Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein, dite)

De la Haye Amy, Pel Martin, Gluck : Art and Identity, exh. cat., Brighton Museum, Brighton [November 18, 2017 – March 11, 2018], New Haven, Yale University Press, 2017

→Michalska Magda, “Gluck and Her No Prefix, No Suffix Queer Art”, Daily Art Magazine, February 21, 2018

→Souhami Siana, Gluck, 1895-1978: Her Biography, London, Phoenix, 2001

Gluck, The Fine Art Society, London, February 6 – 28, 2017

→Gluck : Art and Identity, Brighton Museum, Brighton, November 18, 2017 – March 11, 2018

British painter.

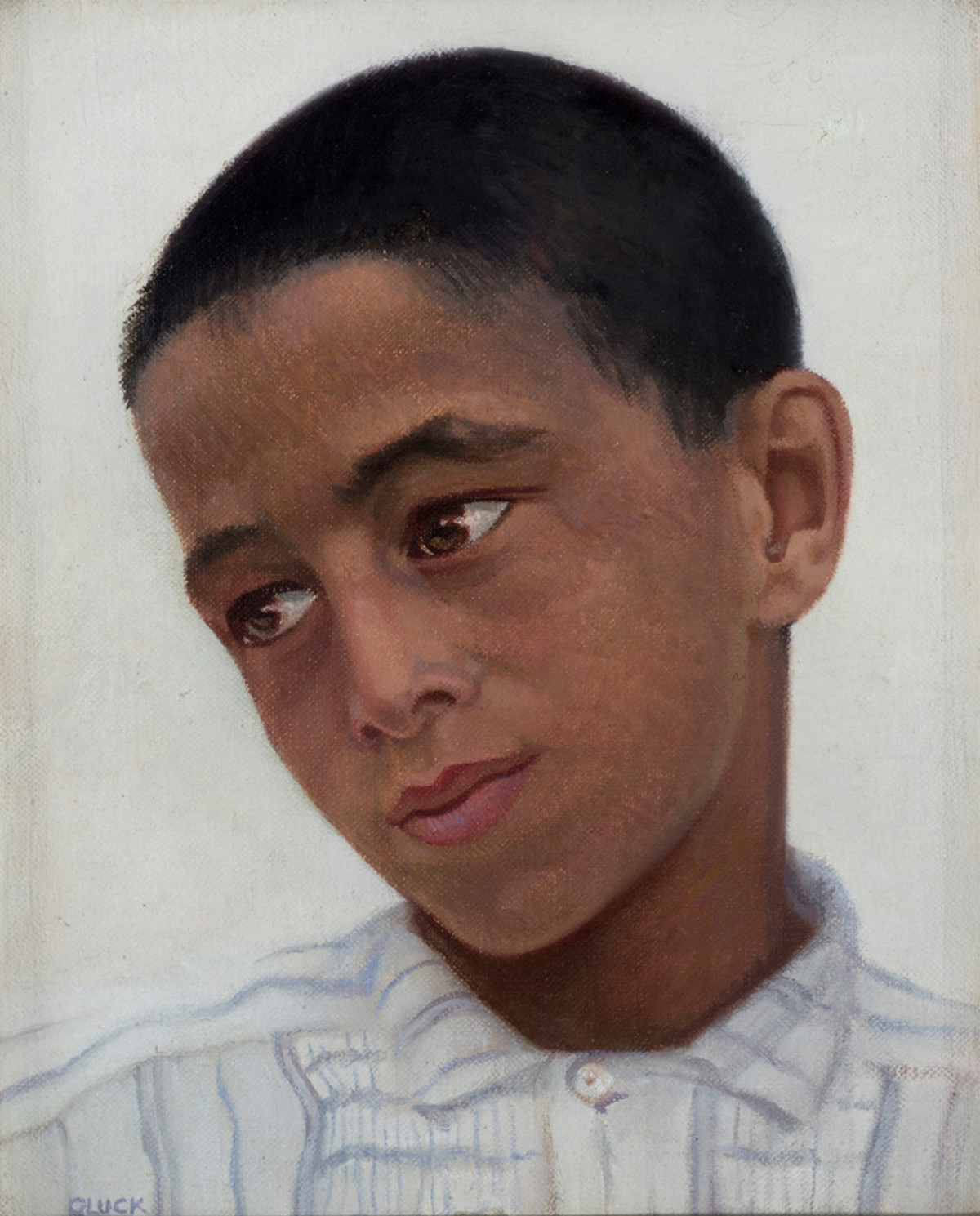

Born into a wealthy Jewish family – their father was the founder of the restaurant and hotel empire J. Lyons & Co. – the artist was to remain financially dependent throughout their lifetime, even though this was sometimes at odds with their spirit of rebellion. From 1913 to 1916 they studied at the St John’s Wood Art School in London, against the wishes of their parents, who did not approve of their artistic leanings. Together with their lover E. M. Craig, whom they had met at school, they then moved to Lamorna in Cornwall, where they both discovered the Newlyn School, an association of artists driven, much like the Barbizon School in France, by a fervour for painting outdoors, relishing the light and diversity offered by the landscapes. It was during this period that the artist defied social convention by acknowledging their gender fluid persona and dressing exclusively in so-called male clothes. They soon abandoned their birth name, Hannah Gluckstein, in favour of “Gluck”, with “no prefix, suffix or quotes”. Indeed, determined to make no concession, when the London Fine Art Society referred to them as “Miss Gluck” on an official document, they resigned.

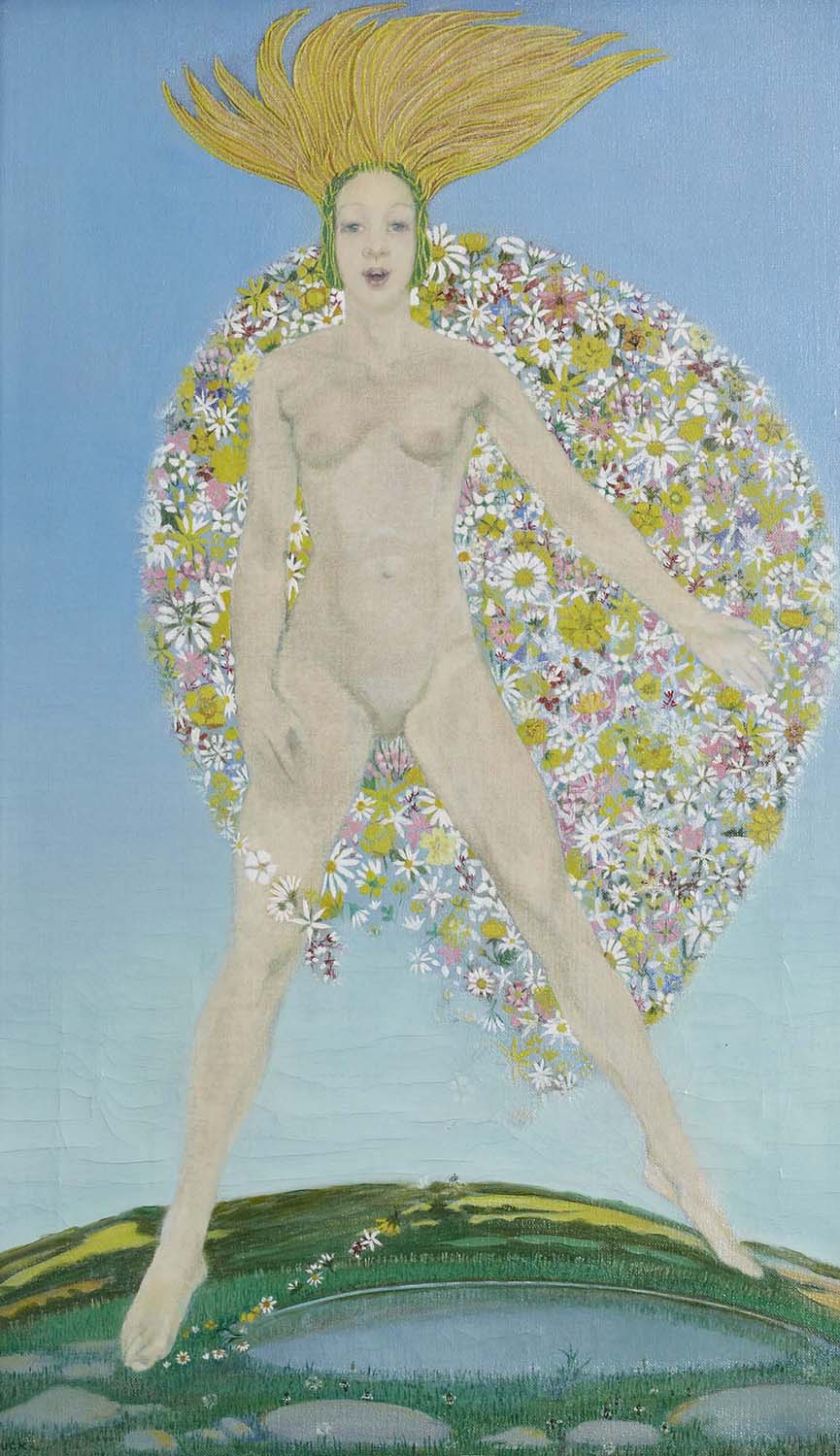

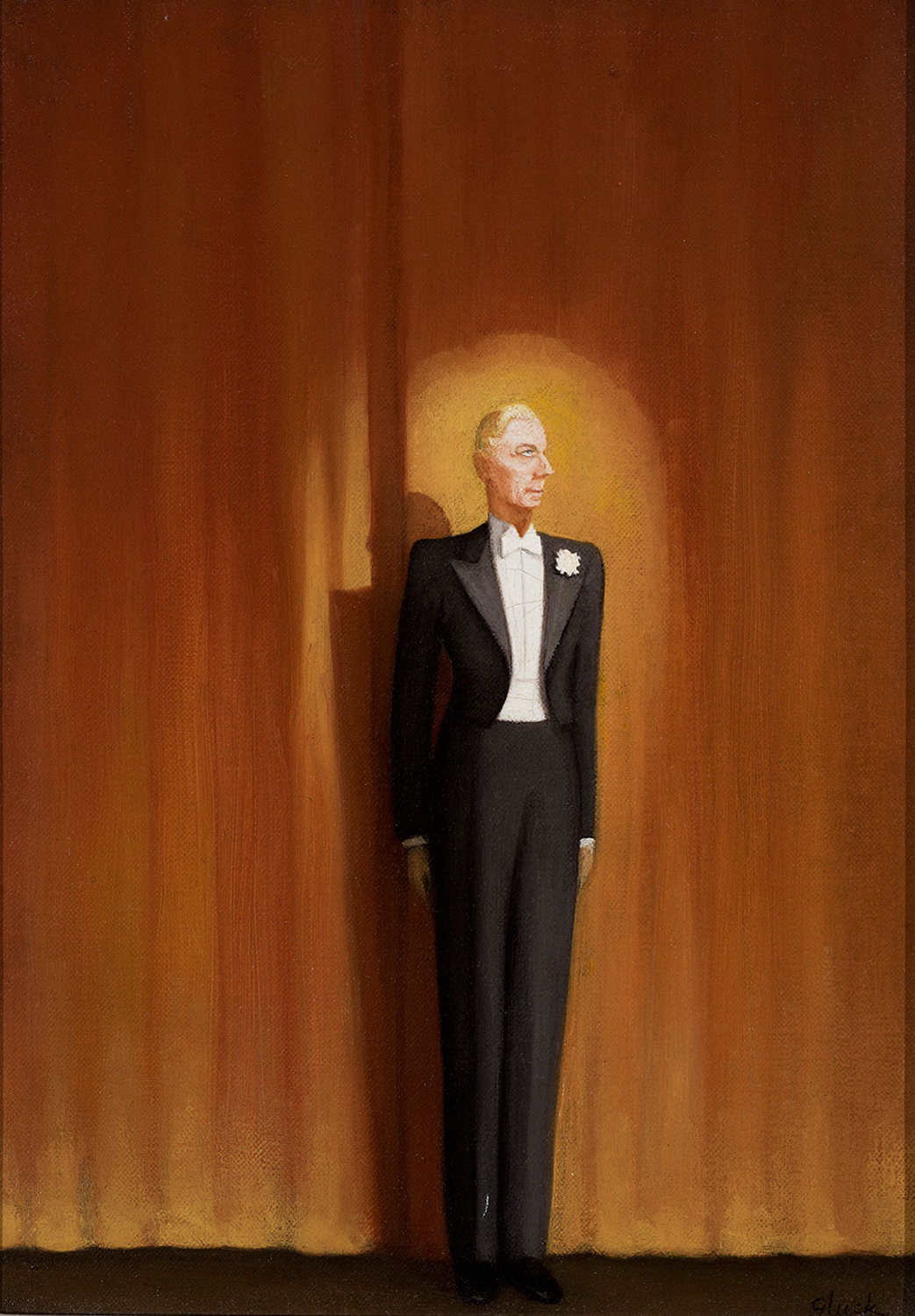

Throughout the 1920s their relationship with society journalist and writer Sybil Cookson led them to split their time between London and Cornwall. Their painting during this decade reflected both the peace and quiet of the English countryside and the effervescence of the capital’s cabarets, offering a glimpse of the lesbian and cosmopolitan night life of the Roaring Twenties. This duality also emerged through their first solo exhibition, Stage & Country, at the Fine Art Society in 1926.

In 1932 Gluck met florist and decorator Constance Spry, whose creations had a considerable influence on their work. Inspired by their partner’s bouquets, the artist painted still lifes and floral compositions with highly sexual overtones. They began to make a name for themselves – they had found their audience. C. Spry’s customers began collecting their canvases. It was also during this period that the artist developed and patented the “Gluck frame”: its three-tier conception was designed to meld into the architectural background of the work on display. In 1936 the artist left C. Spry and launched into a passionate affair with philanthropist and artist Nesta Obermer (1893–1984), who was married at the time. The following year saw the creation of Medallion (1936), which depicted the two lovers in profile. Their physical proximity mirrored the fusion of two beings. This canvas was soon to become an iconic emblem of lesbian visual culture and of Gluck’s whole oeuvre.

Profoundly affected by this relationship, the artist became deeply depressed when N. Obermer broke it off in 1944. They cut themself off from their entourage and destroyed a number of paintings. Almost 30 years ensued without any significant creations or exhibitions. They did however campaign relentlessly against manufacturers and the British Board of Trade to obtain the qualitative improvement of the painting materials available to artists, finally winning the day. In the 1970s Gluck experienced a new rush of creative fervour, and between 1970 and 1973 produced Credo: Rage, Rage against the Dying of the Light, a highly personal “epitaph” depicting a decaying fish head. The work was shown within the framework of a posthumous retrospective at the Fine Art Society in 1981.

In recent years Gluck’s oeuvre has been rediscovered and shown to the public, notably in the group exhibition Queer British Art 1861-1967 at Tate Modern in London (2017) and in the context of two monographic exhibitions, Gluck: Art and Identity at the Brighton Museum &Art Gallery (2017) and Gluck at the Fine Art Society (2017).