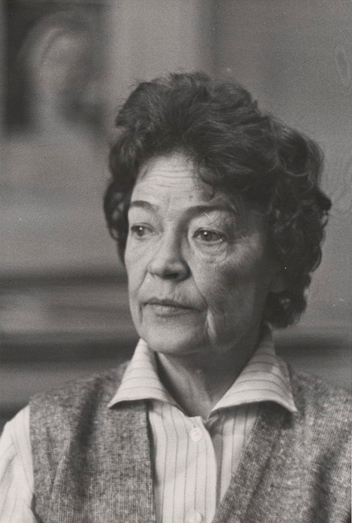

Inji Efflatoun

Didier Monciaud, « Les engagements d’Injî Aflâtûn dans l’Égypte des années quarante : la radicalisation d’une jeune éduquée au croisement des questions nationale, femme et sociale », Cahiers d’histoire, n°126, Paris, 2015

→Anneka Lenssen, « Inji Efflatoun: White Light », Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, « Public/Private: The Many Lives of ‘Rebel Painter’ Inji Efflatoun », Afterall, n°42, London, autumn-winter 2016

→Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, Nada Shabout, What We Want to Say: Arab Art in the Twentieth Century – Primary Documents, New-York, Museum of Modern Art, 2017

Enji Efflatoun, tourning exhibition, Moscou, Prague, Sofia, 1974

→Barjeel Art Foundation Collection – Imperfect Chronology: Debating Modernism I, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 8 September – 16 December 2015

→Mother Tongue: Selected Works by Inji Efflatoun, Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha, 2015-2016

Egyptian painter.

Inji Efflatoun was born in 1924 to a wealthy family from Cairo’s French-speaking aristocracy. Her mother, a divorcee, opened the first tailoring shop run by a woman. Inji Efflatoun received a strict catholic education before studying at the French Lycée in Cairo, where she became familiar with Marxism. She started painting very early on and, from the age of fifteen, took classes with Kamel el-Telmissany, one of the representatives of Egyptian surrealism. The painter introduced her to the “Art et Liberté” (“Art and Freedom”) movement, a group of artists and intellectuals of communist and anti-imperialist orientation which made use of surrealist creative processes – an influence perceptible in the artist’s earlier output.

Inji Efflatoun quickly asserted her political stance in “Art et Liberté” by engaging in intense militant activity for the better part of fifteen years as from 1940. She was one of the first women to study in the arts department of the University of Cairo, and in 1945 she took part in the creation of the Ligue des jeunes femmes des universities et des instituts (League of young women in universities and institutes), which promoted left-wing, anti-colonialist politics, and campaigned for gender equality. Working for a short while as a teacher and as a journalist, she published several manifestos and, with a small group of women intellectuals and militants, participated in numerous actions in Egypt and Europe in favour of women’s rights and peace.

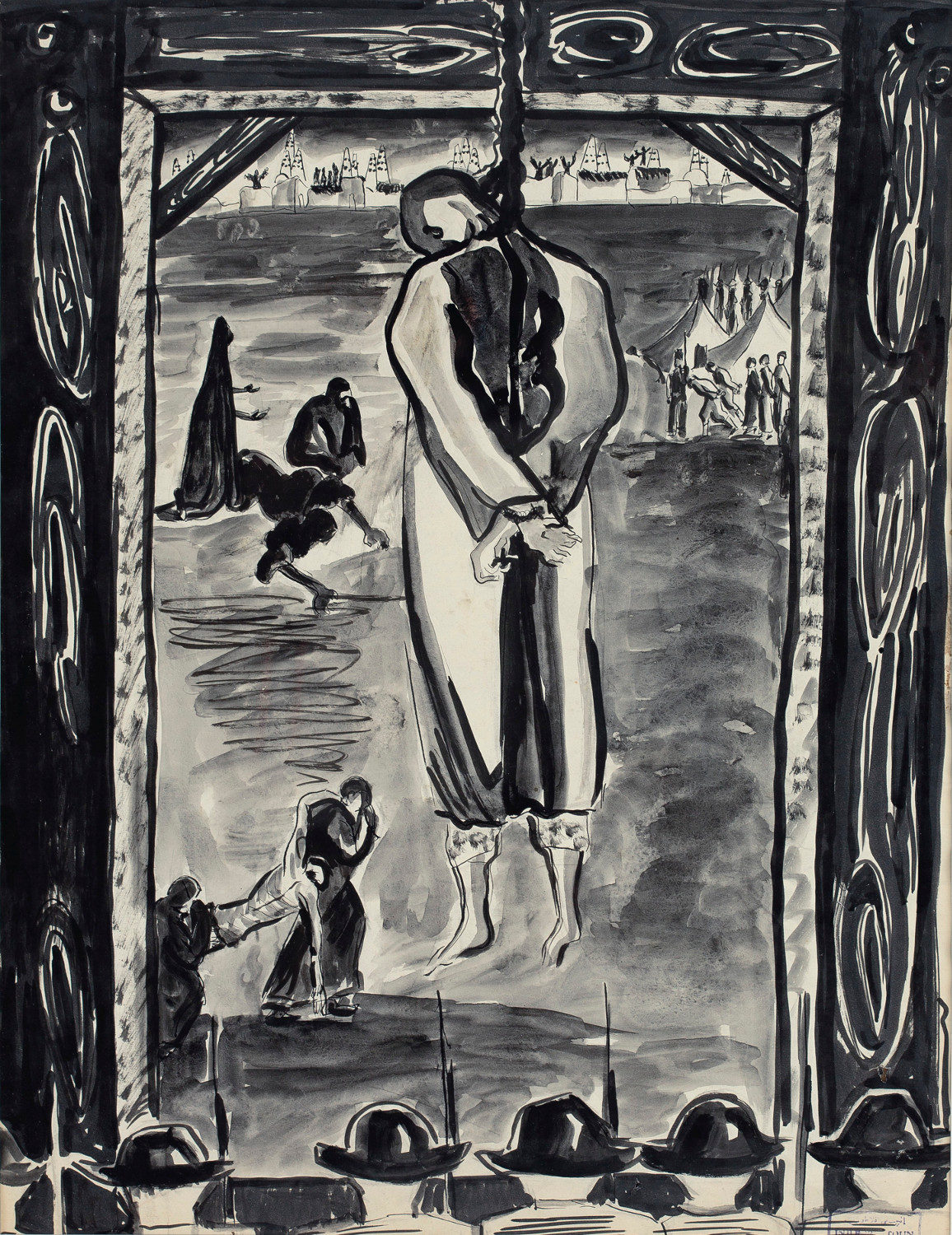

The 1950s saw Inji Efflatoun’s renown grow in Egyptian and international artistic circles. Her work was presented at the new Egyptian Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale and at the 2nd São Paulo Biennale in 1953. In the latter half of the 50s, probably influenced by her meeting with the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, her style moved further towards socialist realism. She painted portraits of the fellahin, Egyptian landless peasants, revisiting several violent episodes of the British occupation, particularly in her ink on paper The Dinshaway Massacre. The political activism she continued to engage in clandestinely led to her arrest in 1959 by Nasser’s forces during a wave of apprehensions targeting communists. She was imprisoned for over four years in an undisclosed camp.

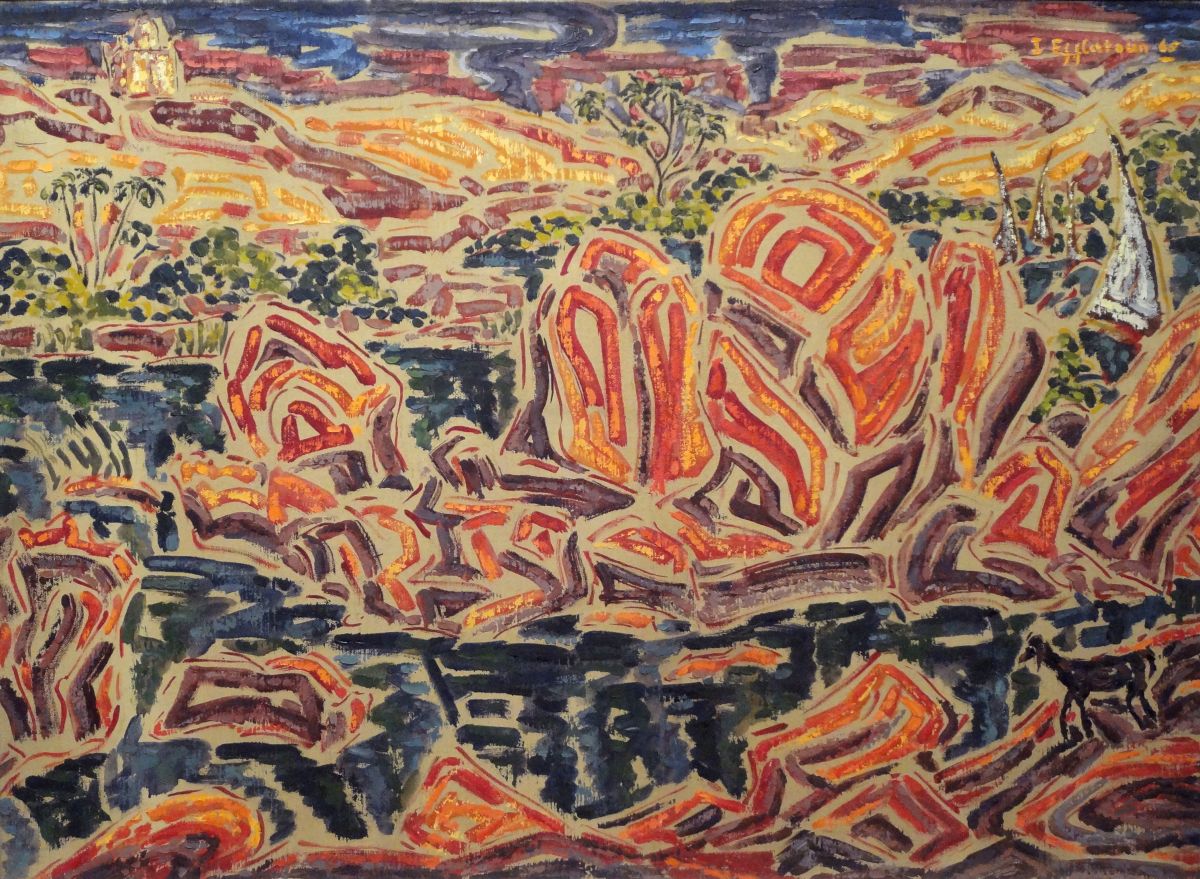

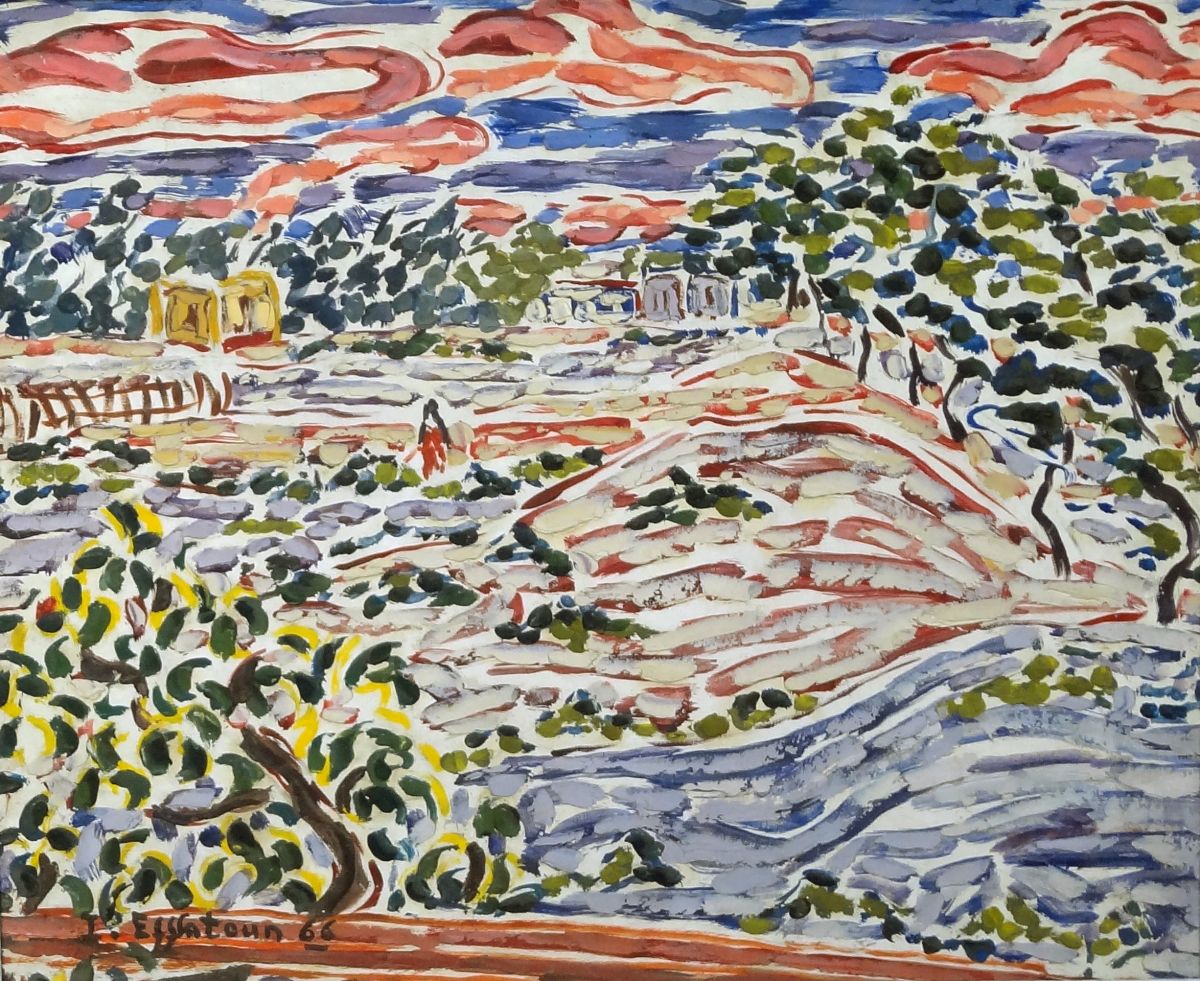

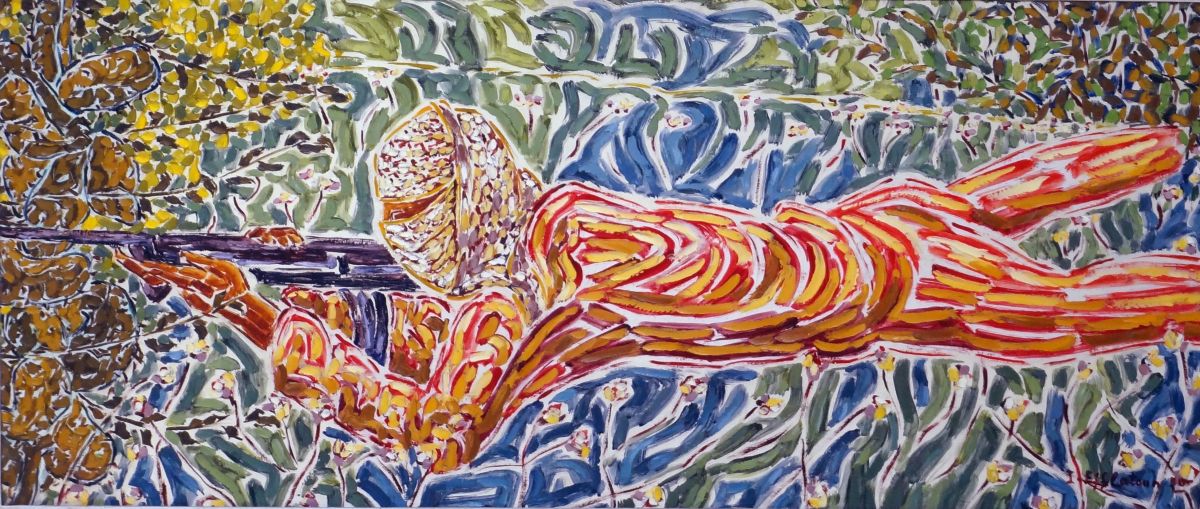

From her liberation in 1963 to her death in 1989, Inji Efflatoun devoted herself to painting and took part sporadically in the political life of her country. Her work was shown in Egypt and Europe, and she became a respected figure in the art world. Her interest in the working class continues to manifest itself in her many depictions of landscapes and scenes of rural life. However, her style has become more contemplative, with greater importance given to reserve, which she calls “white light”.

Inji Efflatoun’s pictorial work and militant legacy, documented in her writings and memoirs, are part of the modern history of Egypt and have widely circulated in the Arab world. Part of her work is shown at the Museum of Modern Art in Cairo. Although very little known in Europe, it has met with growing interest in the past few years and has been the subject of several exhibitions, as well as being studied and written about in universities in Europe and the United States.

© 2017 Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Inji Efflatoun After Prison

Inji Efflatoun After Prison