Patricia Johanson

Sue Spaid, Built, Proposed, Collected & Published, A Field Guide to Patricia Johanson’s Works, Baltimore, Contemporary Museum, 2012

→Xin Wu, Patricia Johanson’s House & Garden Commission : Reconstruction of Modernity, v.I et v.II, Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Contemporary Landscape Design Series, 2007

→Caffyn Kelley, Art and Survival. Patricia Johanson’s Environmental Projects, Salt Spring Island, Islands Institute, 2006

Groundswell: Women of Land Art, Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, September 23, 2023 – January 7, 2024

→Patricia Johanson: House & Garden, Usdan Gallery, Bennington College (VT), February 25 – May 9, 2020

→Patricia Johanson: The World as a Work of Art, Museum Het Domein, Sittard (NL), September 29, 2013 – January 26, 2014

US eco-artist.

A pioneer in landscape restoration design, Patricia Johanson forged an approach bringing together ecological imperatives and biomimicry, well before its 1997 theorisation by science writer Janine Benyus, while also rebuilding social connections in deteriorated urban and suburban settings. She earned a bachelor’s degree in art at Bennington College in Vermont in 1962.

She was soon noticed by artist Tony Smith (1912–1980) and by art historian Eugene Goossen, who would become her husband in 1974. In that same period, she came into contact with other influential artists including Barnett Newman (1905–1970), Franz Kline (1910–1962), Philip Guston (1913–1980), Joseph Cornell (1903–1972), for whom she would later work as an assistant, and Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), with whom she formed a friendship. In 1964, while completing her master’s degree in art history at Hunter College in New York, she assisted Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) with the cataloguing of her work and archives. O’Keeffe ultimately assumed the role of mentor to the budding artist.

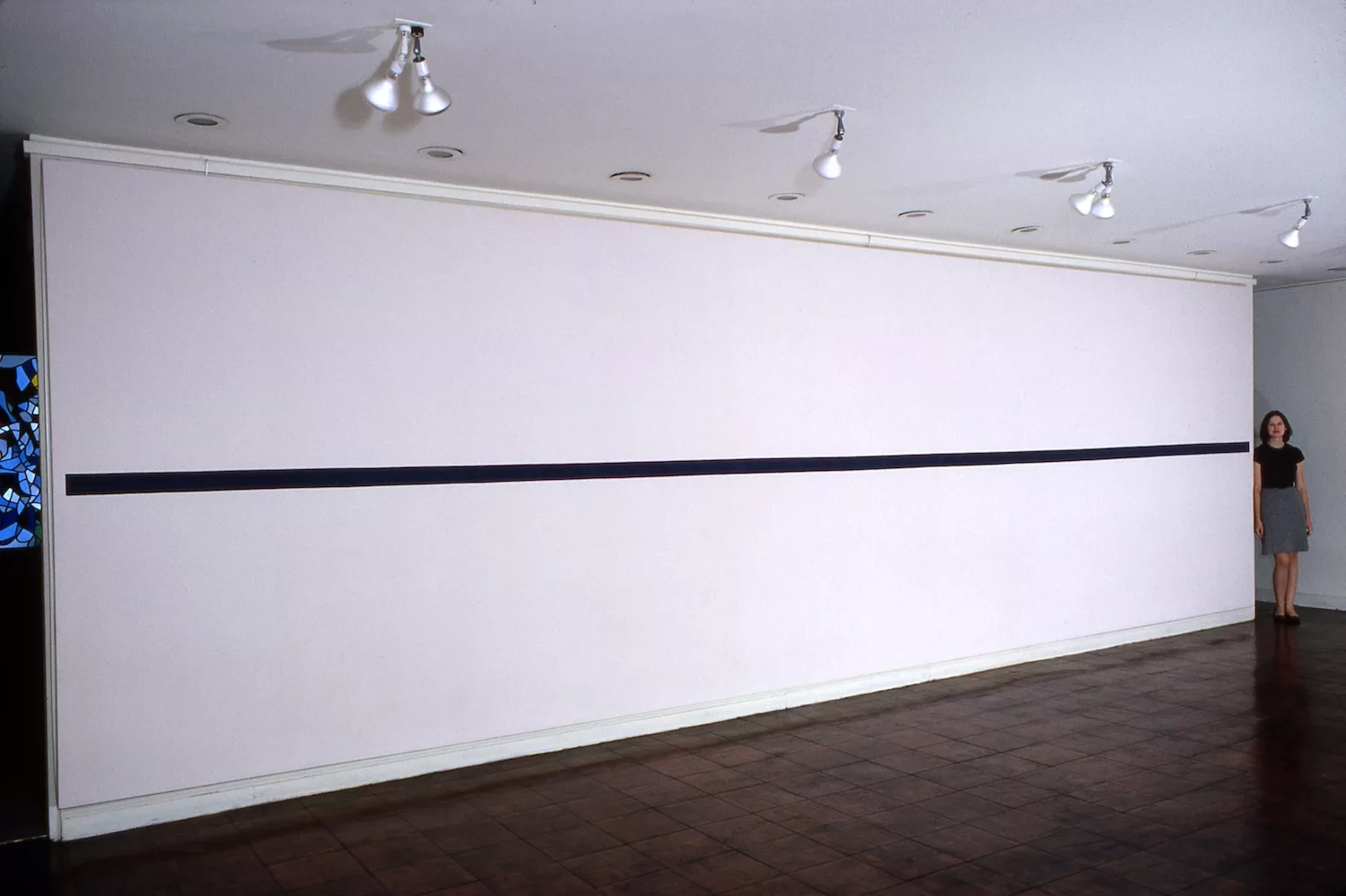

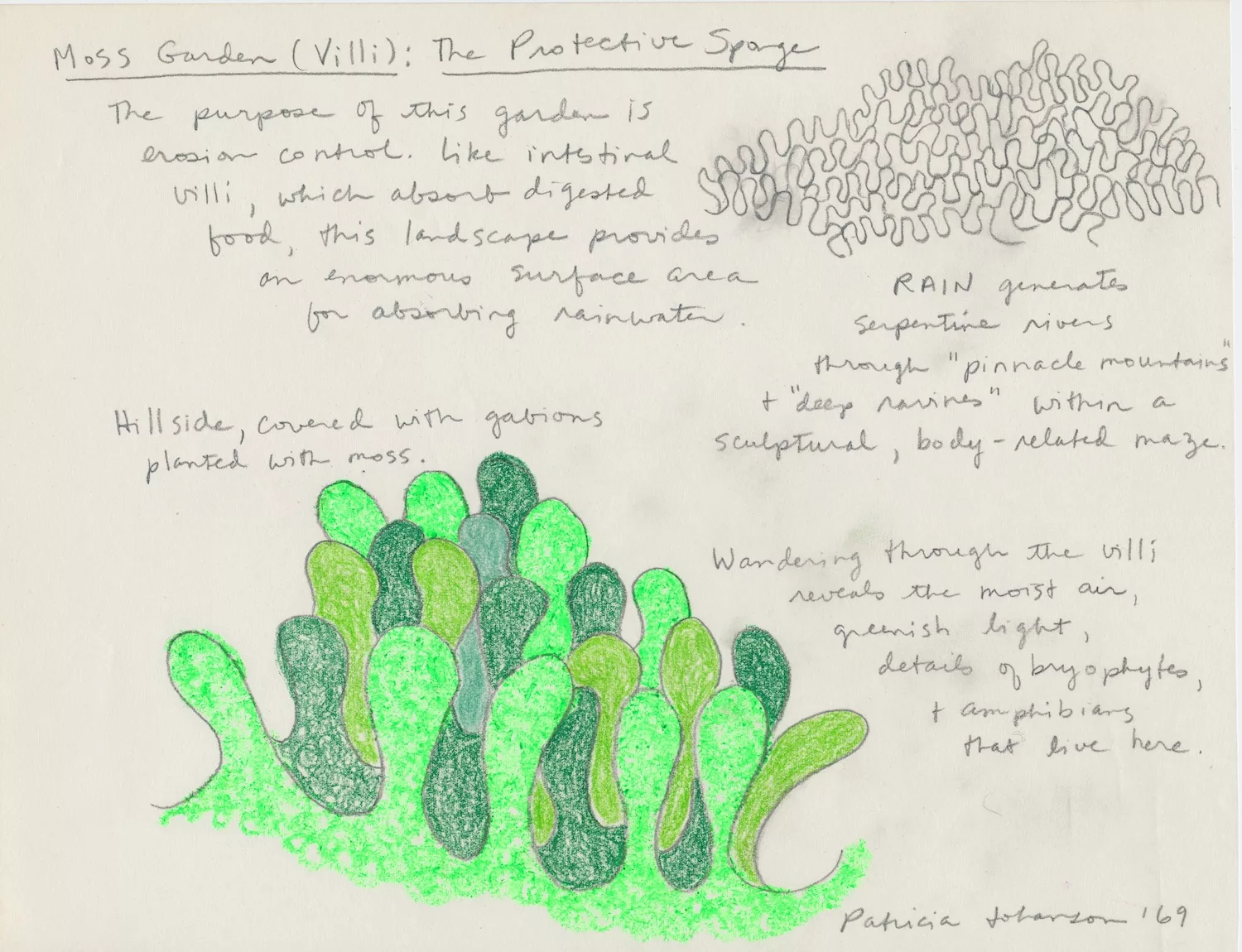

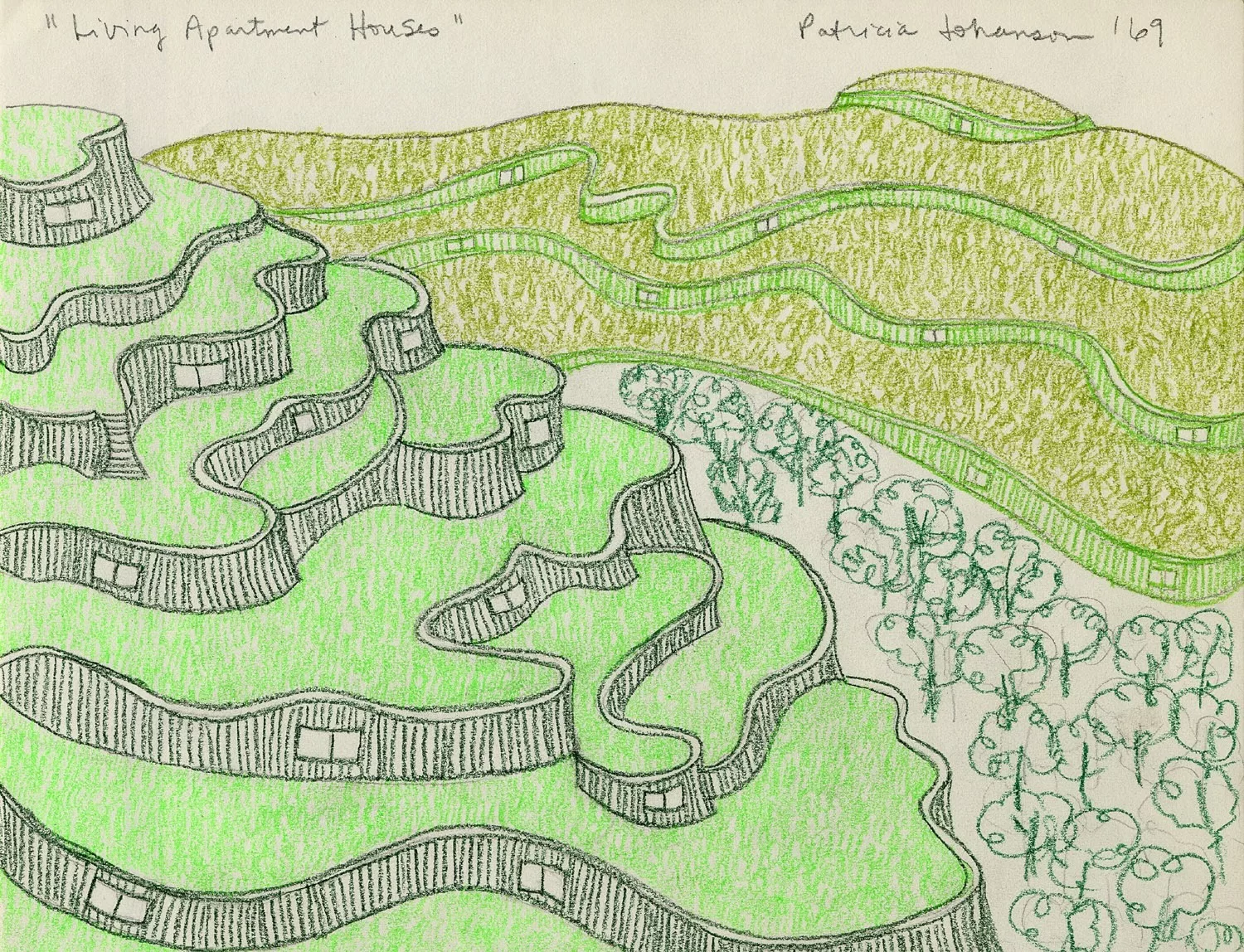

Painting was in fact the medium for which P. Johanson first attracted attention on her return from New Mexico. In 1964 she exhibited her first austere canvases alongside Minimalist artists, including Carl Andre (1935–2024) and Robert Barry (1936–). After being spotted at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York in 1967, her imposing painting William Clark, completed earlier that year, was shown at MoMA in 1968. Also in 1968, the media attention surrounding Stephen Long, a monumental 490-metre land art sculpture, attracted the interest of House & Gardenmagazine, which commissioned her to design a garden. A year later, P. Johanson delivered 150 drawings, structured according to function – nourishing, restorative, pollutant-removing, optical – and featuring forms and dynamics inspired by flowers, animals and insects. However, these avant-garde proposals ran counter to what the publication had anticipated.

Although none of these visionary drawings ever came to fruition, they represented a pivotal moment for the P. Johanson, who was committed to creating designs that could connect all members of the living world. To this end, she decided to further her education, and in 1977 she earned a degree in architecture from the City College School of Architecture in New York. In the early 1980s, recognising the potential of her approach, the director of the Dallas Museum of Art invited her to oversee the restoration of a brackish pond surrounded by the city’s museums, with an amusement park at one end. Leonhardt Lagoon, which took five years to complete (1981–1986), combines environmental care and user well-being, blending a restorative mission with educational objectives. This project was the first to seamlessly integrate ecological imperatives, social impact and aesthetic merit.

Much like the careers of architects, P. Johanson’s journey was marked by ambitious projects that never moved beyond paper or the maquette stage (Óbidos, Brazil, 1992; Nairobi, Kenya, 1995; Brockton, USA, 1997–1999; Millenium Park, Seoul, South Korea, 1999) as well as a handful of remarkable, monumental realisations in which water played a key role. In 1989, when diagnosed with terminal cancer and given a life expectancy of six months, she was in the midst of designing Endangered Garden along the shores of San Francisco Bay (completed in 1996). Following an unexpected remission in 1992, she began infusing her projects with a purpose focusing on the survival and protection of endangered species. Her design for a water-treatment site in Petaluma, California (2001–2009), was inspired by an endangered endemic mouse, a butterfly and a morning glory. There, working with engineers, she restored wetlands and agricultural areas and laid out 4.8 kilometres of hiking trails.

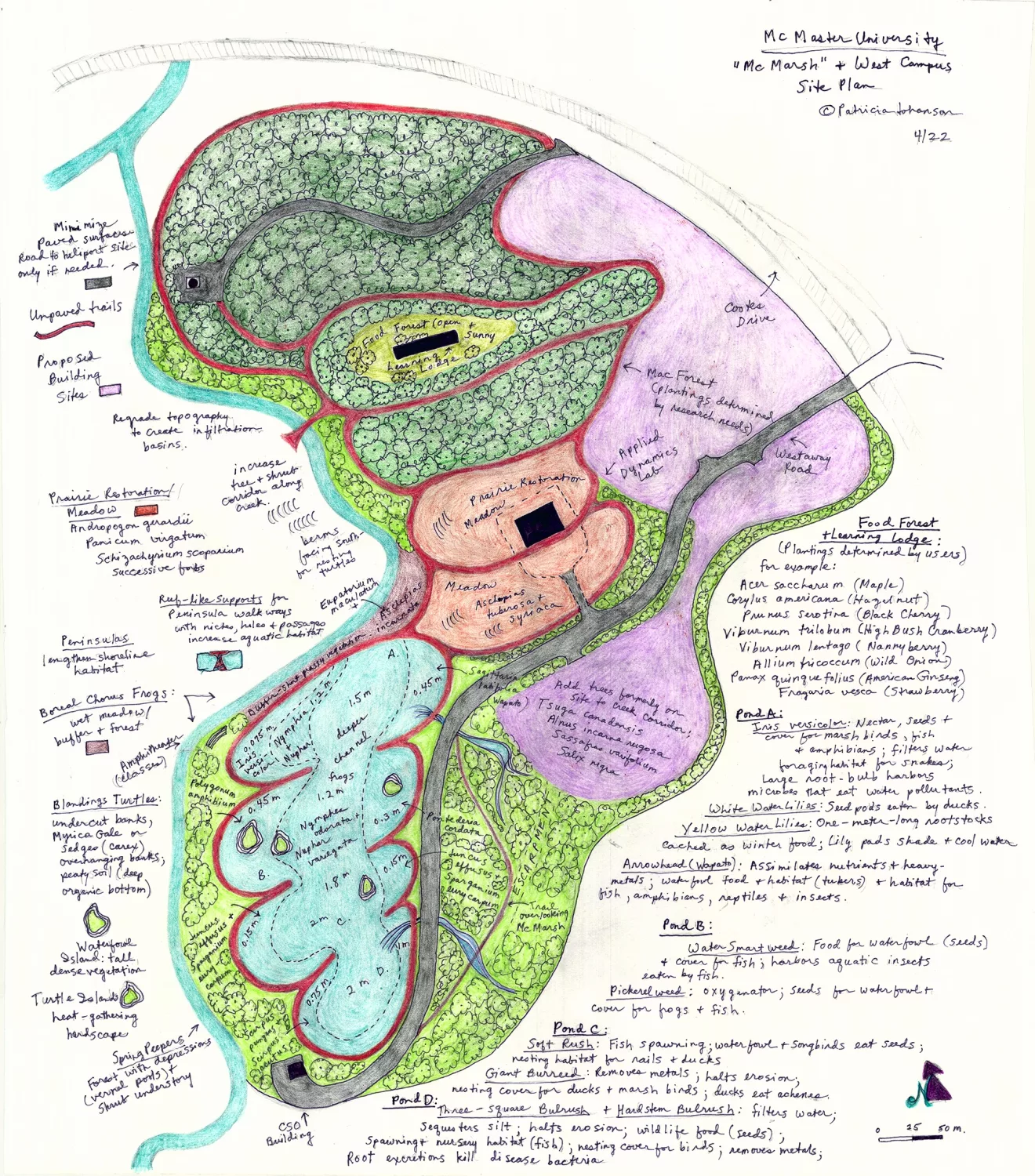

P. Johanson’s ability to engage effectively with scientists, construction supervisors, technicians and institutional bodies alike established her reputation as an exceptionally competent professional whose calm determination contrasted with the goals and scopes of the projects she brought to life. After completing The Draw at Sugar House in Salt Lake City in 2018, the culmination of fifteen years of work, negotiation and refinement, she focused on executing a project for McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada. Represented in just a few museums, including New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA and Washington, D.C.’s National Museum of Women in the Arts, she donated an early piece (Minor Keith, 1967) to the Art Institute of Chicago in 2023. Until her final days, she worked to set up a foundation in her name to ensure the preservation of her art.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Common Ground”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2026

Patricia Johanson and Fair Park Lagoon: Women of Land Art Symposium | Nasher Sculpture Center, 2023

Patricia Johanson and Fair Park Lagoon: Women of Land Art Symposium | Nasher Sculpture Center, 2023  No Man's Land: Women of Land Art with Patricia Johanson, Mary Miss & Leigh Arnold | Nevade Museum of Art, 2022

No Man's Land: Women of Land Art with Patricia Johanson, Mary Miss & Leigh Arnold | Nevade Museum of Art, 2022  Art That Heals the Earth with Patricia Johanson | Winsconcin Institute for Public Policy and Service, 2013

Art That Heals the Earth with Patricia Johanson | Winsconcin Institute for Public Policy and Service, 2013