Hanne Darboven

Hillings Valeri, Hanne Darboven: hommage à Picasso, exh. cat., Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin (4 February–23 April 2006), Berlin/Ostfildern, Deutsche Guggenheim/Hatje Cantz, 2006

→Berger Verena (dir.), Hanne Darboven: Boundless, Ostfildern, Hatje Cantz, 2015

→Adler Dan, Hanne Darboven: “Cultural history, 1880-1983”, London/Cambridge, Afterall Books, 2009

Hanne Darboven: Wende ›80‹, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, 1983

→Hanne Darboven, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, 1999-2000

→The order of time and things: The home studio of Hanne Darboven, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 26 March–1 September 2014

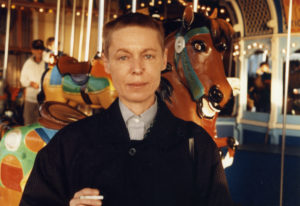

German conceptual artist.

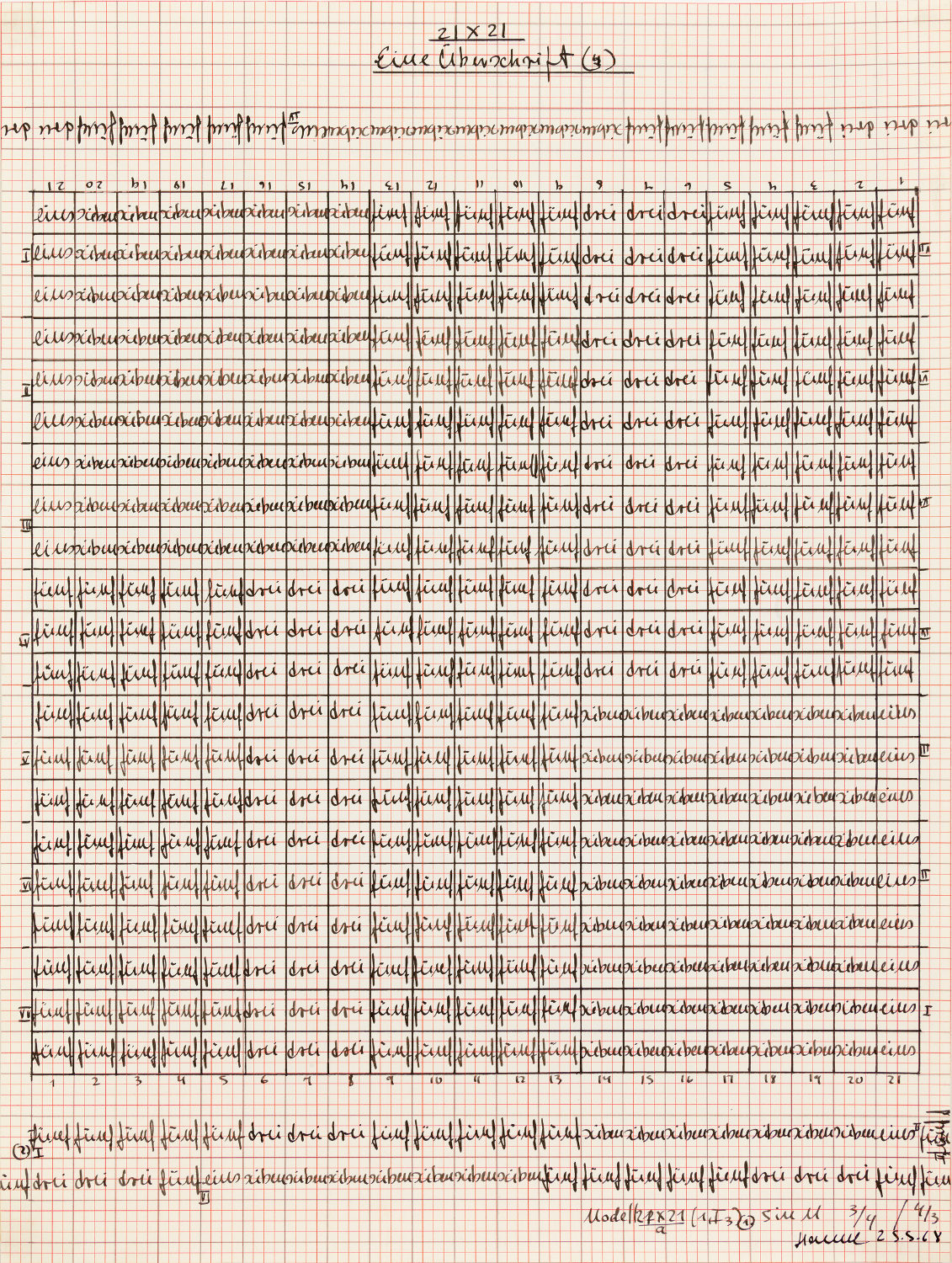

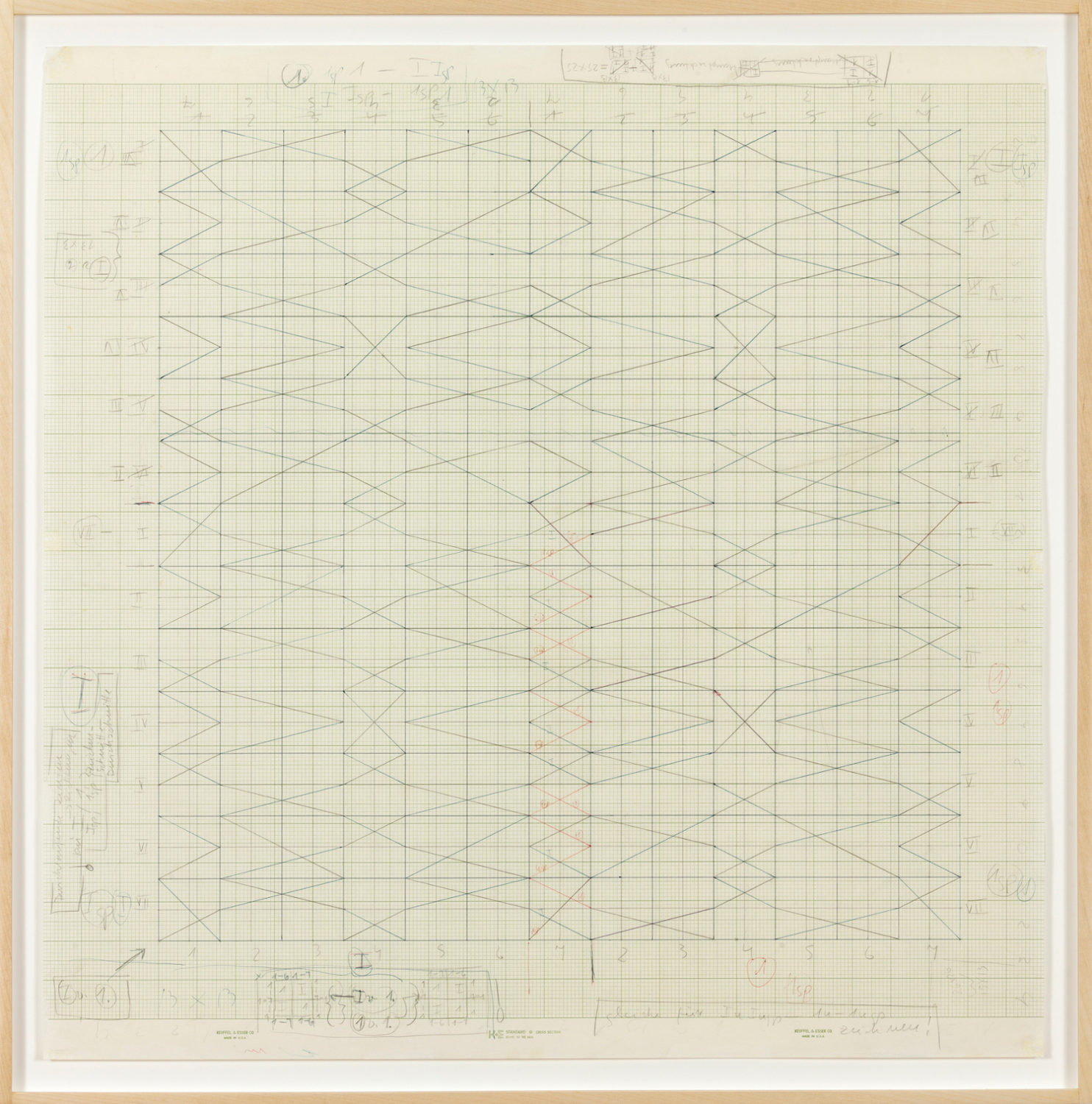

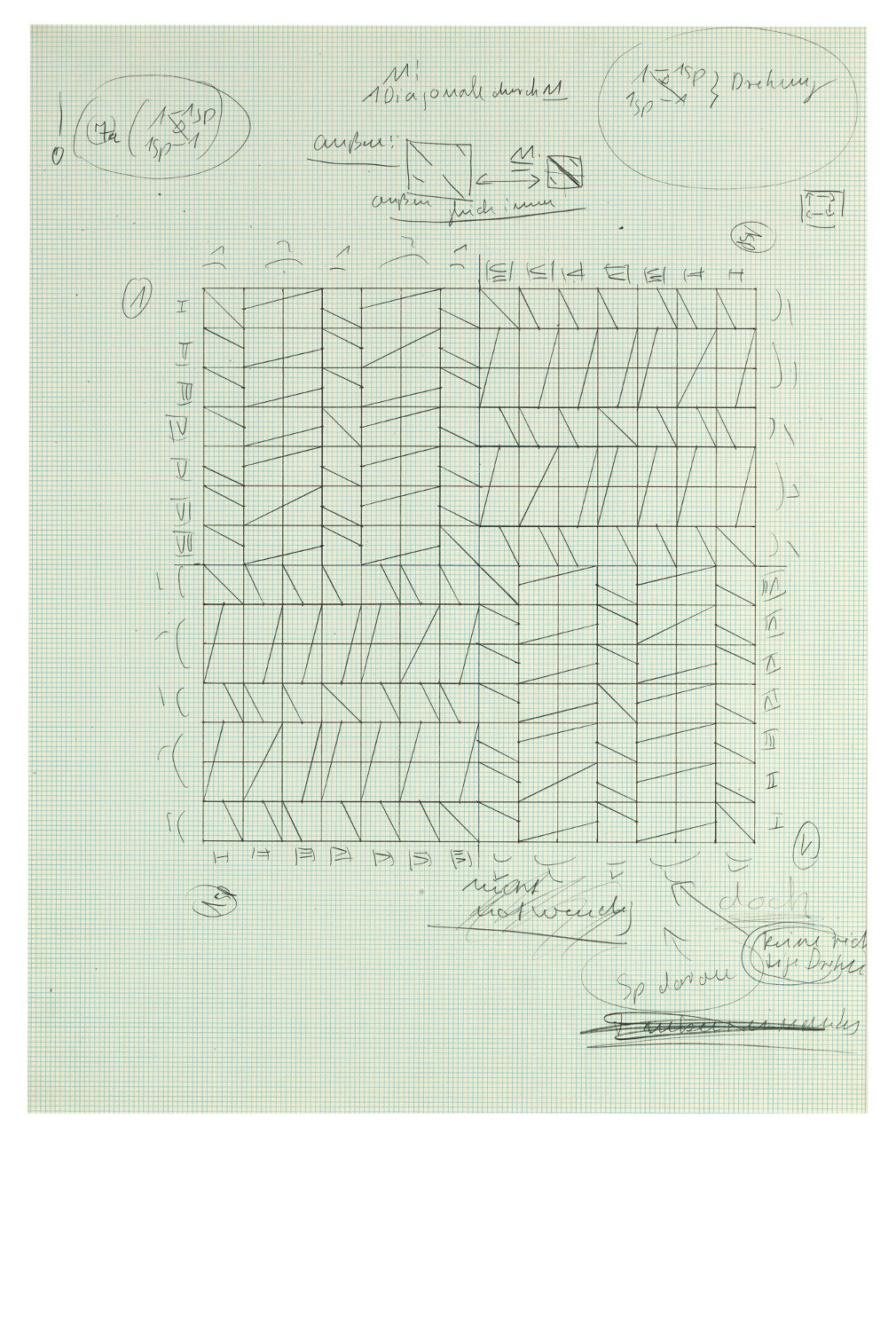

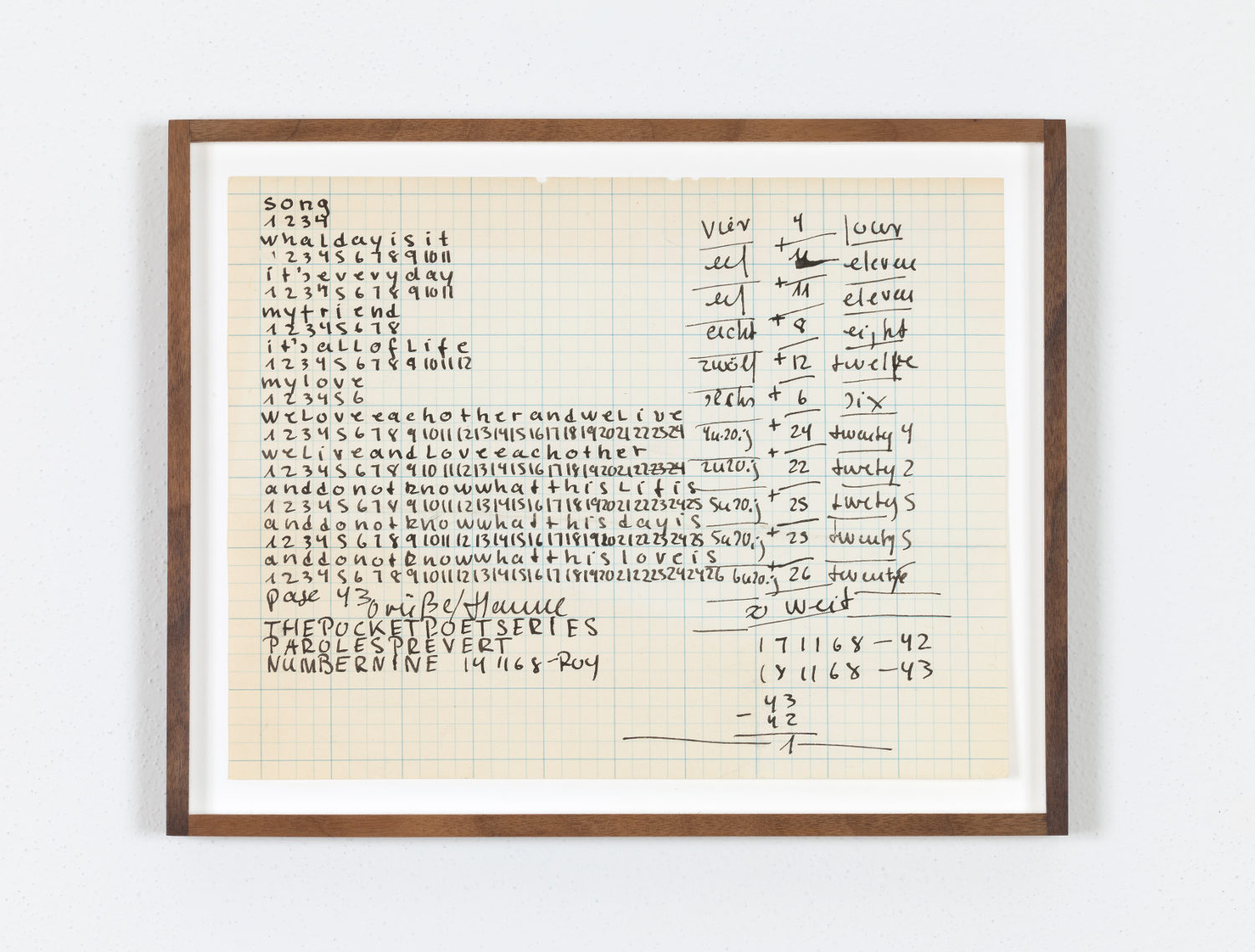

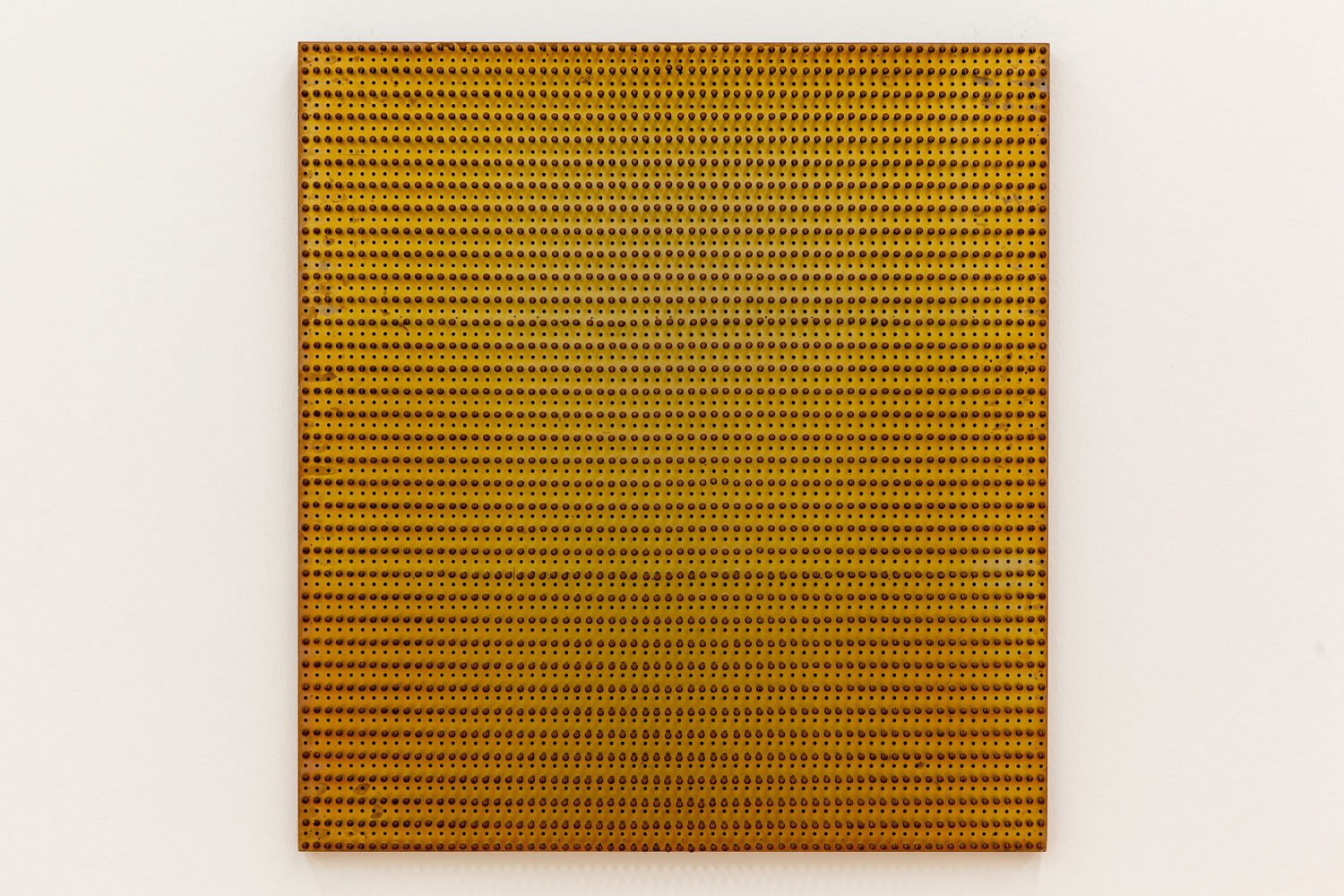

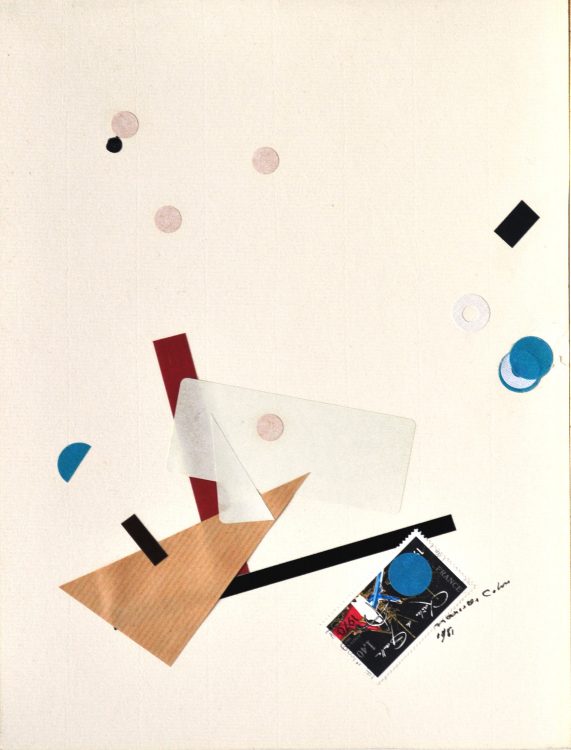

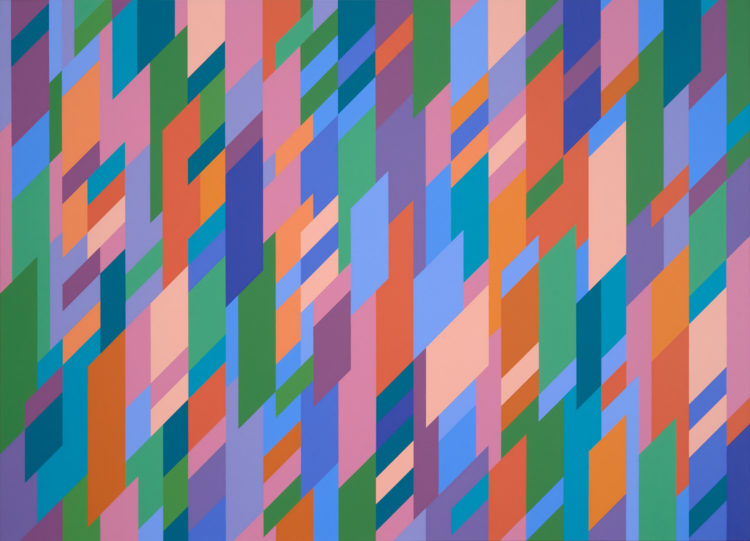

Born into a family of retailers from the high bourgeoisie of Hamburg, Hanne Darboven grew up in a very open atmosphere with a strong interest in the arts, particularly music. An excellent pianist since childhood, she gave up her musical activity in 1962 to study painting at the fine arts school in Hamburg. Between 1965 and 1968, she lived in New York, where her research led to her creation of increasingly minimalist works and she did away with most of the artworks she had brought with her from Germany, leaving them in the street. The construction of her abstract drawings soon came to rely on geometric or algebraic operations (addition, permutation, inversion). She thus played an important role in the development of conceptual art in the United States: this movement supports the idea that the essence of an artwork is its intellectual content and that the clear formulation of the project of a creation suffices for it to exist in the fullest sense; this affirmation is closely linked to a rejection of the production of objects (paintings, sculptures). In the career of the young artist, the rejection of painting thus assumed the form of a radical breakaway. In August 1968, after the death of her father, she began work on dates, which she transformed through the calculation of the horizontal sum, in unique digits known as “K-Wert” [K-values], with the aid of her Konstruktion (a system for extracting a digit from any given date). Subsequently, she entirely abandoned the correlation between numbers and drawing, and theorising the passage of time was to become an essential element of her œuvre. In 1980, she revived the musical practice of her childhood and started to correlate digits and notes. In this way, she devised compositions that were played by orchestras and published in the form of scores and CD-ROMs. Since her project of copying out Homer’s Odyssey by hand, which she abandoned in the early 1970s, rewriting played a major role in her work. From 1975 to 1982, she undertook Schreibzeit (“writing time”): 3 000 pages arranged into seven folders, the majority of which comprised passages from widely varying texts that she transcribed by hand. She included excerpts from contemporary newspapers and magazines (notably the weekly paper Der Spiegel), but also aphorisms by Georg Christoph Lichtenberg. Beyond the choices that she established, her personal interventions in theses texts were very rare. Through this assemblage, she aimed to show the imbrication of art and politics, from Bismarck through to the consequences of fascism within the young Federal Republic of Germany. But it was not a question of merely writing out texts word for word. She often replaced “units of meaning” by undulating lines. The temporality of the gesture of writing thus predominated over the constitution of any meaning that would be expressed by the words.

Her writing projects are often explicit tributes to philosophers (Evolution Leibniz, 1986), to inventors, to statesmen (Bismarckzeit [Bismarck], 1978), or, more rarely, to artists (Homage to Picasso, 1995-2006; Quartett’88, 1988-1989, dedicated to four women: Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Marie Curie, and Rosa Luxemburg); finally, sometimes even to ideas (human rights, the city of New York, the ideas of the Enlightenment). Towards 1979, images from diverse sources (photographs, reproductions, newspaper covers) were added to these ensembles. In 1999, she exhibited a choice of artworks produced in her childhood and during her studies in Hamburg (Hanne Darboven, Das Frühwerk [Hanne Darboven: Early Works], 1999-2000), in a latter-day rehabilitation of her past as a budding artist. The interest in her own past was here clearly aligned with her interest in the writing of history. It was the importance that she gave to an essential date in her personal life (that of the death of her father) that brought the notion of temporality into her artwork, marked by the relationship between world history and personal history. The tension between personal time and the overall passage of time related to the existing tension between the choice of highly emotionally charged subjects and their almost mechanical treatment. Therefore, despite the sensation of cold impassivity that her works often evoke, they nonetheless almost always contain an intense sentimental dimension that the spectator can discover by tracing back to the origins of the artwork. The rigour with which the work is executed thus emerges as the result of an exercise in self-restraint or a personal spiritual quest that appears to be rooted in a life traversed by the same accidents, joys, and sufferings as our own.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

The Art of Hanne Darboven

The Art of Hanne Darboven  Nick Mauss and Ken Okiishi on Hanne Darboven

Nick Mauss and Ken Okiishi on Hanne Darboven