Gunta Stölzl

Regnier Isabelle, « La designer Gunta Stölzl, restée dans l’ombre du Bauhaus », Le Monde, August 14, 2019.

→Stadler Monika, Aloni Yael, Gunta Stölzl: Bauhaus Master, Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 2009

→Radewaldt Ingrid, Stadler Monika, Thöner Wolfgang, Gunta Stölzl : Meisterin am Bauhaus Dessau, Textilien, Textilentwürfe und freie Arbeiten 1915-1983 [Gunta Stölzl: Master at tthe Bauhaus Dessau, textiles, ttextiles designs and free work 1915-1983], Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 1997

Gunta Stölzl, Anni Albers, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, February 15 – July 10, 1990

→Droste Magdalena, Ellwangeer Marion, Gunta Stölzl, Weberei am Bauhaus und aus eigener Werkstatt [Weaving at Bauhaus and from our own worksjop], Bauhaus Archives, Berlin, February 4 – April 26, 1987 ; Kunstgewerbemuseum, Zürich, June 3 – July 26 1987 ; Gerhard-Marcks-Stiftung, Brême, August 16 – September 27 1987

German textile artist and designer.

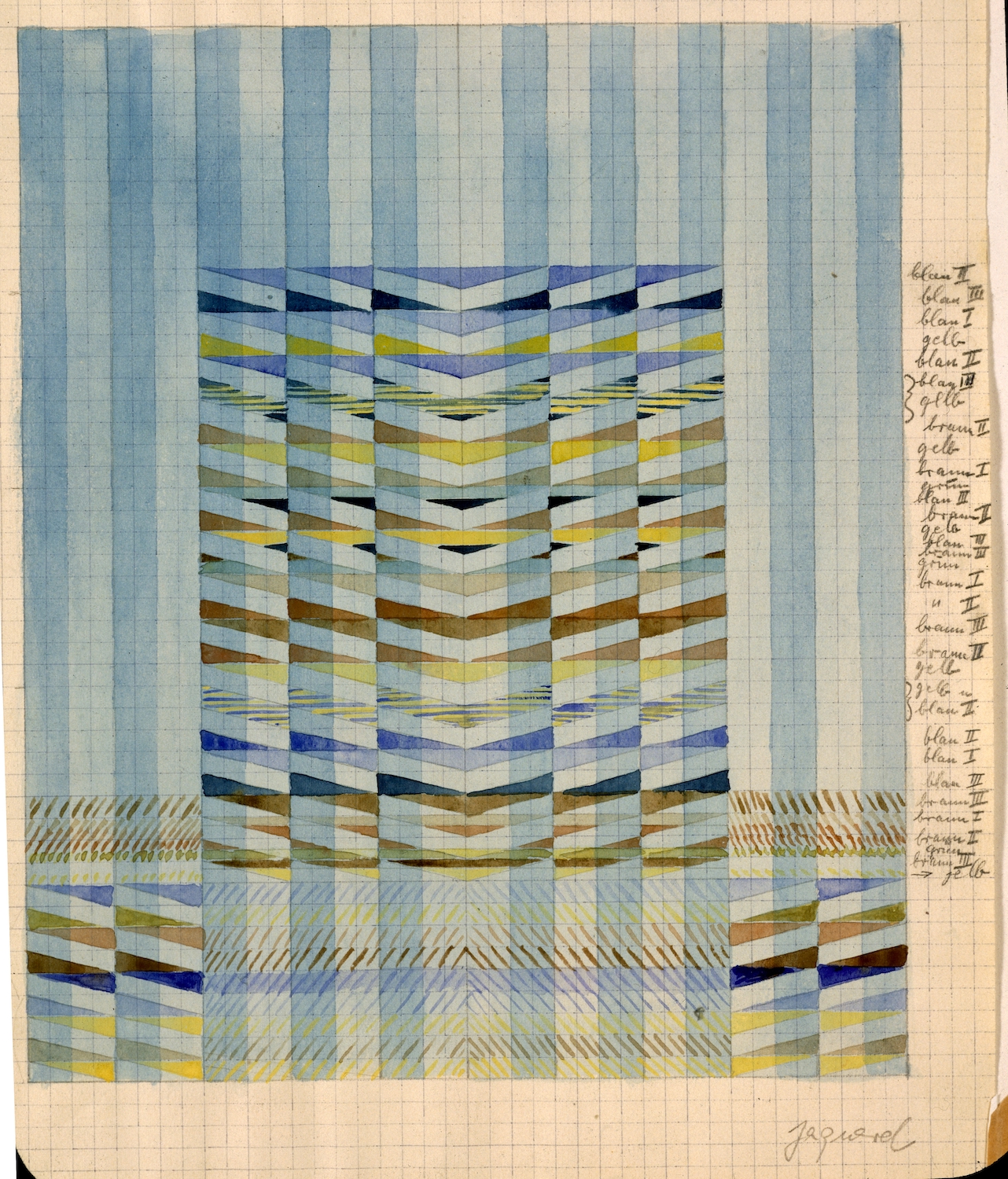

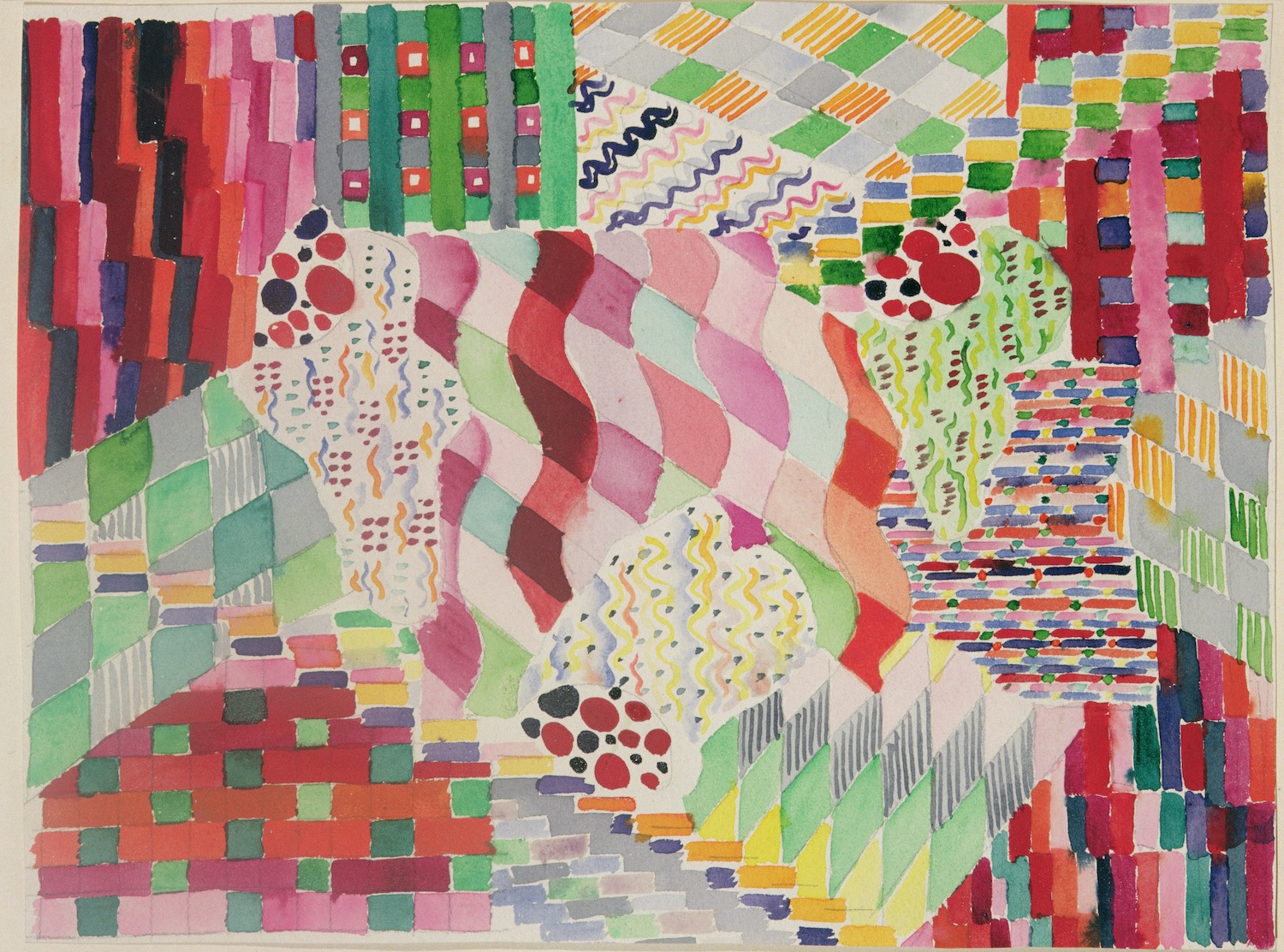

Gunta Stölzl was one of the most outstanding members of the Bauhaus. As the only woman to be officially named young master of a workshop – in her case, weaving – and as one of the few to have worked there for most of her life, she left an indelible mark on the history of the school. After studying at the Munich School of Applied Arts, she volunteered as a Red Cross nurse in 1917. This experience was to change her view of the world. After the First World War, she returned to the Munich art school, but then left it to join the newly opened Bauhaus in Weimar, in autumn 1919. Following the example of a number of art schools of the time, and per her personal convictions, in 1920 G. Stölzl offered to set up a women’s department. The Bauhaus director Walter Gropius agreed, but for his own reasons: he believed this tied in perfectly with his wish to restrict access of women to the workshops. The new women’s class merged with the weaving workshop, and G. Stölzl became its central figure. Here she could practice and transmit her mastery of the craft to others, adapting the theories of colour and harmony to the field of textile design. In the view of G. Stölzl, who became known for her often complex woven motifs, mastering the technical challenges had to go hand in hand with the search for a balance between form and material.

Thanks to the sustained support of her students at the weaving workshop, G. Stölzl was appointed head of workshop (Werkmeister) in 1927, and the following year she officially became the only woman director (Jungmeister) of a Bauhaus workshop. When the school moved to Dessau, G. Stölzl’s role became increasingly important as the real force behind textile innovation. She was in charge of the technical aspect of this innovation, focusing especially on adapting textiles to the new need to make them more resistant, less light-sensitive, and better adapted to modern usage.

Her masterpiece entitled Fünf Chöre (Five choirs) dates from that period. As revealed by textile-art historian T’ai Smith, this title was a

play on words, referencing music (Chor means both choir and chorus) and the jacquard weaving method, based on a system of cords. Musical harmony, perfect symmetry, and technical mastery are thus combined.

In 1931, G. Stölzl had to leave the Bauhaus because of an intrigue inside the weaving workshop. Over her twelve years at the school, she built up one of its most important workshops, and she is regarded as a major figure in the history of abstract textiles.

As published in Women in Abstraction © 2021 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London