Review

Yvonne McKague Housser, Marguerite Pilot of Deep River (Girl with Mulleins), ca. 1936–40, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 61 cm, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Gift of the Founders, Robert and Signe McMichael, © Estate of Yvonne McKague Housser

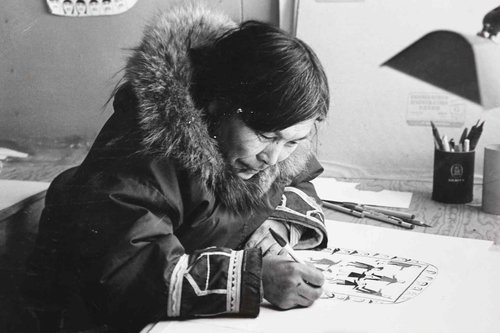

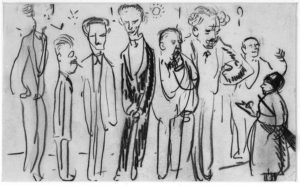

Arms folded across her chest, framed by a landscape aglow with Expressionist hues, her unblinking gaze eluding both artist and viewer – the portrait of Marguerite Pilot, an Indigenous woman painted in the late 1930s by Yvonne McKague Housser (1897-1996), exemplifies the logics of exclusion examined in the exhibition Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement. Organized by Sarah Milroy, Head Curator at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, the exhibition gathers nearly three hundred works from the interwar period, produced by women artists whose talent was stifled by the patriarchal culture that pervaded art criticism and institutions. It offers a striking contrast to the exhibition A Like Vision: The Group of Seven at 1001, which traces the development of the flagship Canadian collective from 1920 to 1933. Although they shared the friendship, pictorial experiments and in some cases the daily life of the Group of Seven members, women artists in the early twentieth century were never “invited” to join their ranks.

Arthur Lismer, Emily Carr and the Group of Seven, c. 1927, conté crayon on paper, 9.6 x 15.8 cm, Gift of The Robert and Signe McMichael Trust

They often saw their career curtailed by their lack of recognition and the domestic role that was assigned to them, at a time when their political status itself was still precarious. Canadian women were indeed granted legal personhood in 1929, and the right to vote in all provinces between 1916 and 1940—a right that was extended to all Indigenous people only in 1960. Echoing the words of Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929), S. Milroy observes that “creativity customarily requires confidence and the uninterrupted mental space in which to consolidate a vision”.2

Emily Carr, Scorned as Timber, Beloved of the Sky, 1935, oil on canvas, 112 x 68.9 cm, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, © Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

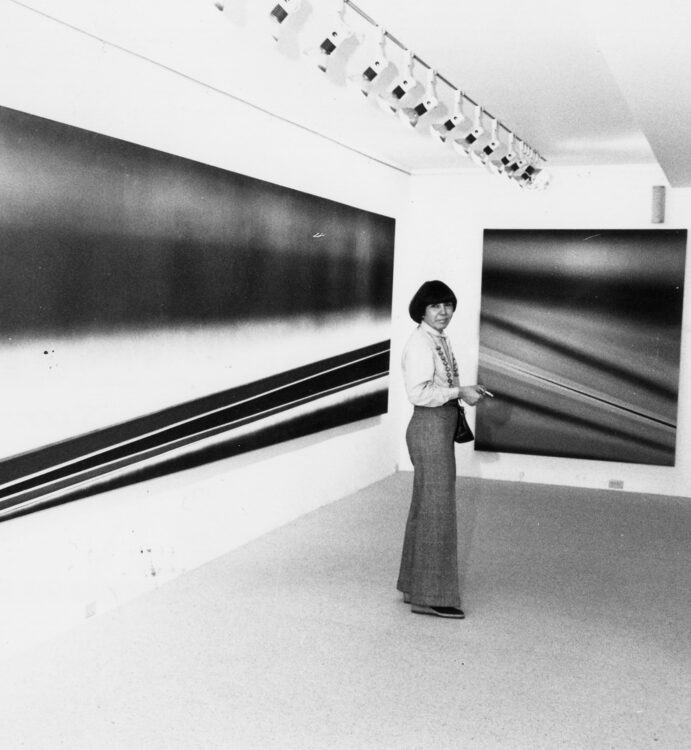

Despite, or perhaps because of the social and material hurdles they faced, the artists featured in Uninvited succeeded in developing a unique vision, both in terms of the subjects they chose and how they represented them. While the Group of Seven were concentrating on the renewal of landscape painting, perpetuating a “pioneering” spirit as they visually captured supposedly unexplored territories, their fellow female artists were expanding their palette to include urban scenes, portraits of figures marginalised by “modern” society, and natural landscapes encroached upon by fast-developing extractive industries. The trees portrayed by Emily Carr (1871-1945), still standing among freshly cut stumps, and the sketch of the mining town of Cobalt (1931) depicted by Y. McKague Housser, are arresting in their force and fragility. In contrast with the paintings by the Group of Seven, one of the striking elements in many of the works on display is the absence of an idealising or overlooking perspective. The viewpoint is at eye-level, “situated”, Donna Haraway might say, as anticipating the observation by feminist standpoint theorists that one’s gaze and knowledge are always informed by one’s position within society and its power relationships.3

Attatsiaq, Tuilik (woman’s parka) panel, 1926–1937, 65 x 38.5 cm, Manitoba Museum, Winnipeg, Collection of Winifred Petchey Marsh and Bishop Donald Marsh, © Photo: Craig Boyko

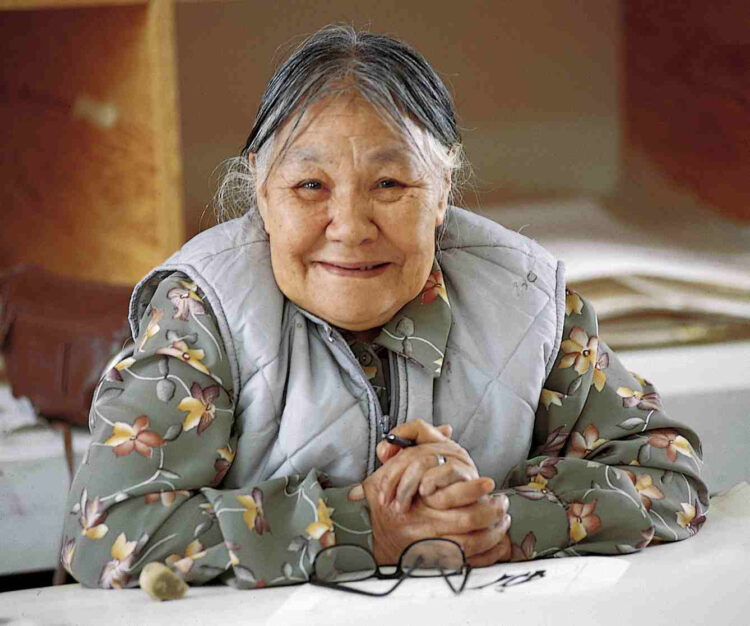

Adding to the multilayered perspectives reflected in the exhibition, S. Milroy has included the productions of Indigenous women artists such as Attatsiaq (1910-c. 1955), Elizabeth Katt Petrant (1891?-1922), Sophie Frank (1872-1939), Mrs Walking Sun and Bridget Anne Sack, whose traditional beadwork and woven baskets were becoming instrumental in their fight for economic survival as the colonial state took over their ancestral territories. By contrast, the watercolours of Winifred Petchey Marsh (1905-1995), which document the customs of Inuit women, or the landscapes of Anne Savage (1896-1971), commissioned by the Canadian government to immortalize the totem poles of the Gitxsan First Nation, reflect the “logic of reversal [that] governs relations between hosts and guests in settler-colonial contexts”.4

Yvonne McKague Housser, Sketch for “Cobalt”, ca. 1931, oil on canvas, 75 x 95 cm, Private collection, © Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid © Estate of Yvonne McKague Housser

On more than one level, Uninvited captures the tensions and paradoxes of a nation-state still under construction. To quote Paraskeva Clark (1898-1986), a Russian-born painter who immigrated to Toronto in 1933, “the process of the growth of a nation’s art is the process of the growth of the soul of a nation, of the conscience of that nation”.5 Although a growing number of institutions now recognise that this process could not be achieved without over half the soul of a society, the reparative work needed to redress centuries of exclusion is still in its infancy.

A Like Vision: The Group of Seven at 100, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, 25 January 2020-August 2022.

2

Milroy, Sarah (ed.) “Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement”, in Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement, exh. cat., Vancouver, Berkeley, Figure 1, 2021, p. 18.

3

Haraway, Donna, « Savoirs situés : la question de la science dans le féminisme et le privilège de la perspective partielle », in Semians, Cyborg, and Women, New York, Informa, Routledge, 1991. See also Smith Dorothy E., “Women’s Perspective as a Radical Critique of Sociology” (1974), in Harding Sandra (ed.), The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader: Intellectual & Political Controversies, New York, Routledge, 2004.

4

Huneault, Kristina, “The Politics of Invitation: Canadian Women’s Art History and the Settler-Colonial Context”, in Milroy, Uninvited, p.28.

5

Clark, Paraskeva, cited in Milroy, “Uninvited”, p. 1.

Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement, from 10 September 2021 to 16 January 2022, at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario. The exhibition will continue at the Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta from 19 February to 8 May and then at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Winnipeg, Manitoba from 18 June 2022 to 3 January 2023.

Garance Malivel, "Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Movement." In , . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/uninvited-les-artistes-canadiennes-de-la-modernite/. Accessed 1 July 2025