Lygia Clark

Lygia Clark, exh. cat., Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona ; MAC, galeries contemporaines des musées de Marseille ; Fundação de Serralves, Porto ; Société des expositions du Palais des beaux-arts, Bruxelles (1997-1998), Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 1998

→Diserens Corine (ed.), Lygia Clark : de l’œuvre à l’événement, exh. cat., musée des beaux-arts, Nantes (8 October – 31 December 2005), Nantes; Dijon, musée des beaux-arts de Nantes; Les presses du réel, 2005

→Bulter Cornelia (ed.), Lygia Clark : the abandonment of art, 1948-1988, exh. cat., Museum of modern art, New York (10 May – 24 August 2014), New York, Museum of Modern Art, 2014

Lygia Clark, Museu de Arte Contemporanea da Universidade, Sao Paulo, Brazil , 1987

→Lygia Clark, De l’œuvre à l’événement, Nous sommes le moule. A vous de donner le souffle, musée des beaux-arts, Nantes, 8 October – 31 December 2005

→The abandonment of art, 1944-1988, Museum of Modern art, New-York, 10 May – 24 August 2014

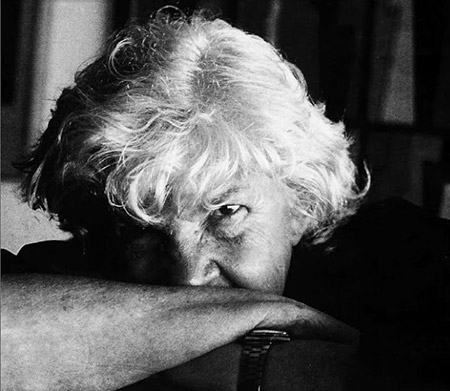

Brazilian painter, sculptor and psychotherapist.

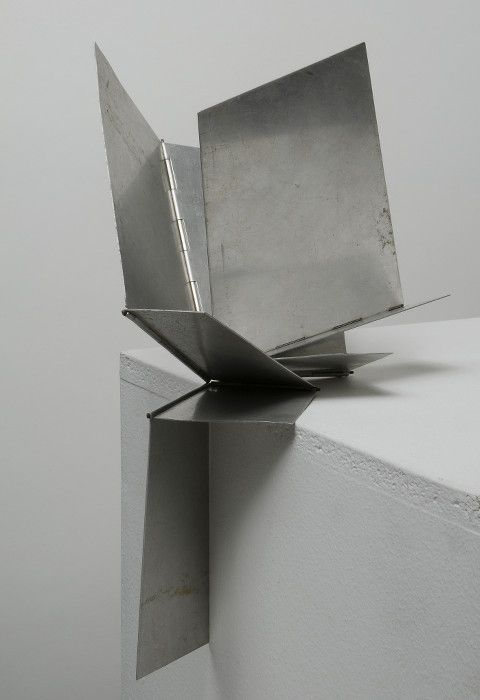

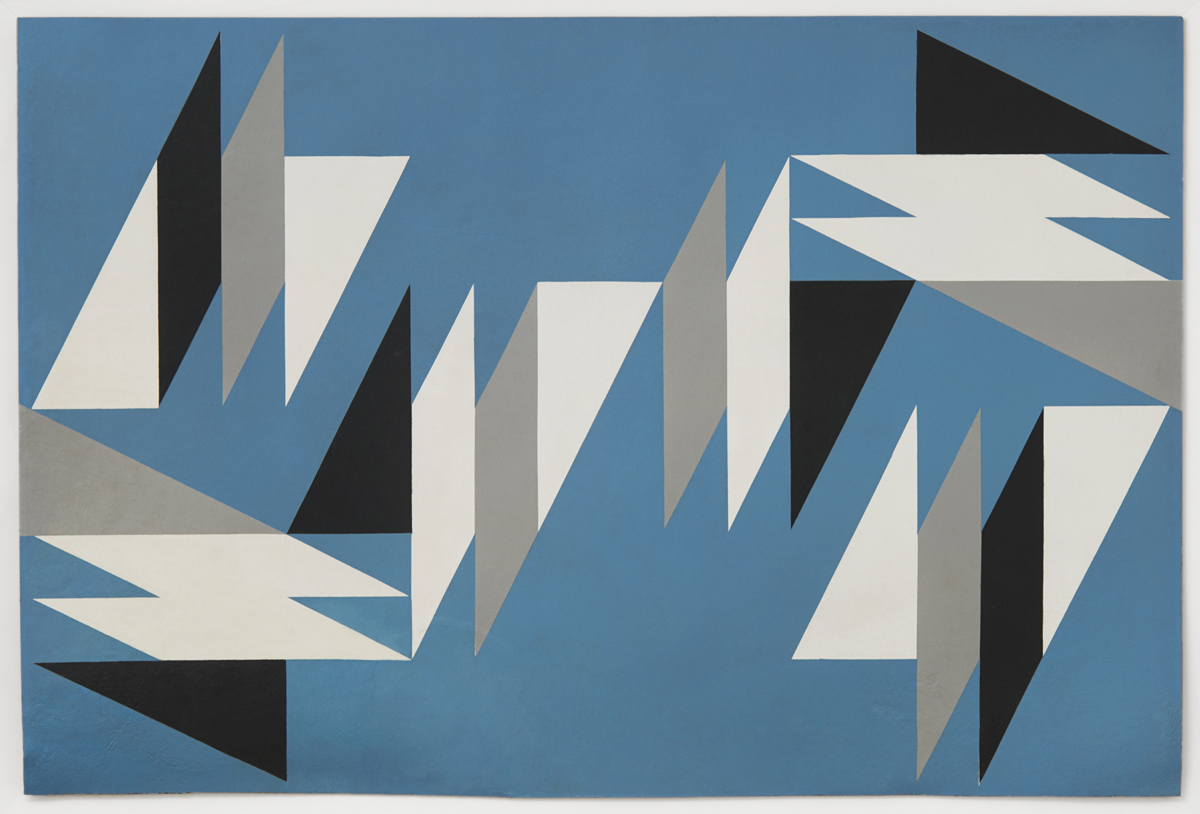

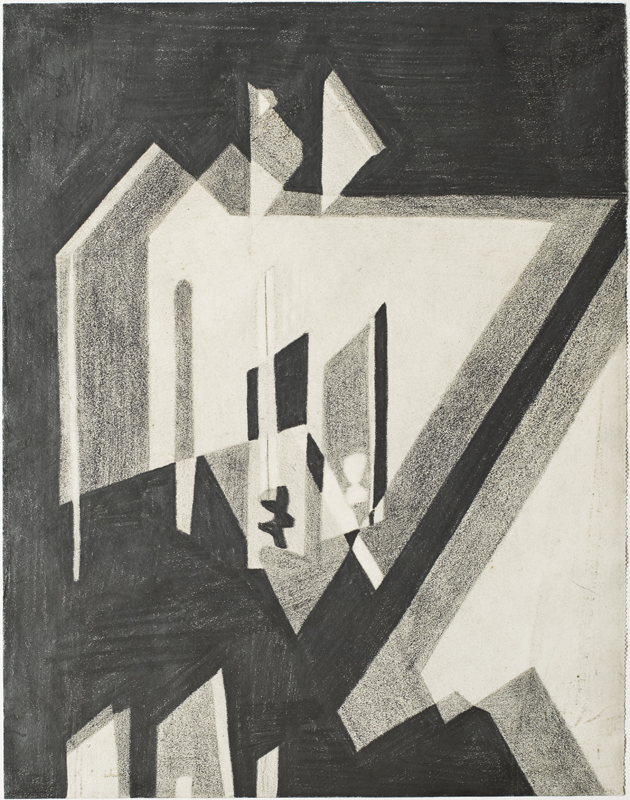

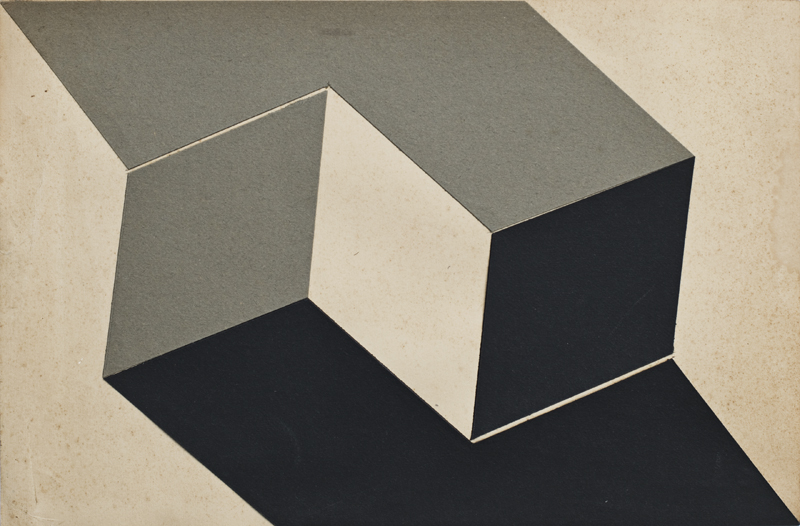

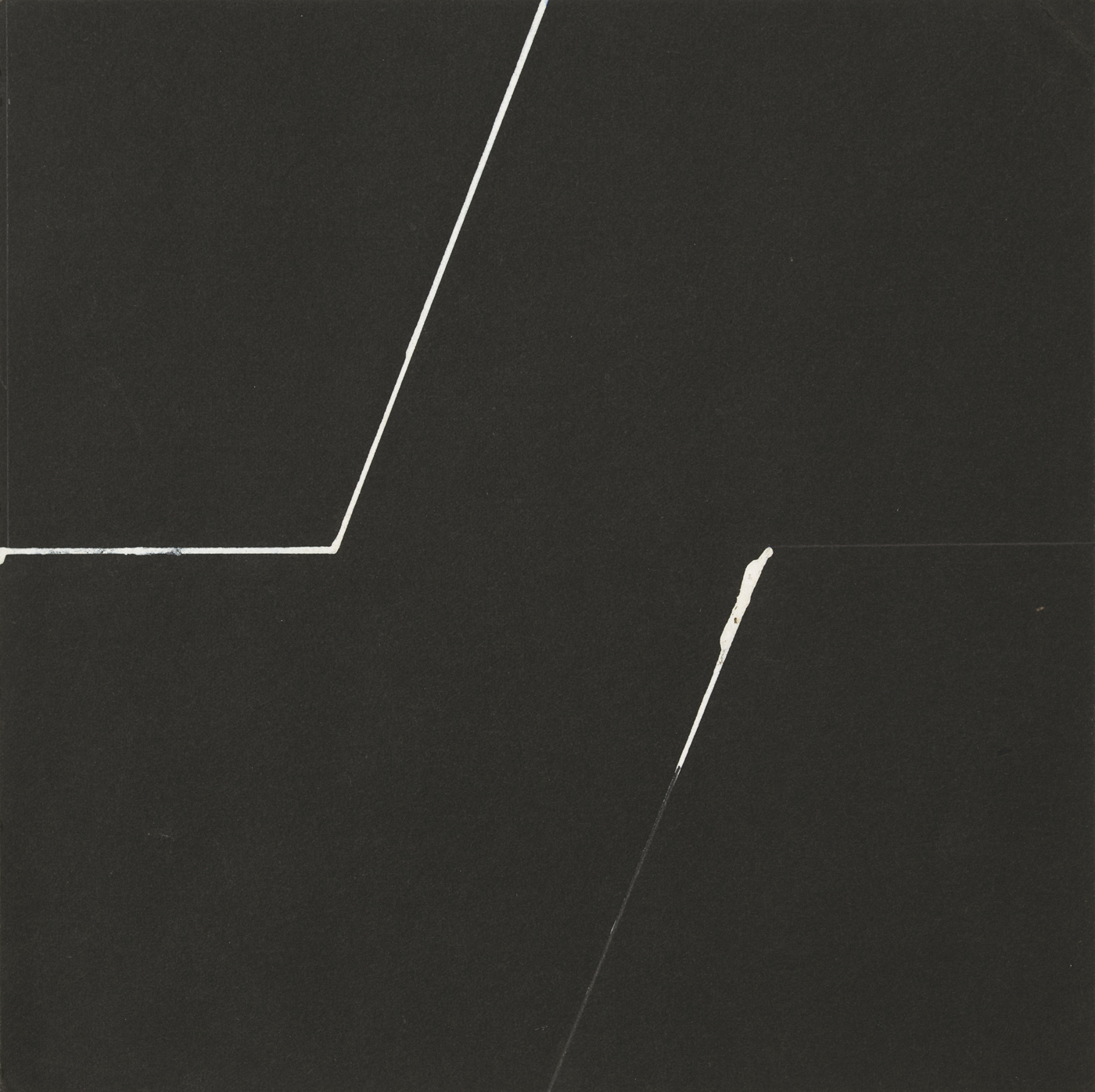

Married at the age of eighteen, Lygia Clark led a normal middle-class life until her divorce in 1947, then moved to Rio de Janeiro to take up art. Her training in painting began under Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994), a famous landscape architect, and continued in Paris between 1950 and 1952 alongside Fernand Léger (1881–1955) and Árpád Szenes (1897–1985). When concrete art – an abstractionist movement strongly derived from Russian constructivism – dominated the visual arts in South America, her painting concerned itself with the concretist exploration of the elements in the pictorial space, paying particular attention to the interstices between planes, especially the interphase between the canvas and the frame, which Clark would treat as a plastic element in its own right. In 1959 a group of artists based in Rio de Janeiro signed the Neo-Concrete Manifesto in response to the formalist and rationalist intransigence of concretism. Lygia Clark became one of the central figures in this dissident reaction and advocated a more organic and personal approach to the creation of a work of art. She claimed, “So-called geometric forms totally lose the objective character of geometry to turn into vehicles for the imagination”. In her series Bichos (“creatures”, 1960), made of sheets of polished metal joined by hinges, the viewer becomes the agent of the work in giving it a new form by altering the spatial relationships between the sheets. In the same year Clark taught visual arts at the national institute for the education of the deaf, where she created works that increasingly required the interaction of their viewers and which moved towards the de-substantiation of art. Caminhando (“walking”, 1964) is emblematic of this transition: a strip of paper is cut longitudinally by a participant until a Moebius Strip is created. “The work consists in the creation of the work itself; you and it become indissociable”, she declared.

During the 1960s she considered that the role of the artist was to propose and channel experiences of this sort with the aim of exploring perceptive, mnemonic and emotional phenomena. Examples of works with this purpose were: Luvas sensoriais (“sensorial gloves”, 1968), an invitation to the participant to rediscover the sense of touch; O Eu e o tu, série roupacorpo- roupa (“the I and the you, clothing-bodyclothing series”, 1967), in which a man and a woman are asked to wear industrial suits created by the artist that have the aim of inculcating “feminine” sensations in the man and “masculine” sensations in the woman; A Casa é o corpo, labirinto (“the house is the body, labyrinth”, 1968), a tunnel 8 metres long that the participant walks through, pushing successively through spaces titled “Penetration”, “Ovulation”, “Germination” and “Expulsion”. The viewer’s participation and the utilization of the material support to engender something beyond the immediate experience were fundamental themes in Clark’s practice, and were associated during the 1970s with a discourse based on the theories of Melanie Klein and Donald Winnicott. This period was a turning point in the work of Lygia Clark towards therapeutic art, and towards the end of her life she considered her practice as being more in the realm of psychoanalysis than art. Between 1970 and 1975 she ran a seminar on the phantasmatic nature of the body at the Centre Saint-Charles in the Université Paris 1-Panthéon-Sorbonne, in which she asked her students to perform group exercises that were a continuation of her exploration of the psyche, such as Túnel, Canibalismo and Baba antropofágica (“anthropophagic slobber”), in which she conceived various rituals designed to trigger symbolic experiences.

Following her return to Brazil in 1976, her art continued to develop on the edge of the art world but her activities, which were then purely psychotherapeutic, stimulated little interest among psychologists or psychiatrists. The works in her last series, Objetos relacionais (“relational objects”) were conceived for therapeutic purposes and had the purpose of regressing the participant so as to bring to the surface sensations recorded in the body’s memory at a time before the acquisition of language. It was only as from 1980 that her work received broad international recognition. Retrospectives celebrate its multi-faceted character (de-substantiated work, work as process, work-medium) and emphasize the critical nature of Lygia Clark’s interest in a certain fetishist aspect of contemporary art, with the aim of establishing and exalting the figures of the artist and the work of art.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988

Lygia Clark: The Abandonment of Art, 1948–1988  Peter Eleey discusses Lygia Clark’s Bicho

Peter Eleey discusses Lygia Clark’s Bicho