Rosemarie Trockel

Frenssen Birte (ed.), Rosemarie Trockel : groupement d’œuvres 1986-1998, exh. cat., Hamburger Kunsthalle, Cologne (4 September – 15 November 1998) ; Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (4 December 1998 – 7 February 1999) ; Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, Stuttgard (13 March – 23 May 1999) ; M. A. C. Galeries Contemporaines des Musées de Marseille, Marseille (25 June – 3 October 1999), Marseille/Cologne, Musée de Marseille/Hamburger Kunsthalle, 1998

→Storsve Jonas (ed.), Rosemarie Trockel, dessins, exh. cat., cabinet d’art graphique, Centre Pompidou, Paris (11 October 2000 – 1 January 2001), Paris, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2000

→Rosemarie Trockel. Flagrant Delight, Paris, Les Presses du réel, 2013

Rosemarie Trockel, Sammlung Goetz, München, 27 May – 26 October 2002

→Rosemarie Trockel: post-menopause, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 29 October 2005 – 12 February 2006; Museo nazionale delle arti del XXO secolo, Rome, 19 May – 19 August 2006

→Rosemarie Trockel : un cosmos, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, 23 May – 24 September 2012; New Museum, New York, 24 October 2012 – 13 January 2013; Serpentine Gallery, London, 2013; Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublick, Bonn, 28 June – 29 September 2013

German visual artist.

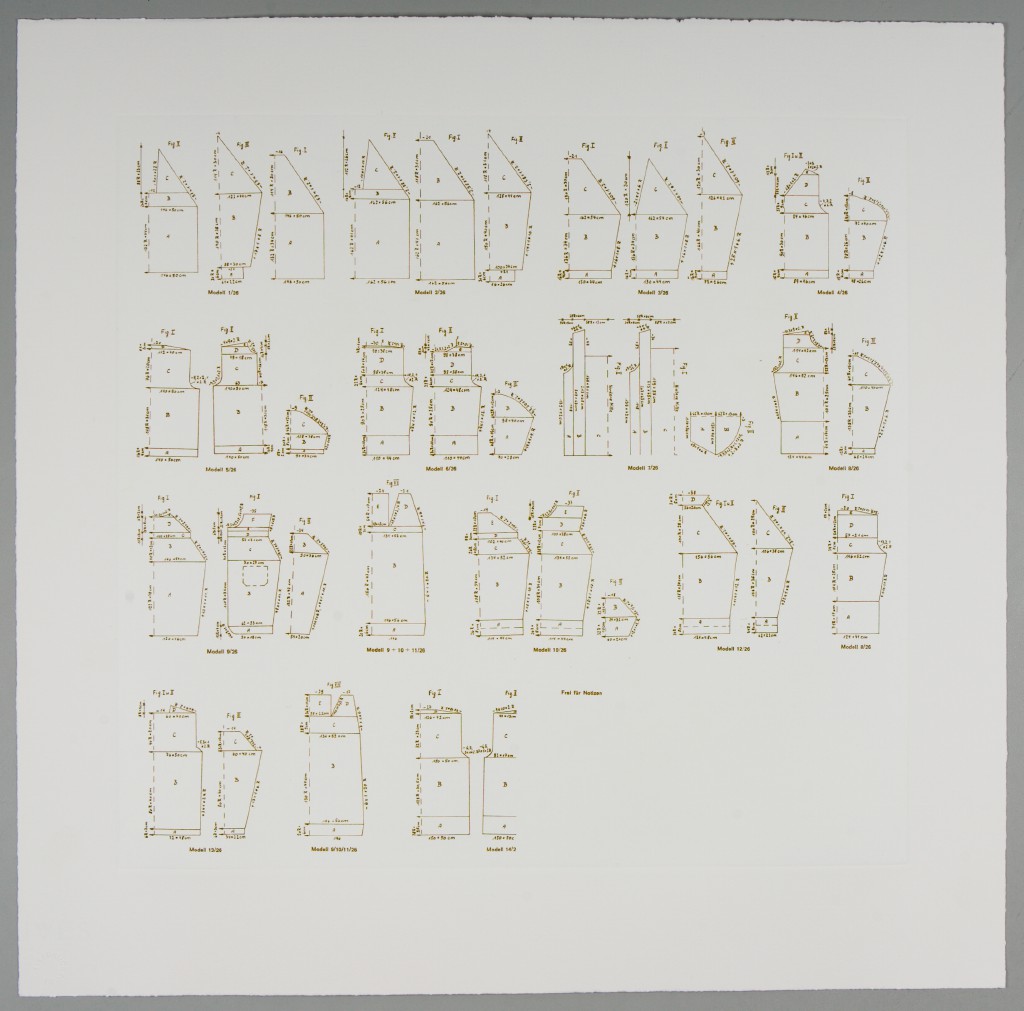

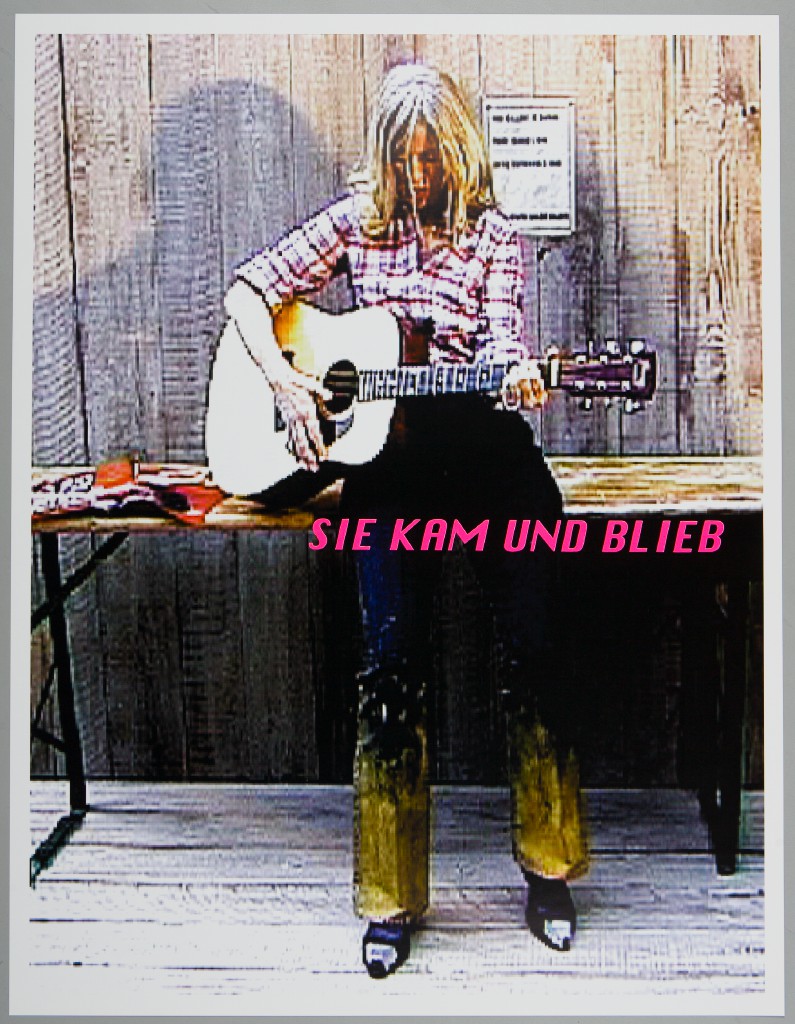

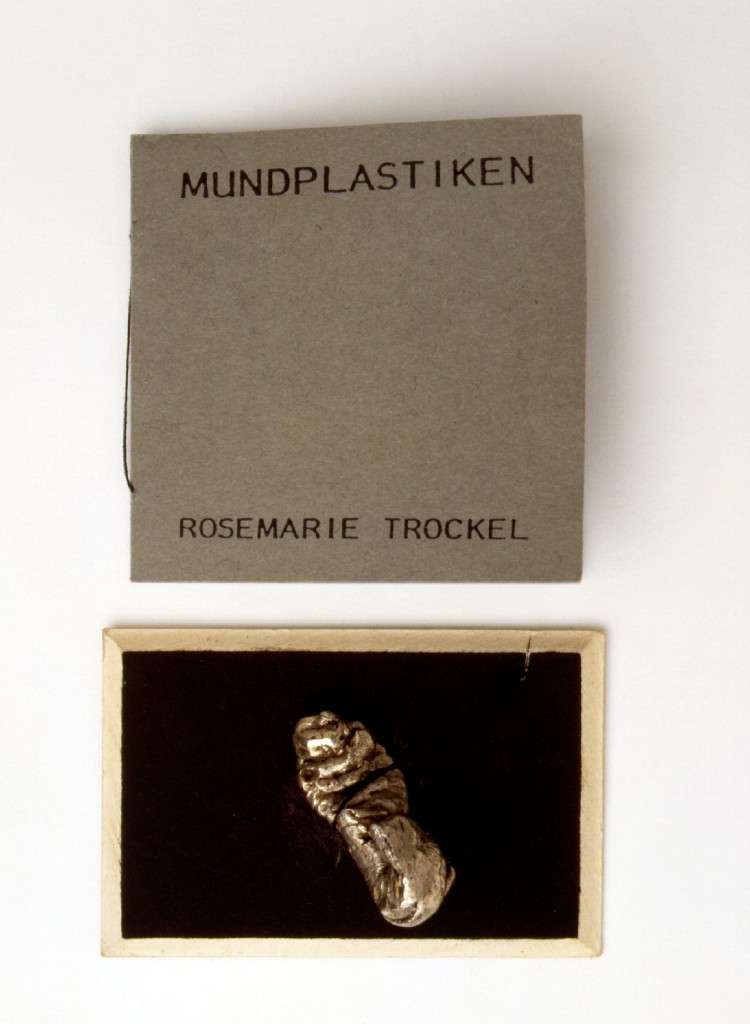

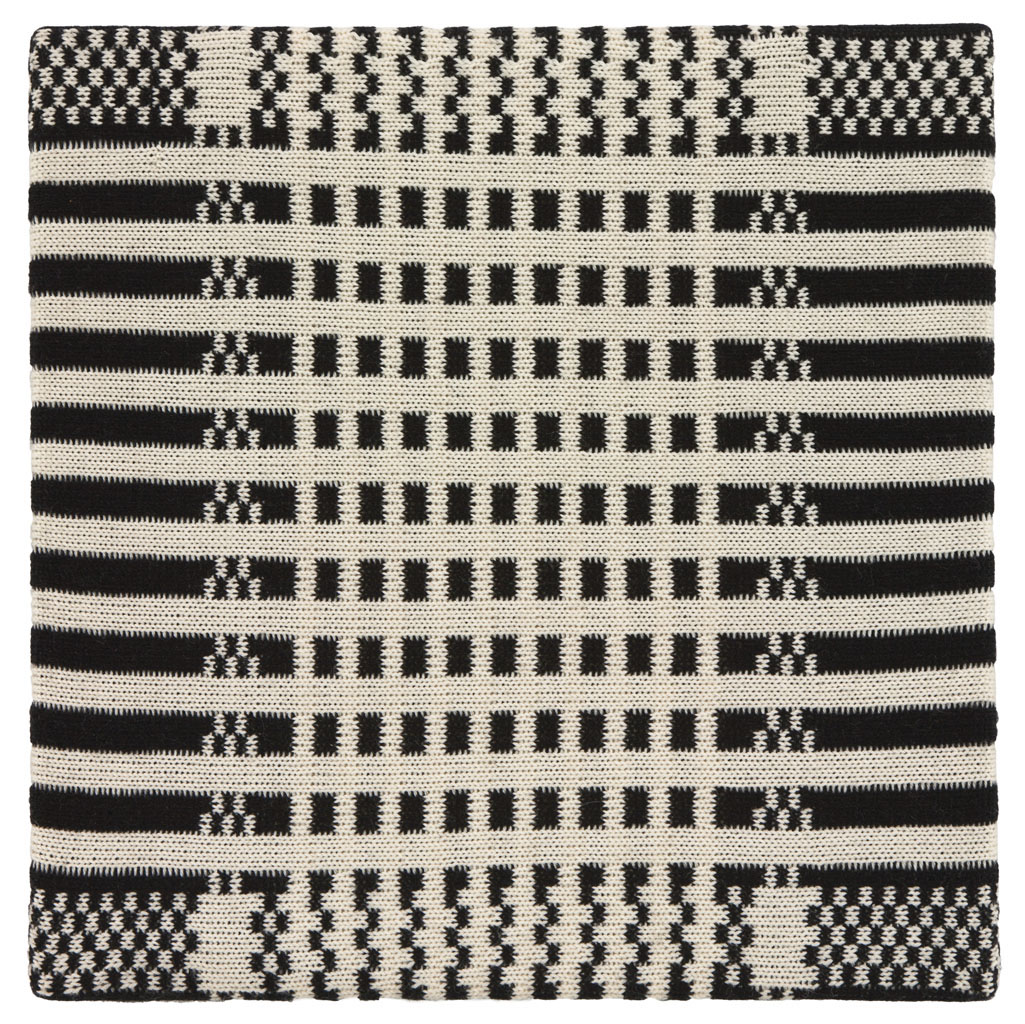

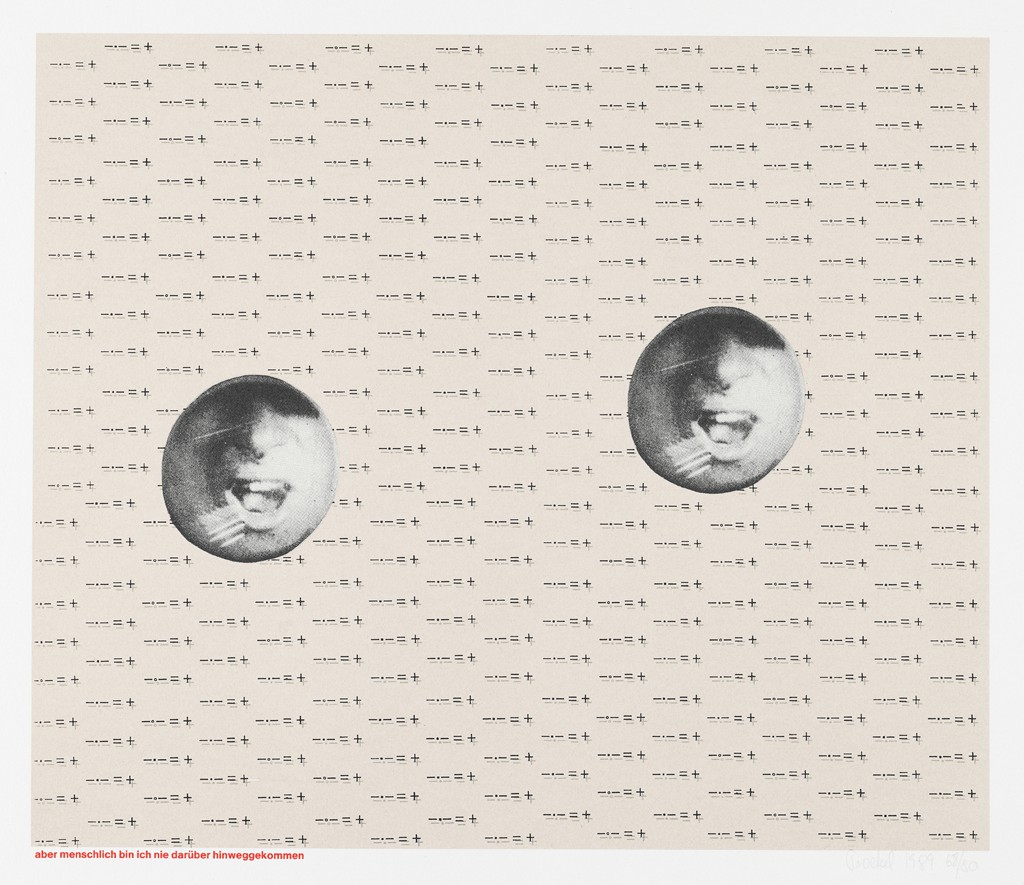

Often figurative, the highly referential works of Rosemarie Trockel can be read on many different levels, and are at times difficult to grasp, yet she always follows the same line of thought: critiquing representation and revealing a gap from reality; making social and artistic hierarchies visible; and exposing their trivial nature. From drawings, to sculptures, installations and films, her practice has been extremely varied since she began working in the 1980s. She is as ironic about consumer society as she is about artistic and sexual representations. The knitting stretched on canvas, Cogito, ergo sum (1988) reclaims two triumphant affirmations from the history of thought: a quotation by Descartes on one hand, and Malevich’s black square on the other. By juxtaposing these elements, she reveals their common thread: both were articulated by men of dominate positions in society. Through knitting, she simultaneously belittles this overexaggerated masculine ego and restores a complimentary place to that of the feminine – often forgotten in order for the masculine to exist. In R. Trockel’s body of work, she indeed asserts a feminine perspective, questioning the differences between that which is considered noble creation and that which is considered ornamentation. In fact, she was trained in a school of applied arts, the Werkkunstschule in Cologne, between 1974 and 1978. The question of the decorative is found throughout her work, for example in the drawing entitled Ornement (2000), in which a masculine body is presented in a contortionist pose, exposing his genitals in the centre of the composition. Here, ornamentation is charged with eroticism and violence, far from her usual associations.

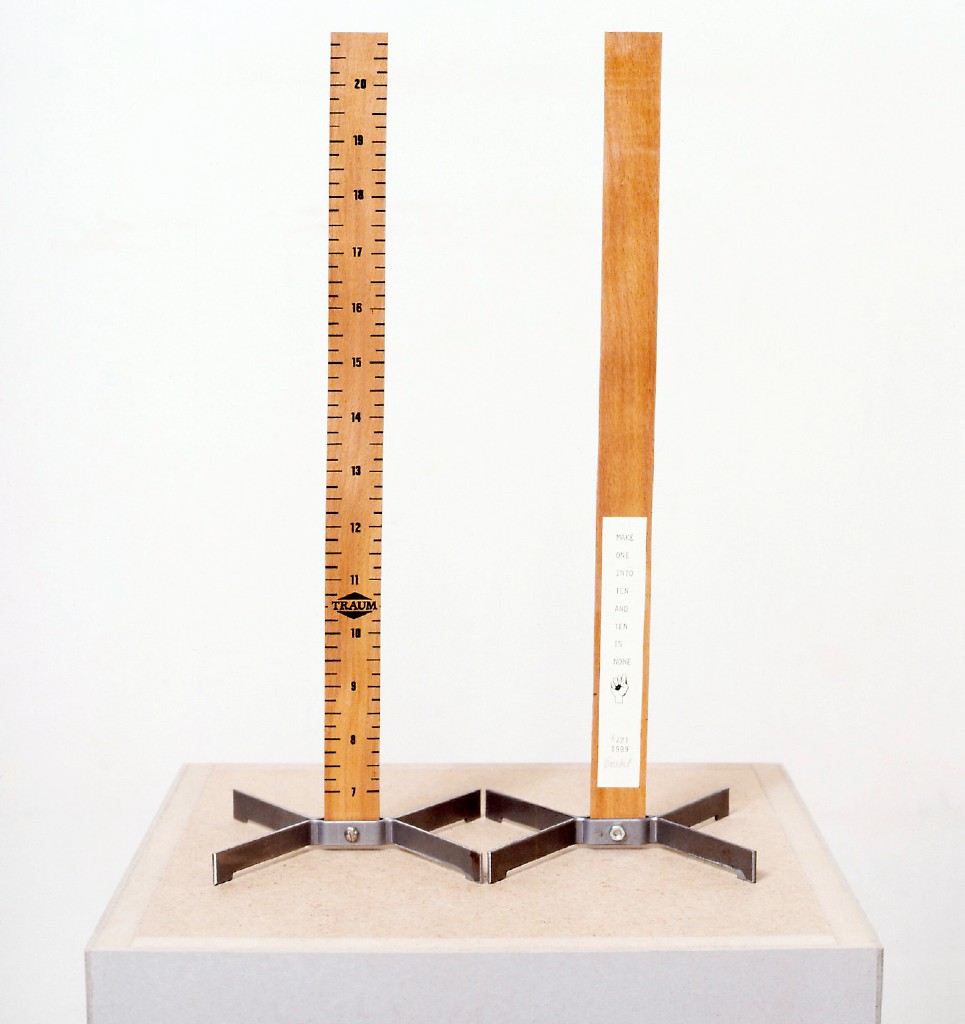

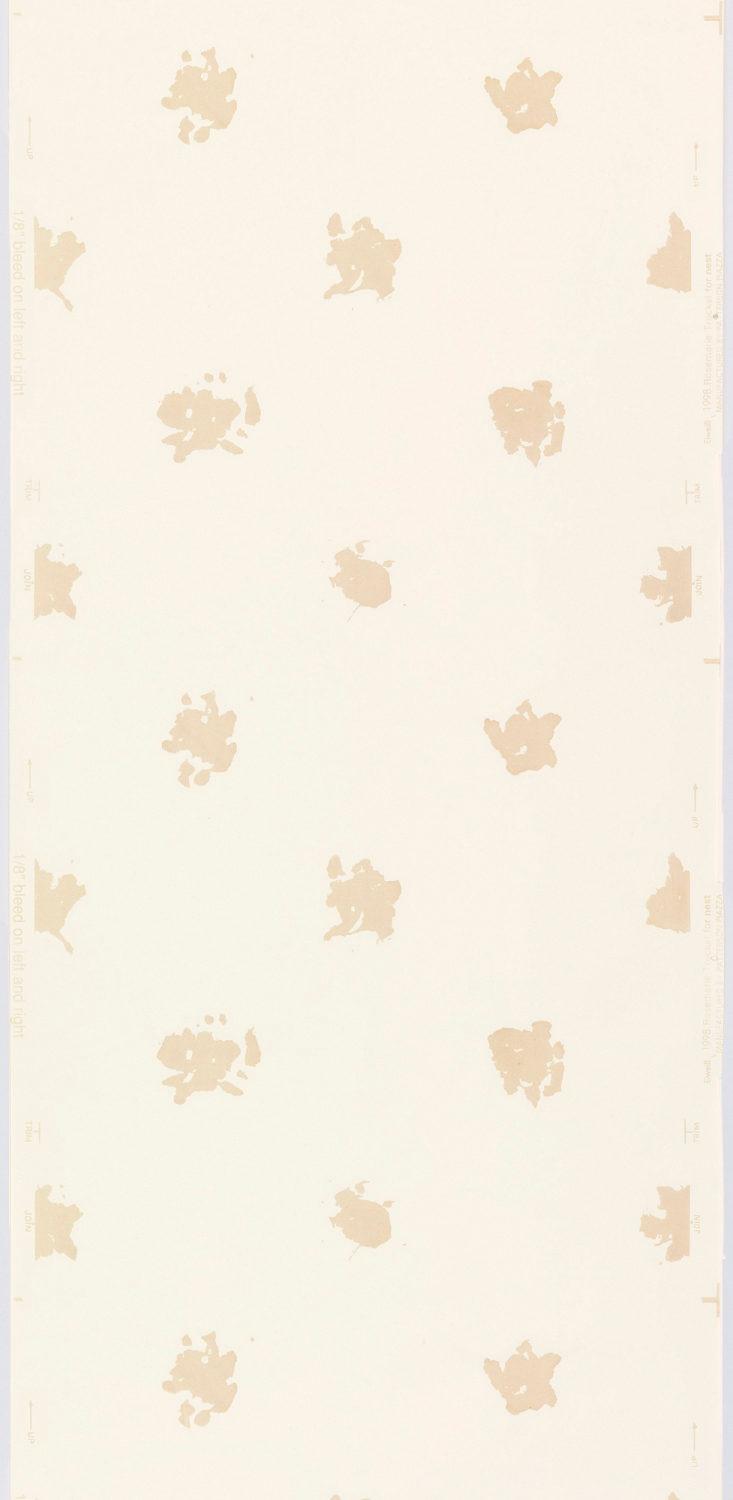

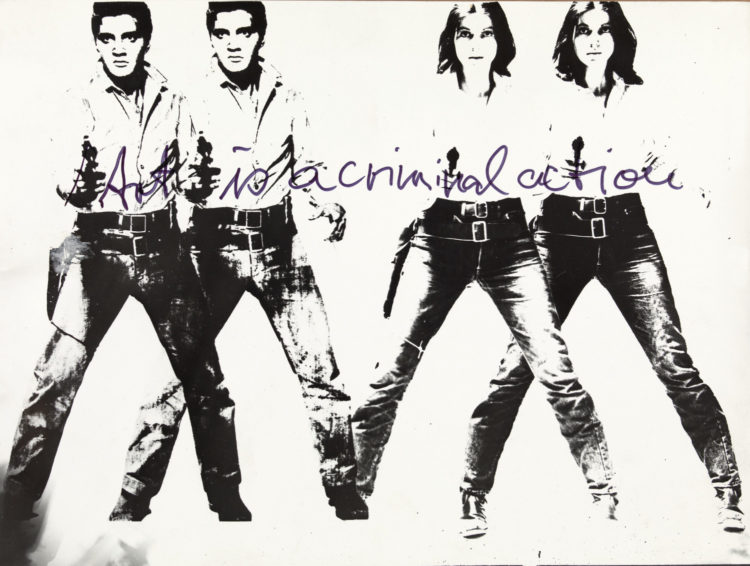

In 1984 she returned to an artistic context through painting, and became known for her wool works. Typically rich in meaning, the Woolmark logo, the Playboy bunny, the hammer and sickle, and the swastika are motifs that repeat endlessly in these works. This decontextualization and reiteration removes all substance from them, erecting them as “logos”, the only status granted to representation in our society of the image, according to Peter Weibel. At the same time, the works stand apart from the logic of mass production, as they are knitted by computer-controlled machines that produce patterns by R. Trockel – the machinery produces unique pieces. These “knitting pictures” reference art of the twentieth century, from the work of Niele Toroni and his methodical repetition of regular motifs, to that of Andy Warhol and the multiplication of pop images. This also extends into the fabrication of her woollen garments, such as her balaclavas or jumpers with two head-holes. From 1987, R. Trockel adopts yet another traditional social status symbol of the woman into her work – the hot plate. Unambiguous in its materialisation of the duties of the housewife, the hot plate is diverted from its typical function and presented vertically in compositions evoking minimalism and op art. Thus, the contrast between the heating function of the object and the cold manner in which it is displayed is made salient. Yet another accentuated contrast is that the plate, while a tool, resembles a fragmented female anatomy: thus both breasts and Marcel Duchamp’s infamous Prière de toucher are evoked by the work (Untitled, 1993). The question of the portrait is essential in the work of R. Trockel, as she introduces the gaps that interest her. Sometimes the portrayed model is a monkey with strangely human expressions (Untitled, 1985). At other times representations of each of her family members prove to be, after analysis, a general commentary on the discoveries of Freud (Gipsmodelle + Entwürfe, [plaster models and drawing], 1994–1995). Elsewhere, double portraits in pencil, or photocopied, reassemble gender and its connotations. She even merges her own face with that of her partner, Andreas Schulze, in a work from 1992. In the series B.B. from 1993, the features of Brigitte Bardot, symbol of sexual liberation, meld into those of Bertolt Brecht, and multiple other lovers. R. Trockel represented Germany in the Venice Biennial of 1999.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Rosemarie Trockel – Flagrant Delight

Rosemarie Trockel – Flagrant Delight