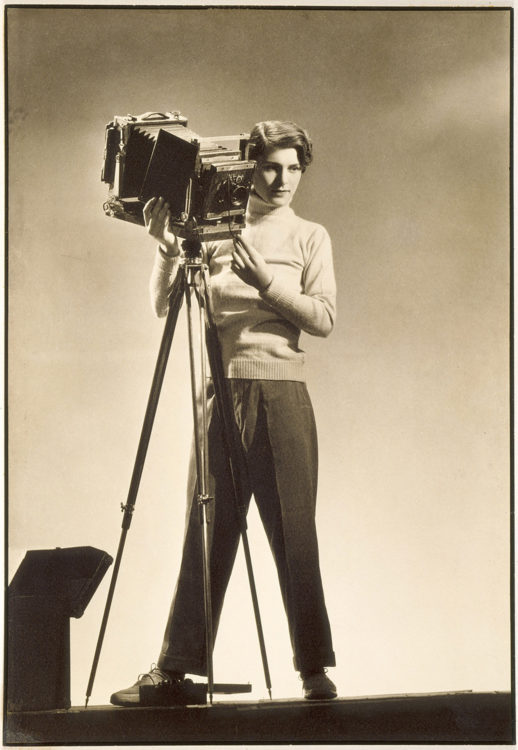

Margaret Bourke-White

Rubio Oliva María, Quimby Sean M., Bermejo Ev (ed.), Margaret Bourke-White: Moments in History, exh. cat., Martin-Gorpius-Bau, Berlin; Preus Meseum, Horten; Fotomuseum, The Hague; Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY (2013–2015), Madrid, La Fábrica, 2014

→Goldman Rubin Susan, Margaret Bourke-White: Her Pictures Were Her Life, New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1999

→Brown Theodore M (ed.), Margaret Bourke-White, photojournalist, exh. cat., Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, (1972), Ithaca, Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University, 1972

Margaret Bourke-White: Moments in History, Martin-Gorpius-Bau, Berlin; Preus Meseum, Horten; Fotomuseum, The Hague; Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, 2013–2015

→Margaret Bourke-White, Andrew Dickson White Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, 1972

American photojournalist.

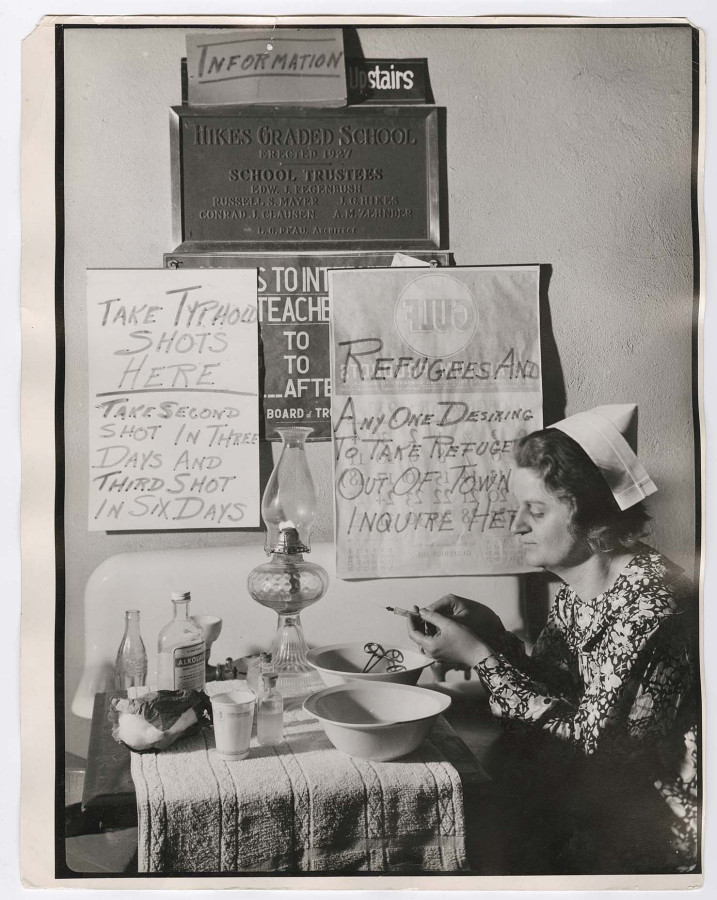

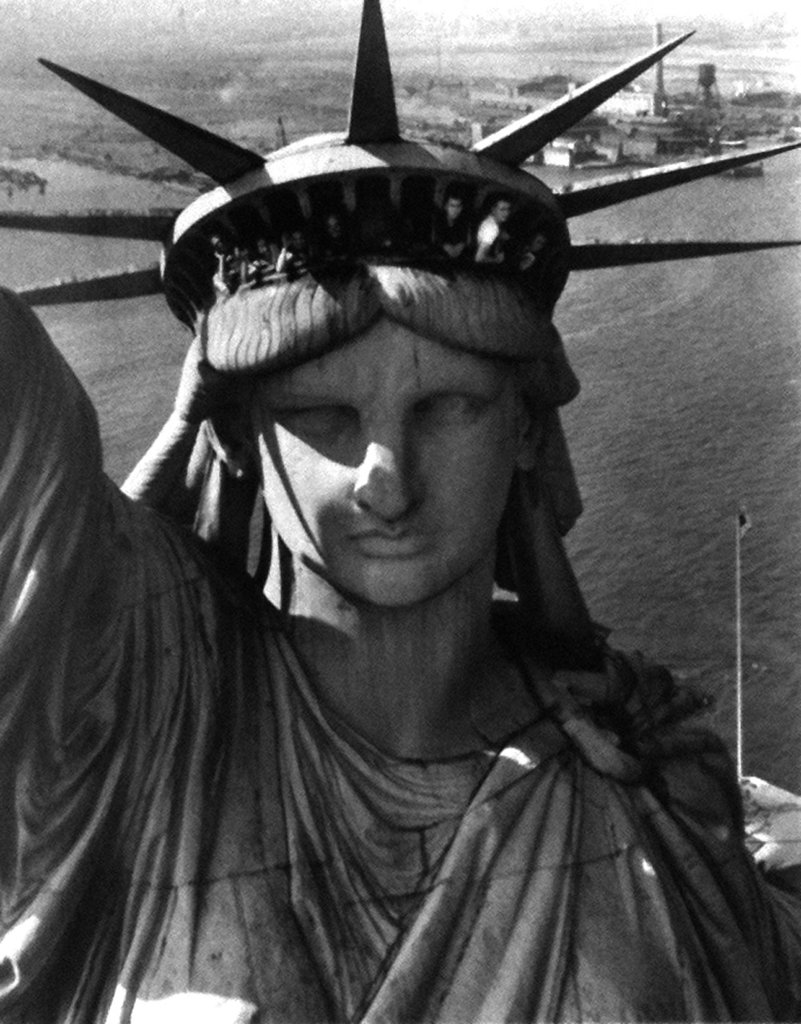

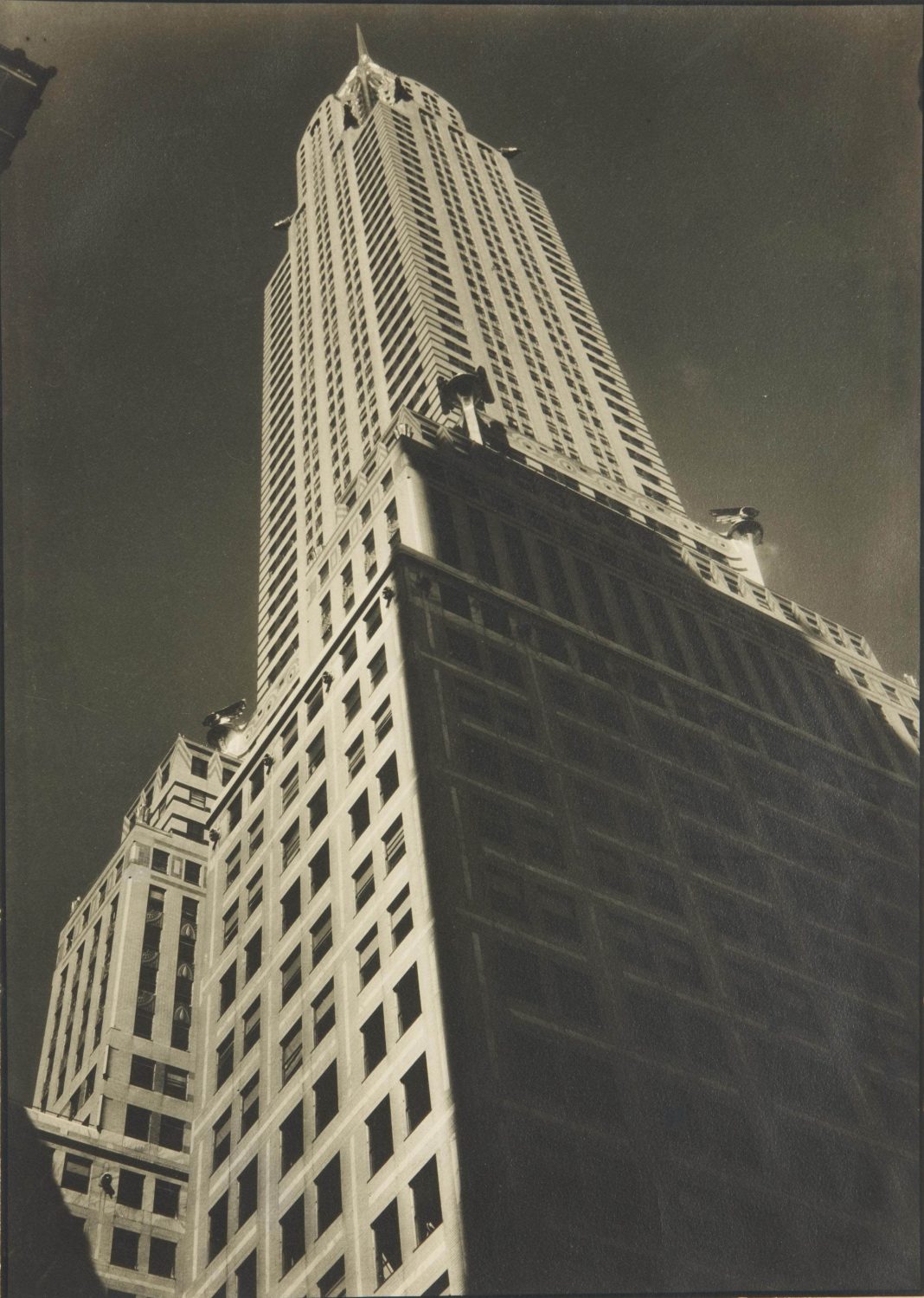

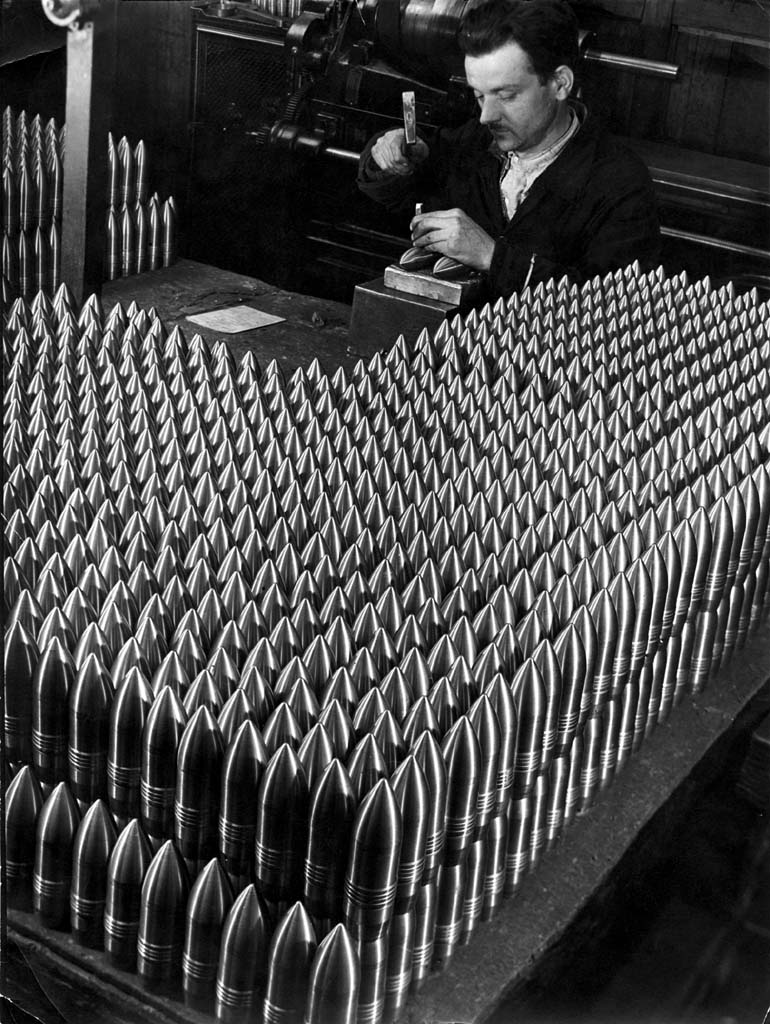

Margaret Bourke-White was a photojournalist who achieved fame in a predominantly male environment. Working at the heart of major historical events, she produced some of the most memorable images of the 20th century, some of which would later become iconic. The daughter of an engineer and amateur photographer, she perfected her craft, which she had acquired at Columbia, at the University of Michigan, and started selling a few pictorialist photographs in 1924. After her divorce two years later, she resumed her studies and graduated from Cornell University in 1927, then began a career as an architectural photographer in Cleveland. Her production at the time shared great likeness both with the American straight photography movement initiated by Paul Strand and with Laszlò Moholy-Nagy’s European modernist movement. Her “pure” photographs, taken at the Otis Steel Company between 1927 and 1928, glorify the machine and industrialisation in a context of national pride. Her commercial success enabled her to open a studio in Cleveland, the industrial photographs of which were honoured by the Museum of Art in 1927. Bourke-White began working as a photojournalist after she was hired by the American publisher Henry Luce to illustrate the first issue of Fortune magazine, published in 1930. Fortified by her recent success, she moved into the Chrysler Building in 1930. The same year, she spent five months in the USSR, where she photographed industrial plants and various five-year-plan building sites, while gaining knowledge of the photographic visual rhetoric of Soviet propaganda. Her Russian pictures were published in Fortune, then as a book, Eyes on Russia (1931).

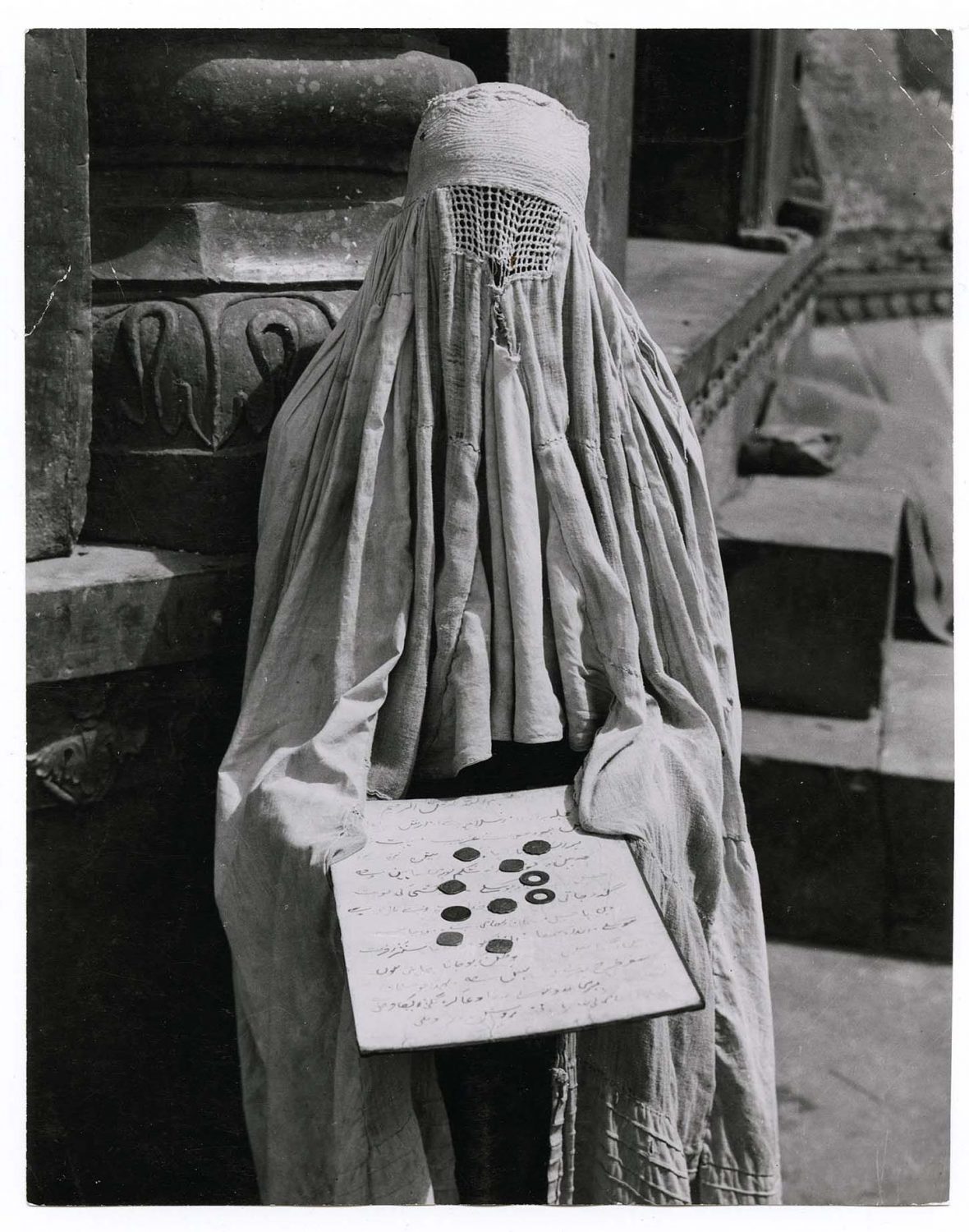

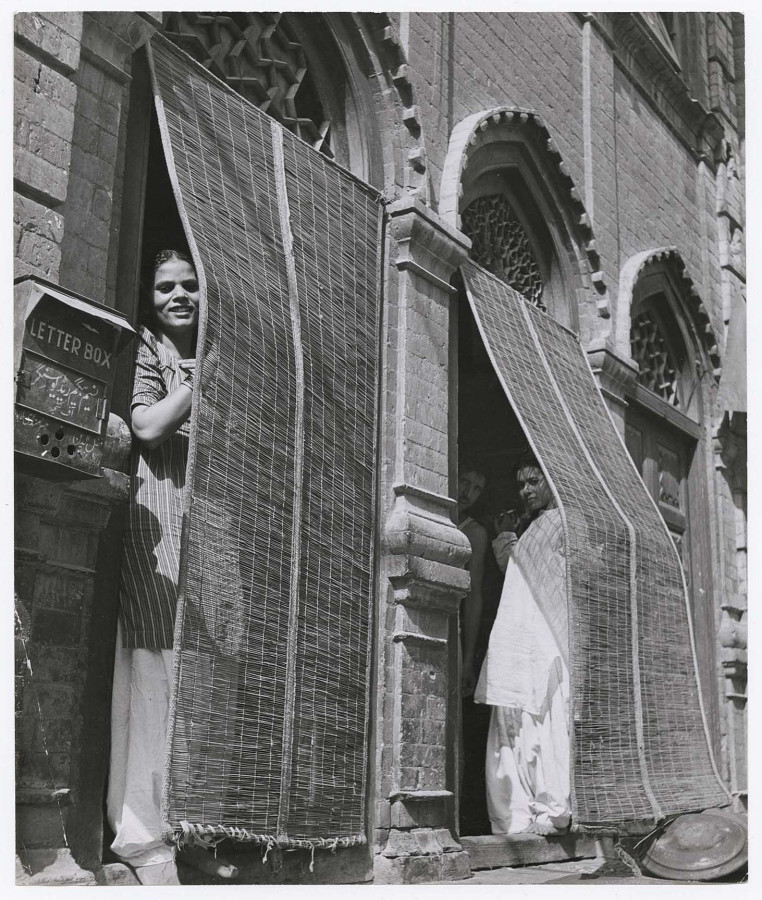

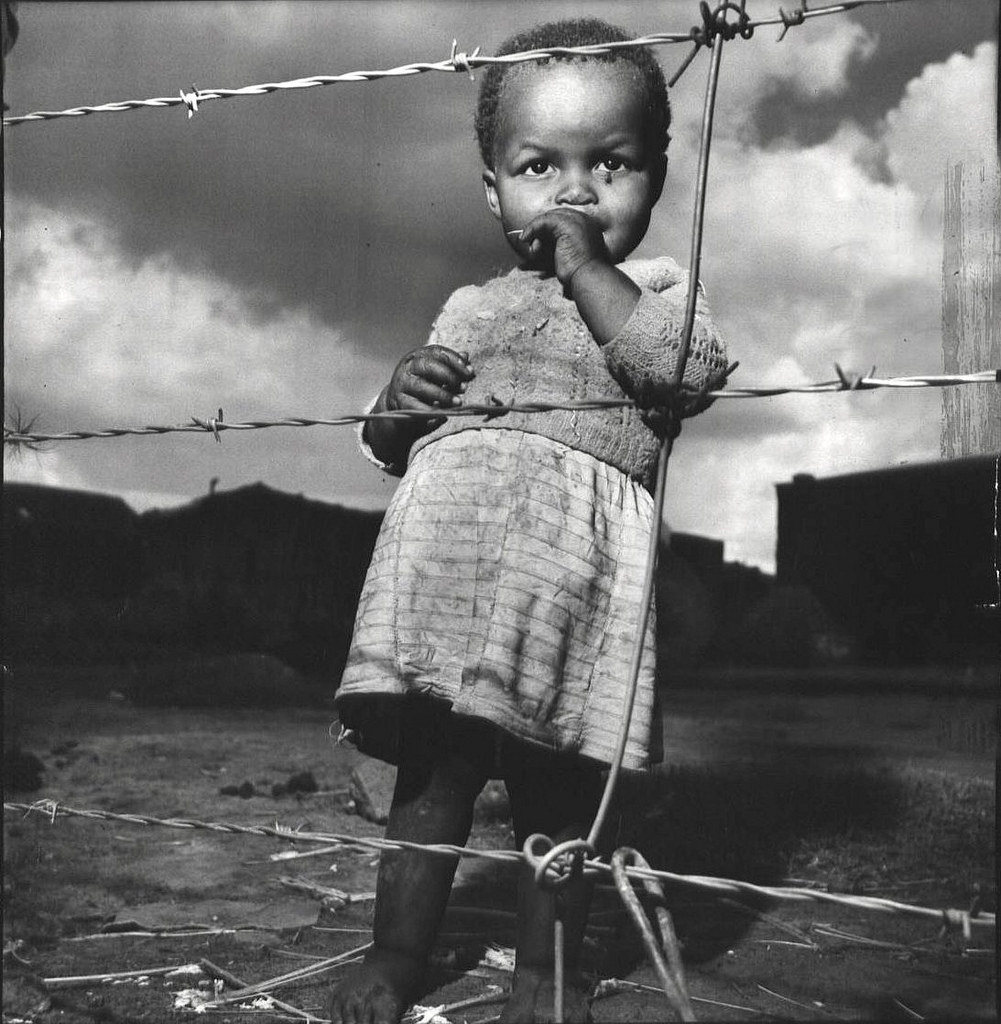

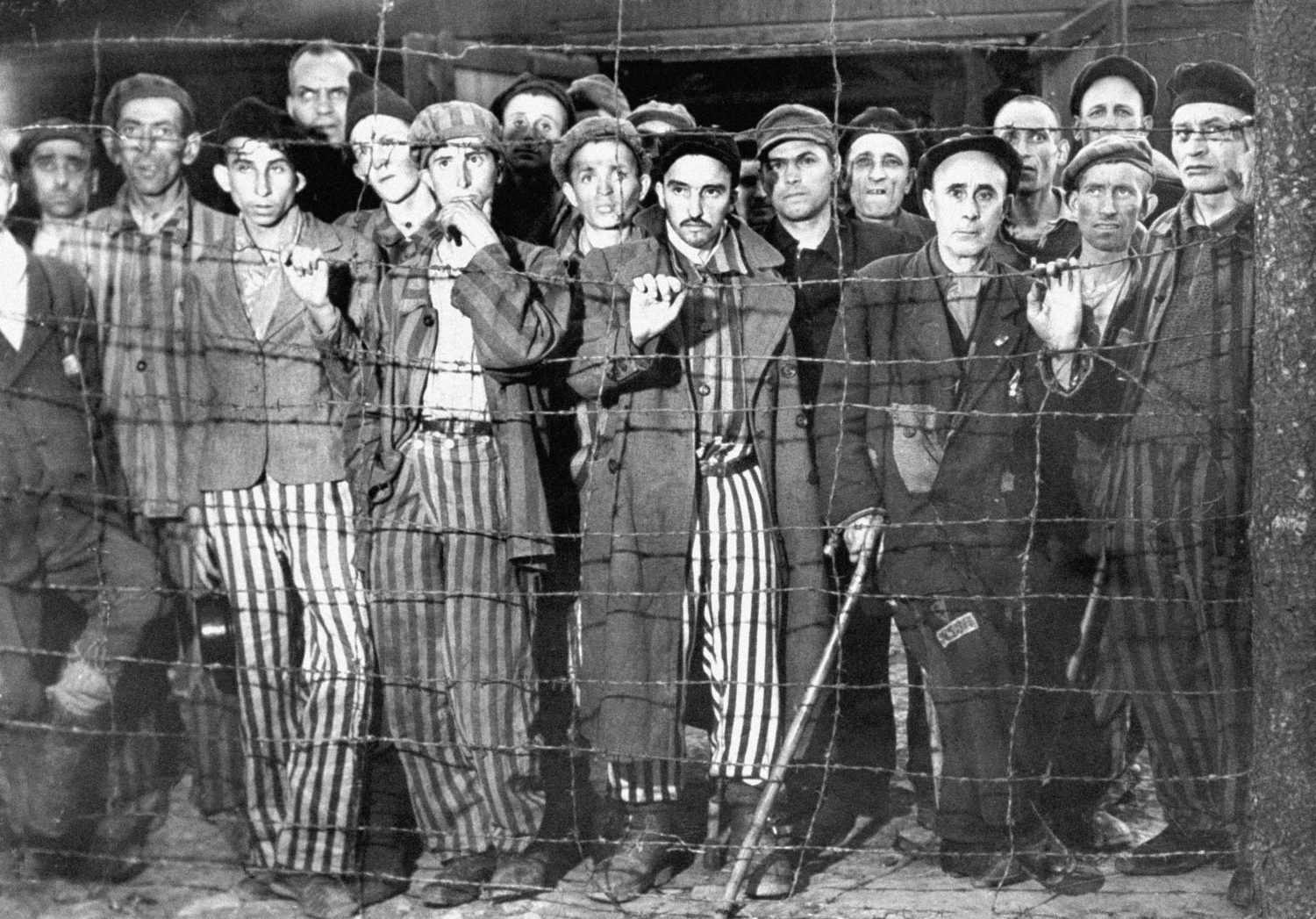

In the early 1930s, she collaborated with advertising agencies and numerous companies, and was commissioned the photographic mural of the Rockefeller Centre rotunda in New York in 1934. Around 1935–1936, she began to take an interest in individuals in their surroundings, whereas their presence remained rare or completely overpowered by machines in her earlier photographs. With the writer Erskine Caldwell, who famously chronicled misery in the South of United States, she considered a more social approach of her work. In 1936, in parallel with the Farm Security Administration project to help farmers suffering from the Great Depression, they travelled through the Southern States to document and denounce the injustices of tenant farming and the pauperisation of rural areas. Their collaboration led to the publication of one of the most successful books of the time, You Have Seen Their Faces (1937). Also in 1936, Life magazine launched its first issue with a cover photograph by Bourke-White, Fort Peck Dam, Montana. From 1939 onwards, Life regularly sent her on scoop hunts in Europe. In 1941, on the occasion of a second trip to the USSR with Caldwell, whom she married in 1939, she was the only foreign photographer present during the bombing of Moscow by the Germans. She published a fascinating account of the event in Shooting the Russian War (1940). As from 1942, she was the only female correspondent on the European front. While following General Patton through Germany in 1945, she photographed ruined cities and recently liberated concentration camps, including Buchenwald, after which she published Dear Fatherland, Rest Quietly. She continued travelling around the world for Life. She covered the 1947–1948 political events in India, made her now famous portraits of gold miners in South Africa between 1949 and 1950, and photographed the Korean War in 1951–1952. Her works were shown in 1955 at the famous Edward Steichen exhibition Family of Man, inaugurated at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Her autobiography, Portrait of Myself, was published in 1963 and became a bestseller in the US. Her archive collection is kept at Syracuse University, New York.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Margaret Bourke-White, Tribute Film, Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame

Margaret Bourke-White, Tribute Film, Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame