Focus

Pushpamala N., The arrival of Vasco de Gama, 2014, Giclee print on canvas, concept, production and direction: Pushpamala N., © Photo: Clay Kelton, 152.4 x 213.3 cm, © Pushpamala N.

Ideological and political struggles and art often converge and fuel one another, offering each visibility and expressive power. Born in the second half of the twentieth century, postcolonial studies are a critical reaction to the legacy of Western hegemony. They propose historical re-readings of the ways of life and traditions of civilisations that existed before this imperialism. In this context, artists have found the key to these readings and give rise to new ideas, while allowing new figures to emerge.

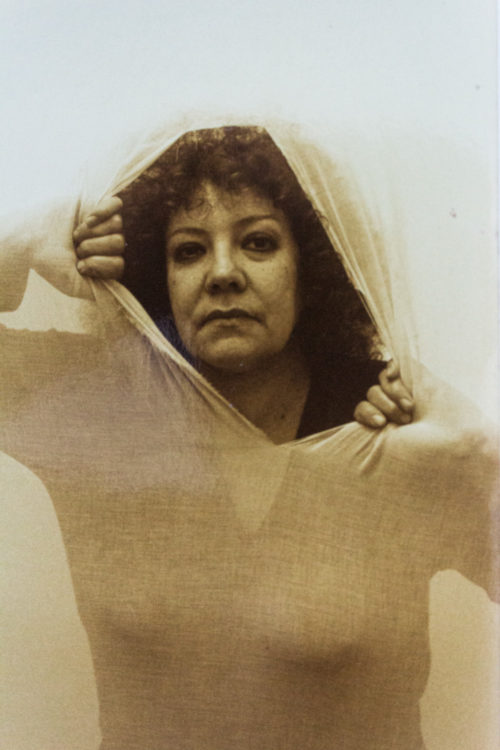

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the black activist and female artist Augusta Savage (1892-1962) sculpted the faces of her comrades in clay and became an emblem of the Harlem Renaissance, a movement to restore African-American culture during the interwar period. During the 1960s Gazbia Sirry (born in 1925) made her work a bias of critical observation of the political universe of contemporary Egypt. Today, Rebecca Belmore (born in 1960), renews postcolonial demands. She denounces the perpetuation of racialised stereotypes motivated by the tourism industry in Canada by highlighting the violence of these clichés and questioning the alienation of one culture by another. Archives, a tool of the historian, invite themselves into creations as a guarantee of authenticity, but also as a witness to the violence of the past. To speak about the narrative of white domination and to shed light on the present, Berry Bickle (born in 1959), a white Zimbabwean artist, uses these traces of the past in connection with a symbolist dialectic to address the suffering and the prospects for liberation in her country. Others appropriate documents to change their destination and perception. From the 1990s in India, Pushpamala N. (born in 1956) has staged cultural prejudices to denounce and deride them in her photographs, which resemble exotic and folkloric images that could be found on postcards at the beginning of the twentieth century. Malala Andrialavidrazana (born in 1971) focuses her work on memory, which she documents by meeting the inhabitants of the Indian Ocean. Thus, by writing her own history, she seeks to rediscover the ancestral traditions that have not given way to Western imperialism offering keys to a sociological reading of these territories.

For some, creation is a means of asserting new identities, a quest that already existed at the beginning of the 20th century. After the Mexican revolution, María Izquierdo (1902-1955) worked for a time with the muralists who created didactic frescoes. The painter began a reflection with them on art and the enhancement of their cultural identity. Irma Stern (1894-1966), a white South African creator, documented in her notebooks the daily essence of African life, which she deplored as a victim of colonisation, urbanisation and capitalism. Lubaina Himid (born in 1954) questions the marginalization of the African diaspora in society and in contemporary art and actively participates in the recognition of black women within British Black Art. Today, Pélagie Gbaguidi (born in 1965), works on memory transmission that links the past, present and future in which she projects bodies washed of all social norms, gender, race. This representation of being, aberrant for our societies, makes the present universal and restorative. It is through the re-appropriation of traditional rituals and ceremonies that Australian Phyllis Thomas Booljoongali (1940-2018) reaffirms her Aboriginal identity.

Postcolonial considerations, like those on gender, permeate all strata of the art world and push institutions to join in as well. This gives rise to events such as the symposium “What is a Post-Colonial Exhibition?” which took place on 25 May 2012 at the Framer Framed in Amsterdam. Another example is Okwui Enwezor’s The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition, published in 2003.

1925 — 2021 | Egypt

Gazbia Sirry

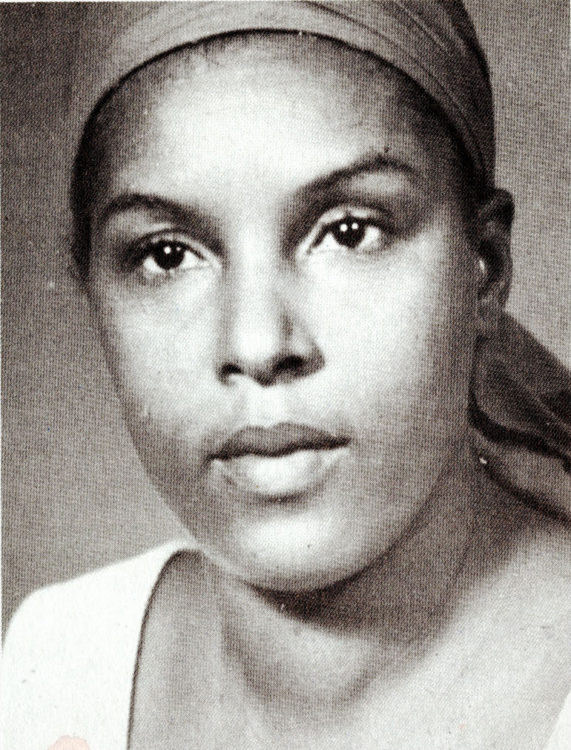

1960 | Canada

Rebecca Belmore

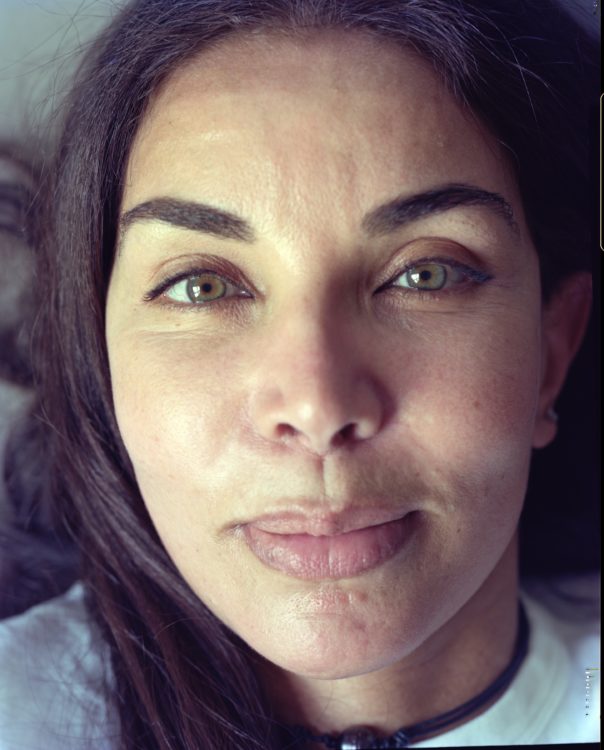

1956 | India

Pushpamala N.

1959 | Zimbabwe

Berry Bickle

1902 — 1955 | Mexico

María Izquierdo

1971 | Madagascar

Malala Andrialavidrazana

1954 | Tanzania

Lubaina Himid

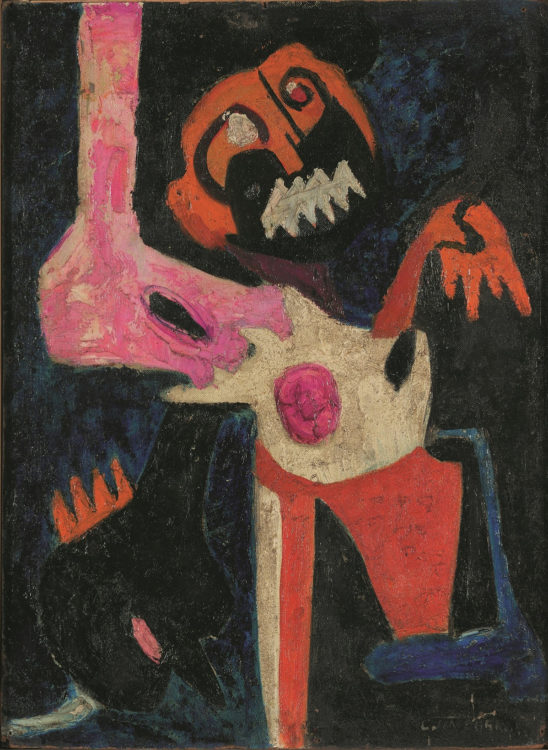

1894 — 1966 | South Africa

Irma Stern

1940 — 2018 | Australia

Phyllis Booljoonngali Thomas

1965 | Senegal

Pélagie Gbaguidi

1964 | South Africa

Berni Searle

1959 | United States

Renée Green

1924 — 2004 | Tunisia

Safia Farhat

1964 | Brazil

Adriana Varejão

1970 | Israël

Yael Bartana

1924 — 1989 | Egypt

Inji Efflatoun

1946 | Turkey

Gülsün Karamustafa

1964 | Australia

Fiona Foley

1972 | Lebanon

Lamia Joreige

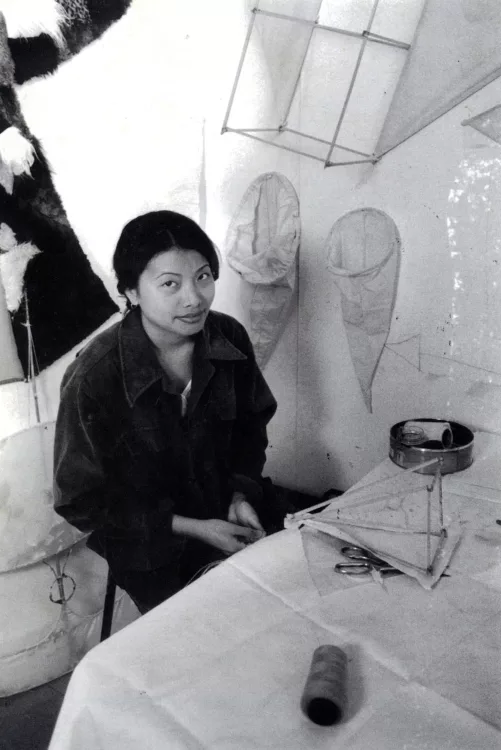

1971 | Malaysia

Yee I-Lann

1957 | Australia

Destiny Deacon

1970 | United States

Wura-Natasha Ogunji

1970 | Nigeria

Marcia Kure

1960 — 2008 | United Kingdom

Maud Sulter

1964 | New Zealand

Lisa Reihana

1971 | New Zealand

Ani O’Neill

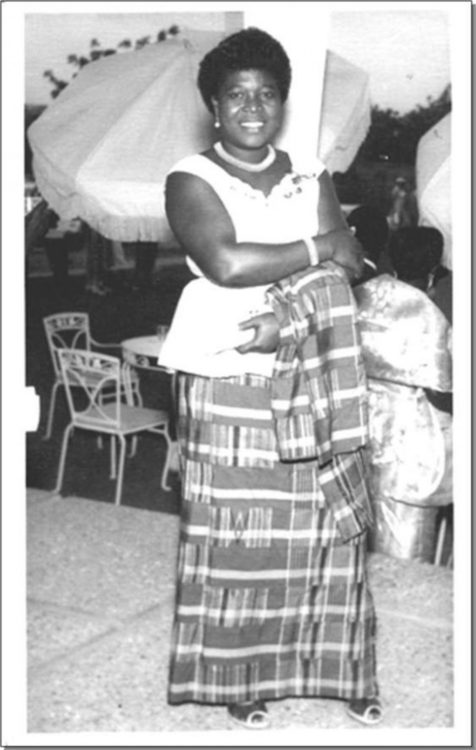

1942 | Nigeria

Colette Omogbai

1942 | New Zealand

Maureen Lander

1950 | New Zealand

Kura Te Waru Rewiri

1937 | New Zealand

Marilynn Webb

1956 | Morocco

Lalla Essaydi

1966 | Zambia

Agnes Buya Yombwe

1926 | United States

Betye Saar

1971 | United States

Mickalene Thomas

1962 | India

Sutapa Biswas

1935 — 1974 | Brazil

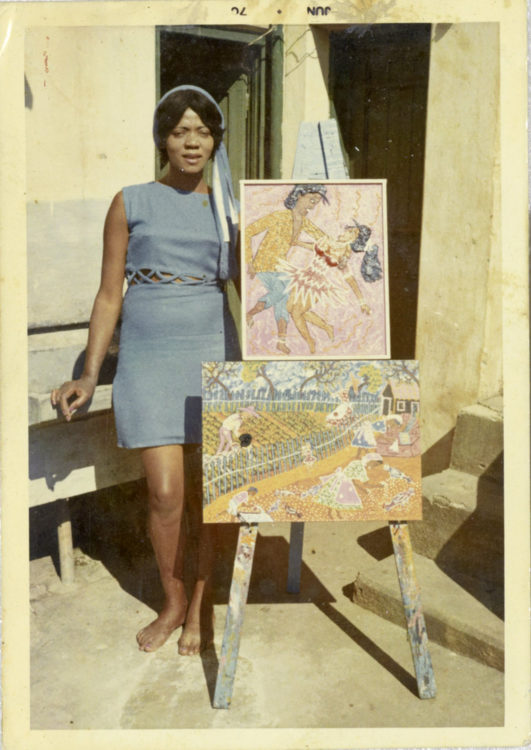

Maria Auxiliadora da Silva

1948 | United States

Joyce J. Scott

1960 | United States

Lorna Simpson

1948 | United States

Deborah Willis

1967 | United States

Simone Leigh

1961 | Jamaica

Jasmine Thomas-Girvan

1959 | Greenland

Jessie Kleemann

1965 | Australia

Julie Gough

1958 | Colombia

Doris Salcedo

1969 | United States

Kara Walker

1963 | France

Zineb Sedira

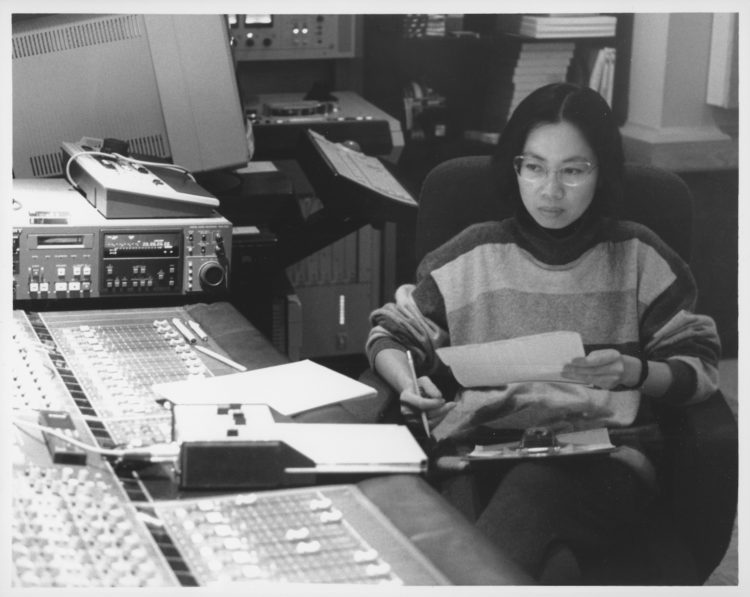

1959 | Japan

Yoshiko Shimada

1957 | United States

Cheryl Ann Bolden

1953 | Guadeloupe, France

Michèle Chomereau-Lamotte

1940 — 2024 | Philippines

Brenda Fajardo

1941 | United Kingdom

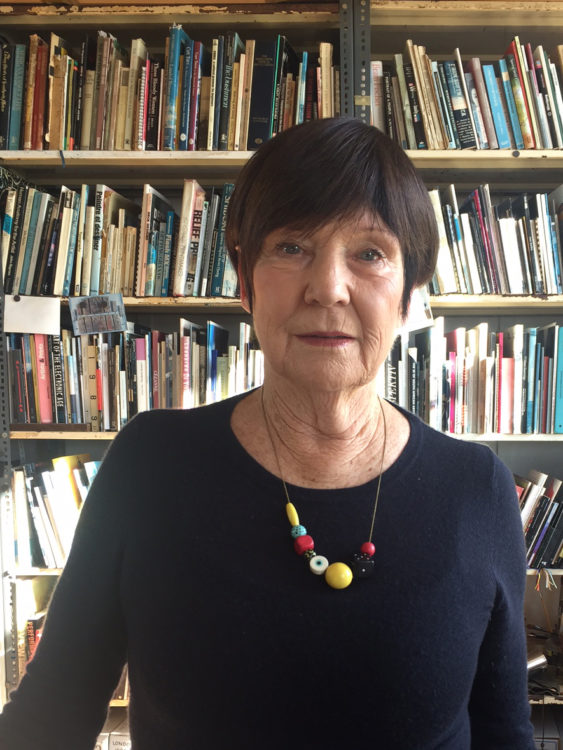

Sue Williamson

1959 | Australia

Judy Watson

1963 | Nigeria

Mary Evans

1944 | Martinique, France

Roseman Robinot

1964 | Martinique, France

Valérie John

1909 — 1981 | Martinique, France

Marie-Thérèse Julien Lung-Fou

1945 | Lebanon

Seta Manoukian (Ani Pema Drolma)

1966 | Netherlands

Patricia Kaersenhout

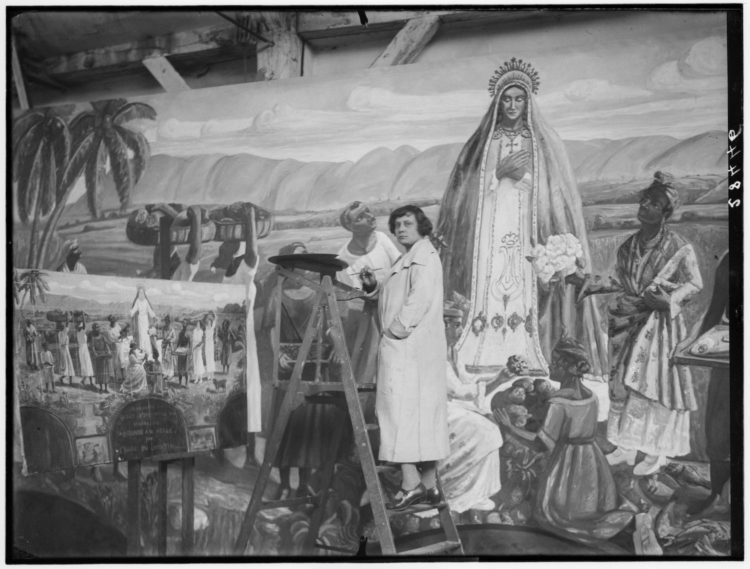

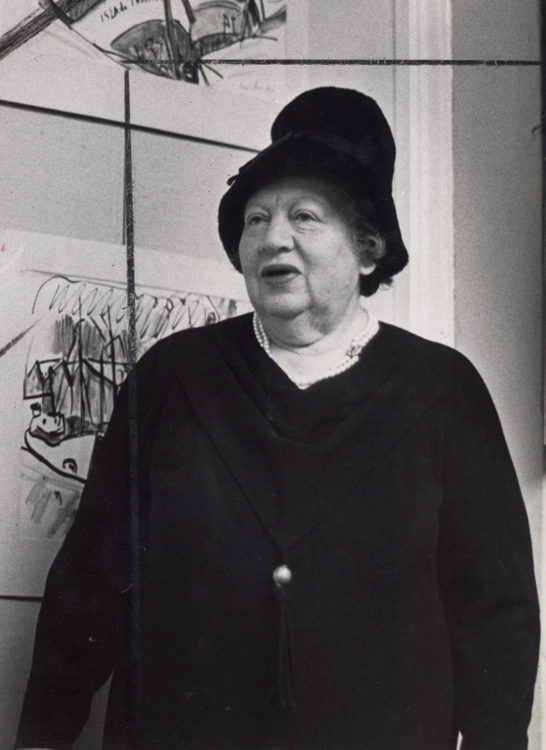

1899 — Netherlands | 1984 — Surinam

Nola Hatterman

1910 — 2004 | Martinique, France

Paule Charpentier

1967 | United States

Marie Watt

1971 | French Guiana

Nathalie Leroy Fiévée

1938 — 2015 | Uruguay

Nelbia Romero

1969 | United States

Nao Bustamante

1969 | Netherlands

Sara Blokland

1960 | United States

Coco Fusco

1947 | Mandatory Palestine

Efrat Natan

1969 | Guyana

Moira Pernambuco

1959 | Canada

Dana Claxton

1933 — 2023 | Algeria

Djamila Bent Mohamed

1969 | Russia

Louisa Babari

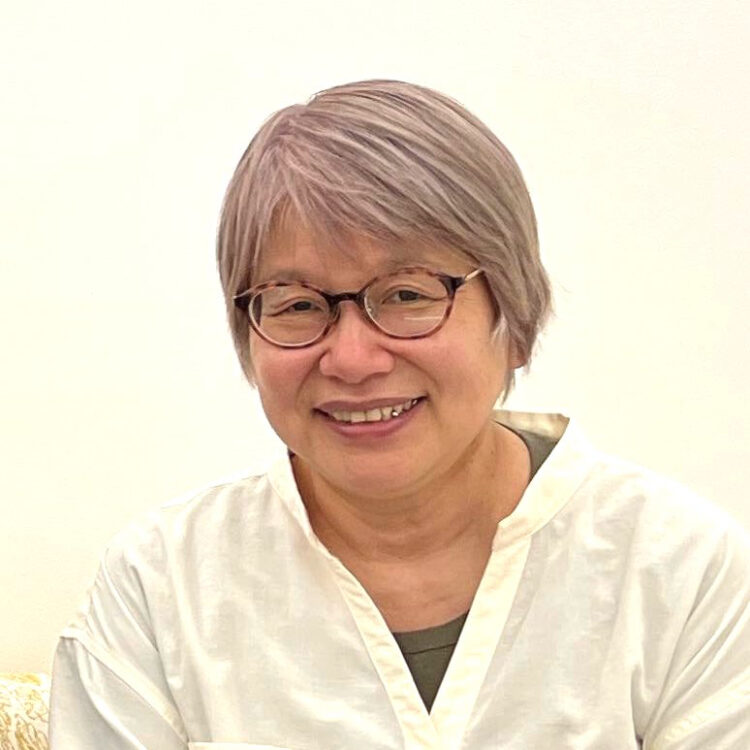

1927 — Singapore | 2020 —

Chen Cheng Mei

1969 | Canada

Skawennati

1934 — 1999 | Uganda

Estelle Betty Manyolo Sangowawa

1928 — Nigeria | 2003 — Cameroon

Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu

1962 — 2023 | Taiwan

HOU Lulu Shur-tzy

1973 | France

Katia Kameli

1933 — Haiti | 1988 — Canada

Rose-Marie Desruisseau

1952 | Vietnam

Trinh T. Minh-ha

1952 | United States

Elenora “Rukiya” Brown

1946 | Mexico

Guadalupe García-Vásquez

1973 | Netherland

Jennifer Tee

1951 | Singapore

Amanda Heng

1927 — Sierra Leone | 1996 — United Kingdom

« Olayinka » Miranda Burney-Nicol

1922 — 2015 | Ghana

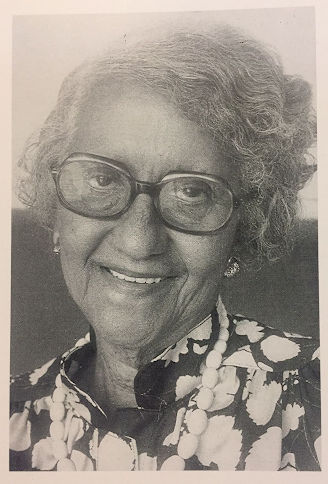

Theodosia Salome Okoh

1973 | Iraq

Sama Alshaibi

1960 | Uruguay

Mary Porto Casas

1973 | Australia

Yhonnie Scarce

1967 | Nigeria

Fatimah Tuggar

1971 | France

Yto Barrada

1974 | France

Isabelle Cornaro

1940 — Mandatory Palestine | 2022 — United Kingdom

Laila Shawa

1940 — 2021 | Zimbabwe

Helen Lieros

1970 | Netherlands

Iris Kensmil

1935 — Mandatory Palestine | 2016 — United Kingdom

Maliheh Afnan

1948 — Lebanon | 2019 — France

Jocelyne Saab

1974 | Guatemala

Sandra Monterroso

1959 | Cuba

María Magdalena Campos-Pons

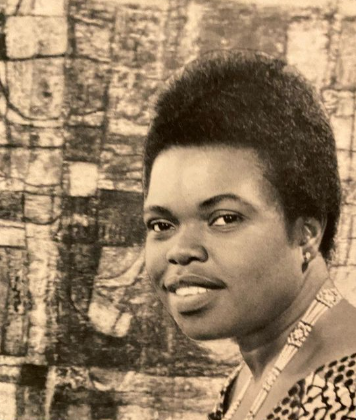

1922 — 2014 | Peru

Victoria Santa Cruz

1965 | Haiti

Barbara Prézeau Stephenson

1970 — 2014 | Singapour

Juliana Yasin

1959 | Singapore

Suzann Victor

1956 | Syria

Laila Muraywid

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.