María Freire

Franco, Ana M., « Fighting Stereotypes: The Industrialist Aesthetic in María Freire’s Concrete Production », New York, Latin American Collection Fellowship, Cisneros Institute, Museum of Modern Art, 2021

→Peluffo Linari, Gabriel, María Freire: Vida y deriva de las formas, Montevideo, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura / Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, 2017

→Pérez-Barreiro, Gabriel, María Freire, São Paulo, Cosac & Naify, 2001

Sur moderno: Journeys of Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019–September 12, 2020

→Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction, Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 15–August 13, 2017

→María Freire. Forma y color, Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, Montevideo, March 15–May 15, 2016

Uruguayan sculptor and painter.

María Freire studied at the Círculo de Bellas Artes de Montevideo with José Cúneo (1887–1977) and Severino Pose (1894–1964), and at the Universidad del Trabajo del Uruguay. In 1944 she attended the studio of Joaquín Torres García (1874–1949), but this well-known figure failed to capture her interest. As she explained in a 2006 interview in the Uruguayan magazine Galería, she considered him too “vain”.

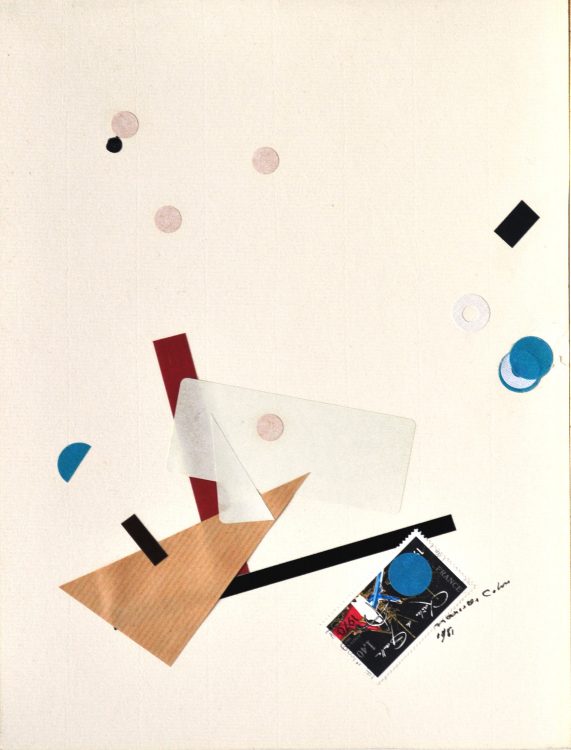

In 1944 M. Freire moved to Colonia del Sacramento to work as a secondary education drawing teacher and art history teacher in the architecture preparatory programme. She lived alone in a hotel, defying the social conventions of the times, and becoming friends with artists like Rhod Rothfuss (1920–1969), later a member of the Madí group, who was also working as a teacher in the city. In 1951, when she returned Montevideo, she founded the Grupo de Arte No Figurativo together with the artist José Pedro Costigliolo (1902–1985), whom she married the following year. The group’s orientation was pure abstraction, in distinction to the spiritualism and craft aesthetics that characterised the Universal Constructivism of Torres García and his studio disciples.

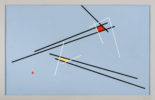

M. Freire’s highly innovative sculptures make distinctive use of industrial materials such as acrylic, iron and sheet metal, and the inclusion of moving parts. She was also drawn to African and Pacific Island art, as can be seen in her bronze piece Máscara [Mask, 1948]. During the 1950s she worked with engineers at the Kraft-Imesa plant to make sculptural work using acrylic, notably Construcción en acrílico y bronce [Acrylic and bronze construction, 1953], while continuing to develop her painting under the influence of Russian Constructivism, Brazilian Concretism, and the Madí and Arte Concreto-Invención groups. As with her sculpture, her painting is also marked by the use of unconventional materials like pyroxylin enamel applied with a blowtorch and latex paint, notably in her A.B.N. (1957) and V.N.A. (1957).

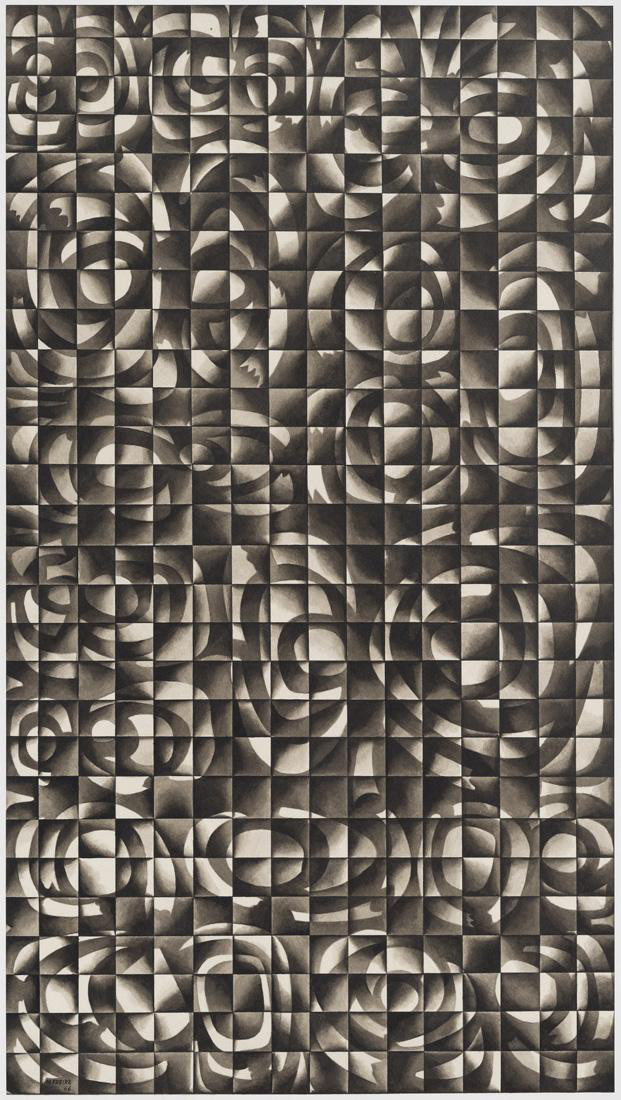

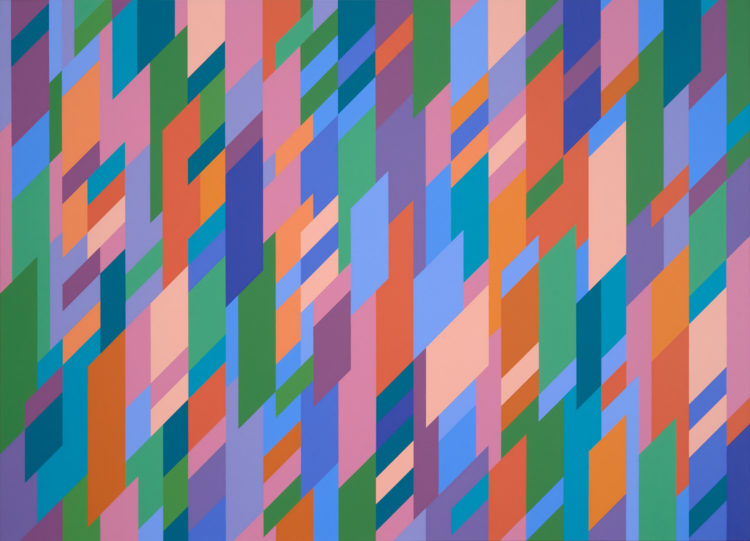

She abandoned sculpture in the mid-1950s to focus exclusively on painting. She explored chromatic vibration and the repetition of forms in her series Sudamérica [South America, 1958–1960], Córdoba (1965), Capricornio [Capricorn, 1975] and Vibrante [Vibrant], made during the 1970s. After her husband’s death in 1985 she once again turned to sculpture. Starting in the first years of the 21st century, she made large-scale sculptures destined to be installed in public spaces. She remained prolific until her death in Montevideo at the age of 97.

Some of her more outstanding solo shows were held at the Museo de Arte Moderno de San Pablo (1956), the Museo de Arte Moderno de Río de Janeiro (1957) and the Unión Panamericana in Washington, D.C. (1966). The IV Bienal del Mercosur featured a tribute to her career in 2003, and a retrospective of her work took place at Museo de Bellas Artes Manuel Blanes de Montevideo in 2016. Her work is to be found in collections including the Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales de Uruguay, the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros collection, MoMA and the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA).

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023