe nervous breakdown, as shown in her poems, and was treated by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Surrounded by her closest friends, she increasingly retired into mysticism and spent part of her late years as a recluse. The engravings and paintings she made during this period are in stark contrast with the rest of her work: devastated, austere, and almost abstract landscapes of a romantic Provence. She made a brief return to photography in the 80s, reprising the technique of the photogram. She also made regular additions to her poetry notebook, which she called “a secret that remains a secret even to myself,” until her death. The only exhibition of her work as a photographer in her lifetime was held in Valencia, Spain, in 1995.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Dora Maar under the spotlights

Dora Maar under the spotlights  Dora Maar despite Picasso

Dora Maar despite Picasso