Katharina Fritsch

Katharina Fritsch, exh. cat., New York, Dia Center for the Arts, (April 1993 – April 1994), New York, Dia Center for the Arts, 1994

→Vischer Theodora (ed.), Katharina Fritsch, exh. cat., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel (1995-1996), San Francisco, Museum of Modern Art, 1996

→Blazwick Iwona (ed.), Katharia Fritsch, exh. cat., Tate Modern, London; Kunstsammlung im Ständehaus, Düsseldorf, (2001 – 2002), Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 2002

Katharina Fritsch, New York, Dia Center for the Arts, April 1993 – April 1994

→Katharina Fritsch, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Basel, San Francisco, 1995-1996

→Katharia Fritsch, Tate Modern, London; Kunstsammlung im Ständehaus, Düsseldorf, 2001 – 2002

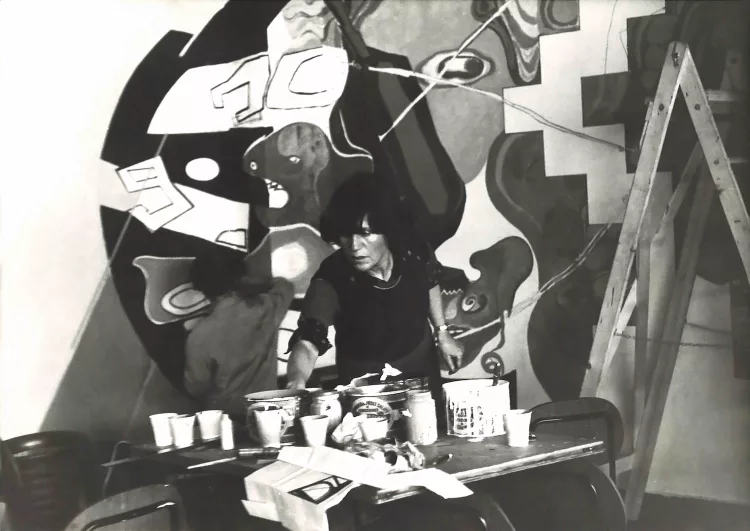

German sculptress and visual artist.

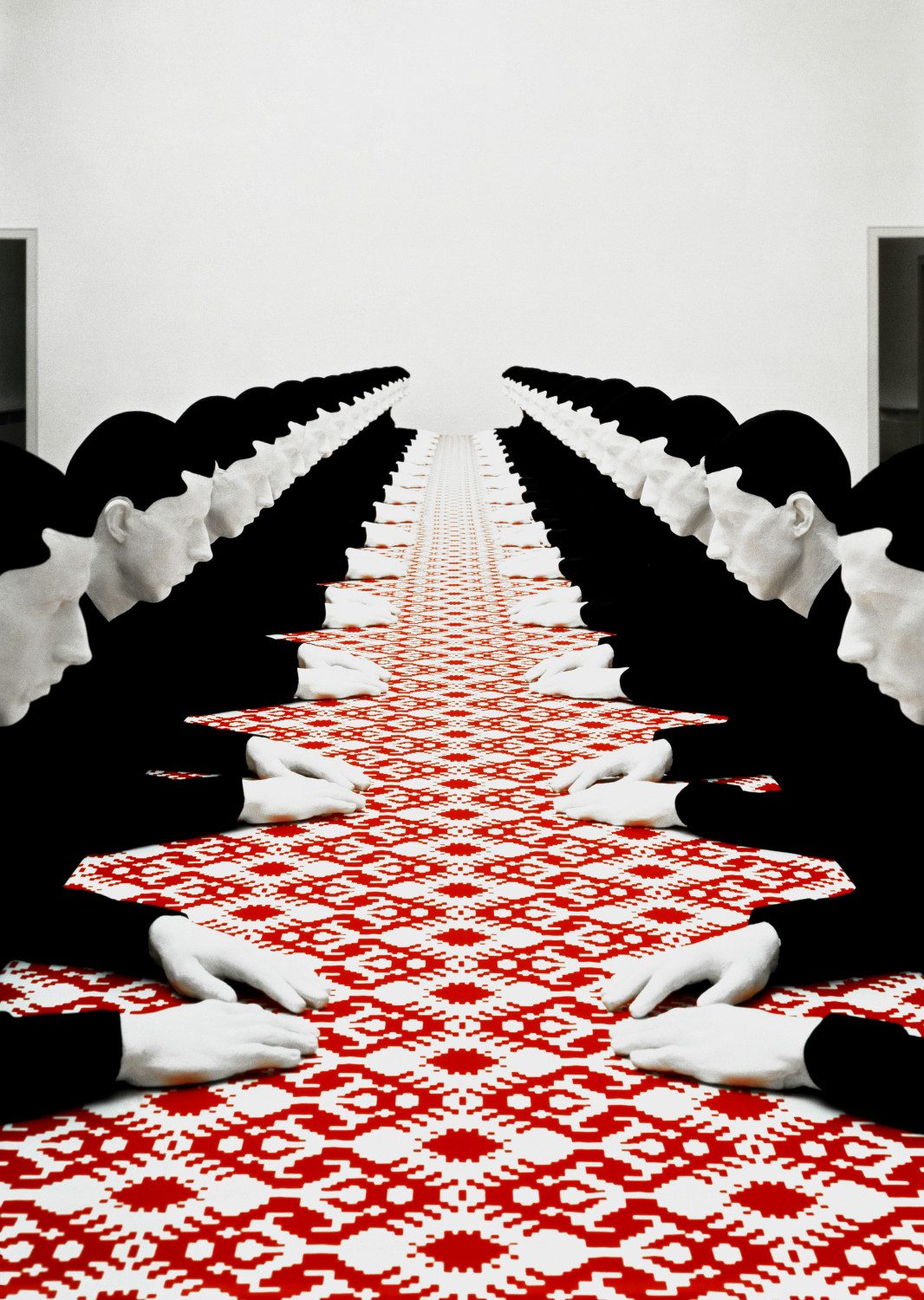

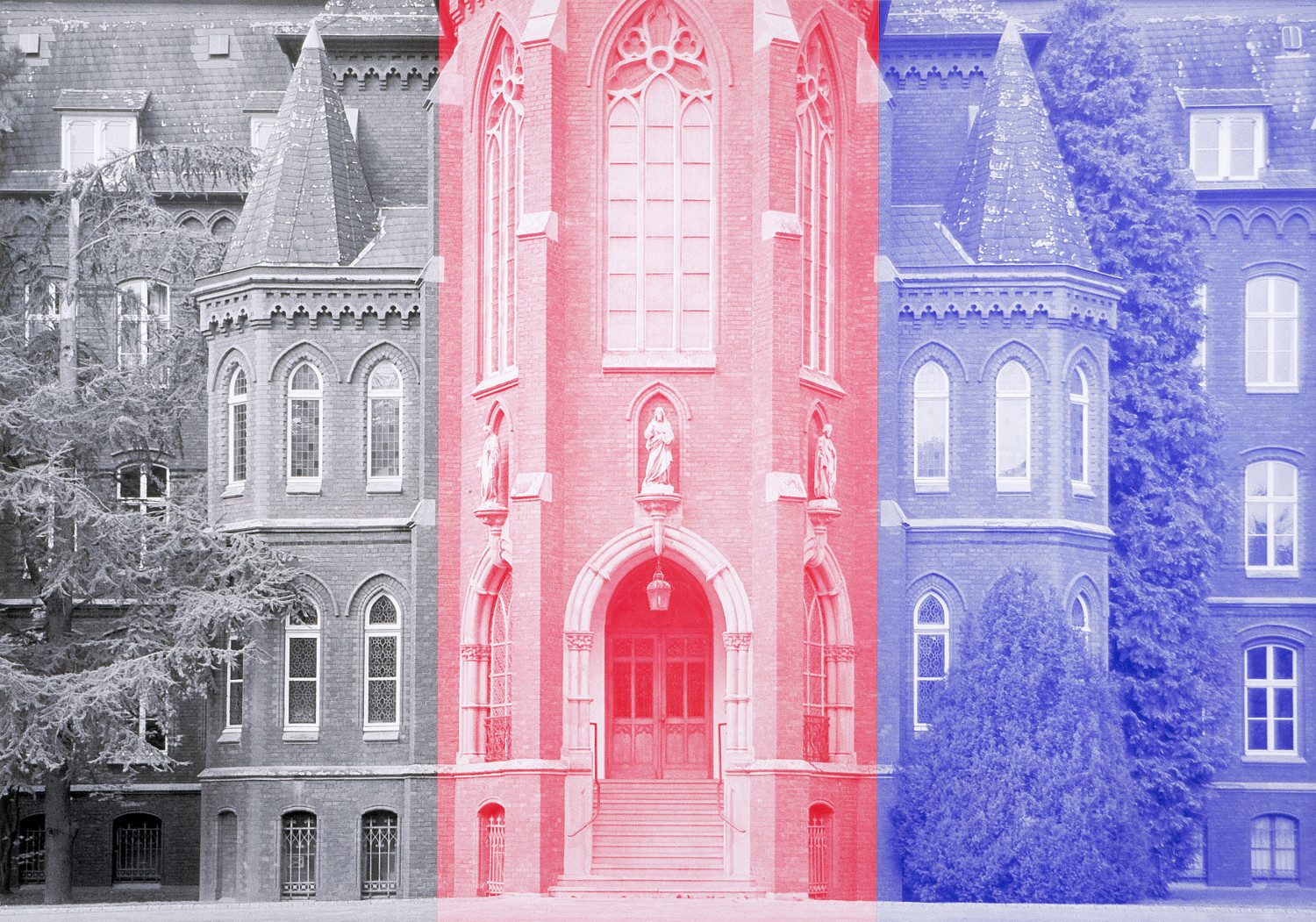

Katharina Fritsch was trained at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Arts Academy) between 1977 and 1984. And while she creates a wide variety of works – objects, images, sound works – she is especially known for her sculptures. All of her utilitarian objects – umbrellas, bottles – or symbolic objects – skulls, crosses, the tower of Pisa – are executed with incredible technical skill. The artist creates moulds from which the works are cast out of polyester, plaster, or aluminium. While these exact and precise shapes leave no doubt as to the nature of the objects, they nonetheless have a troubling effect, since scale is not necessarily respected, and the pieces are covered in a single solid colour that makes them seem unreal. For example, it could be a tongue-in-cheek rendering of a statuette of the Madonna like those found in Lourdes, but in fluorescent yellow, or the silhouette of a monk entirely covered in black. The artist thus recasts objects and characters that then lose their individuality and familiarity to become abstractions. From this emerges a sense of unease, these shapes acting on the mind like recollections. Taken from various sources (the everyday world, pop culture, art history, fairy tales), they belong to a collective memory, which is then more or less consciously rekindled in the spectator.

One of her best-known creations, Rattenkönig [The Rat King, 1993], presents the nightmarish scene of a circle of giant rats whose tails are tied together, the origins of which can be traced back to Northern European fairy tales. Tischgesellschaft [Dinner, 1998] consists of a long rectangular table around which men are seated, all identical, which recalls both an image of the Last Supper from the history of art as a family dinner as seen by a child or a meeting taking place during an international convention. The artist often uses repeated patterns which, arranged geometrically inside a circle or grid, give the impression of psychotic proliferation. In 1995, she represented Germany along with Martin Honert and Thomas Ruff at the 46th Venice Biennale. In 1996 she was featured in a monographic exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, then in 2001 at the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art and the Tate Modern in London. In 2009 she was exhibited by the Kunsthaus Zurich, the Museum for Modern Art.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Katharina Fritsch, Parole aux artistes, Centre Pompidou

Katharina Fritsch, Parole aux artistes, Centre Pompidou