Paula Santiago

Ratliff, Jamie, “Border Control: The Intersection of Feminism and Abjection in the Work of Paula Santiago”, SECAC Review XV, no. 4, 2009

→Laurel Reuter, “Paula Santiago: Moving into Light,” Septum, Los Angeles, Iturralde Gallery, 2002

→Zamudio-Taylor, Víctor, Paula Santiago, San Antonio, ArtPace, 1996

Paula Santiago. 1996-2002, Museo Amparo, Puebla, January–May 2008

→Paula Santiago, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey, Monterrey, April–August 2007

→MOAN, Iturralde Gallery, Los Angeles, 1999

Mexican sculptor.

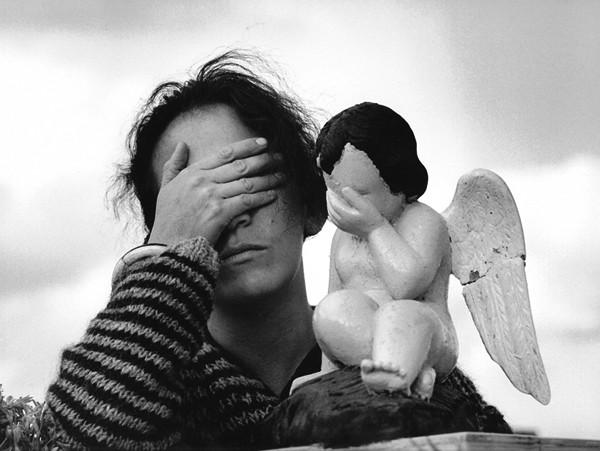

Paula Santiago’s sculptural practice engages in an ongoing conversation rooted in the ways the body intertwines with memory. Her most notable works merge pre-Columbian references with modern Mexican culture to offer reflections on time and emotion, connecting mind and body through her use of organic materials including her own blood and hair.

Although she originally pursued industrial engineering at the Universidad Panamericana, she travelled to Paris at the age of twenty-one to study literature and art history at the Sorbonne. While there she also received French, drawing, and painting lessons from private tutors. She briefly moved to London before returning to Mexico in 1996 where she continued her formal art training and submerged herself in the study of Mesoamerican art. P. Santiago set aside painting in 1992, deciding “I didn’t want to work with concepts, I wanted to work with my life”. She adopted the use of family heirlooms as materials for her artwork, including using handkerchiefs embroidered by her great aunt as canvases.

In 1996 P. Santiago won a six-week residency at the Artpace Foundation for Contemporary Art in San Antonio, Texas, where she experimented with organic materials and plastic forms. Sculptural rice paper, wax, flower petals, seeds, and her own blood and hair all became staple materials of the garments she is known for. Her sculptures from this period, such as Para protegerse de la Historia [To protect yourself from history], titled ANAM (1999), made from rice paper, human blood and hair, sequins and glass, play with presence and absence as they are filled by the emptiness of their missing wearers. Their forms draw a connection between contemporary sculpture and Mesoamerican objects while also evoking the fragility of these materials and their associations with decomposition. This work was included in P. Santiago’s solo exhibition, MOAN (the Mayan term for owl), at the Iturralde Gallery in Los Angeles in 1999.

P. Santiago was prevented from extracting her own blood after 2000 when she underwent treatment for cancer. She instead created work from her remaining blood drawings on rice paper covered with beeswax. One of these later works, Ch’ulel (2000), cites traditional indigenous tunics. According to Mayan belief, ch’ulel refers to a soul. The tunic is made out of rice paper, human hair, blood and wax, materials that carry with them what art historian Jamie Ratliff has referred to as “the artist’s own DNA, medical identity, and psychological status”. Her poetic sculptural reflections on Mesoamerican heritage paired with the ephemeral, fragile quality of her work evokes skin, while also signalling a protective armour from the past.

The artist has had retrospectives at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey (2007) and Museo Amparo (2008) in Mexico City. Her work can also be found in several museums

across the United States; for example, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art counts with De la serie: “Quitapesares 1” (1999) as part of its permanent collection.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022