Frances Hodgkins

Gill Linda, Letters of Frances Hodgkins, Auckland, Auckland University Press, 1933

→Buchanan Ian, Dunn Michael, Eastmond Elizabeth (ed.), Frances Hodgkins : Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat., Auckland Art Gallery (1994), Auckland, Auckland University Press, 2001

→Drayton Joanne, Frances Hodgkins : A private Viewing, Auckland, Godwit, 2005

Frances Hodgkins 1869 – 1947 : A centenary exhibition, Commonwealth Institute Gallery, London, 1 – 28 February 1970

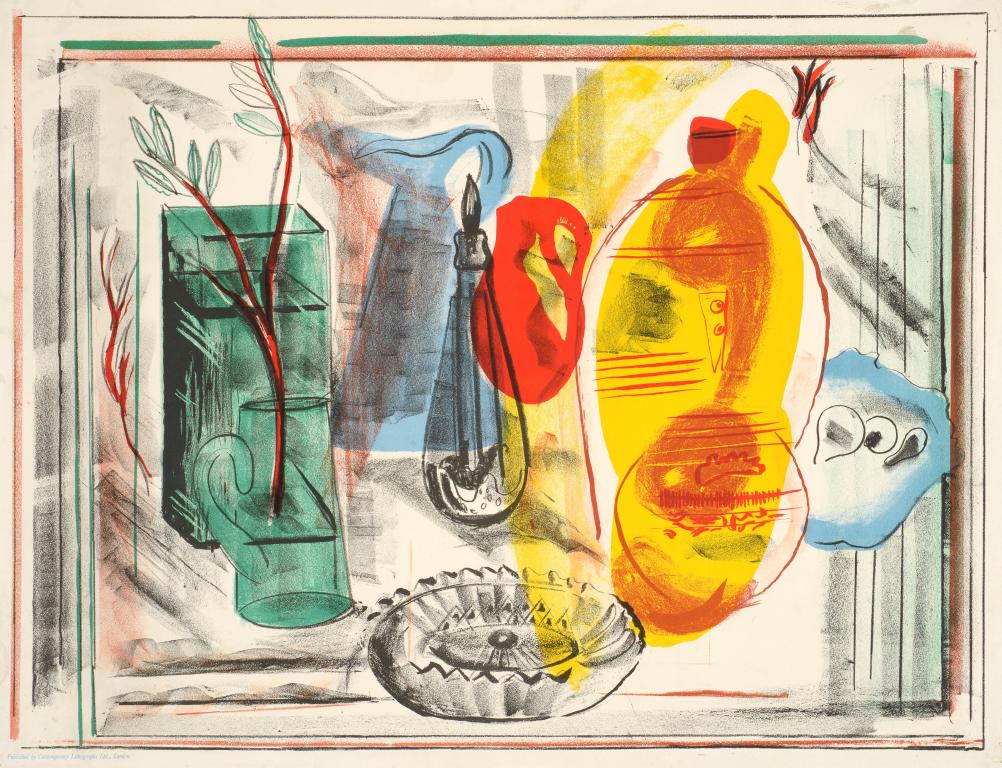

→Frances Hodgkins : Forgotten Still Life, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, 22 August 2015 – 31 July 2016

→An Emerging Talent: Early Works by Frances Hodgkins, Mahara Gallery, Waikanae, 9 April – 4 June 2017

New Zealand painter.

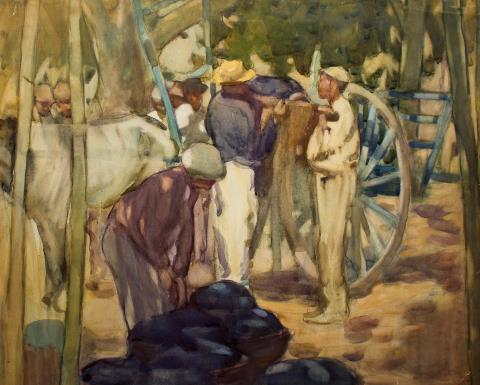

Along with her older sister Isabel, Frances Hodgkins was taught watercolour technique by her father, a lawyer who had emigrated to New Zealand and a renowned amateur watercolourist of landscapes in the tradition of William Turner. While Isabel, who initially encountered more success than her younger sister, took after her father in terms of painting style, her sister preferred to focus on the study of the human form. The watercolour classes of the recently emigrated Italian Girolamo Pieri Nerli helped her in this regard. His influence is visible in artworks such as Girl With the Flaxen Hair (Museum of New Zealand Te Papa, Wellington, 1893). In 1895-1896, she also frequented the Dunedin School of Art. Her art of the time juxtaposed scenes from the rural life around her, which she treated with a rather sugary realism (Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki: Washing Day, circa 1895; At the Pump, 1901). Having exhausted the educational possibilities in the British colony, the young painter managed to save enough money for a trip to Europe, where she notably took sketching classes with Norman Garstin in Normandy, during the summers of 1901 and 1902. On her return to New Zealand in 1903, she opened a studio in Wellington. Her work was therefore clearly influenced by the European movements, particularly Impressionism. In Paris, in 1908, she became the first female professor at the Colarossi Academy. She taught watercolours there, before starting her own school. By the time she returned to the Southern hemisphere, in 1912-1913, Australia reserved a hero’s welcome for her, seeing her as the epitome of modernity.

During World War I, her move to St Ives, in Cornwall, where she met many young artists such as Cedric Morris or Arthur Lett-Haines, was to mark a major turning point; setting aside her watercolours, she began to produce large oil paintings, and Post-Impressionism now played an essential role in her work: in Loveday and Ann: Two Women With a Basket of Flowers (Tate Modern, London, 1915) or in The Edwardians (Auckland Art Gallery, circa 1918), the decorative effects and textures of an intimist interior imply the influence of Pierre Bonnard or Édouard Vuillard. Despite a number of exhibitions, she only rarely managed to sell her work and was obliged to work as a graphic designer for the Calico Printers’ Association in Manchester. Success came before 1930, concomitant with one last stylistic evolution. In 1929, she became a member of the Seven and Five Society, a modernist group led by Ben Nicholson and to which the sculptor Barbara Hepworth and Roger Moore also belonged, twenty years younger than herself. After a first solo exhibition at the Claridge Gallery of London in 1928, the zenith of her career came with an exhibition at the St Georges Gallery in 1930. That year, she signed a contract with London art dealer Arthur R. Howell. Over sixty at the time, the New Zealand-born artist thus became one of the emblematic figures of British modernism. Her art was very colourful, with an increasingly free approach to form and line. She stood out particularly through her research into the theme of still life-landscape, exploring all possibilities emerging from the confrontation of these two genres, as in Wings Over Water (Tate Modern, London, 1930), in which three shells were placed in front of an open window before a coastal landscape. It was also in the form of still life that she chose to represent herself in Self-portrait: Still Life (Auckland Art Gallery, circa 1935), in which various objects symbolise her presence. The 1940s saw the artist turn gradually towards abstraction. However, the war drained her physically and psychologically and she was eventually admitted to a psychiatric hospital, where she was to live out her days.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

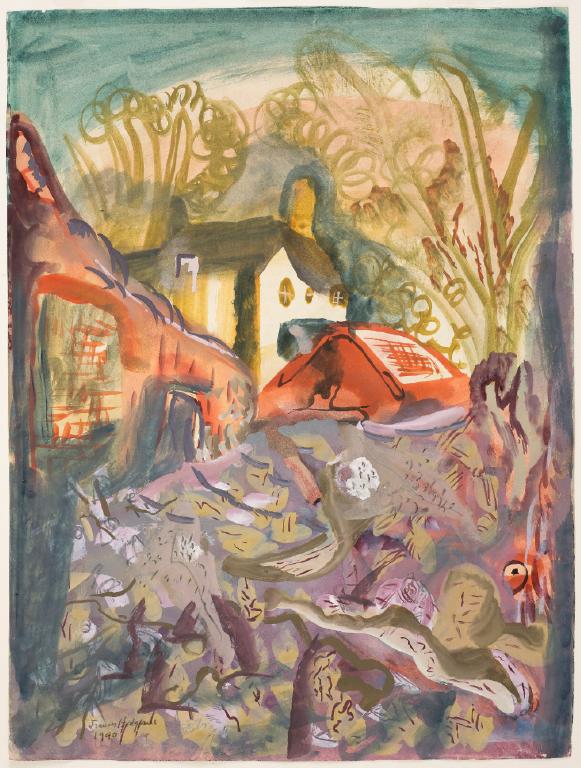

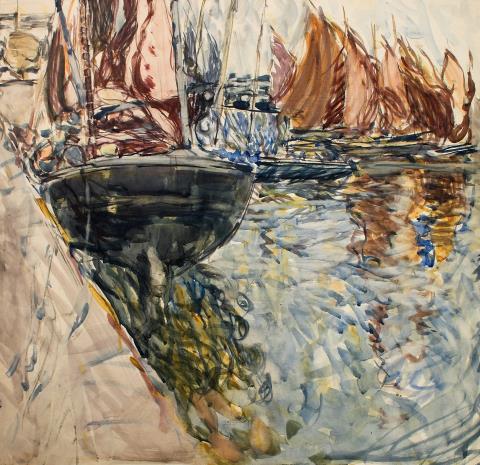

Kimmeridge Foreshore by Frances Hodgkins

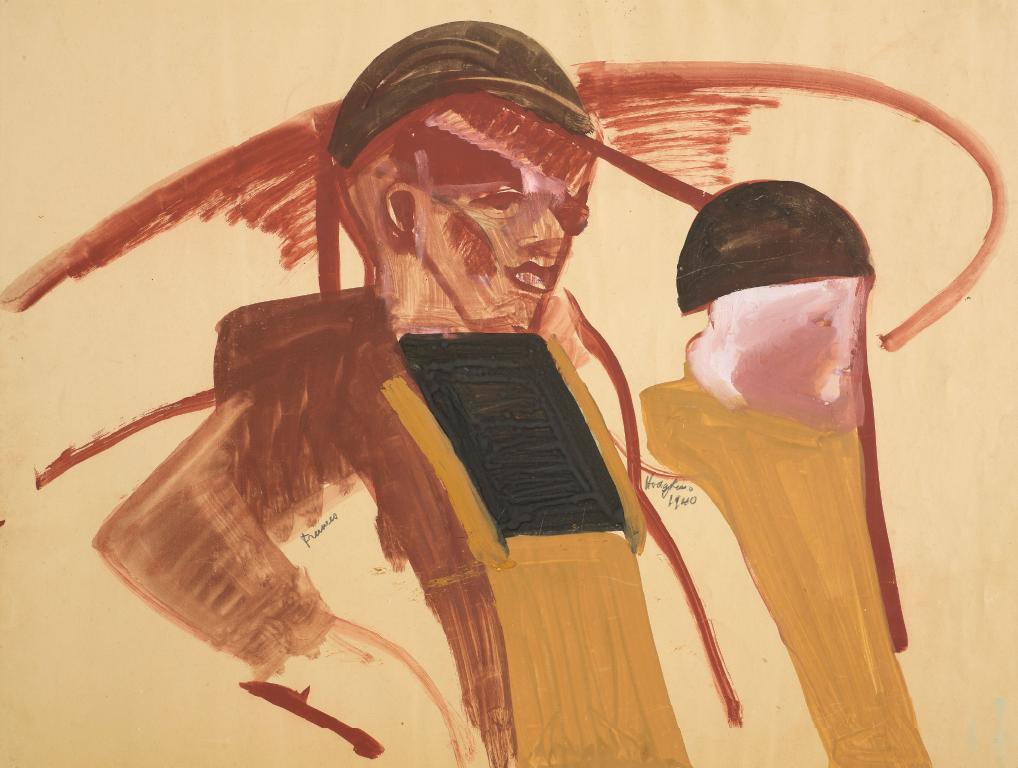

Kimmeridge Foreshore by Frances Hodgkins  Zipp by Frances Hodgkins

Zipp by Frances Hodgkins