Polissena Nelli, en religion sœur Plautilla

Barker Sheila et Cinelli Luciano (ed.), Artiste nel chiostro. Produzione artistica nei monasteri femminili in età moderna [Artists in the Cloister. Artistic Production in Female Convents in the Modern Age], Florence, Nerbini, 2015

→Nelson Jonathan (ed.), Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588): the Painter-Prioress of Renaissance Florence, Florence, Syracuse University in Florence, 2008

→Nelson Jonathan (ed.), Suor Plautilla Nelli (1523-1588), The First Woman Painter of Florence, Washington, Cadmo, 2000

Navarro Fausta, Plautilla Nelli. Arte e devozione sulle orme di Savonarola [Plautilla Nelli: Art and Devotion in the Footsteps of Savonarola], exh. cat., Uffizi Gallery, Florence, March 8 – June 3, 2017, Livorno, Sillabe, 2017

Italian painter.

Polissena Nelli was born into a family of merchants. At the age of fourteen, she entered the Dominican convent of Santa Caterina da Siena in Florence, a religious house for women not far from the masculine convent of San Marco. Remaining there for the rest of her days, she served several times as its prioress.

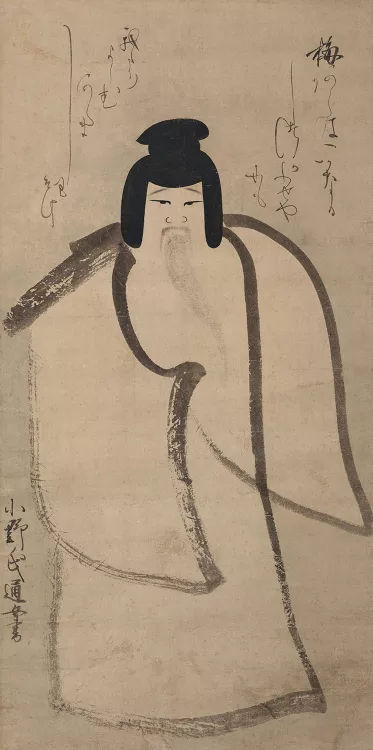

Although the artistic output of the Dominican friars – from Fra Angelico (1395–1455) to Fra Bartolomeo (1472–1517) – is well known, that of the Dominican nuns has received less attention. Sister Plautilla, as P. Nelli was known after becoming a nun, is nevertheless its most prominent figure. Upon her arrival, the convent was already a centre of artistic production in line with the precepts of its founder, Friar Girolamo Savonarola, whose portrait P. Nelli is thought to have painted after an earlier model. While he rejected worldly forms of art, the uncompromising reformer did encourage monks and nuns alike to practise drawing, painting and modelling in a range of materials, provided that their works were exclusively religious and of a simple, austere and didactic nature.

By the early sixteenth century, the convent had begun to receive an increasing number of young girls from artisan backgrounds, especially the book trade, who were eager to pursue miniature painting, panel painting or terracotta sculpture. Sister Plautilla received her arts training in this environment, possibly through direct interaction with the painters of San Marco, and certainly by working from Fra Bartolomeo’s drawings, cartoons and models, which were then kept at Santa Caterina. She also practised copying in the city, after the Florentine Mannerists, since strict enclosure for the nuns was not imposed until 1577.

Working at the edges of Mannerist conventions, P. Nelli developed a devotional style that adhered closely to the dictates of the Tridentine reform. She created pious images for the sisters’ contemplation, ranging from illuminated antiphonaries to major narrative scenes, such as a monumental Last Supper designed for the convent’s refectory (circa 1550–1558, now at the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella). At the same time, she also produced pieces intended for audiences outside the convent’s walls. She sold her works to churches and Florentine noble patrons, notably women whose daughters had taken the veil at Santa Caterina. These female connections significantly enhanced the convent’s standing, not only spiritually but also financially.

Though most of the works that 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari attributed to P. Nelli have been lost, a few major pieces have survived: besides her Last Supper, there is a Lamentation over the Dead Christ, likely based on cartoons by Andrea del Sarto (1486–1530) and now held at Museo di San Marco in Florence. In this Lamentation, it is clear from Christ’s anatomy that she worked with a female model.

Recent research, particularly the 2017 exhibition at the Uffizi, “Plautilla Nelli. Arte e devozione sulle orme di Savonarola” [Plautilla Nelli: Art and Devotion in the Convent in Savonarola’s Footsteps], has allowed specialists to begin reconstructing her corpus, which comprises altarpieces, small devotional paintings (Annunciations and figures of Dominican saints), hagiographic illustrations and drawings. This renewed interest in P. Nelli’s work has led to an extensive restoration of The Last Supper in the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella and highlighted the collective approach behind the nun’s artistic practice: she worked in a communal setting, following a monastic atelier model based on the repetition of archetypal forms. Indeed, she appears to have run a genuine workshop whose austere, Dominican-oriented output of holy images illustrated the Savonarolan revival influencing Florentine Dominicans in the Tridentine era.

A biography produced in partnership with the Louvre Museum.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025