Tamara de Lempicka

Mori Gioia, Tamara de Lempicka – Paris, 1920-1938, Paris, Herscher, 1995

→Blondel Alain, Lempicka. Catalogue raisonné (1921-1979), Lausanne, Acatos, 1999

→Mori Gioia (ed.), Tamara de Lempicka, la reine de l’Art déco, exh. cat., Pinacothèque, Paris (18 April–8 September 2013), Milan, Skira, 2013

Tamara de Lempicka, Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, 1989

→Tamara de Lempicka, symbole d’élégance et de transgression, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, Montréal, 1994

→Lempicka, Musée des Années Trente, Boulogne-Billancourt, 30 March–16 July 2006

Polish painter.

Born of a Russian Jewish father and a Polish mother, Tamara de Lempicka spent her childhood in St. Petersburg, Warsaw, and Lausanne. She maintained memories from her childhood of a life of a privilege, punctuated by prestigious soirées in the company of the cultured Saint Petersburg nobility. Shortly after her marriage in 1916 to the Polish lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki, she saw the easy happiness for which she was destined swept away by the 1917 October Revolution. Forced to flee the Bolshevik regime, the couple ended up in Paris, where Lempicka had to sell her jewelry to survive. She divorced her husband in 1928 in order to marry the baron Raoul Kuffner in 1933. In Paris, she frequented the ateliers of Maurice Denis and André Lhote. She came into her own style around 1925, when, encouraged by Count Emanuele di Castelbarco, a Milanese gallery owner, she painted 28 new paintings in six months, including thirty which were shown at the Bottega di Poesia gallery in Milan. Quickly becoming one of the most in-demand portrait artists, she completed a string of portraits of the haute bourgeoisie and the Italian and French aristocracy – like those of the Marquis of Afflito (1925) or the Duchess of Hall (1925). Aside from the important figures of the high society she wanted to conquer by painting, it was modernity itself that shines through as a theme of her work. The incredibly close framing and the theatrical look of some of the subjects in her paintings seem to come from the silent films of the early twentieth century. Contemporary architecture and the city—especially the skyscrapers of New York that fascinated her—serve as the background of her paintings.

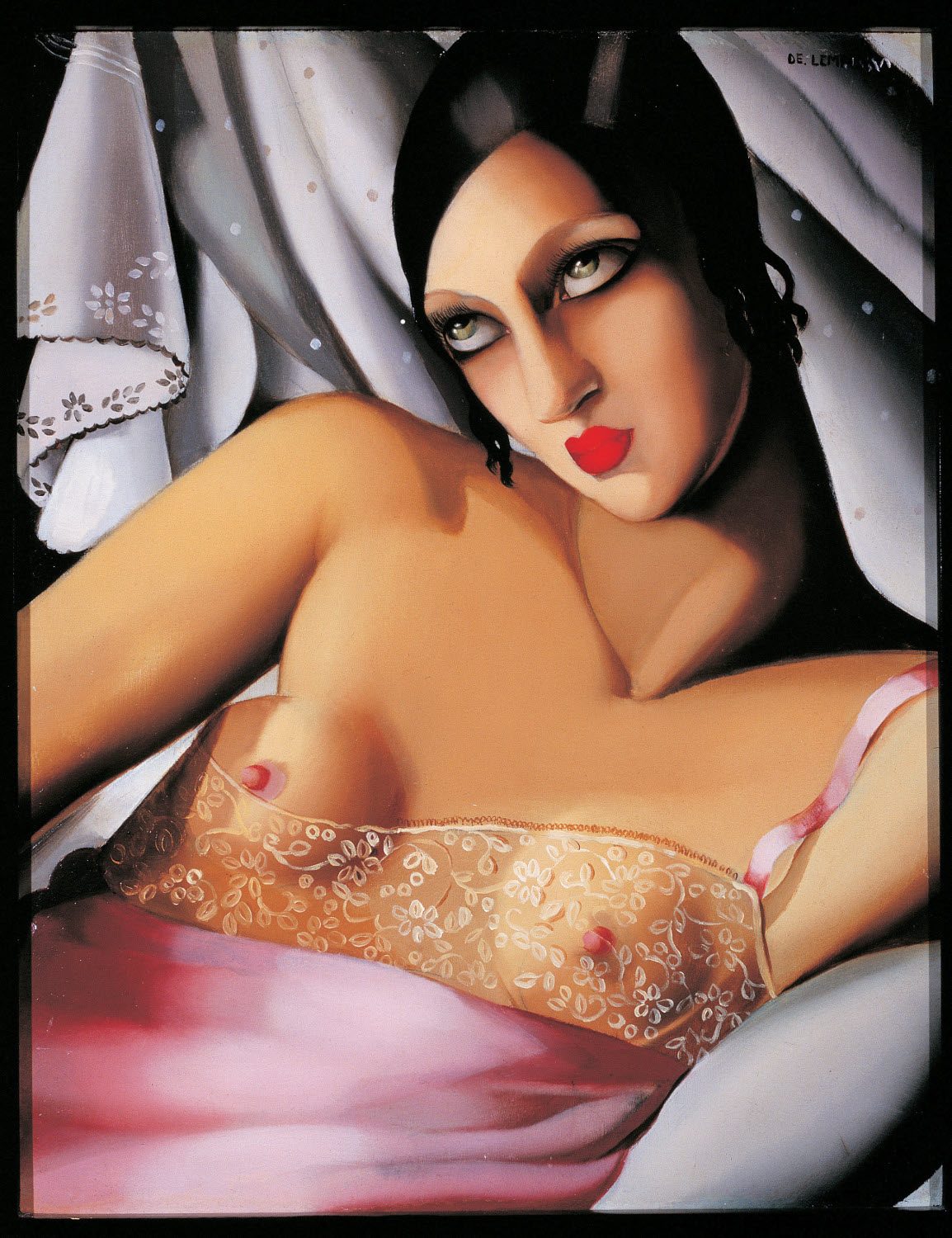

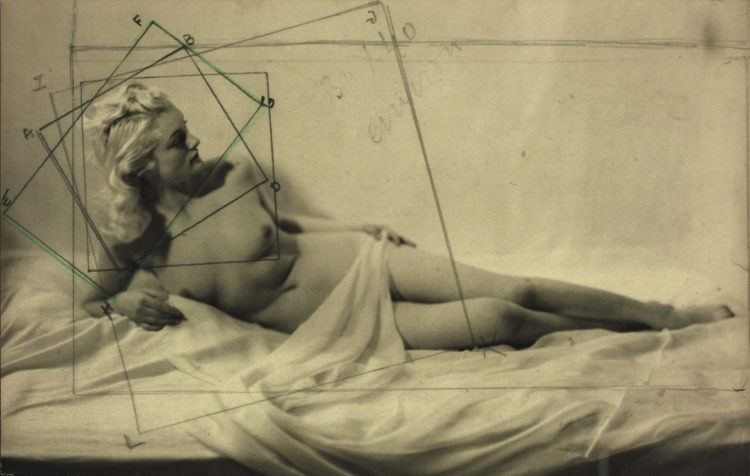

Her style, which combines neo-Cubism and the expressiveness of Italian Mannerism, was inspired by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, with an added touch of perversity. Her creative process was fascinating: although she produced almost no preparatory studies, her figures are modeled to perfection. The linea serpentina, the supreme expression of beauty for Italian theorists of the sixteenth century, animates the body and permeates her work with a surprising dynamism. In this way, the famous Portrait d’Andre Gide (c. 1925) reduces the subject to a “compressed charge of energy “, in the words of Germain Bazin, with his empty black eyes, unfettered by glasses, set in a twisted face. Her treatment of the subjects she depicted often translated their determination and sensuality, the latter of which is particularly on display as flirting often presided over her portrait sessions.

Claiming her bisexuality, the artist dared to paint women as few men did, similar to Gustave Courbet in the impudence and lasciviousness of her female nudes. A certain Rafaela posed for her for almost a year and served as a model for the famous painting La Belle Rafaela en vert (1927), whose sumptuousness of form, frank attitude, and dramatic lighting make it one of the most extraordinary nudes in the history of art. Often referred to as the “woman painter of women,” the artist confessed that it was her own portrait she painted through each piece. When asked for a self-portrait, she depicted herself in a green Bugatti, which she never owned, with luxury gloves and hat, borrowed from a photograph of the period. In this picture, entitled Mon portrait ou Autoportrait dans la Bugatti verte (1925), the artist becomes a true icon of the modern woman, mistress of fashion and speed.

Having moved to the United States at the beginning of World War II with her second husband, the painter was almost forgotten in Europe, which was uninterested in the world she portrayed. It was not until 1972, when an exhibit at the Luxembourg gallery in Paris rediscovered her works and reignited the passion for, in the words of Magdalene Dayot, “the improbable and certainly curious trinity of extreme modernism, of the purest classicism, and the most burning romanticism” that Lempicka embodies.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017