Hanna Nagel

Hesse Herta, Hanna Nagel : Zeichnungen und Lithographien, cat. expo., Osthaus Museum, Hagen (1972), Hagen, Osthaus Museum, 1972

→Nagel Hanna, Ich zeichne weil es mein Leben ist, Karlsruhe, Verlag G. Braun, 1977

Hanna Nagel: Frühe Arbeiten 1926-1934, Kunstlerhaus, Karlsruhe, 1981

→Hanna Nagel, Frühe Werke, 1926-1933, Städtische Galerie, Karlsruhe, 2007

German draughtswoman and engraver.

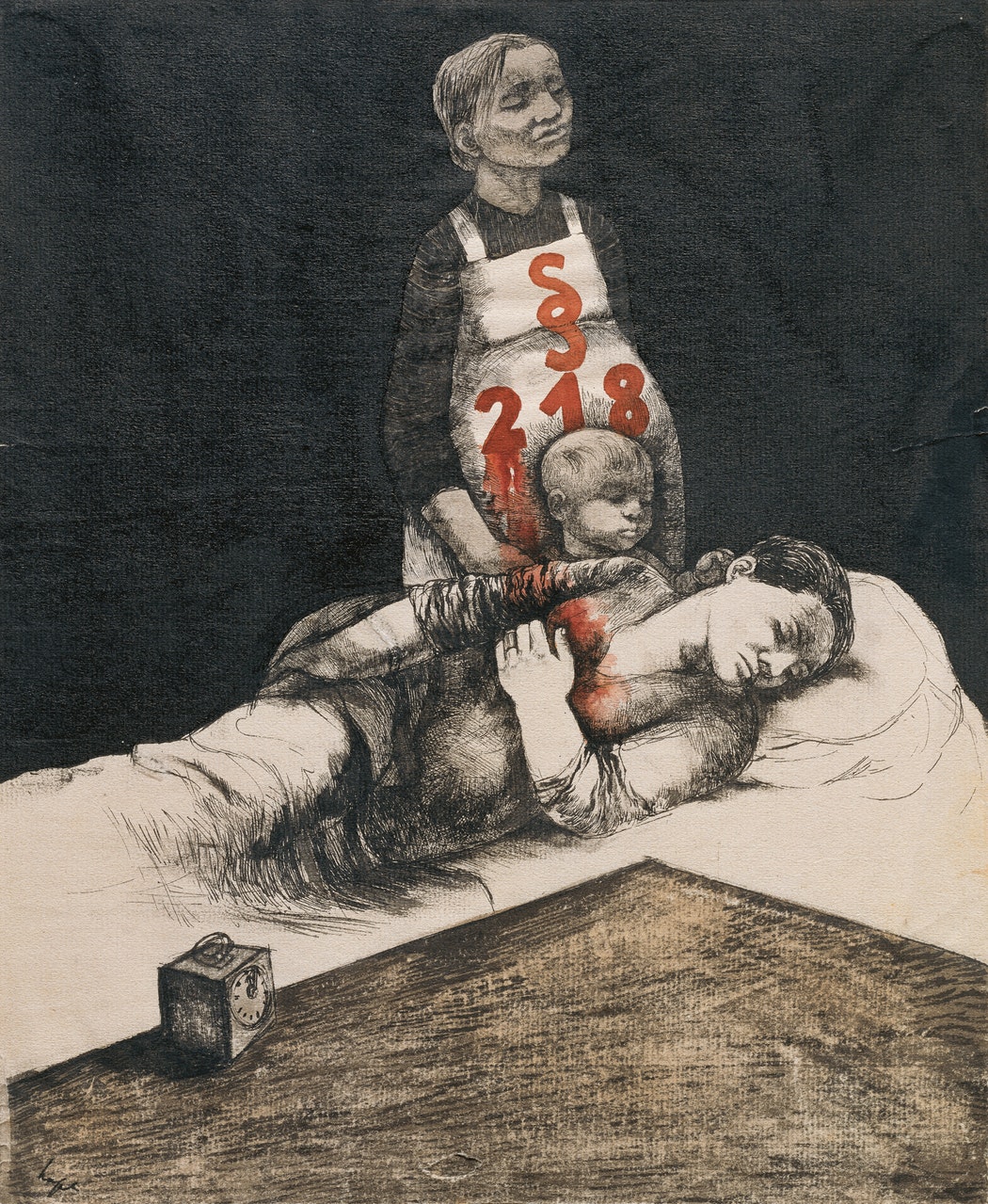

The daughter of a merchant and a teacher, Hanna Nagel was trained as a bookbinder before enrolling in the Fine Arts School in Karlsruhe in 1919. In an institution that had set up a lithographic and engraving studio at the beginning of the century, the young artist naturally turned towards these techniques, in which she demonstrated great skill. She took courses with Walter Conz, Wilelm Schnarrenberger and, most importantly, Karl Hubbuch, head of the Baden branch of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the post-war German movement that advocated for a realist representation of the contemporary world. This began the first period in the artist’s work: she followed the example of her professor in terms of themes, highly social content, as well as in her bold and sharp style, which was generally unflattering for models. However, contrary to K. Hubbuch, she chose to treat her figures alone, isolated in their environment, giving them a strange presence (Zigeunerin [gypsy], Munich, 1928; Mädchen mit Blauem Mantel [girl in blue coat], 1929). In 1929, she moved to Berlin, where she took courses with Hans Meid and Emil Orlik at the Fine Arts Academy. She married the painter Hans Fischer in 1931. This marked the end of her realist period.

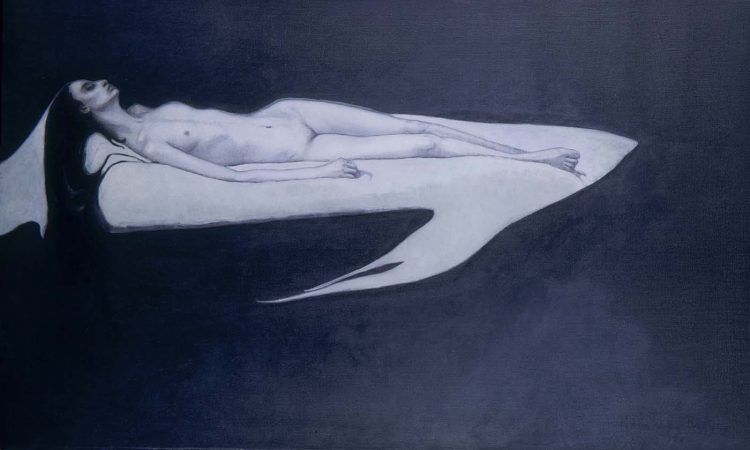

After the courses with E. Orlik, as well as her marriage, she preferred engravings to ink drawings and completely changed her approach. The representation of reality was succeeded by the mise-en-scène of the interior world. In 1933, she was awarded the Prix de Rome just before Hans Fischer, and the two artists moved to the Italian capital for two years together. After returning to Germany, she began working as an illustrator, particularly for Russian authors, until her death. In 1937, she received a silver medal in the graphic section of the International Exhibition of Paris. One of her masterpieces from this period is the free interpretation she gave to Chopin’s preludes in a series of drawings from 1945. In 1998, the city of Karlsruhe initiated the annual Hanna Nagel Prize for artists over forty.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019