Helene Schjerfbeck

Holger Lena, Helene Schjerfbeck, Helsinki, Ateneum, Finnish National Gallery, 2016

→Ahtola-Moorhouse Leena (ed.), Helene Schjerfbeck: Finland’s Modernist Rediscovered, exh. cat., Finnish National Gallery Ateneum, Helsinki / Philips Collection, Washington (1992), Helsinki, The Finnish National Gallery Ateneum, 1992

→Facos Michelle, “Helene Schjerfbeck’s Self-Portraits: Revelation and Dissimulation”, Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 16, no. 1, 1995

Helene Schjerfbeck, Stenman Gallery, Helsinki, 1917

→Helene Schjerfbeck: Finland’s Modernist Rediscovered, Finnish National Gallery Ateneum, Helsinki, Philips Collection, Washington, 1992

→Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946), Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, 20 October 2007–13 January 2008

Finnish painter.

Coming from an originally Swedish family, the young Helene Schjerfbeck became keenly involved in the visual arts. Adolf von Becker, an influential member of the Finnish Society of Fine Arts, authorized the young girl to enroll in his drawing school in 1873. As that 19th century drew to an end, Finland was already putting artists of both sexes on an equal footing. Flush with a government grant, the young woman embarked on her artistic career in Paris, where she was trained at the Parisian Colarossi academy (1881-1884), before staying in Concarneau and Pont-Aven, a fashionable artistic colony even before the arrival of Paul Gauguin, Charles Laval and Emile Bernard in 1886.

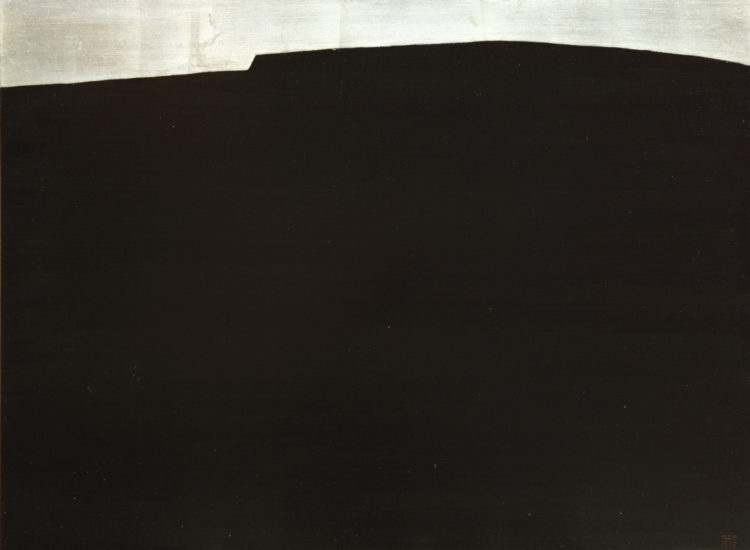

Her sketches from those days were done in an international realist style. In tandem with her picturesque but still conventional peasant scenes, she experimented, from that period on, with a more daring kind of painting: so La Porte (1884) is striking for its spare quality, its absence of any perspectival references, and its monochromy. At the same time the artist discovered the open air painting—pleinairisme—of the Barbizon school: evidence of this lies in the forest landscapes energetically brushed in the early 1880s (L’Allée, 1882-1884). She swiftly separated herself from formal apprenticeship and standard subjects, while still continuing to practice a consensual style for the works which she presented in competitions: La Convalescente (1888) won a bronze medal at the 1889 World Fair, at a time when Gauguin, Bernard, Laval and Louis Anquetin were unveiling synthetism. It is not known if, while then in Paris, she visited the Volpini Exhibition—the first show of the Impressionist and Synthetist group. The fact remains however that, in the wake of the World Fair, her style became increasingly coherent. Her wavering between naturalism and open air painting tended to disappear in favour of a linear painting, where areas of pure colour replaced decorative arabesques. But her paintings, in particular the silent and monumental portraits, call to mind not so much the Nabis, as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (Ma mère, 1902) and Edouard Manet (Jeunes filles lisant, 1907). After 1910, having returned once and for all to Finland, she tirelessly took up the same motifs, producing several versions of the same picture a decade or two apart. Her output was confined to three or four genres (portraits, still lifes, landscapes, and re-interpretations of old pictures, including El Greco’s), abandoning the great symbolic and narrative subjects, typical of the nationalist Finnish painting of an artist like Akseli Gallen-Kallela. She also focused on studying her entourage.

Like Henri Matisse, whom she admired, she proposed the turn-by-turn colorist, graphic, decorative and matierist transposition of a given theme, alternating media and techniques. There was never any question of studies for a final picture, but of variations on one and the same theme. She was independent, but remained in touch with the pictorial revolutions that were stirring Europe. On several occasions she flirted with the Fauvism of an artist like Kees Van Dongen, the Expressionism of someone like Egon Schiele, and even abstraction; the series of Compositions of 1915 and the Fenêtres d’église of 1919 betray a powerful tension between an attachment to reality and a temptation to dissolve the subject. Her love of the daily round clashed with the ongoing desire to experiment with and revive methods of representation, and distortion. This expressionist development found its full voice with her self-portraits of old age. Even more so than the aged Pierre Bonnard, and more violently than Edvard Munch in the 1940s, she emphasized the deterioration of the body by inflicting a deformation on her face, a destructive simplification which was abrasive, like an acid. Geometrized, blurred, scratched, twisted, and crossed out, the faces’ features are reduced to the sombre ghostly effigy of Une vieille artiste peintre (1945), the painter’s final encounter with herself. Working in solitude, she pursued an itinerary that was first dazzling and then silent and introspective, that of a “painter monk” turned just as much toward the relentless study of the human figure as toward a quest for novel formal solutions.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Helene Schjerfbeck’s exhibition at musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris

Helene Schjerfbeck’s exhibition at musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris