Jana Sterbak

Borja-Villel Manuel (dir.), Velleitas : Jana Sterbak, (exh. cat.), Musée d’Art Moderne, Saint-Étienne (1995); Antoni Tàpies Foundation, Barcelona (1995); Serpentine Gallery, London (1996), Barcelona, Fundació Antoni Tàpies, 1995

→Godmer Gilles (dir.), Jana Sterbak, (exh. cat.), Museum of Contemporary Art, Montréal (14 Febrary – 20 April 2003), Montreal, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2003

→Cohen Françoise (dir.), Jana Sterbak, Condition contrainte (exh. cat.) Carré d’Art-Museum of Contemporary Art, Nîmes (20 October 2006 – 7 January 2007), Arles, Actes Sud, 2006

Project Room, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1992

→Jana Sterbak, Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montréal, 14 Febrary – 20 April 2003

→Sterbak, Musée Montserrat, Montserrat Abbey (Spain), 2014

Canadian visual artist.

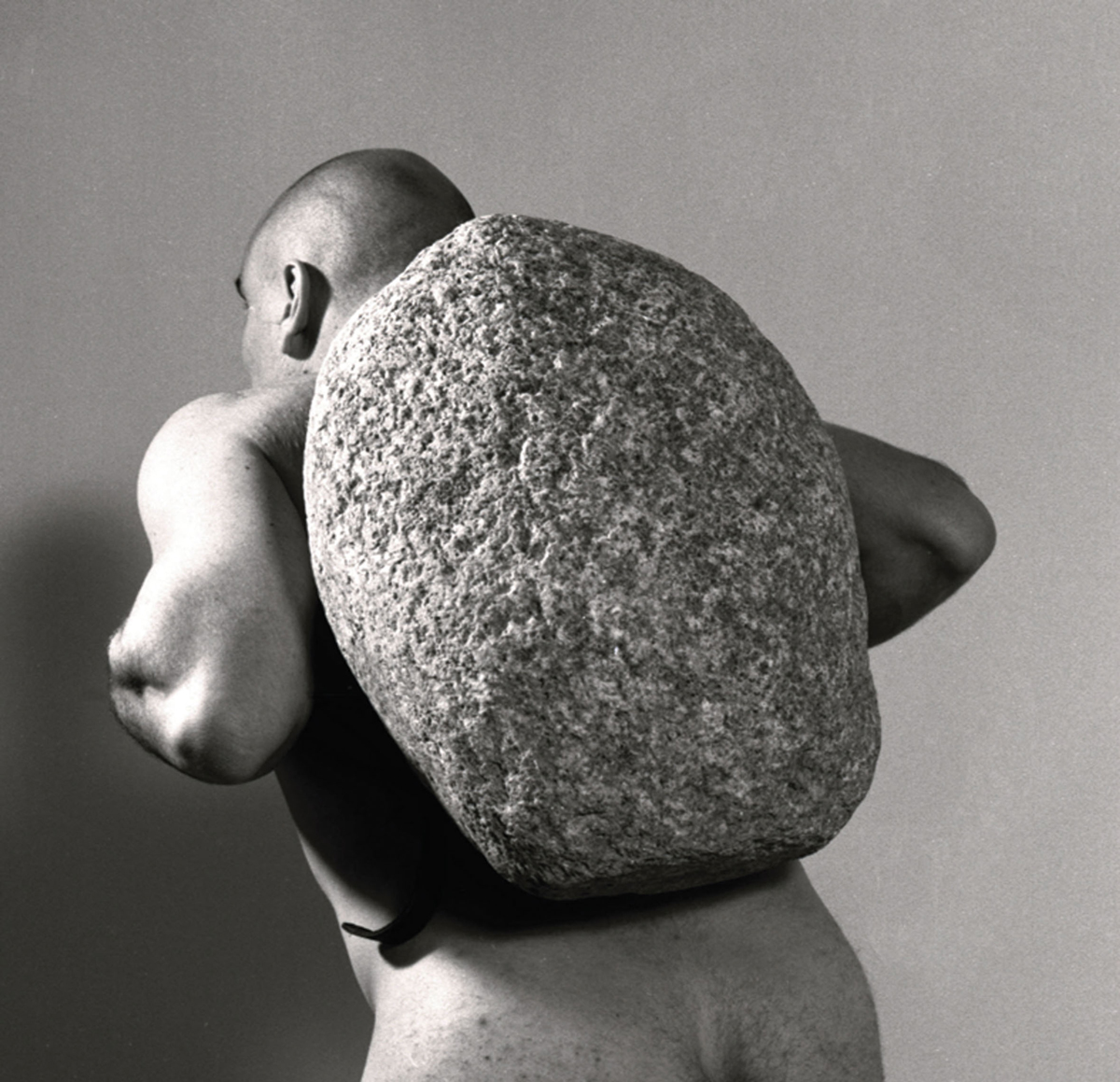

In 1968, Jana Sterbak left Czechoslovakia with her parents and settled in Canada. Graduating from Concordia University in Montreal in 1977, she created a body of work that was to be the subject of many monographic exhibitions. In 2003, she represented Canada at the Venice Biennale. From the late 1970s, she became interested above all in the human body, which she presented in forms that hindered freedom of movement: sometimes endowed with prostheses or subjected to challenging physical efforts. In Cones on Fingers (1979), the artist coiled a metre of measuring tape around the fingers of each hand, thus forming five elongated cones; Measuring Tape Cones (1979) presents a variant of the cones. These prostheses, while highlighting the grace of the curve formed by the wrist, reduce the hand to a simple aesthetic object. All movement becomes impossible. With Sisyphus (1991), she devised a cage with a rounded and unstable base, in which the caged individual must perform a strange choreography in order to find his balance. Clothing also becomes prostheses that alienate or transform the body: the two sewn-together sleeves of Jacket (1992) form just one, prohibiting the wearers from revealing their hands; Hairshirt (1992), designed to be worn by a woman, is covered in hair, thus imitating the male torso; Inhabitation (1983) borrows the shape of a pregnant woman’s belly in synthetic material, enabling a man to experiment with the deformation of the body during pregnancy. All of this equipment confers a captivating monstrosity on the body, between attraction and repulsion. For the 50th Venice Biennale, she created a video that was presented on several screens, From Here to There, a series of sequences filmed in Venice and Canada by Stanley, a dog, onto which a small camera was attached; the spectator thus discovers the city of the Doges and the banks of the Saint Laurence River from 35 centimetres above the ground, through the eyes of a Jack Russell terrier. The dog-cam was used again in 2005 for Waiting for High Water, a film presented that year at the Prague Biennale. These two installations were brought together in 2006, at the Artium Museum in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, for the occasion of a solo exhibition by the artist.

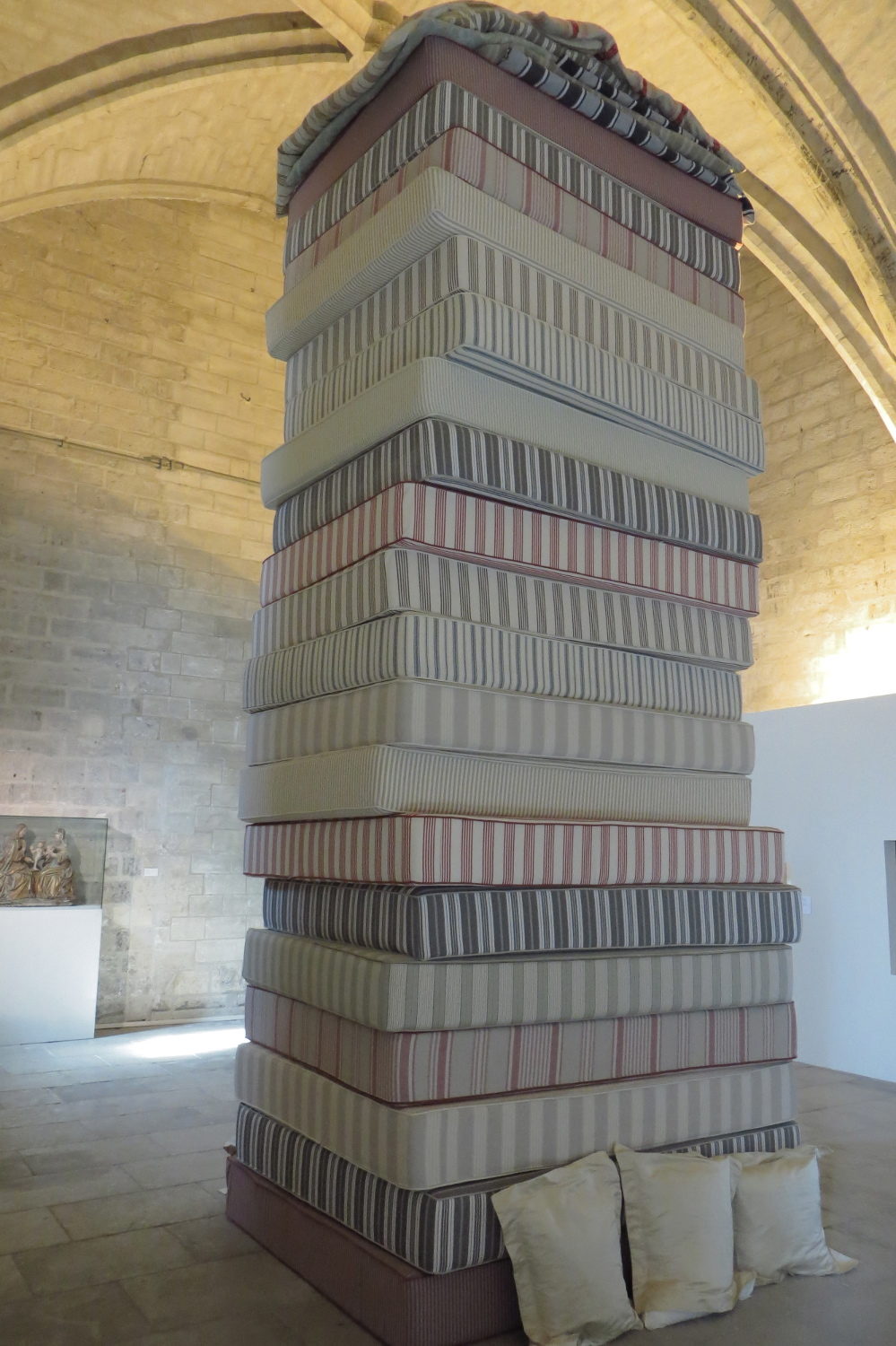

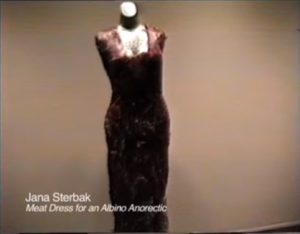

In a different register, she also experiments with the reappropriation of materials; for Bread Bed (1979), she placed a bread mattress on a bed, while Chair Apollinaire (1996) presents an armchair upholstered with meat. Occasionally, the perishable nature of the materials used adds a memento mori dimension to the sculptures, as with Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anocrectic, a dress made of meat: recreated for each new exhibition based on the original pattern, the garment is now shown on a tailor’s bust made of wood and cloth, alongside the photograph of its original model, worn at the time by a young woman. The theme of the vanitas is also explored in Catacombs (1992): a skull and the bones of a human skeleton made out of chocolate. The domestic sphere has inspired much of her work, including furniture: House of Pain: A Relationship, a project designed in 1987, represents a house with an empty centre, through which “visitors” must follow an imposed pathway, which skirts around the periphery, with each room containing a new form of suffering – once they have set out, it is difficult for them to turn back. The fictional adventure of the visitors in this installation is similar to the experience of real visitors contemplating J. Sterbak’s works: anxiety is mingled with the irrepressible attraction that each new work provokes and that invites the viewer to delve a little further into the artist’s world. In 2011, the home gave way to the cosmos: shown at the Musée Réattu in Arles, Planetarium consisted of 15 spheres of monumental glass created at the Centre International de Recherche sur le Verre et les Arts Plastiques de Marseille; its form is inspired by the glassblowers’ gesture, changing magma into spheres from their first exhale and thus transforming matter into a planet, like the primordial act of a creator-god.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Jana Sterbak, Robe de chair pour albinos anorexique

Jana Sterbak, Robe de chair pour albinos anorexique