Françoise Vergier

Nadeije Laneyrie-Dagen (ed.), Le Paysage, le foyer, le giron et le champ, exh. cat., Carré d’art, Nîmes (2004), Ed. Actes Sud/Carré d’art, Arles/Nimes, 2004

→Grenier Catherine (ed.), … oui j’ai dit oui je veux bien Oui , exh. cat., musée national d’Art moderne – Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris (1995), Editions de Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1995

Devenir Terrestre, Espace d’art Ducros, Grignan, Jully 2 – September 4, 2022

→La déesse d’en bas, L’assaut de la menuiserie, Saint-Etienne, May 20 – Jully 2, 2022

French sculptor and painter.

The seventh child of a farming family in the Drôme region, Françoise Vergier studied art in Avignon, later living in Le Havre and Paris before settling near Grignan, where she built a house-studio facing the beautiful Provençal landscape. Her country roots and attachment to the land, the garden, and the beauty of nature have left a long-lasting mark on her work. This singular artist is, in her words “in the in-between; between painting and sculpture, masculine and feminine, figures and landscapes, death and life.”

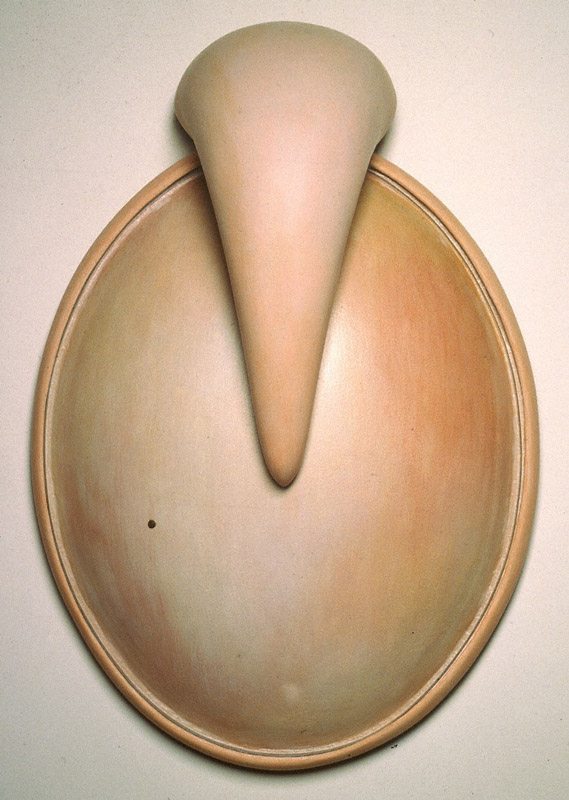

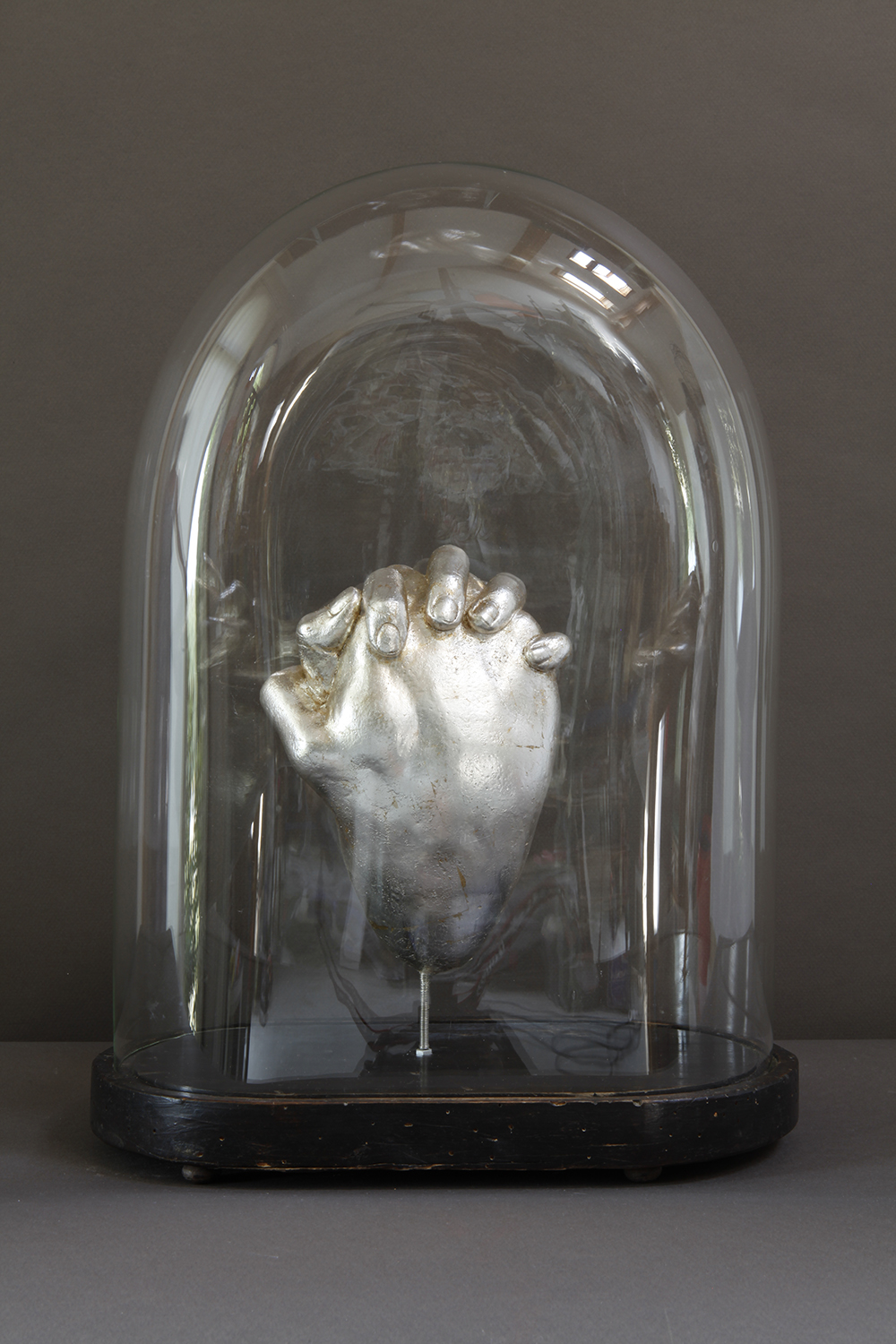

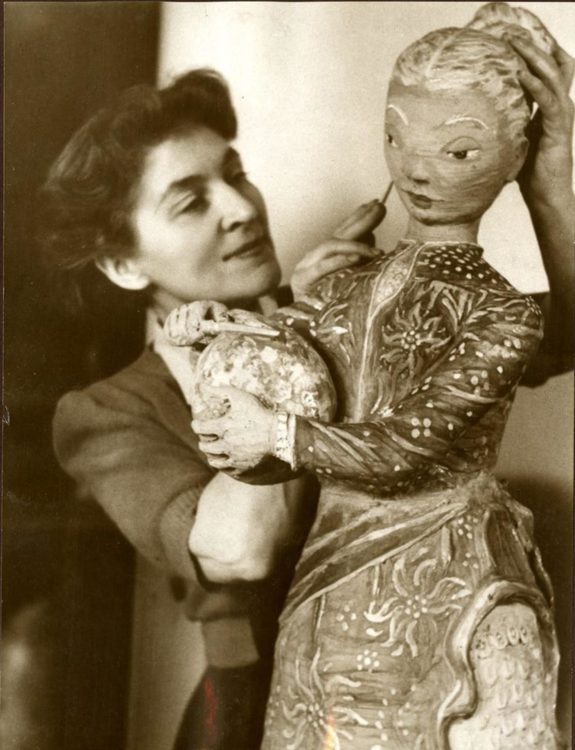

From her first sculptures of painted lime wood in the 1990s to her recent installations, marked by hybridity, mixing constructions of wood, ceramic objects, and fetishistic trinkets (Conversations avec une âme défunte, 2008), all of her work touches on the feminine, the erotic, on birth and disappearance. It is clear that Vergier believes in the therapeutic value of artistic creation and the magical power of art to soothe, fight against destructive forces, and help us reconcile with the world. Though often of autobiographical origins (allusions to motherhood, death of parents, the suffering of love), her sculpture-objects draw on universal archaic sources, and refer to ancient myths, such as those about the mother goddess.

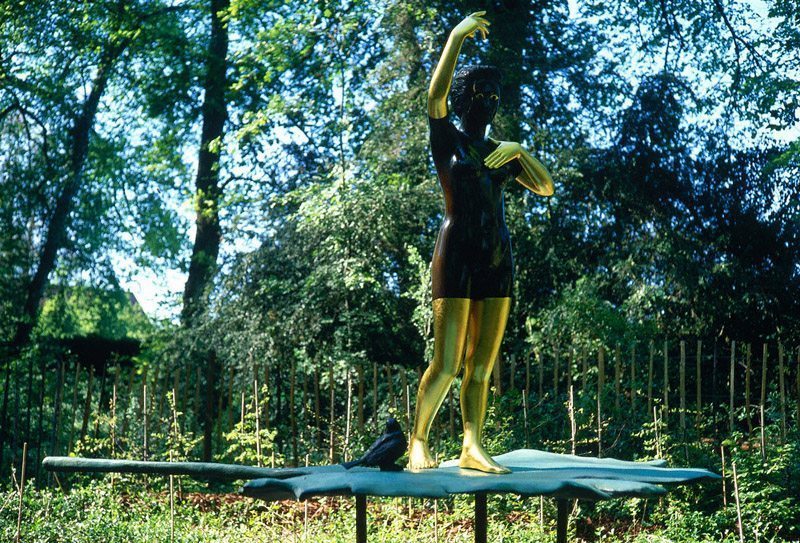

In an exhibition in 1995 at the Centre Pompidou, she presented a series of women carved in painted wood, with varying attributes and hieratic poses. She called them L’Insondable, L’Étrange, La Délicieuse, La Repoussante (“The Abysmal, The Strange, The Delicious, The Repulsive”), all qualifiers given to women by Arthur Rimbaud in his Lettre du voyant (“Seer Letter”). After previously having entrusted the realization of her sculptures to a craftsman, she decided to start making her feminine forms herself. And so glazed ceramic heads and torsos of women emerged, covered in painted landscapes, or various charms, evoking African fetishes.

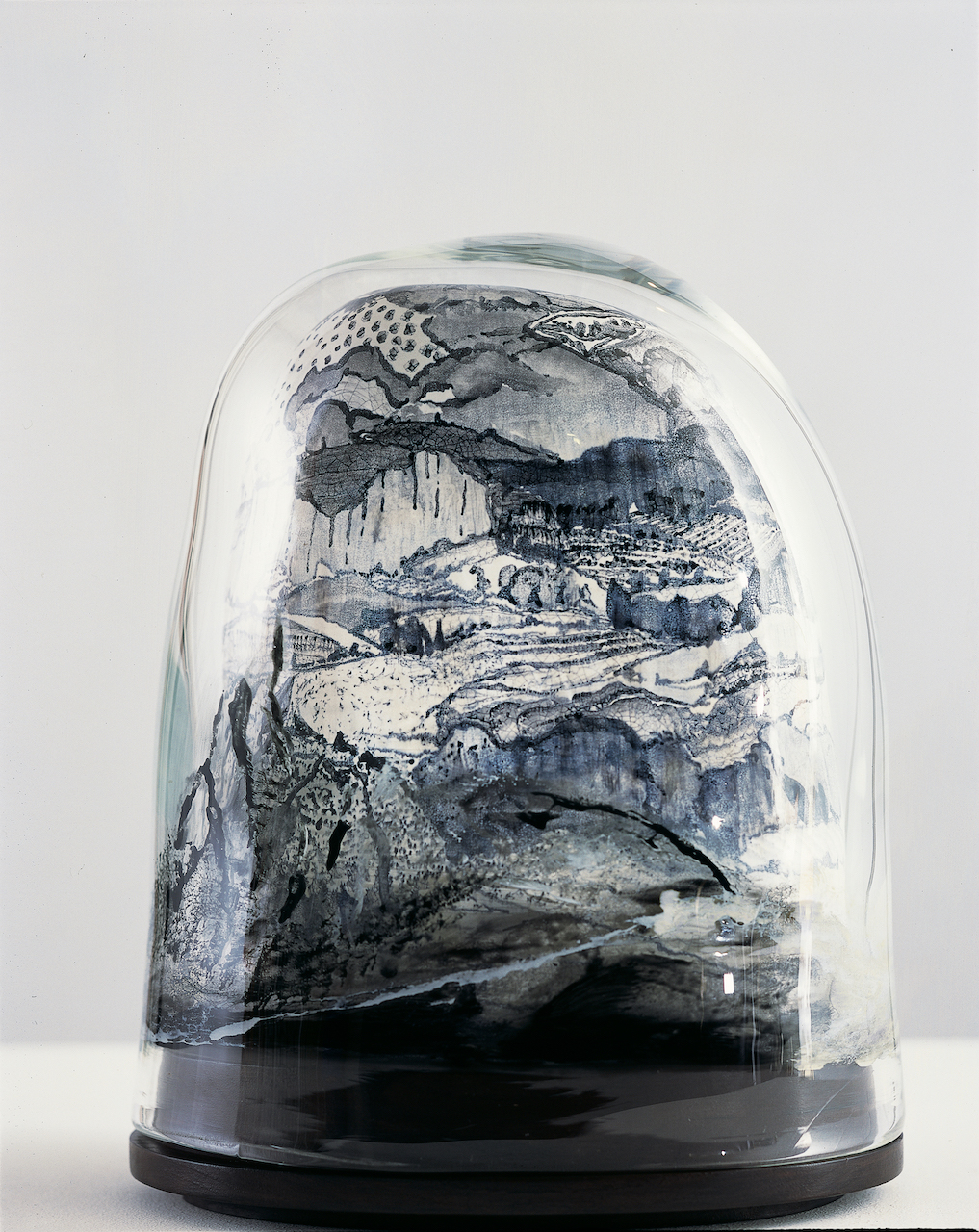

After ceramic, she turned to glass; at Cirva (International Research Centre on Glass and Sculptural Art, Marseille), Vergier produced numerous pieces of blown glass, a material that allowed her to give form to intangible elements, such as wind.

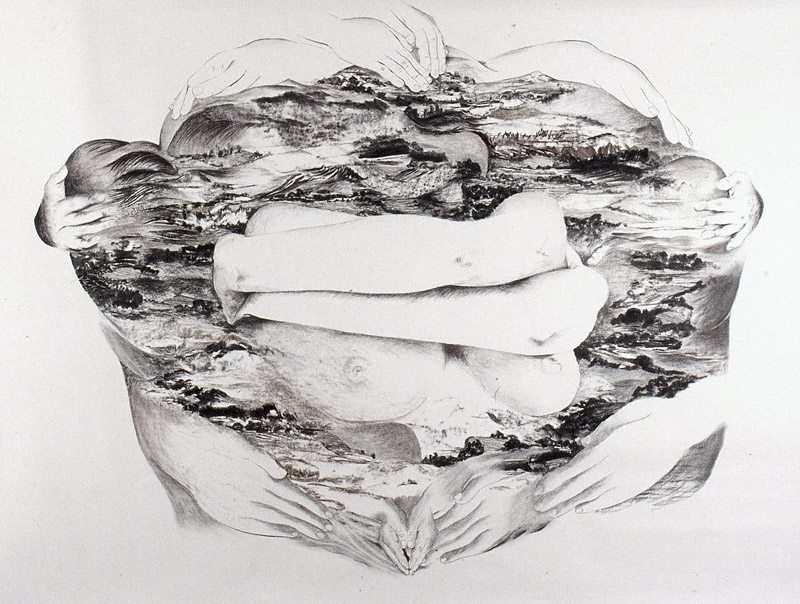

In addition to creating sculptural work, whose provocative side combining beauty, refinement, preciousness, and monstrosity recalls certain surrealist objects, she also draws large landscapes in charcoal, which layer hills and fields with body parts. These pieces, though landscapes born from her mind, nevertheless evoke the Chinese style of landscape painting. In 2004, a retrospective exhibition at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes (South of France), entitled Le Paysage, le Foyer, le Giron et le Champ, (“Landscape, Home, Bosom, Field”), gave her the opportunity to use her rich visual vocabulary, offering visual references to Michel Onfray, Peter Sloterdijk, and Diogenes. Avoiding any categorisation and mixing genres, her 2007-2008 sculptures are made up of assemblages of diverse objects and furniture that evoke funeral rites, such as her tribute to dead parents, which presents two small skulls sitting on a kind of leather-covered conch.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Francoise Vergier speaks about her work

Francoise Vergier speaks about her work