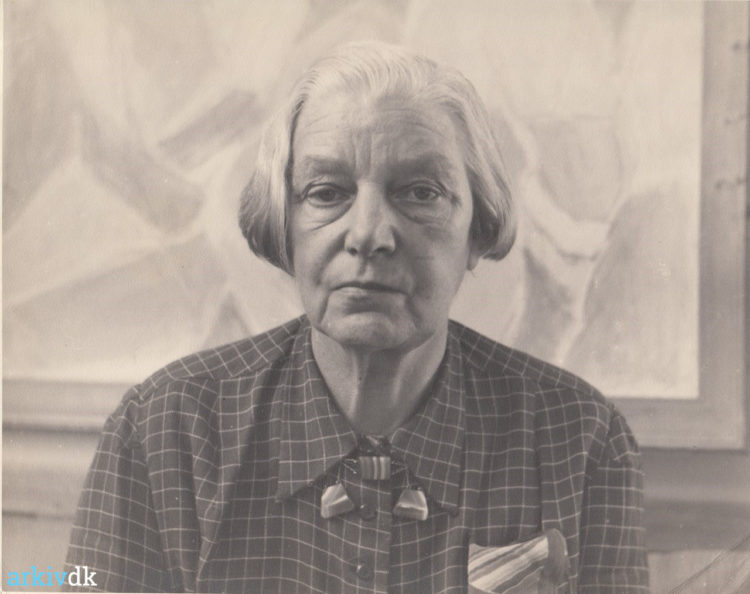

Emily Carr

Shasbolt Doris, The Art of Emily Carr, New York, Douglas & McIntyre, 1987

→Lamoureux Johanne & Thom Ian M. (ed.), Emily Carr: New Perspectives On a Canadian Icon, exh. cat., National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Vancouver Art Gallery; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Museum of Fine Art, Montreal; Glenbow Museum, Calgary (2006–2008), Ottawa, National Gallery of Canada/Vancouver, Douglas/McIntyre, Vancouver Art Gallery, 2006

→Jensen Phyllis Marie, Artist Emily Carr and the Spirit of the Land: A Jungian Portrait, London/New York, Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2016

Emily Carr in France, Vancouvert Art Galley, 22 June–22 September 1991

→Emily Carr: New Perspectives, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 2 June–4 September 2006

Canadian painter.

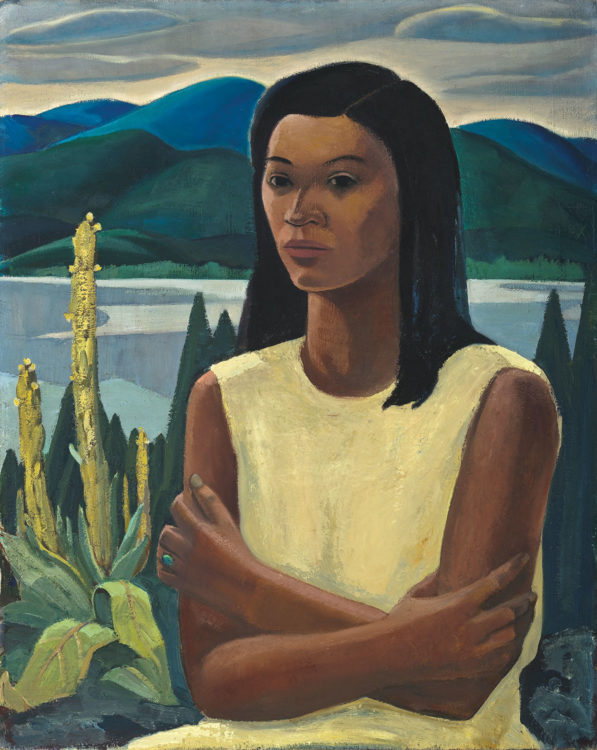

An orphan at the age of 17, Emily Carr moved to San Francisco with the consent of her guardians to join the California School of Design. The drawings she made during a visit to the Ucluelet Presbyterian mission prefigured the great project that would drive her whole work: to paint the great Canadian landscapes and depict native heritage, like the Squamish reservation near Vancouver. Her encounter with native monumental sculptures – totem poles – during a trip to Alaska in 1907 was decisive, as was, the next year, her stay in France, where she followed the teachings of her fellow Canadian painter Harry Phelan Gibb and of the watercolourist Frances Hodgkins. As she was introduced to Post-Impressionism and influenced by the Fauves, her style gradually departed from the codes of British tradition and became more expressive. In a time when artists took an interest in African and Oceanian motifs, E. Carr saw in them a renewal of the purely aesthetical principles of representation, rather than a thematic interest. Her painting technique changed, as can be seen in her small landscapes: economy of details, bolder outlines, newly asserted mastery of human portrayal and increased freedom of brushstrokes.

Despite her abundant production of watercolours and paintings during this period, success remained very uncertain. She spent the next fifteen years running a boarding house in Victoria. In 1927, however, her career took a turn for the best when she showed her paintings at the National Gallery of Canada with the Group of Seven, where she received the support of Lawren Harris. Upon returning to the west coast, she made a large number of paintings, the aesthetics and power of which would establish her once and for all. As her health declined, making it harder for her to work, she began to write. Her autobiographical writings achieved immediate success with a public which had previously been unappreciative of her painting.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017