Research

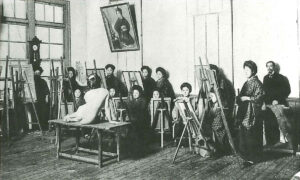

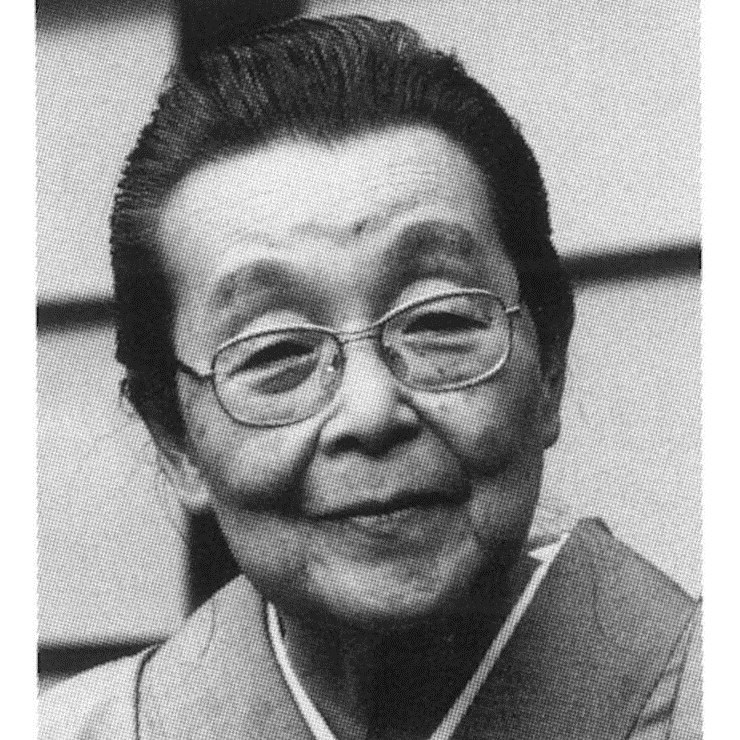

Antonio Fontanesi and his female students at the the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works, from left to right: Goro Takemoto, Masako Yamamuro, A. Fontanesi, bottom right: Yamashita Rin, bottom left: Itoko Kannaka

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the notion that modernisation = Westernisation was being promoted in Japan, Western concepts and techniques were rapidly adopted in the field of art, as they were everywhere else. During this process, terms such as bijutsu [art], kaiga [painting], chōkoku [sculpture] and kōgei [crafts] were established as translations of Western concepts. Corresponding words and techniques for these terms pre-existed in Japan, but they were reorganised in the early Meiji period to match Western concepts, and that reorganisation has persisted to this day.

In the Meiji 10s (1877-1886), the genre concepts of yōga [Western-style painting], which uses oil and watercolour techniques imported from the West, and Nihonga [Japanese-style painting], the traditional art of painting that originated in Japan, began to emerge. This relative concept of a “Japan” that existed in contraposition to “the West” clearly illustrates the conflict of Japanese art versus Western art.

The term Nihonga first appeared in “Bijutsu shinsetsu” [The Truth of Art], a lecture presented by Ernest Fenollosa,1 at the Ryūchi-kai2 in 1882. In the Meiji 20s (1887-1896) the institutionalisation of art proceeded in tandem with the establishment of a national polity, and the genres of Nihonga and yōga/seiyōga were created. In 1890 Masakazu Toyama3 presented a controversial lecture at the university, “Nihon kaiga no mirai” [The Future of Japanese Painting] in which he opined that Japanese painting had been hopelessly mired in the debate between the two schools. In 1896 a Western painting programme was established at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts,4 which was founded to preserve traditional Japanese painting. Eventually, in 1907, the Japanese government established the Bunten Exhibition,5 which included both Nihonga and seiyōga divisions, a move that led to the institutionalisation of both genres. Today, most Japanese art museums divide their collections into these two categories.

While the term yōga now carries a strong connotation of oil painting, that designation developed independently in Japan after the end of the Meiji period. It was originally used to indicate Western-style paintings more broadly, as the related term seiyōga suggests, and there may well have been a time when the creation of oil paintings by Japanese artists was viewed as something like a borrowing of technique. This entanglement continued for an extended period, from the Meiji to the Taishō (1912-1926) and finally to the Shōwa era (1926-1989). It was only in the aftermath of the Second World War that yōga came to be regarded as a unique genre within modern Japanese art.

It was not until the Bakumatsu period (1853-1867), when the shogunate began researching Western technologies, that the study of authentic oil painting techniques truly began. In 1857 a division for the study of paintings was founded at the Bansho Shirabesho [Institute for the Study of Barbarian Books], headed by the painter Tōgai Kawakami (1828-1881). In 1862 Yuichi Takahashi (1828–1894) began studying at the institution and progressing in his painting. Together with Yoshimatsu Goseda (1855-1915), Y. Takahashi later studied oil painting under the artist Charles Wirgman.6 Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Shinkurō Kunisawa (1848-1877), Kiyoo Kawamura (1852-1934), and, somewhat later, Hōsui Yamamoto (1850-1906) all travelled to Europe to learn oil painting.

In 1876 Japan’s first institution for art education, the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works (Kōbu Bijutsu Gakkō), was founded. It featured two departments for painting and sculpture, and Italian painter Antonio Fontanesi (1818–1882) and Italian sculptor Vincenzo Ragusa (1841–1927) were invited to take up teaching posts. Shortly after its establishment, the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works began admitting female students, and – along with Y. Hōsui, Y. Goseda, Chū Asai (1856-1907), Shōtarō Koyama (1857–1916), and Hisashi Matsuoka (1862-1944) – Rin Yamashita (1857–1939), Masako Yamamuro (1858-1936), Sono Akio (1863-1929), Chō Sugawa (dates unknown), Hinako Ōshima (dates unknown), Hanako Kawaji (dates unknown), and Itoko Jinnaka (1860-1943) all studied under A. Fontanesi. Scholars have speculated that women were admitted to the programme early on because the Meiji government, having seen the high degree of education possessed by Western women, had resolved to turn their focus toward providing women with an education equivalent to men. This was not a reflection of the modern ideal of educational equality, but rather an undertaking motivated by the idea that the women who were responsible for raising men should have an education. In the early Meiji period, public and private girls’ schools were founded in rapid succession, beginning with the government-run Tokyo Girls’ School, which opened in 1872. Under the auspices of these favourable conditions, the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works welcomed female students with open arms.

Although female students were placed in separate classrooms from their male counterparts, they seem to have followed the same curriculum with A. Fontenesi. However, following his resignation in 1878, the female students dropped out one after another due to marriage, illness or dissatisfaction with his successor. As a result, not a single woman graduated. The circumstances of these women’s lives after they left school reveal the difficulties women of this era faced as artists. H. Ōshima and H. Kawaji, who came from wealthy families, never intended to earn a livelihood from painting and had learned oil painting as the latest refinement for upper-class women. M. Yamamuro, who had gained missionary support by joining the Eastern Orthodox Church, abandoned her studies in Russia due to her marriage and pregnancy. She later opened a print shop with her husband, Takeshirō Okamura, and worked as a lithographer. S. Akio married the photographer Matsuchi Nakajima (1850-1938) and went on to assist her husband in manufacturing magic lanterns while also working as a drafter and colourist.

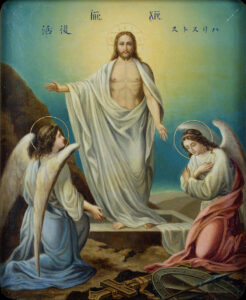

Rin Yamashita, Harisutosu fukkatsu [The Resurrection], 1891, oil on cloth, 32 × 26.4 cm, The State Hermitage Museum

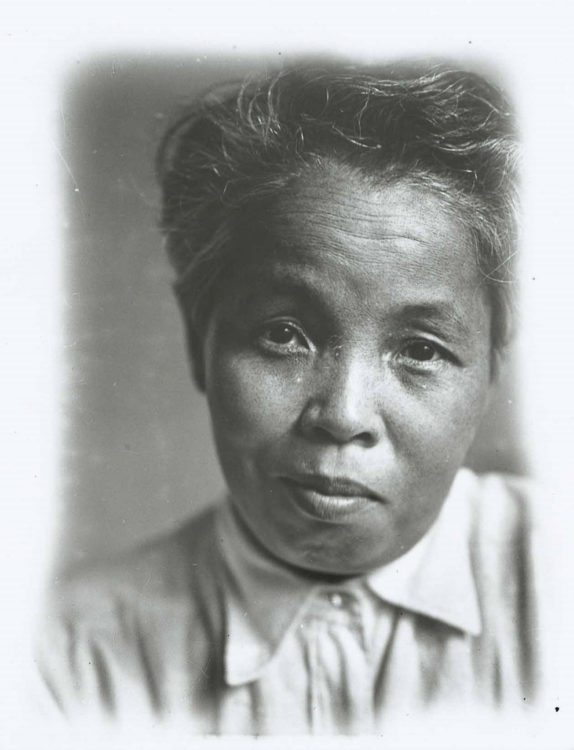

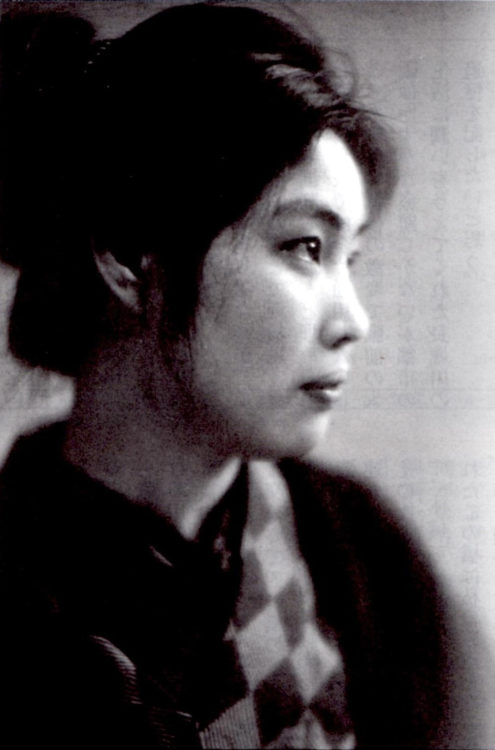

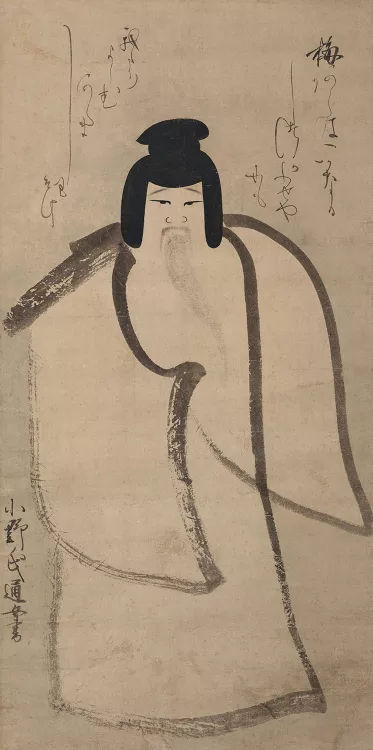

Of the women who studied at the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works, Y. Rin and I. Jinnaka devoted themselves to painting rather than becoming housewives. Y. Rin, who also joined the Eastern Orthodox Church, took over M. Yamamuro’s scholarship in Russia and lived in a convent in Saint Petersburg for two years, learning the craft of icon-making. Following her return to Japan, she established a studio within the women’s seminary of the Japanese Eastern Orthodox Church in Kanda, Tokyo, cutting herself off from the outside world to immerse herself in her work and leaving behind more than three hundred icons. I. Jinnaka, on the other hand, apprenticed with K. Shōtarō after leaving school and joined the Jūichi-kai. 7 A trailblazing woman yōga artist, I. Jinnaka’s work was selected for inclusion at the National Industrial Exhibition and Bunten Exhibition. Incidentally, the Meiji Bijutsu-kai, which served as a major venue for yōga artists to exhibit their work before the advent of government-sponsored exhibitions, seems to have exhibited work by quite a few women artists, though the particulars of this are unknown.

Tama Ragusa, Haru [Spring], 1912, oil on canvas, 89.5 × 71.2 cm, Tokyo University of the Arts

Yuka Watanabe, Yōji-zu [Child], 1893, oil on canvas, 57.8 × 84 cm, Yokohama Museum of Art

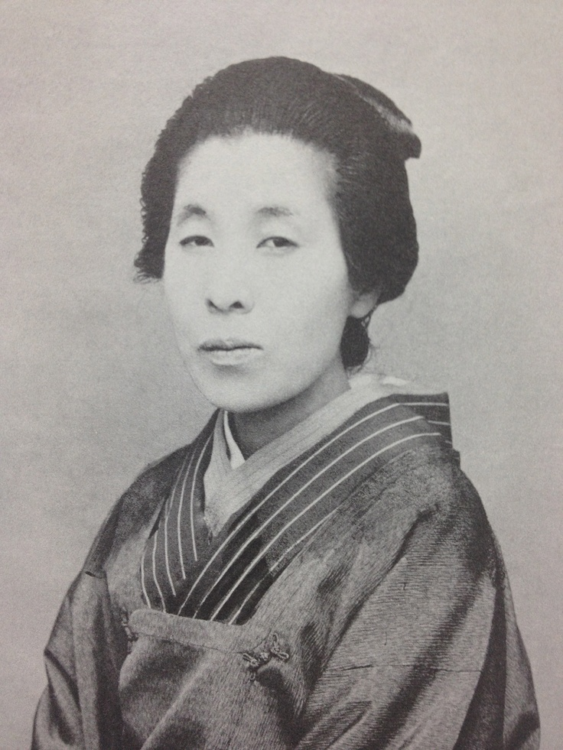

In addition, we cannot forget about those women who, though they did not study at the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works, were of the same generation and made their living as yōga artists: Yūkō Watanabe (1856-1942) and Tama Kiyohara (1861-1939), who later married V. Ragusa and went by the name Ragusa Tama.

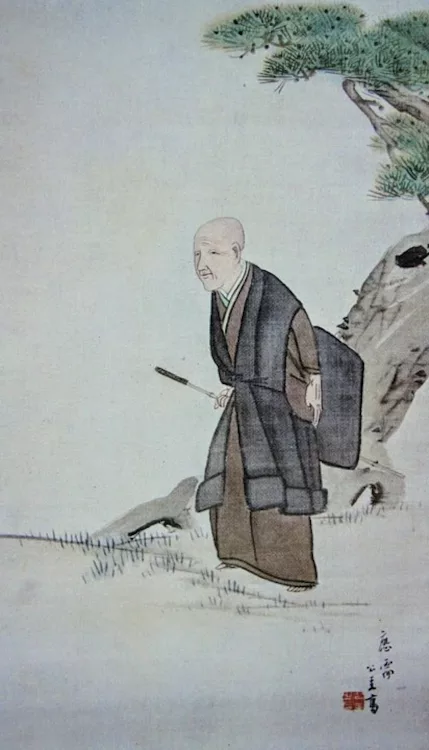

Y. Watanabe’s father, Hōryū Goseda (1827-1892) and older brother, Y. Goseda, were both yōga artists and she learned the craft from the latter in their father’s studio. Although she aspired to forgo marriage and concentrate on yōga painting, she ultimately married an artist of the same school at her father’s behest. However, even after marriage, she actively continued her artistic career, exhibiting at the National Industrial Exhibition and the Women’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, learning printmaking, and publishing collections of Japanese genre pictures aimed at a Western audience. She was also involved in the training of future generations of artists, working as a teacher at the Kazoku Jogakkō [Peeresses’ School] and the Joshi Kōtō Shihan Gakkō [Women’s Higher Normal School]. T. Kiyohara , by contrast, met V. Ragusa in 1877 while working as a sculptor’s model and began taking painting instruction. The two married in 1880, and she enrolled in an art course at the University of Palermo two years later. After studying drawing and oil painting, she eventually began showing her work in exhibitions in Italy and other European countries. Upon her return to Japan after V. Ragusa’s death, she devoted herself to painting, taking several sketching trips across Japan.

Motoko Morita, Omoi [Thinking], 1947, oil on canvas, 90.8 × 80 cm, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, © Photo: MOMAT / DNPartcom

Satoe Arima, Akai ōgi [Red Fan], 1925, oil on canvas, 73 × 53 cm, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, © MOMAT / DNPartcom

The Art School of the Ministry of Public Works closed in 1883 and the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, founded in 1887, did not admit women. It was not until 1945, that the school became co-educational. The Kyoto Shiritsu Senmon Gakkō [Kyoto Municipal Specialized School for Painting],8 located in Kansai, also did not admit women until 1945. In the first half of the twentieth century, women who wished to become artists had to enrol at the Shiritsu Joshi Bijutsu Gakkou [Private Women’s School of Fine Arts],9 which opened in 1901. While the “good wife-wise mother doctrine” was the hallmark of women’s middle and higher education, the goal of Joshibi was to provide women with professional and specialised education. Tamako Yokoi (1855-1903), one of Joshibi’s founders, had learned watercolour and oil painting from C. Asai and Kinkichirō Honda (1851-1921) while teaching at various girls’ schools following the death of her husband when she was just 20 years old. She later joined the Meiji Bijutsu-kai and Hakuba-kai (White Horse Society), an organisation for yōga artists. During time teaching, she became keenly aware of the need to train female educators in order to improve women’s status and independence. Her own abiding interest in art was likely a strong factor in the furtherance of her plans. Joshibi, which was opened with the support of Bunzō Fujita (1861-1934) – a professor of sculpture at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts – and others, was immediately faced with a lack of funds and in danger of closing down. In an era when art-only schools were unique, people cast an indifferent eye on a school that declared itself to be just for women. Joshibi was saved by Shizu Satō.10 She, too, aspired to improve the status of women, and when T. Yokoi asked for support, she set herself to the task of rebuilding, laying the foundation for the institution that exists today.

Male art professors from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts were invited to serve as instructors, eventually paving the way for graduates of the school to become full-time professors. In class, figure drawing was done from both plaster figures and live models, enabling students to learn the fundamentals of drawing the human form. Fumiko Kametaka (1886-1977), an early graduate and active painter, was the first woman yōga artist to receive a commendation at the Bunten Exhibition, a venue she exhibited at many times. F. Kametaka also participated in the founding of the Shuyoukai Art Association, the first public art organisation for women artists. Furthermore, Motoko Morita (1903-1969), Kōko Fukazawa (1903-1993), Setsuko Migishi (1905-1989), Hitoyo Kai (1902-1963) and many other women artists who were active participants in Japanese art circles, such as those surrounding the Kanten (official exhibition) and Nika exhibitions, graduated under the tutelage of the yōga artist Okada Saburōsuke (1869-1939), who took up the post of instructor in 1916. S. Okada also ran a private painting school, the Joshi Yōga Kenkyūjo (Women’s Yōga Research Institute), at which Satoe Arima (1893-1978), as well as M. Morita, S. Migishi, and Yukiko (Yuki) Katsura (1913-1991) also studied for a time. Finally, it would be remiss not to mention Toshiko Akamatsu (Toshi Maruki, 1912-2000) who was one of the women artists to study at Joshibi prior to the war.

Looking at the names of artists who studied at the school, we can see that many of them transcended the category of woman artist and indeed led the field of yōga painting through the Taishō and Shōwa periods. Nevertheless, compared with male artists of the period, research into and evaluation of these women and their work remains woefully insufficient—an issue that will need to be addressed in the future.

Ernest Fenollosa (1853–1908) came to Japan to serve as an adviser to the Japanese government and developed an interest in Japanese art.

2

The forerunner of the Japan Art Association.

3

M. Toyama (1848-1900) sociologist and Imperial University professor.

4

Now the Tokyo University of the Arts, which had been founded in 1887under the guidance of Okakura Kakuzō (1862-1913) and E. Fenollosa.

5

The first iteration of the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition

6

This research group devoted to yōga was founded by a circle of artists including K. Shōtarō and A. Chū following the completion of their studies at the Art School of the Ministry of Public Works. It later became the Meiji Bijutsu-kai, or Meiji Fine Arts Association.

7

The school was founded in and is now a part of the Kyoto City University of Arts.

8

Shortened as “Joshibi”, it is now the Joshibi University of Art and Design.

9

Shizu Satō (1851–1919), was the wife of the director of Juntendo University Susumu Satō (1845-1921).

10

Shizu Satō (1851–1919), was the wife of the director of Juntendo University Susumu Satō (1845-1921).

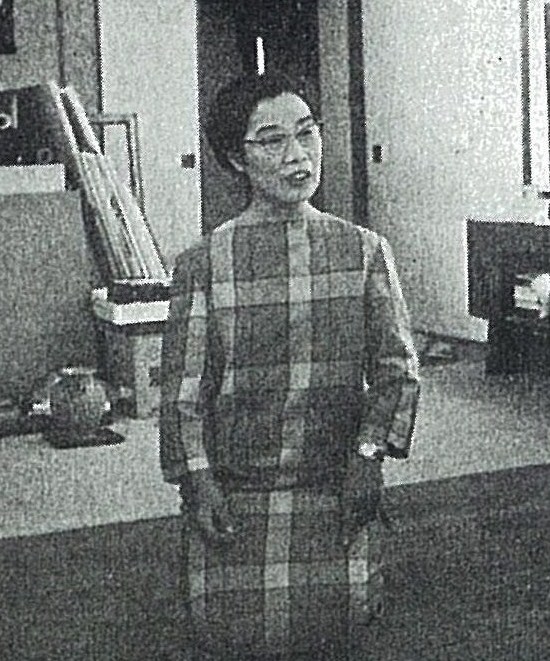

Yukiko Yokoyama is a curator at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. She completed doctoral coursework in Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies at The University of Tokyo, followed by research in the history of art and representation at Université Paris Nanterre la Défense. Her curatorial positions include assistant curator at the Setagaya Art Museum (2009-2011); associate curator at The National Art Center, Tokyo (2013-2018); curator at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa (2018-2022). She specializes in Japanese and French modern art, and in recent years has been researching women painters of the Japanese modern era.

An article produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme

Yukiko Yokoyama, "A History of Western-Style Yōga Painting in Japan and Women Yōga Artists from the Meiji Period to the Pre-War Era." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/le-style-occidental-au-japon-yoga-et-les-peintres-japonaises-entre-louverture-du-japon-en-1868-et-la-deuxieme-guerre-mondiale/. Accessed 14 July 2025