Minosaki, Akiko, Shashinshi Shima Ryū: Nihonhatsu no josei fotogurafua [Photographer Ryū Shima: Japan’s First Woman Photographer], Tokyo, Kōseisha, 2025

→Murakami, Yōkō, Genji gannen haru, Shima Ryū wa shashin satsuei o [In the Spring of 1868, Ryū Shima Photographed], Tokyo, Nihon Shashin Kikaku, 2019

→Shima Kakoku to Shima Ryū: Bakumatsu no Shashinshi fusai [Kakoku and Ryū Shima: Husband and Wife Photographers of the Bakumatsu Period], exhi. cat., Gunma Prefectural Museum of History, Takasaki, 2007

Dai-81-kai kikakuten, Shima Kakoku tanjō 180-shūnen kinenten –“Shima Kakoku to Shima Ryū: Bakumatsu no Shashinshi fusai” [81st Special Exhibition, Commemorating the 180th Anniversary of the Birth of Kakoku Shima: “Kakoku and Ryū Shima: Husband and Wife Photographers of the Bakumatsu Period”], Gunma Prefectural Museum of History, Takasaki, 21 April – 3 June 2007

Japanese photographer.

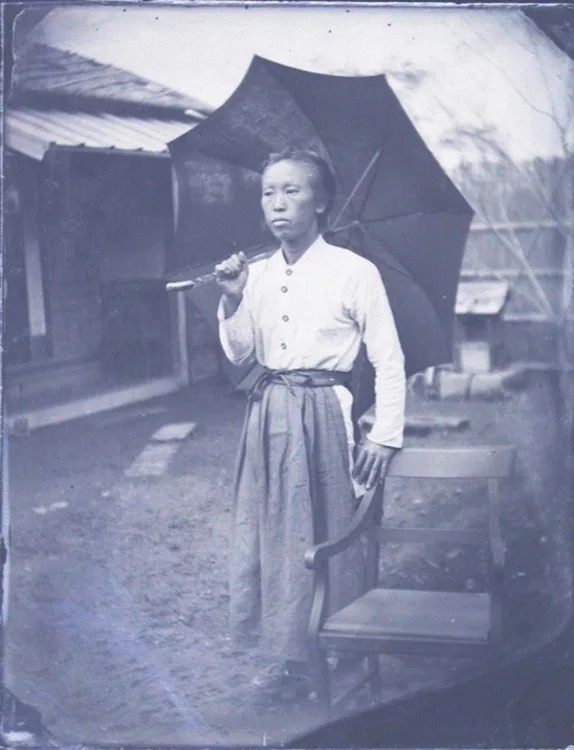

Ryū Shima was born in Kamihisakata village in the Yamada District of Kōzuke Province (now the Umeda neighbourhood of Kiryū City, Gunma Prefecture). She is known for being one of the first generation of Japanese women photographers and for the photograph of her husband, Kakoku Shima (1827–1870), entitled Kabocha o katsuide warau Shima Kakoku zō [Portrait of Kakoku Shima Carrying a Kabocha Squash and Laughing] (ca. 1860s).

R. Shima’s childhood name was Yone Okada, and she was later known as ‘Kaku’. On marrying she changed her name to Ryū. From the age of seven to thirteen she studied at the Shōseidō temple school, founded by Kajiko Tamura (1785–1862); in 1841 she went to Edo (now Tokyo) as a scribe for the Hitotsubashi Tokugawa clan. At around the age of thirty-three, it is said that R. Shima met her future husband, a native of Tochigi who had regular dealings with the Hitotsubashi Tokugawa as an eshi (master painter) and interpreter, and who was four years her junior. They married in 1855 and lived in various places, including within the northern neighbourhood of the Sensōji Temple at Asakusa and near the house for shogunate servants, which was located behind the residence of the Tachibana clan in Edo.

R. Shima’s husband learned oil painting and photography, which had been introduced from the West during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate and Meiji Restoration period, and made an active study of movable type printing production for publishing medical texts. At the same time, R. Shima also came into contact with Western cultural products like photographic art, and she took photography lessons from her husband. Kaichūki [A pocket diary], thought to have been written in 1870, records the names of the chemicals used in photography, as well as formulas, costs, instructions on the collodion wet plate process and other notes, offering a glimpse of R. Shima’s interest in photography.

In 1864 R. Shima took a photo portrait of her husband aged forty-two, writing ‘Photographer: Ryū Shima’ on the back and thereby naming herself as a photographer. She is said to have opened a photography studio in Kiryū City at some time after that, but the details are unclear. She is said to have photographed Sōun Tazaki (1815–1898), an Ashikaga retainer in her artistic circle in 1865; in about 1866 the foreign affairs magistrate Sukekuni Kawazu (1821–1873); and in about 1869 the Irish doctor William Willis (1837–1894). In each case, however, it is unclear whether she or her husband was the actual photographer.

Following her husband’s unexpected death in 1870, R. Shima returned to her hometown of Kiryū City in late 1871 with all of their personal effects. These materials, said to include approximately two thousand items, have been kept in the Shima family collection in the Umeda neighbourhood of Kiryū City for generations. The discovery in 1983 of this collection of personal effects presented an opportunity to make the activities of the Shimas known to a wider audience. Amongst this collection, researchers identified some 1,208 objects, including the aforementioned portrait of K. Shima (1864), as well as art works by associates of his – including Kazan Watanabe (1793–1841), Chinzan Tsubaki (1801–1854) and Ryūko Takaku (1810–1858) – and other objects owned by the couple, such as wet-plate photographic negatives on glass. These items were entrusted to the Gunma Prefectural Museum of History and designated in September 2009 as Important Cultural Properties of Gunma Prefecture. As of today, at least five wet-plate glass negatives taken by R. Shima in Kiryū City following her return have been identified.

Reappraisal of R. Shima’s work is currently under way, and her photographs have been featured in several group exhibitions, such as An Incomplete History: Women Photographers from Japan, 1864–1997 (Visual Studies Workshop, Rochester, New York, 26 June–8 August 1996), Kiryū no āteisuto daishūkakusai [Kiryū Artists’ Great Harvest Festival], Okawa Museum of Art, 7 October–3 December 2023) and I’m So Happy You Are Here: Japanese Women Photographers from the 1950s to Now (2024 Arles International Photography Festival, 1 July–29 September 2024).

Nevertheless, it is difficult to say whether it is appropriate to call her ‘the first woman photographer’. Although we can confirm that a considerable number of women worked in the photography studios opened by Gyokusen Ukai (1807–1887) and Renjō Shimooka (1823–1914) in around 1861 and 1862 respectively, research into Japanese women photographers of the period remains insufficient. As far as R. Shima is concerned, we must clarify the specifics of her activities as a photographer rather than draw conclusions solely from a signature that reads ‘photographer’ on the back of portrait. Viewed from this perspective, it is as yet too early to establish her position within the history of photography; hereafter, further and more in-depth research is to be expected.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Traces of the Future: Women Photographers from Japan”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2026