Kasahara, Hisako, The Women of the Ono House: Komachi and Ozū [Ono-ke no onnatachi: Komachi to Ozū], Tokyo, Kanrin Shobō, 2001

→Ogura, Kazuha, Ono no Ozū: The Momoyama Flower Revived from the Darkness of History [Ono no Ozū: Rekishi no yami kara yomigaeru momoyama no hana], Tokyo, Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 1994

→Fister, Patricia, Japanese Women Artists 1600–1900, Lawrence, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, 1988

The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting from the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 10 August 2024–3 August 2025

→Her Brush: Japanese Women Artists from the Fong-Johnstone Collection, Denver Art Museum, Denver, 13 November 2022–16 July 2023

→The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illuminated, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 5 March–16 June 2019

Japanese calligrapher, poet, and noblewoman.

The calligrapher, poet, musician and noblewoman Ono no Ozū (or Otsū; 1559/68–before 1650) remains an elusive figure in Japanese art history. One of the most prominent women calligraphers of the pre-modern period in Japan, today little is known for certain about her life, and scholars even disagree about the correct pronunciation of her name. She was a member of aristocratic circles in Kyoto, where she served as a lady-in-waiting, and she is thought to have received some form of patronage from all three of the so-called ‘Great Unifiers of Japan’, Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), at various points in her career. Her father was likely the feudal lord Ono Masahide (?–1562), an ally of Nobunaga, who allegedly placed her into the care of his attendants following the death of her father in battle. In Kyoto she became involved with the powerful Toyotomi family, either as a lady-in-waiting for one of Hideyoshi’s concubines or as an attendant for Hideyoshi himself.

After a short-lived marriage to a retainer of the Toyotomi family, Ono no Ozū began to support herself by tutoring aristocratic young women in a range of arts, such as calligraphy, music and poetry. Her prominence in this field is said to have attracted the attention of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who may have employed her as a teacher for his wife and daughter. Ono no Ozū’s later service to the Tokugawa family is said to have included a commissioned portrait of Ieyasu on his seventy-seventh birthday and accompanying daughters of the Tokugawa shoguns to their weddings. She likely served a similar role for imperial daughters as well.

Ono no Ozū lived and worked during the turbulent transitional years between the Momoyama (1574–1600) and Tokugawa (1603–1868) periods, and this is likely largely to blame for the sparse definitive information about her life that remains today. Women of her noble social status were amongst the most restricted during the Tokugawa period, typically confined to their homes or inner castle chambers. While these upper-class women did have more leisure time to pursue the arts, the level of widespread recognition that Ono no Ozū achieved amongst the ruling elite during her lifetime despite these constraints was extraordinary.

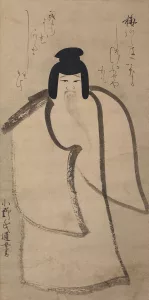

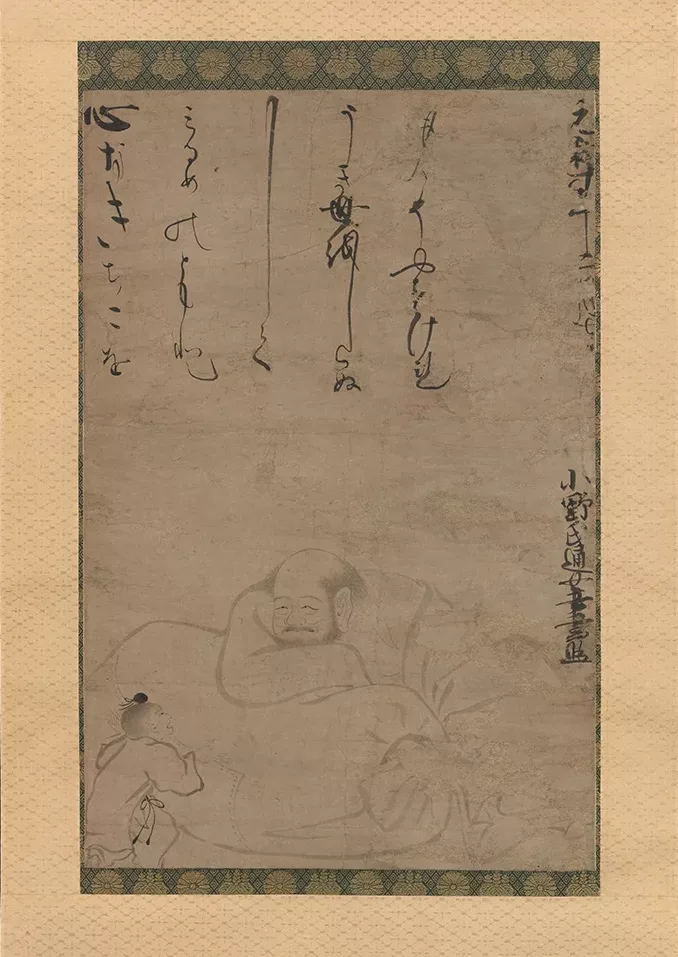

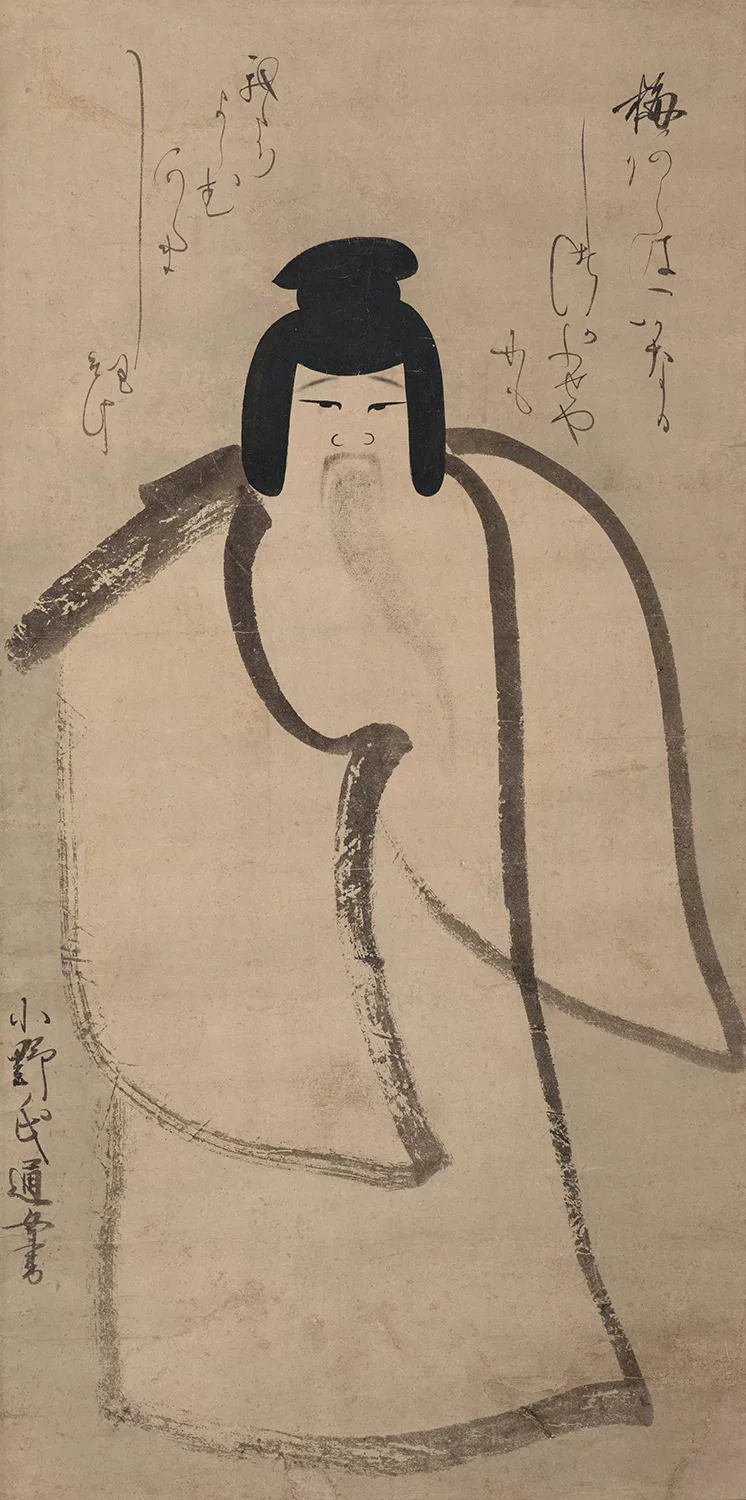

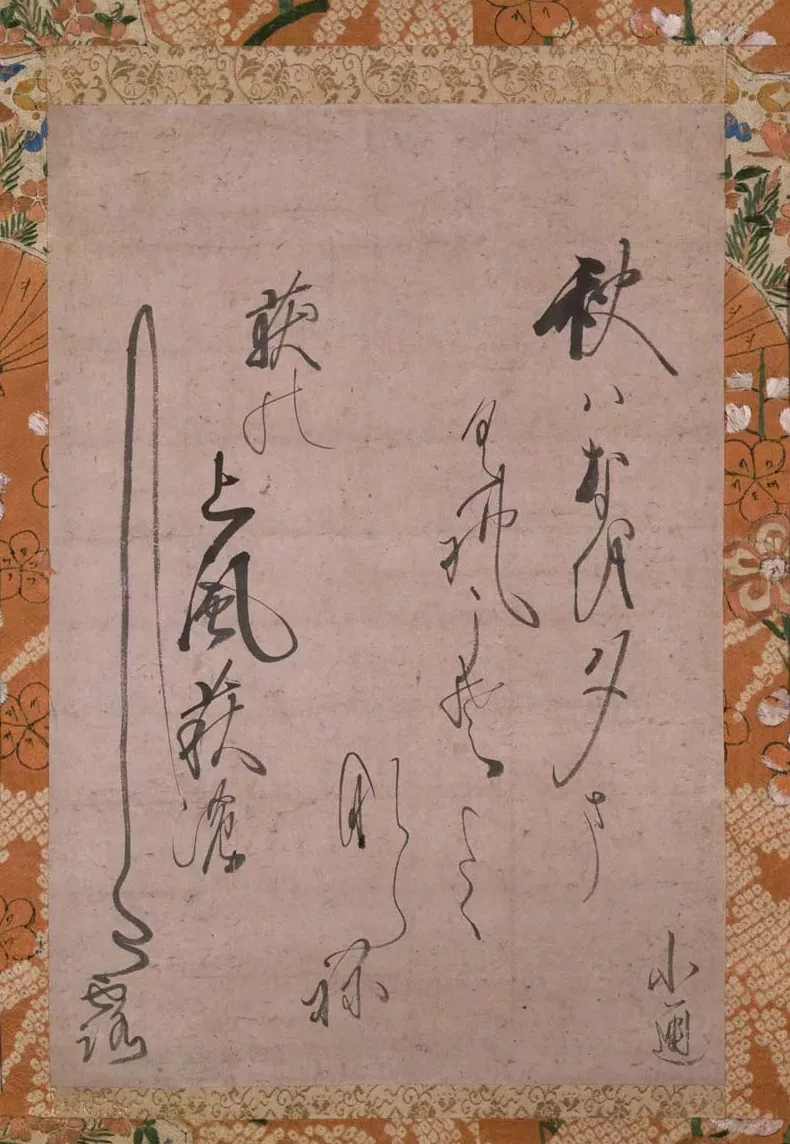

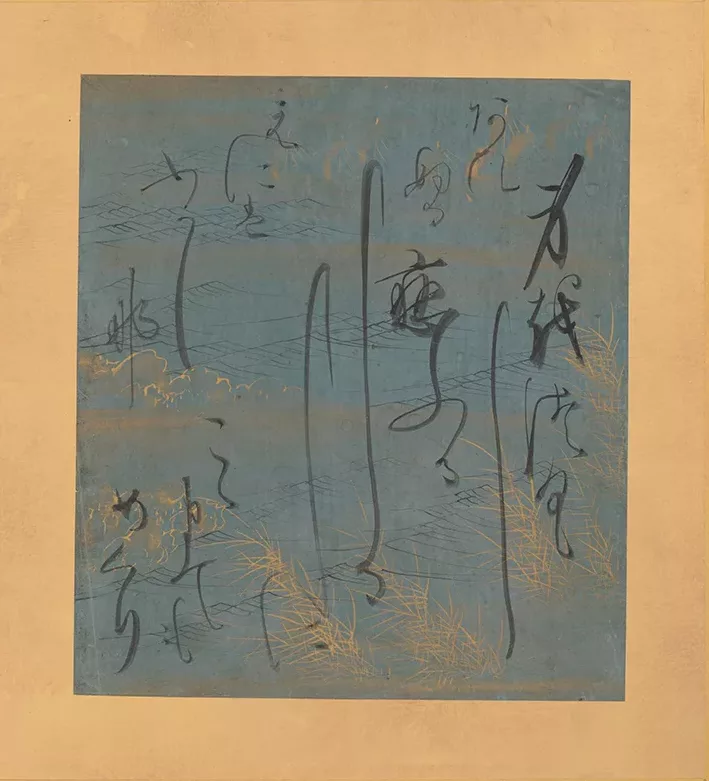

Ono no Ozū is best remembered today for her distinctive calligraphy, which is characterised by fluid linked strokes and brush flourishes, and reflects strong literary knowledge. Little is known about her artistic training, but her style continued to hold influence over upper-class women calligraphers through woodblock-printed books long after her death. She also seems to have been involved with the Tosa school of painters, and Calligraphic Excerpt from the Tale of Genji (early 1600s) represents the kinds of collaborations she created with its members. Although fewer examples survive, her paintings, such as Hotei with a Child (1624) and The Deified Sugiwara Michizane Crossing to China (early 1600s) are also highly regarded.

In collaboration with the Denver Art Museum as part of AMIS: AWARE Museum Initiative and Support

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025