Research

Unknown artist, Portrait of a Female Painter, Pupil of David, n.d., oil on canvas, 127 × 96 cm, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Courtesy of the Musée Marmottan Monet

In eighteenth-century Europe, clear rules marked the world of art – rules that were incontestably, unambiguously gendered.

How did one become an artist? By training with established “masters” and securing a position in the school of one of Europe’s increasingly exalted academies of art.

How did one acquire public recognition? By rising in the ranks of these schools, displaying pieces in these academies’ regular exhibitions, and perhaps even securing a coveted spot as an elected “Academician”.

How did one become a “master”? By developing a reputation in a particular genre, ideally history painting – considered the pinnacle of longstanding visual hierarchies of genre – and acquiring prestigious buyers for these large-scale works.

How did one become a history painter? By acquiring training in figure drawing, offered as an essential part of the curricula of these academic schools.

How did one gain admission to these schools? By various means, with one consistent thread: admission was predicated on being born male.

For more than a century, this story was embraced by conventional and feminist histories alike. But now, increasingly, research has shown that this framework is pitifully inadequate when it comes to explaining women artists’ experiences navigating this very same eighteenth-century world. While Academic rules certainly restricted women’s opportunities, these constraints failed to thwart women’s artistic ambitions or practices. Throughout Europe, and with parallels in the nascent United States, women pursued a range of paths in order to access an education in the arts – tuition that allowed them to professionalise in growing numbers.

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Self-portrait, 1786, oil on canvas, 100 × 80.5 cm, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe. © Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe

Spanning this pivotal historical era – one in which a series of political revolutions shook the foundations of Western societies to their core – women in fact became publicly acclaimed professional artists in unprecedented numbers, participating in the visual movements that defined the era alongside their male peers. They pursued rigorous training, exhibited their art in Academic shows, acquired prominent patrons and taught others in turn. They became Academicians, even though women were forbidden from enrolling in these Academies’ schools. And they became history painters, even though – supposedly – concerns of propriety barred women from studying the human body in live figure-drawing sessions. Across these years, women found ways to become artists in ever-rising numbers, especially in the two nations that boasted the largest and most established Academic systems: France and Britain.

Throughout the eighteenth century, France’s leading art institution was the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture [The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture], founded in 1648. From 1737, the Académie held an annual exhibition, the Salon, named for the room in the Louvre in which it initially took place; after 1747, it occurred every other year. Only elected members of the Academy were allowed to exhibit their art in these shows, and from its founding until 1791 the Academy elected only fifteen female members (who were nevertheless barred from its schools). In 1791, in the spirit of the early French Revolution, France’s new governing body, the National Assembly, declared the Salon “open” to all artists, regardless of gender or Academic status. In the first decade of this “open” Salon, more than one hundred female painters, sculptors and artists of other stripes exhibited their art; in the early decades of the nineteenth century, they were joined by more and more women (and men).

Mary Moser, Standing Female Nude, n.d., black and white chalk on grey-green paper, 49 × 30.2 cm, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

In Britain, women navigated a different cultural landscape. Throughout the early eighteenth century, British artists – particularly those based in London – nurtured a growing desire to establish a formal space for their profession, one that could parallel France’s Académie and the immense opportunities it provided for artists. In 1768, following a series of educational and exhibition ventures that showed both the need for a formalised space and a public audience eager to view and purchase works, a group of artists working in London – some British, others not – secured a royal charter from King George III to establish an official academy of their own. To establish this institution, they chose thirty-six founding members from amongst themselves: thirty-four men and two women, Mary Moser (1744–1819) and Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807). Unlike its French counterpart, they decided to accept artworks from Academicians and non-Academicians for what would become its annual show. When Britain’s Royal Academy of Arts held its first exhibition in 1769, four women contributed eight of the 136 pieces on display. By the end of the century, more than two hundred women had exhibited their work on the Academy’s walls, regularly participating in what had quickly become Britain’s most prominent and prestigious artistic venue. As in France, these numbers continued to grow. Ultimately, from 1760 to 1830, women contributed an average of 7–12 per cent of the works on display at the Academy and Salon – a higher proportional presence than women artists can claim in leading European and American museums today, where works by women typically average less than 5 per cent of pieces on display.

How did these hundreds of women become artists while being denied access to what was, purportedly, the essential pathway to artistic training and, thereby, success? Remarkably, research continues to reveal that in both nations, women’s educational trajectories mirrored those of their male peers – their tutelage simply took place outside of Academy-sanctioned spaces. In Britain, the vast majority of female artists who exhibited at the Academy (71 per cent) hailed from artistic families (families in which at least one other member, male or female, was a practising artist); a clear minority (17 per cent) studied with a male teacher who was not a family member.1 In stark contrast, in France, most of the women who exhibited at the Salon (72 per cent) could claim the same primary path to the Salon as their male peers: studies with a male teacher who was not a family member. Less than a third (29 per cent) of Paris’ female exhibitors were born into a family with a male or female artist.2

Alfred Edward Chalon, Students at the British Institution; with Artists Copying from Pictures on the Wall, 1805, pen and brown ink with watercolor on paper, 31.5 x 53.1 cm, British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

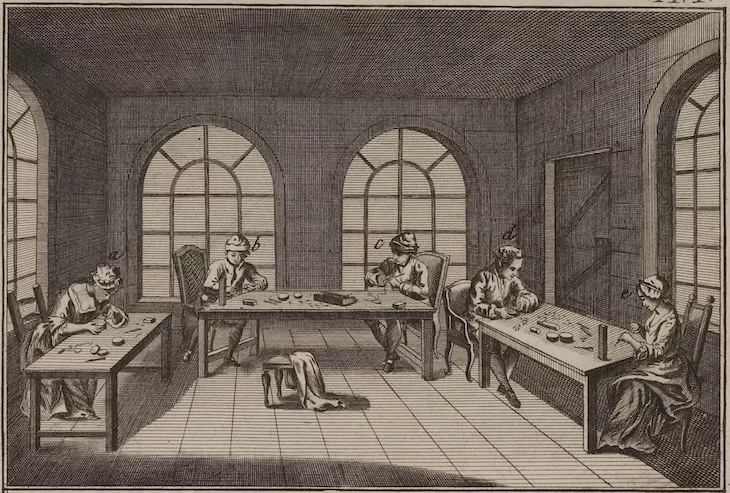

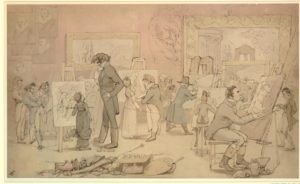

The intricacies of these diverse lessons remain hazy, obscured by centuries of selective scholarly practices that gradually removed women artists from the lessons that history continues to proffer. But hints survive. In London, the family-oriented nature of women’s backgrounds seems to have fostered intense commercially-oriented training within the home. The Academician Philip Reinagle trained four of his daughters to become landscape painters, using lessons that included copying parts of “Old Master” paintings on display at the British Institution (another art society, founded in 1805); his peer Joseph Farington recalled, “They work very quick, & said, ‘Picture painted one day; sold the next; money spent the third.’”3 A satirical watercolour from 1805 shows such a scene at the British Institution, with an intermingled pack of painters – including Fanny (1786–1831) and Charlotte Reinagle (1782–1822) – copying from works on display. The diary of the painter Ellen Wallace Sharples (1769–1849) offers other clues into what could constitute home-based training; under her watchful eye, her daughter Rolinda Sharples (1793–1838) copied from works by family members, imagined scenes described in Roman history books and studied anatomical publications. These lessons spanned media and genres; the sculptor and wax-modeller Catherine Andras (1775–1860), who debuted at the Academy in 1799 and became the official wax modeller to Britain’s Queen Charlotte three years later, could claim the miniaturist Robert Bowyer as her adopted father.

Angelica Kauffman, Design, 1778–1780, oil on canvas, 126 × 148.5 cm, Royal Academy of Arts, London. © Royal Academy of Arts, London; photographer: John Hammond

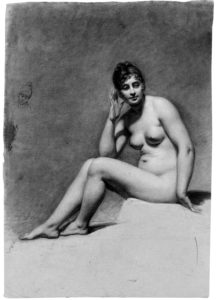

As hinted by Ellen Sharples, several British women sought out ways to study the human figure. For Rolinda Sharples, this seems to have been limited to anatomical prints. Others copied from plaster casts, sculptures, drawing books and even – it appears – the occasional live model in private settings. A rare surviving drawing by Mary Moser shows a standing nude woman, whose specific, non-idealised features imply that Moser sketched her form from life. Whether Angelica Kauffman, who was widely recognised as a history painter, studied models from life continues to be a subject of debate.4 Yet in her figure of Design , painted for the ceiling of the Royal Academy’s headquarters, she immortalised one clear path by which women could learn to depict the human form: by rendering classical statuary. Soon, several women would gain notice for exhibiting historical scenes at London’s Academy, from Maria Cosway (b. Hadfield; 1760–1838) in the closing decades of the eighteenth century to Mary Anne Ansley (b. Gandon; fl. 1814–, d. 1840), and Harriet Jackson (later Browning; fl. 1803–34) in the opening decades of the nineteenth. Although no paintings by A. Ansley or H. Jackson are known to survive, reviewers explicitly noted how each painter exhibited canvases that included successfully rendered nudes.

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Self-portrait with Two Pupils, Marie-Gabrielle Capet and Marie- Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond, 1785, oil on canvas, 210.8 × 151.1 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Julia A. Berwind, 1953

We know even more about such opportunities in France, where the records reveal a gradual opening of studios and opportunities to female practitioners from the 1780s onwards, and especially following the opening of the Salon in 1791. In prior decades, women acquired training on a somewhat ad hoc basis, largely through family connections to established artists. Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803), both admitted to the Académie in 1783, exemplify this trend: initially trained by her father, E. Vigée Le Brun went on to study with his friends after his early death; A. Labille-Guiard trained with François-Élie Vincent, a family friend, and later married his son.5

Following these painters’ joint admission to the Académie – though any direct correlation remains unknown – more and more women began to pursue training with France’s leading artists. A. Labille-Guiard trained at least thirteen women, including Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761–1818) and Marie-Marguerite Carreaux de Rosemond (1765–1788), the two she famously depicted in a monumental self-portrait exhibited at the 1783 Salon (fig. 4). But most of all, women studied with established male painters: in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, more than 180 women took lessons in the studios of more than 100 male artists. More than twenty women passed through Academician Jacques-Louis David’s atelier, fifteen of whom went on to exhibit in public shows; at least one of J.-L David’s female pupils exhibited at every Salon from 1791 until 1837. The Academician Jean-Baptiste Regnault instructed an unmatched thirty-four exhibiting women.6

Pauline Auzou, A Seated Female Nude, n.d., black-and-white chalk on blue paper, 58.3 × 40.4 cm, private collection. © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

In these studios, female pupils learned their teachers’ specialties. In the case of J.-L. David and J.-B. Regnault, this meant conventional, traditional history painting – and seemingly the figure training that this specialisation implied. Two paintings show women copying from J.-L. David’s celebrated historical canvases: one is by an unknown artist, while the other, from 1786, is a self-portrait by his student Marie-Guillemine Benoist, who would go on to exhibit historical works and execute numerous canvases for Napoleon and his government. In a published memoir, one of J.-B. Regnault’s pupils from 1793–1794 recalled how the members of his female atelier – safely sequestered in the painter’s inner Louvre chambers – practiced portrait and genre painting for up to eight hours each day. Drawings by J.-B. Regnault’s students, including Pauline Auzou (b. Desmarquest; 1775–1835, also the future beneficiary of Napoleonic patronage), suggest that this training included figure drawing lessons. Even women unaffiliated with established studios appear to have found ways to access such treasured tutelage; sketches by the Polish painter Anna Rajecka (1762-1832) that recently came on the art market testify to a figure drawing session with a male model, fully nude apart from his mid-section.

Women’s multifaceted educational pathways in the eighteenth century – intersecting with, diverging from, and inadvertently supported by an Academic system that continued to place their works on prominent display – would set the stage for female artists to nurture increasingly ambitious artistic aspirations. Soon, one of J.-L. David’s own students would astound early nineteenth-century viewers with her command of the historical genre. In 1804, when the Salon instituted a prize system under Napoleon, his pupil Angélique Mongez (1775–1855) won the sole first-prize medal awarded. Her winning piece was a large-scale, classical history painting of Alexander the Great – one of hundreds of works that tell a remarkably different narrative of art than the account we have inherited. Unfortunately, A. Mongez’s canvas is not currently known to survive. Perhaps it has been lost, misattributed, or left to linger in museum storage alongside countless others by her once-recognised predecessors and peers.

For male artists and artistic families, see Martin Myrone, Making the Modern Artist: Culture, Class and Art-Educational Opportunity in Romantic Britain (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2020).

2

For all statistics for female artists in this paragraph, see Paris A. Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 (London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art / Yale University Press, 2022), Chapter 2, tables 2.1 and 2.2.

3

Kenneth Garlick, Angus Macintyre, and Kathryn Cave, eds., The Diary of Joseph Farington, 16 vols. (New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art / Yale University Press, 1978–84), vol. 8, 3106 (15 August 1807).

4

See, for instance, a drawing by Kauffman in the British Museum, Pp,5.151.

5

They followed in the steps of other eighteenth-century luminaries including, Marie-Thérèse Reboul Vien (1735–1805), Marie-Suzanne Giroust Roslin (1734–1772) and Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818). For Vigée Le Brun see in particular Mary D. Sheriff, The Exceptional Woman: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun and the Cultural Politics of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); for Labille-Guiard, see in particular Laura Auricchio, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009). Their peer, the sculptor Marie-Anne Collot (1748–1821), pursued a similar path with less recognition; from her work as an artist’s model, she came to study with Étienne Falconet, progressing from terracotta to marble. In 1766, she joined Falconet on his sojourn to Russia where they both undertook projects for Catherine the Great and other members of the Russian elite.

6

For all statistics in this paragraph, see Spies-Gans, A Revolution on Canvas, Chapter 2.

Paris A. Spies-Gans is an art historian with a focus on women, gender and the politics of artistic expression. She is the author of A Revolution on Canvas: The Rise of Women Artists in Britain and France, 1760–1830 (2022) as well as articles in The Art Bulletin, Eighteenth-Century Studies and more. She holds a PhD in History from Princeton University and an MA in Art History from the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her research has been supported by fellowships from several generous institutions, including the Harvard Society of Fellows and the J. Paul Getty Trust.

Paris A. Spies-Gans, "Restricted, but not Deterred: How Women Became Artists in the Rulebound Eighteenth Century." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/empechees-mais-pas-decouragees-comment-les-femmes-sont-devenues-artistes-malgre-les-entraves-au-xviiie-siecle/. Accessed 12 July 2025