Focus

At the time of its invention, in 1839, photography was seen as a young medium with democratic goals, far from the gender discrimination that burdened the academic training of artists. From the outset women took up photography and made major contributions to its history, as well as its technical and aesthetic innovations. This is abundantly illustrated in the exhibition Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? 1839-1945, which was held at the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie in 2015-2016.

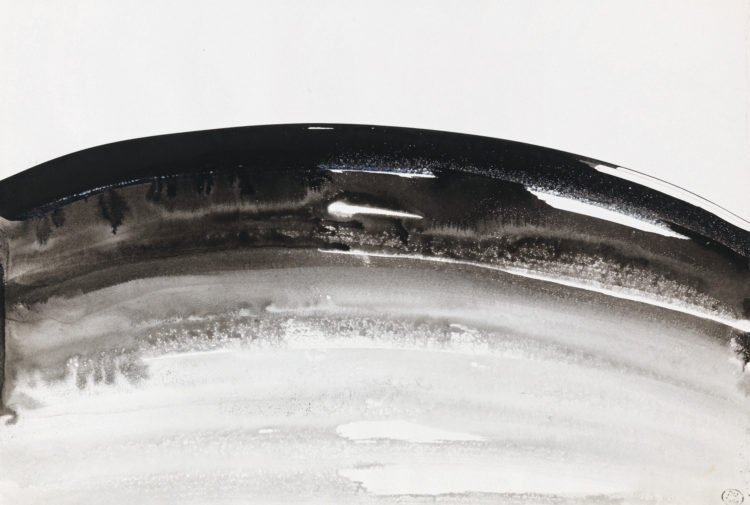

Amongst the female pioneers of photography, Anna Atkins (1799-1871) is recognized for her mastery of the cyanotype – a photographic process characterised by blue tints developed by John Herschel (1792-1871) in 1842 – that she used in a botanical publication as early as 1843, inaugurating the use of photography in book illustration. Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879) was an important representative of pictorialism. Although the movement was developed in amateur clubs, several women became involved as it aimed to raise the status of photography to that of art, including Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934) and Anne Brigman (1869-1950). Many of them made their mark in pictorialist circles before carrying out other experiments, following the upheavals of the world by founding an aesthetic adapted to modernity. For example Laure Albin Guillot (1879-1962), who explored microphotography amongst other things, opened the way to abstraction. Many of the photographers who undertook the formal research characteristic of the interwar period were linked to avant-garde movements, such as Florence Henri (1893-1982), whose vocabulary mixed the deconstruction of space and geometric forms echoing cubism and constructivism, and Dora Maar (1907-1997), whose photomontages reflect a dreamlike surrealist iconography. The book Métal (1928) by Germaine Krull (1897-1985) condensed her reflections on photography: the innovative angles and framing complemented modern architecture, making the artist a figure of the New Vision photographic movement.

Most of these artists attest to the increasing professionalisation of photographers in the early 20th century: abandoning the model of the first photographers from the bourgeoisie, female photographers became portraitists, architectural photographers, photojournalists, and worked in advertising. Imogen Cunningham (1883-1976) claimed this in her manifesto “Photography as a Profession for Women” (1913). She also worked for the emergence of straight photography in the United States. Documentary photography experienced a new expansion in the United States through the work of Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) and Tina Modotti (1896-1942), acquiring a social and political dimension. It stood out from the ethnographic photography in the work of Constance Stuart Larrabee (1914-2000), who was also known for being the first South African war correspondent. Embodied by Sabine Weiss (1924) in France, the humanist photography movement developed after the war, gaining a certain uncanniness in the scenes that Diane Arbus (1923-1971) captured on the streets of New York. Similarly Paz Errázuriz (born in 1944) turned her lens towards marginalised people, but her work was part of a genuine political resistance under the Chilean dictatorship.

Since the 1970s photographic practices have undergone an exponential development and diversification, from documentary to more hybrid forms, particularly with the emergence of so-called “fine art” photography. Joining the Düsseldorf School influenced by Hilla (1934-2015) and Bernd Becher (1931-2007), Candida Höfer (born in 1944) gave a breath of fresh air to documentary aesthetics with her large format frontal architectural photographs. Among the practices with which photography is associated, text has played a prominent role, as seen in the visual poems of Lenora de Barros (born in 1953) and the narrative works of Sophie Calle (born in 1953). Between reality and fiction the medium became a favoured tool for questioning representation and the visibility of identities. It is identity that is at the heart of the work of Nan Goldin (born in 1953), whose autobiographical scope and rawness have revolutionised the relationship to the intimate. Ishiuchi Miyako (born in 1947) explores the medium’s expressive capacities by first photographing places, revealing part of her personal history through images of Yokosuka, the city where she grew up, which is marked by an American presence. Some artists explore the theatrical potential of photography to probe the imaginary, such as Pushpamala N. (born in 1956), who quotes and diverts Indian cultural stereotypes and images drawn from Western art. Others approach the image from an openly militant perspective, such as Zanele Muholi (born in 1972), who works on the representation of black lesbian South Africans, among other things.

In addition to their diverse practices, some photographers also contributed to the history and theory of photography, such as Lucia Moholy (1894-1989), who wrote a cultural history of the medium in A Hundred Years of Photography, 1839-1939 (1939), as well as Gisèle Freund (1908-2000), whose Photography and Society (published in French in 1974 and English in 1980), based on her pioneering thesis on the sociology of photography, remains an important reference.

1899 — Germany | 1998 — United States

Ilse Bing

1869 — Hawaii | 1950 — United States

Anne Brigman

1883 — 1976 | United States

Imogen Cunningham

1879 — 1962 | France

Laure Albin Guillot

1893 — United States | 1982 — France

Florence Henri

1907 — 1997 | France

Dora Maar

1897 — Poland | 1985 — Germany

Germaine Krull

1895 — 1965 | United States

Dorothea Lange

1896 — Italy | 1942 — Mexico

Tina Modotti

1924 — Switzerland | 2021 — France

Sabine Weiss

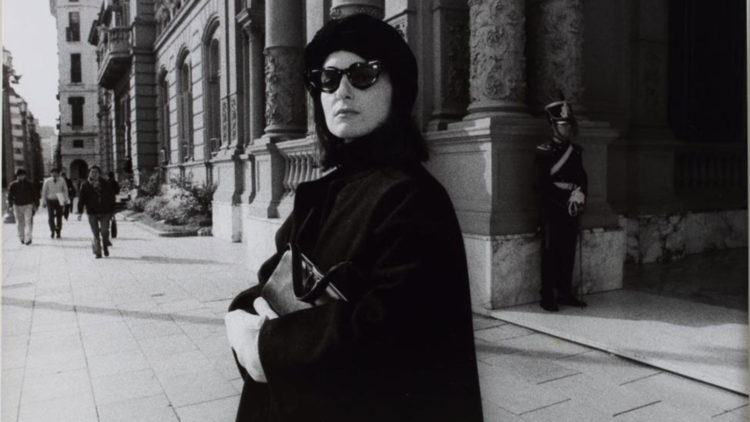

1944 | Chile

Paz Errázuriz

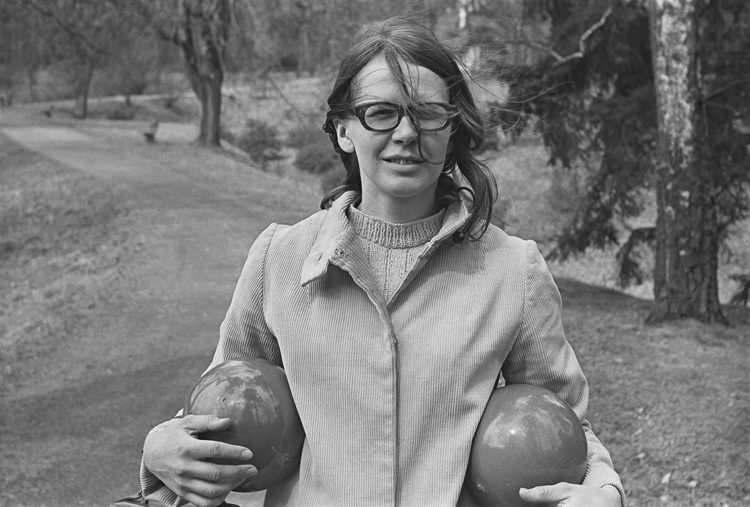

1934 — 2015 | Germany

Hilla Becher

1944 | Germany

Candida Höfer

1953 | Brazil

Lenora de Barros

1953 | United States

Nan Goldin

1956 | India

Pushpamala N.

1972 | South Africa

Zanele Muholi

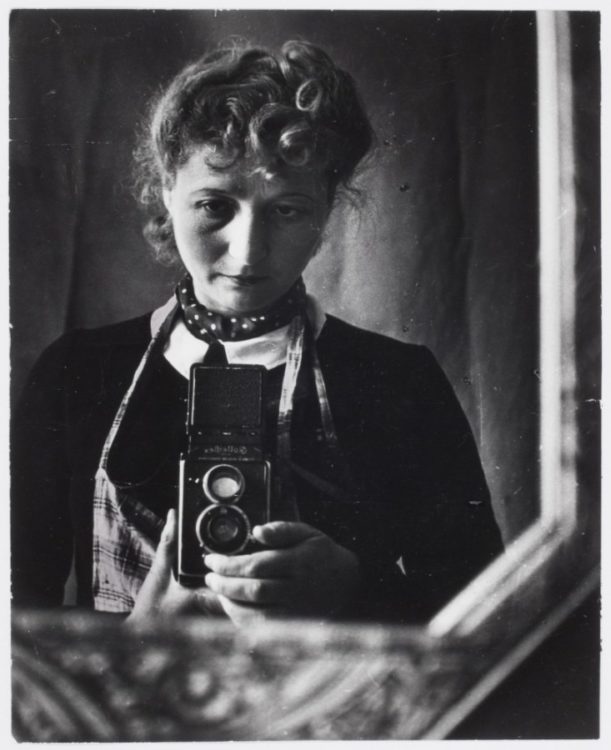

1894 — Czech republic | 1989 — Switzerland

Lucia Moholy

1908 — Germany | 2000 — France

Gisèle Freund

1864 — 1952 | United States

Frances Benjamin Johnston

1896 — Poland | 1990 — United States

Lotte Jacobi

1901 — Austria | 1983 — United States

Lisette Model

1913 — 2009 | United States

Helen Levitt

1949 | France

Sophie Ristelhueber

1951 — 1997 | Switzerland

Hannah Villiger

1962 | Cameroon

Angèle Etoundi Essamba

1957 | Spain

Ouka Leele

1852 — 1934 | United States

Gertrude Käsebier

1910 — Canada | 1997 — United States

Ida Lansky

1934 — 2024 | United States

Lorraine O’Grady

1956 | Morocco

Lalla Essaydi

1914 — United Kingdom | 2000 — United States

Constance Stuart Larrabee

1941 — 2010 | Germany

Sibylle Bergemann

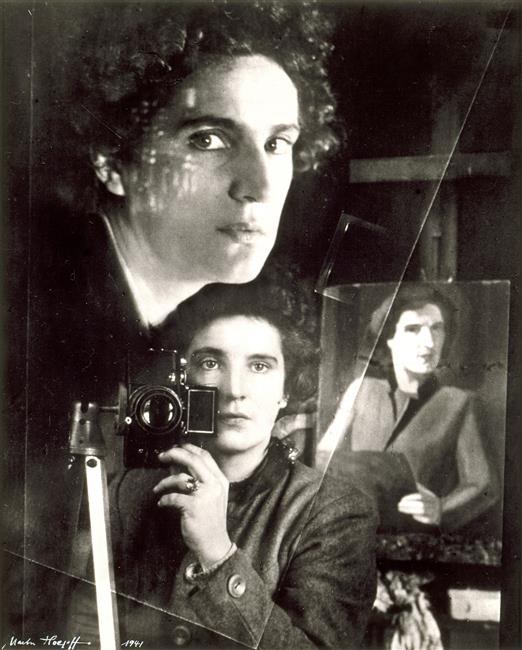

1912 — German Empire | 2000 — Germany

Marta Hoepffner

1799 — 1871 | United Kingdom

Anna Atkins

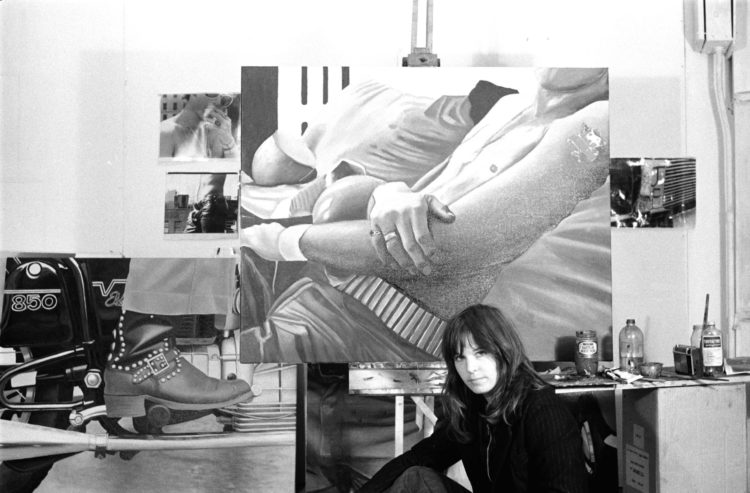

1948 — New Zealand | 2014 — England

Alexis Hunter

1959 — 2018 | United States

Laura Aguilar

1815 — India | 1879 — Sri Lanka

Julia Margaret Cameron

1901 — 1988 | United States

Carlotta Corpron

1940 — Mexico | 2022 — Portugal

Lourdes Grobet

1958 — Greenland | 2007 — Denmark

Pia Arke

1964 | Bulgaria

Liz Johnson Artur

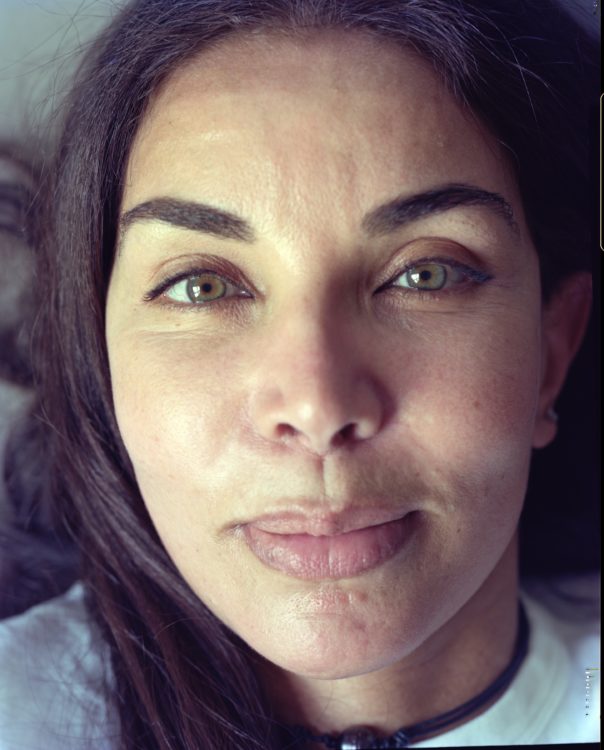

1964 | Lebanon

Rania Matar

1873 — France | 1961 — Switzerland

Céline Gracieuse Laguarde

1944 | Germany

Janina Green

1942 — Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic) | 2003 — Czech Republic

Zorka Ságlová

1967 | People’s Republic of China

Danwen Xing

1912 — 1999 | United States

Barbara Maples

1840 — 1893 | France

Marie (dite Maria) Chambefort

1953 | United States

Carrie Mae Weems

1953 | Guyana

Ingrid Pollard

1951 | United States

Donna Gottschalk

1926 — 2009 | United States

Vivian Maier

1963 | United States

Collier Schorr

1959 | Pays-Bas

Rineke Dijkstra

1935 — 2024 | Ghana

Felicia Abban

1960 | Germany

Vera Lutter

1948 | United States

Deborah Willis

1950 | United States

Ming Smith

1940 | Spain

Isabel Steva Hernández (dite Colita)

1961 | Australia

Lynette Wallworth

1962 | India

Sutapa Biswas

1951 — 1994 | Argentina

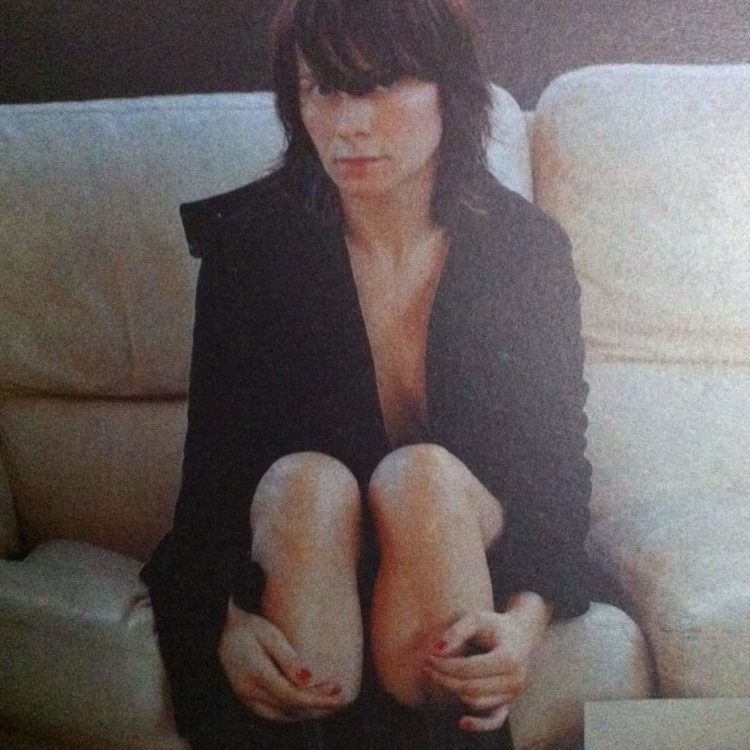

Liliana Maresca

1985 — United States | 1970 — Mexico

Rosa Rolanda (Rosemonde Cowan)

1882 — 1934 | United States

Doris Ulmann

1945 | United States

Barbara Kruger

1947 | United States

Louise Lawler

1964 | France

Valérie Belin

1961 | United States

Zoe Leonard

1947 | Poland

Yocheved Weinfeld

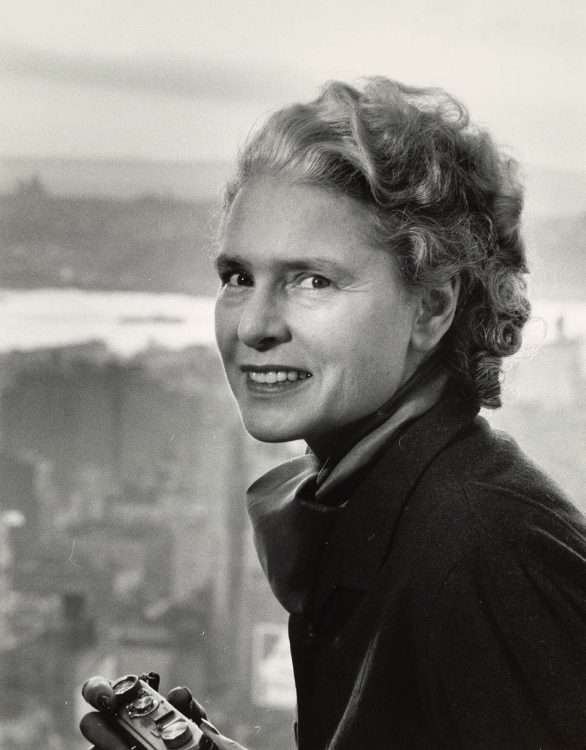

1904 — 1971 | United States

Margaret Bourke-White

1908 — Germany | 1994 — Israel

Liselotte Grschebina

1946 | Poland

Ewa Kuryluk

1955 | Canada

Geneviève Cadieux

1947 — 2013 | United States

Sarah Charlesworth

1907 — 2000 | Poland

Julia Pirotte

1968 | Albania

Ornela Vorpsi

1910 — 1943 | Hungary

Kata Sugár

1949 | France

Suzanne Lafont

1964 | France

Valérie Jouve

1970 | France

Rebecca Bournigault

1964 | United States

Sharon Lockhart

1962 | United Kingdom

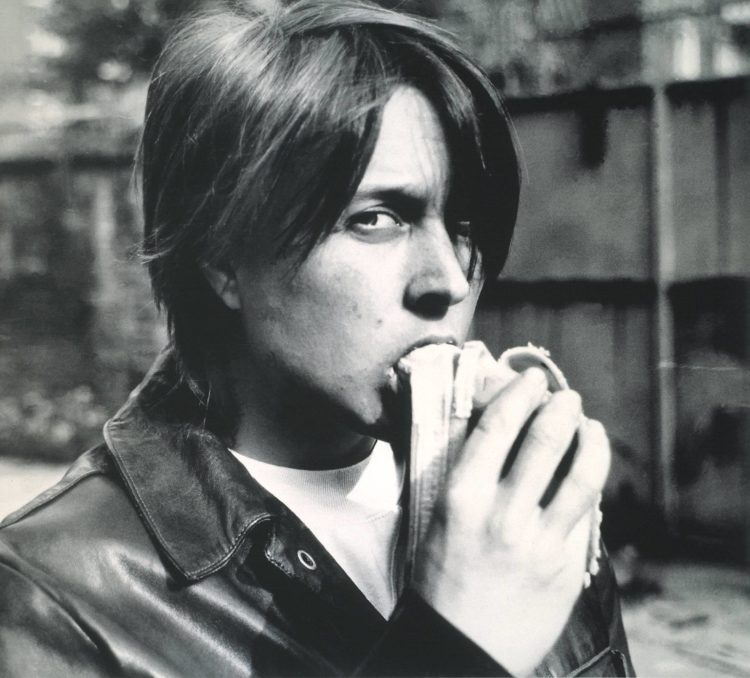

Sarah Lucas

1961 | South Africa

Jo Ractliffe

1958 | France

Anne Marie Jugnet

1951 | États-Unis

Cindy Sherman

1910 — Hungary | 2003 — Netherlands

Eva Besnyő

1970 | Tunisia

Mouna Karray

1958 — 1981 | United States

Francesca Woodman

1927 — 2005 | United States

Naomi Savage

1972 | United States

Maha Maamoun

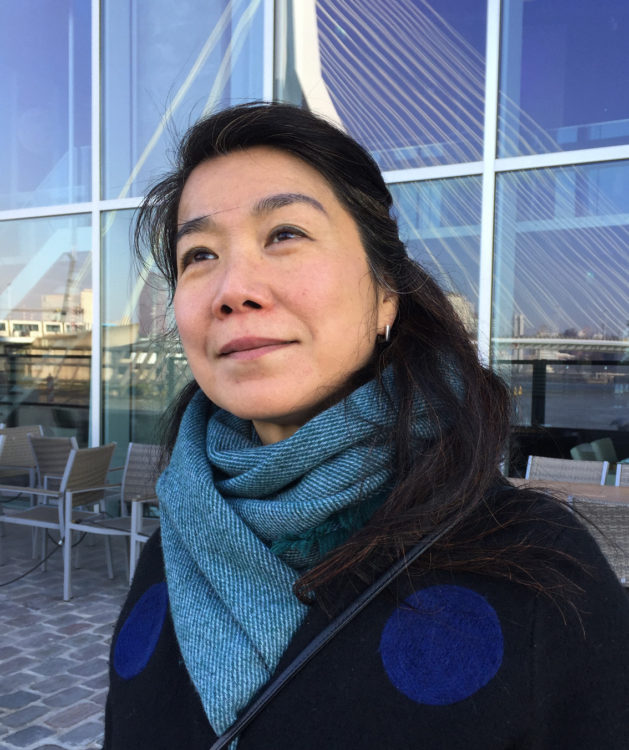

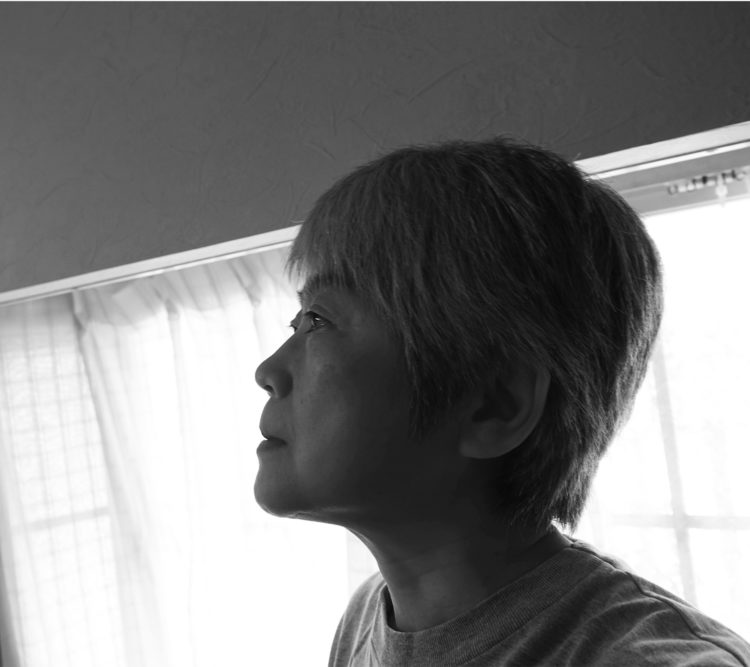

1947 | Japan

Miyako Ishiuchi

1873 — 1937 | Suriname

Augusta Curiel (Augustina Cornelia Paulina Curiel)

1959 | Australia

Polly Borland

1899 — 1995 | Japan

Eiko Yamazawa

1954 | United States

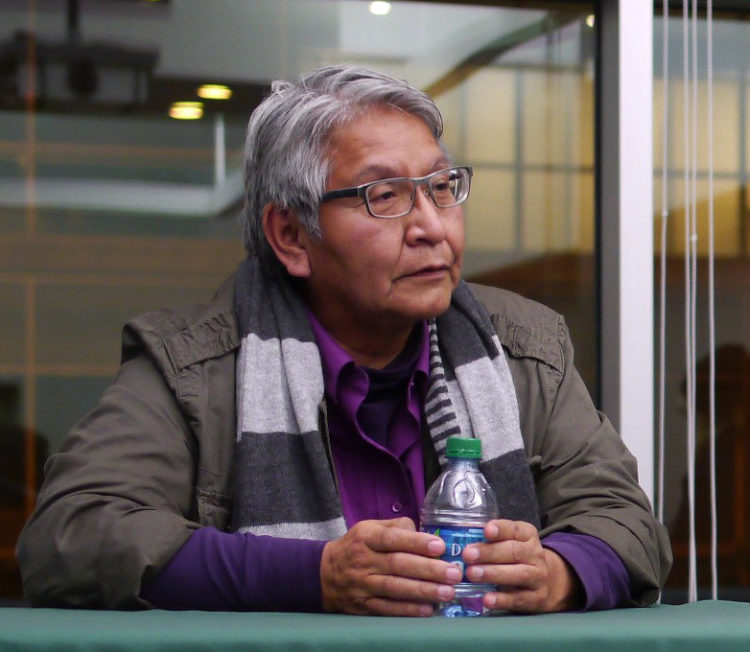

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie

1969 | Netherlands

Sara Blokland

1969 | Guyana

Moira Pernambuco

1919 — 2003 | Perú

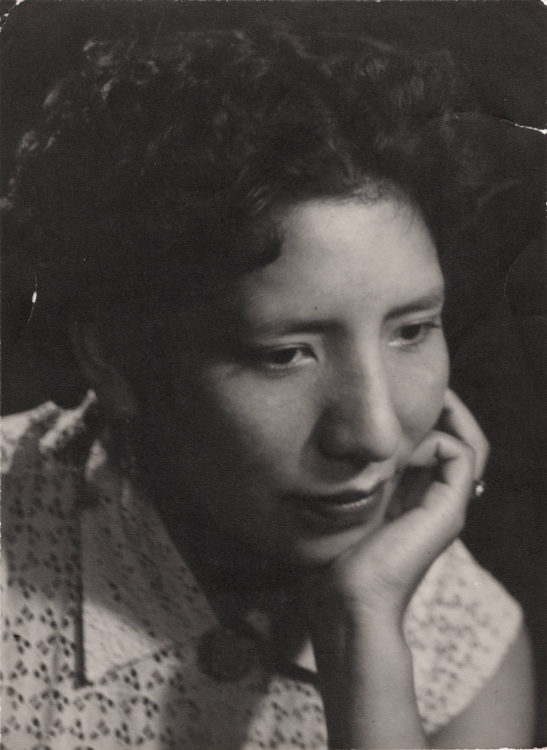

Julia Chambi López

1955 | Argentina

Adriana Lestido

1949 | Israel

Deganit Berest

1973 | United Kingdom

Clare Strand

1943 | Spain

Pilar Aymerich

1973 | France

Agnès Geoffray

1972 | Israel

Rona Yefman

1941 — 2016 | Malaysia

Nirmala Dutt Shanmughalingam

1938 — 1994 | Israel

Dalia Amotz

1962 | Japan

Yuki Onodera

1972 | Japan

Rinko Kawauchi

1973 | Iraq

Sama Alshaibi

1959 | Japan

Asako Narahashi

1974 | France

documentation céline duval (doc-cd)

1954 | Vietnam

Hanh Thi Pham

1957 | Tunisia

Marie-Antoinette Chiarenza

1906 — Russian Empire (now Lithuania) | 1998 — Lithuania

Veronika Šleivytė

1955 | Japan

Michiko Kon

1942 | Japan

Kunié Sugiura

1951 | United-States of America

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

1944 | France

Thérèse Ampe-Jonas

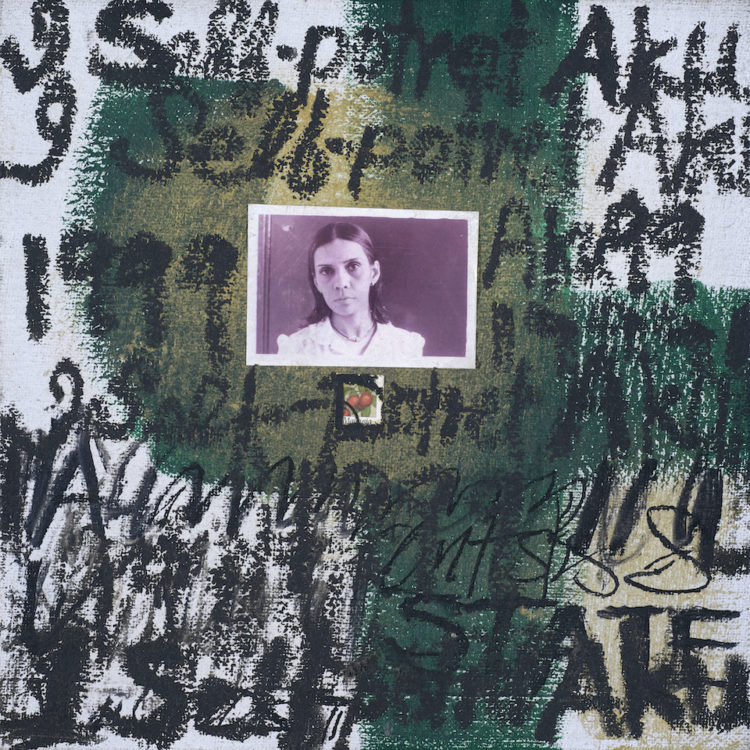

1939 — Indonesia | 2024 — Netherlands

Laura Samsom Rous

1971 | Japan

Rika Noguchi

1883 — 1962 | United States of America

Lora Webb Nichols

? | Japan

Hiroko Inoue

1973 | Japan

Yurie Nagashima

1868 — Great Britain | 1928 — United states