Eva Aeppli

Berthon Jacques, The astrological sculptures of Eva Aeppli, Omaha, Old Market Press, 1983

→Eva Aeppli, exh. cat., Moderna Museet, Stockholm (24 April – 13 June 1993), Stockholm, Moderna Museet, 1993

Eva Aeppli, Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, 16 September 1994 – 15 January 1995

→Eva Aeppli, Museum Tinguely, Basel, 25 January – 2 May 2006

→Eva Aeppli, Museum Tinguely, Basel, 6 June – 1 November 2015

Swiss painter and sculptor.

Eva Aeppli studied painting, engraving and sculpture at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Basel. At the age of 16 she learned of the existence of concentration camps while reading Die Moorsoldaten (Peat Bog Soldiers, 1935) by Wolfgang Langhoff. This song had a long-lasting effect on her work. In 1951, she married Jean Tinguely. “I was scared that his art would suffocate me. That is why I did not want to see any of his works, nor did I want to let myself be influenced by him,” she stated. Her independence from her husband had no equivalent, considering what she exhibited with regard to art in general, fashions, trends and means of recognition. E. Aeppli defended the amateur and totally individual characteristics of her art, expressed herself rarely, and was recognised quite late and sporadically by the institutions of her time. Nevertheless, she had an enormous influence on the work of J. Tinguely’s second wife, Niki de Saint Phalle, who in 1963 temporarily named her the physical and spiritual manager of her work in the event of the sculptor’s death. In 1952, E. Aeppli moved to Paris with her husband and created marionettes that she sold in toy stores to pay their rent. They lived miserably. Helped by Daniel Spoerri, they moved into a modest studio in the famous Impasse Ronsin.

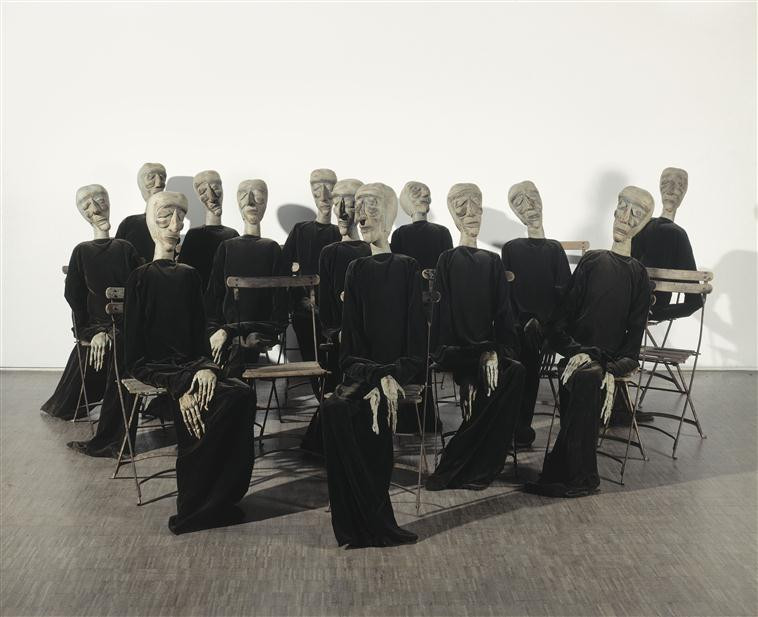

Between 1953 and 1957, it was she who provided for the household. J. Tinguely always gave her this role of leader and supporter, having previously encouraged her to become an artist, and to move from charcoal to oil painting. In 1960, they separated and she dedicated herself to large format paintings in which stacked skeletal characters and skulls define compositions on the limit of abstraction, and contemporary danses macabres represent death and a dominating pessimism. She progressively turned towards a more sculptural body of work, one of the first signed by a woman in the 1960s and 1970s (alongside Germaine Richier and Barbara Hepworth). Mostly made up of stitched, mute and solitary fabrics as if seized with pain and fright, the characters are treated with a great economy of means: they are monochrome, of undefined gender, with the same pale face, skeletal body with dangling arms and puny legs. The artist herself called these “Maccabees”. Certain groups of these fabric mannequins are considered her masterpieces today: La Table (1967); Groupe de 13 (hommage à Amnesty international) (1968). Her works address frontally the victims of the century, from the deported to the victims of torture. The gaze is dark with no escape, as she explained to a critic who reportedly misunderstood La Table, “You are wrong to assume that I put death at the centre of the table to convey a message of despair contrary to Jesus’s message of hope. On the contrary, my work was a commentary on the fact that people feel abandoned, they are consumed by the fear of death, they refuse the gift of eternal life from the centre that Jesus should represent. I hope that through their expressions we can see the isolation of these figures at the table, imprisoned in their negative world,” (Eva a Myth?, 2000).

From the mid-1970s, the fabric mannequins were replaced by bronze, individual figures and a series of monumental busts made in velour, cotton and leather stuffed with kapok, most of which were dedicated to astrology: Les Planètes (1974–1976) followed by Le Zodiaque (1979–1980). In 1991, the couple created a series of works exhibited at the Musée de l’Hôtel-Dieu in Mantes-la-Jolie in 2002. This collaborative work as well as the relationships that E. Aeppli had with major artists of her time are “exhibited” in her books Livres de vie, a wordless autobiography that she kept for fifty years (1954–2002). In them, she collected letters, manuscripts, drawings, images, photographs sent by friends, and reproductions of her works. Life and artistic creation came together to form an indivisible entity, all the more unique and useful as E. Aeppli always refused to comment on her creations. This photo journal is also an image of post-war Europe. The 1994 retrospective dedicated to her work in Bonn was followed by others at the Garden of the Zodiac in Omaha, Nebraska in 2000 and later at the Musée Tinguely in Basel in 2006.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019