Florine Stettheimer

Tyler Parker, Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1963

→Bloemink Barbara J., The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995

→Muhling, Matthias (dir.), Florine Stettheimer, exh. cat., Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich (27 September 2014 – 4 Janvier 2015), Munich, Lenbachhaus/Hirmer, 2014

Florine Stettheimer, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1946

→Florine Stettheimer: Still Lifes, Portraits and Pageants, 1910–1942, Institut d’art contemporain, Boston, 1980

→Florine Stettheimer: painting poetry, Jewish Museum, New York, 2017

American painter.

Born to a wealthy German Jewish family, Florine Stettheimer never needed to sell her painting to make a living. From 1892 to 1895 she studied at the Art Student League in New York under the supervision of the painter and illustrator Kenyon Cox and of Robert Henri. She was a great admirer of the work of John Singer Sargent, and started painting portraits and still lives, which revealed her will to do well rather than her genuine talent. In 1906, she followed her mother and two sisters Ettie and Carrie to Europe where they lived for several years. There, she studied at art academies in Berlin, Munich and Stuttgart, discovered the symbolism of Gustav Klimt and Ferdinand Hodler, became familiar with the works of the Impressionists, Nabis and Fauves, and visited the 1909 Venice Biennale. Upon returning to the United States in 1914, the sisters opened a salon, which quickly became a hub of the artistic avant-garde. Marcel Duchamp, the painters Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth, the photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, the art critic Henry McBride and the writer Carl Van Vechten all attended the soirees at the Stetties’, as they were known at the time. Florine painted, Ettie wrote novels using the pen name Henrie Waste, and Carrie spent her time building a doll’s house that even contained an art gallery showing reproductions of works by M. Duchamp (Nude Descending a Staircase), Elie Nadelman, Gaston Lachaise and Alexander Archipenko, made by the artists themselves (1916-1944, Museum of the City of New York).

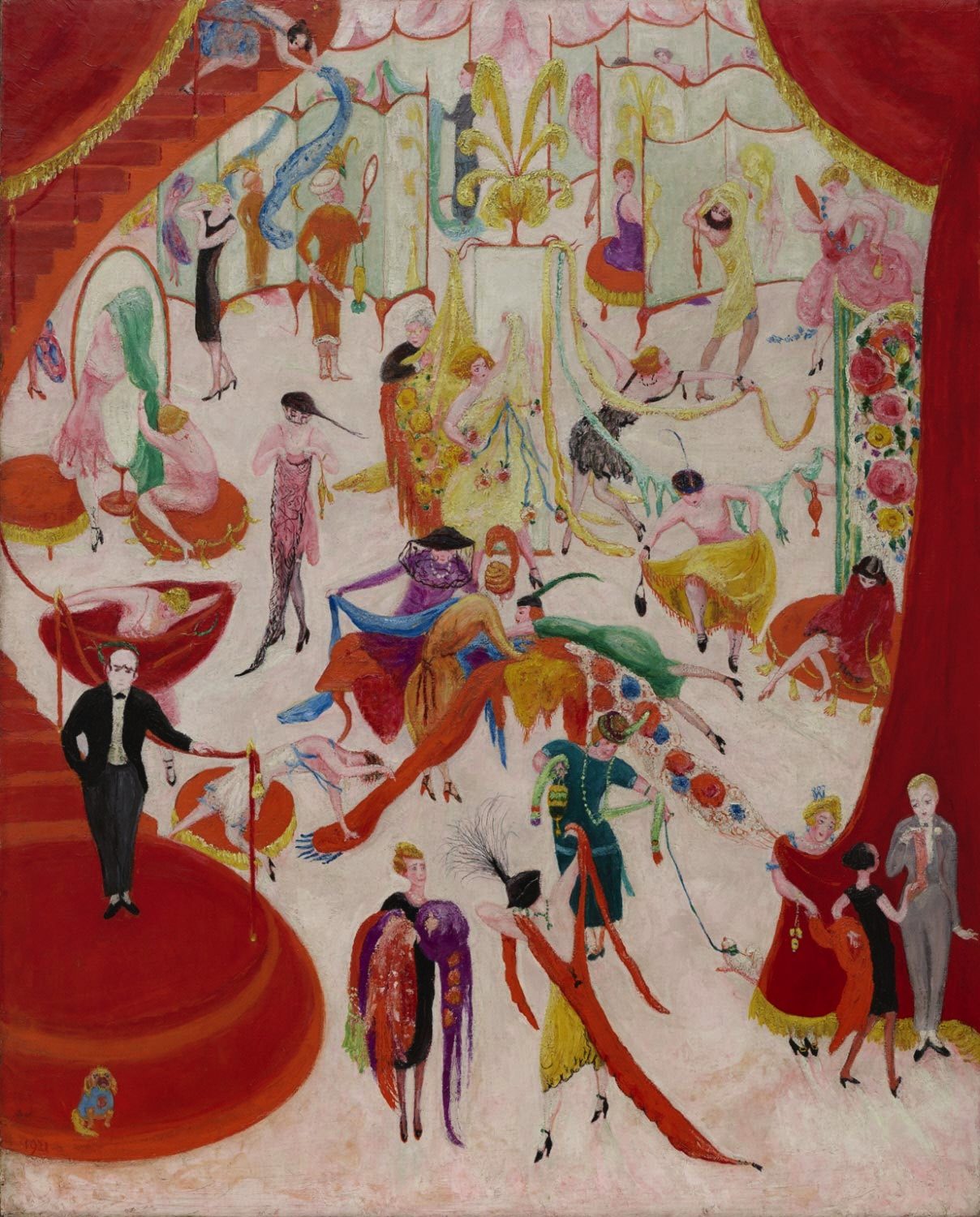

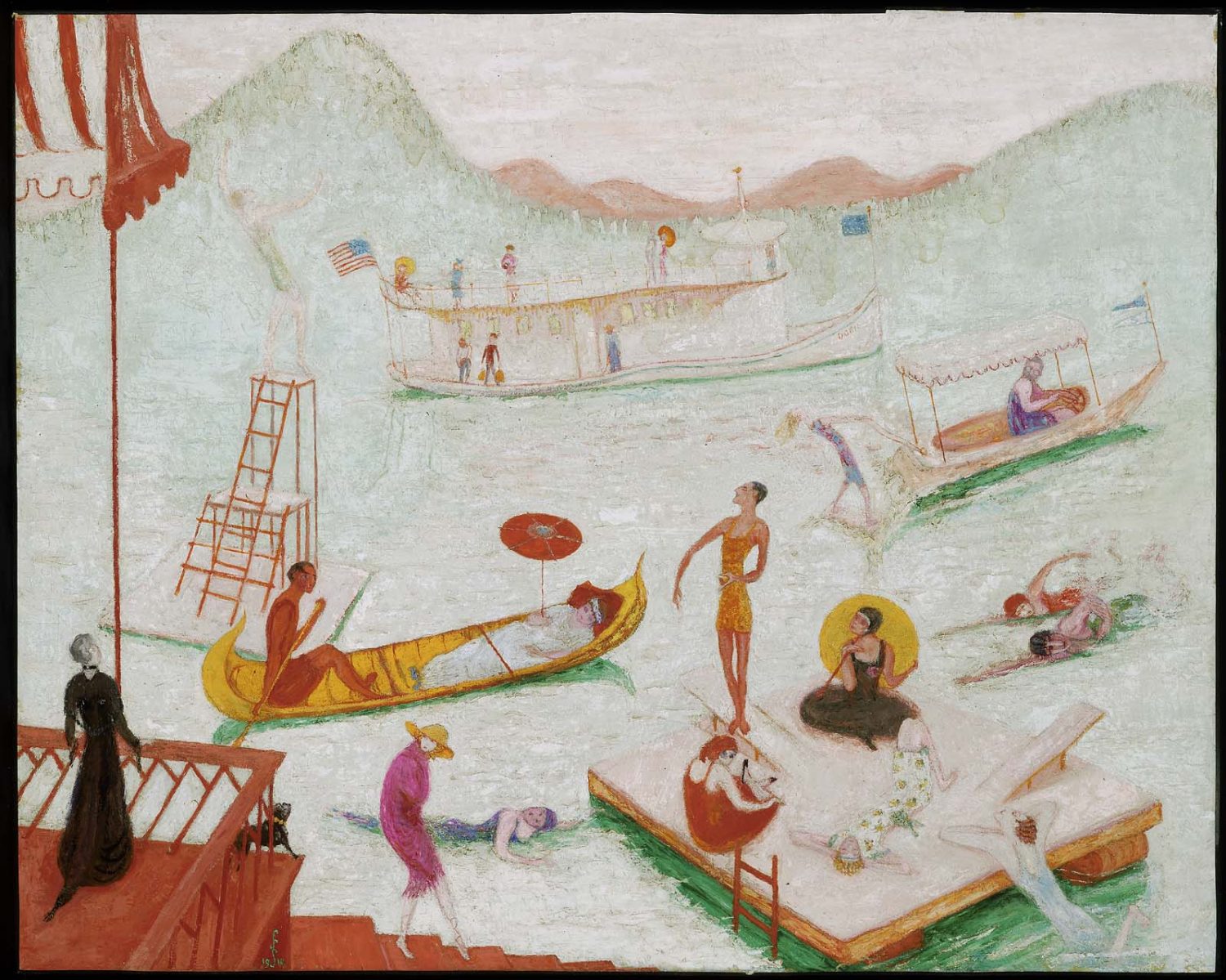

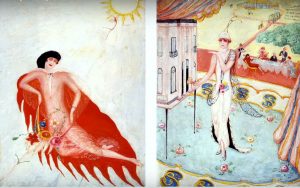

After the failure of her only personal exhibition at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1916, F. Stettheimer strove to find her own distinctive style. During the soirees she hosted, she made sketches of the guests, then used their silhouettes in large compositions that she called, as a nod to a historic genre of English painting, conversation pieces, such as Soiree and Studio Party, New Haven, Yale University, 1917-1919). She depicted her characters flattened, with singular perspectives and increasingly bold colours, finally settling for her own original style in the early 1920s. Despite being influenced by new movements, her style, which combined false naivety and sophistication, remains in a class of its own. She painted the world around her, made portraits of her mother, her sisters, her friends – M. Duchamp and C. Van Vechten. She sought to represent, with an ever-ironical eye, the leisure of the New York upper classes (Beauty Contest, Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1924). Some of her works bear more socially conscious characteristics, such as Asbury Park South (Nashville, Fisk University, 1920), which shows a black-only beach in New Jersey.

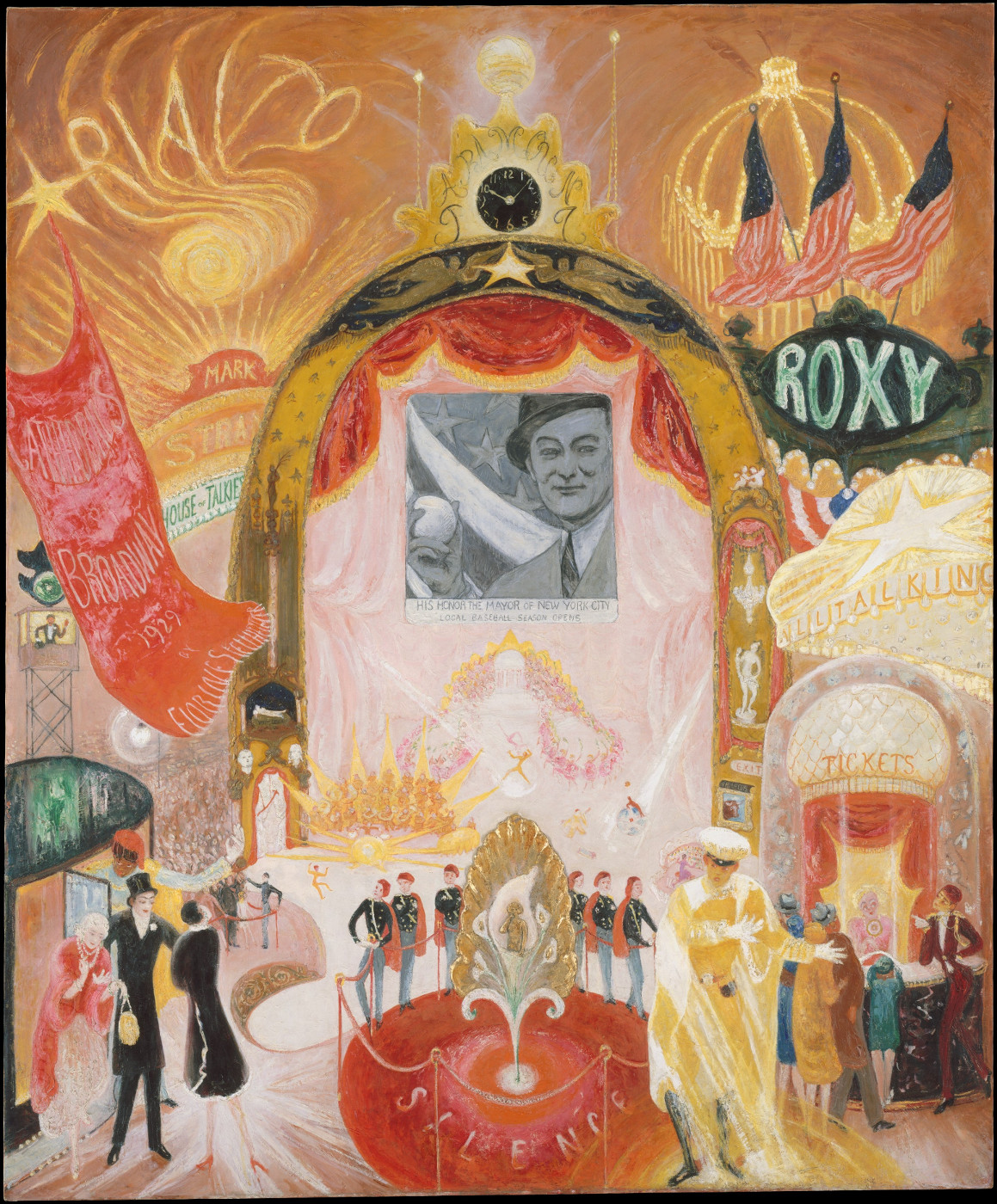

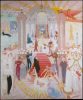

The only public success she enjoyed during her lifetime came in 1934 with the sets and costumes she designed for Virgil Thompson’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts with a libretto by Gertrude Stein, which was a great success at the Wadsworth Atheneum Theatre on Broadway. However, her major – if not best-known – work is the Cathedrals series, which she painted between 1929 and 1942 (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art). In this series, she celebrates her hometown of New York and its pillars – leisure, power, money and art – while also making an amused satire of it. In 1935, she set up her studio in the very fashionable Beaux-Arts Building across from Bryant Park. She continued painting and entertaining, making her life a reflection of her art. A retrospective exhibition was held at the Whitney Museum of American Art of New York two years after her death. Her work was repopularised by feminist studies of the 1980s, and the painter is now considered as one of the first representatives of camp aesthetics as defined by Susan Sontag (“Notes on Camp”, in Partisan Review, 1964) – a deliberately kitsch, artificial and excessive form of art.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Art History Today | Florine Stettheimer

Art History Today | Florine Stettheimer