Sturtevant

Sturtevant: Drawings, 1988-1965, exh. cat., Bess Cutler, New York (22 October – 16 November 1988), New York, Bess Cutler, 1988

→Sturtevant: Drawing double reversal, exh. cat., Museum für Modern Kunst, Frankfurt (1 November 2014 – 1 February 2015) ; Albertina Wien, Vienne (14 February – 17 May 2015) ; Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin (30 May – 23 August 2015), Zurich, JRP/Ringier, 2014

→Surtevant Sturtevant, exh. cat., Museo d’Arte contemporanea Donnaregina, Naples (1 May – 21 September 2015), Milan, Electa, 2015

Elaine Sturtevant, Museum Für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, 25 September 2004 – 30 January 2005

→Sturtevant: double trouble, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 9 November 2014 – 22 February 2015 ; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, March – July 2015

American multimedia artist.

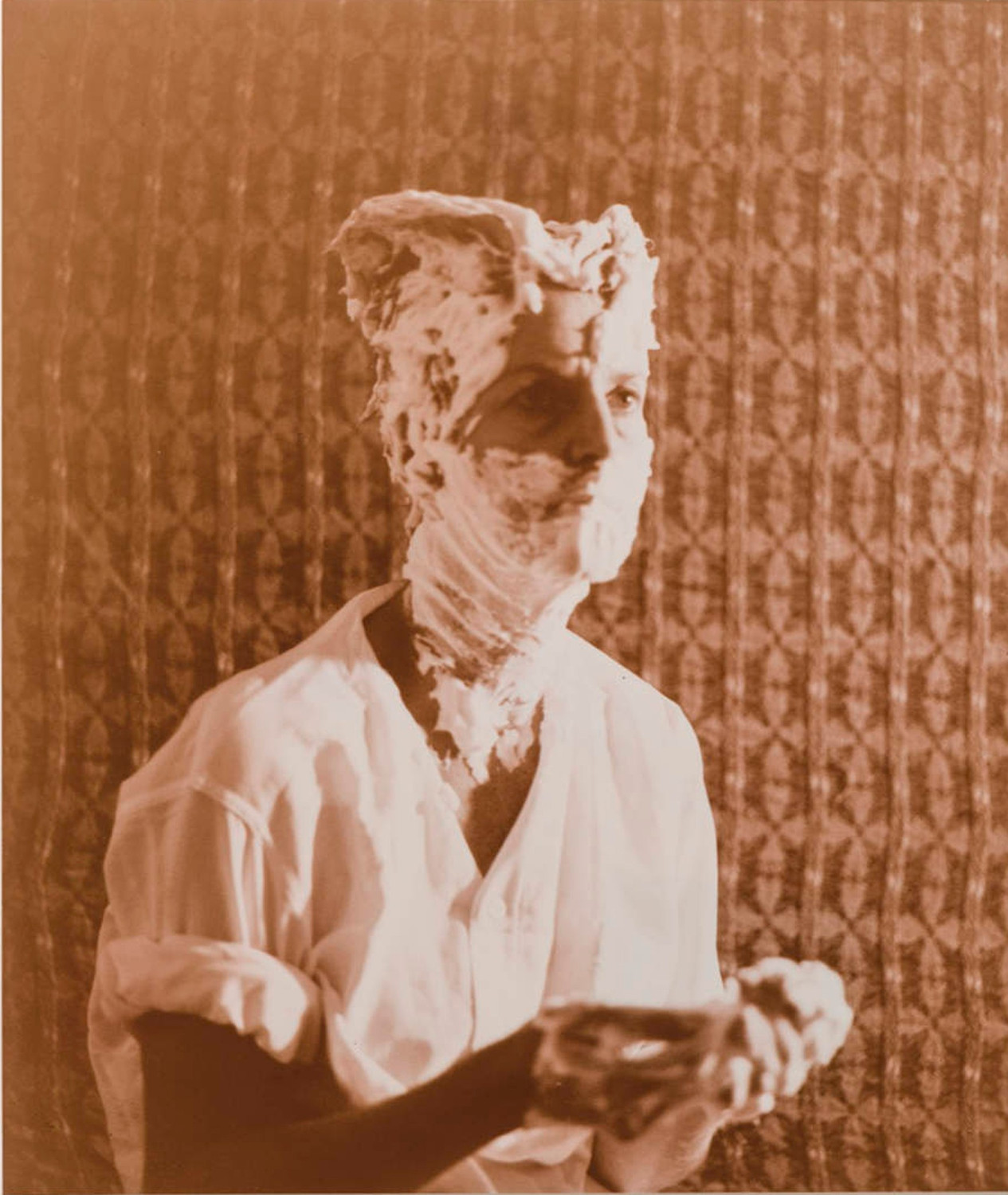

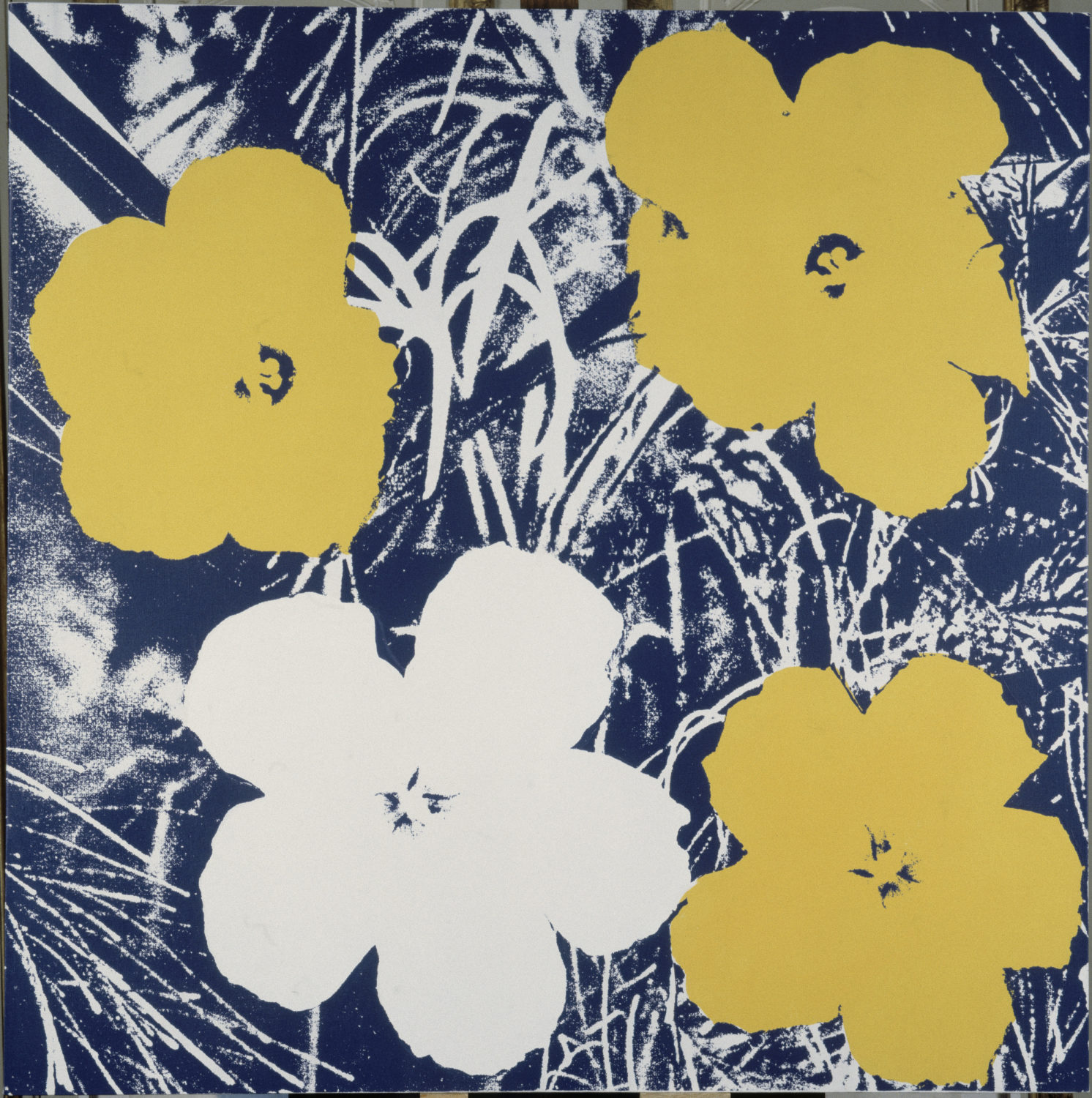

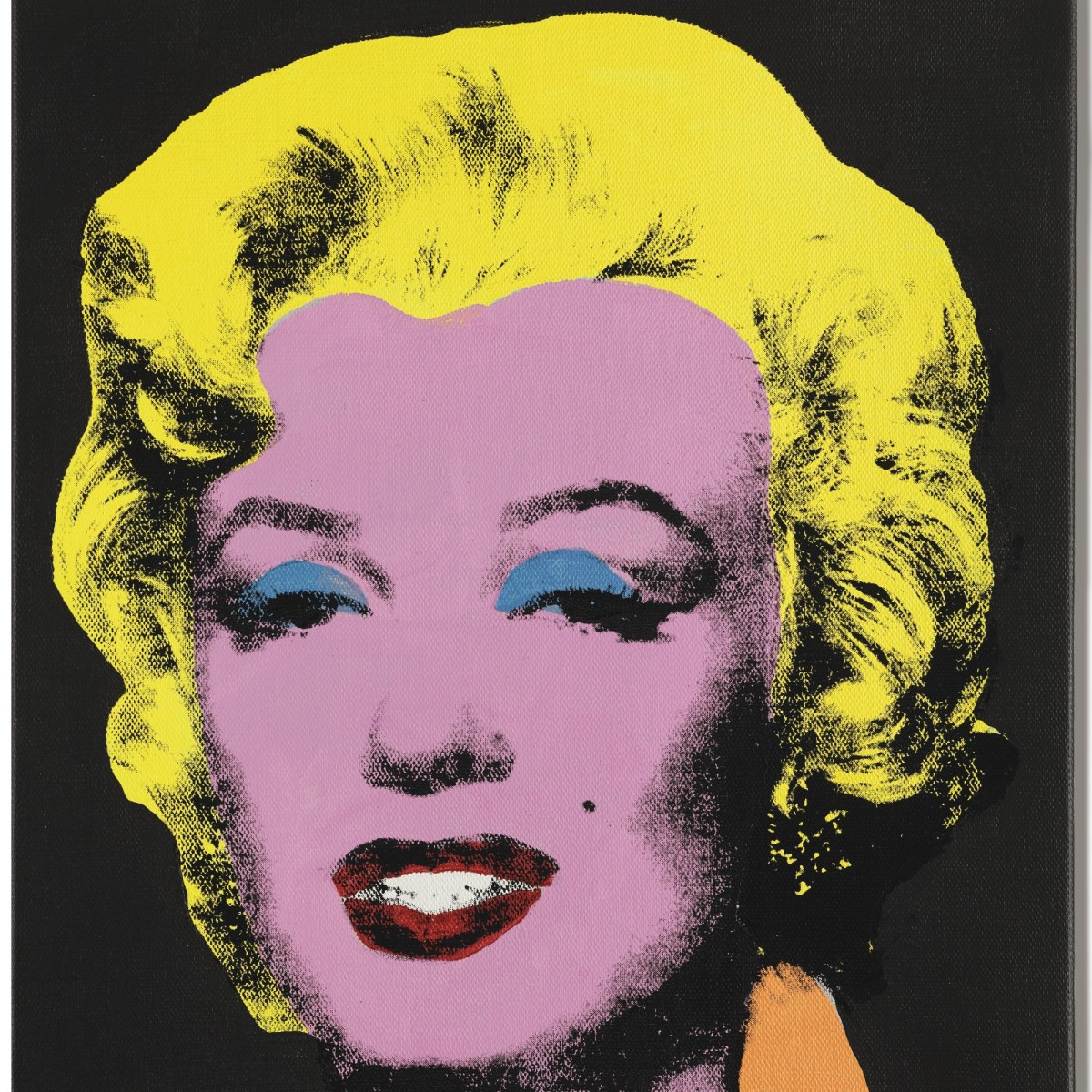

The work of Elaine Sturtevant, a landmark in the history of art, questions representation and reproduction. Since the beginning of her career almost fifty years ago, she has challenged the critical discourse and postmodern rhetoric, guidelines based on post-Duchampian diversion. Her large 2004 retrospective at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt was true to its title: The Brutal Truth, revealing that her work are not duplicates. She questioned the autonomy of art in a new way. From the early 1960s her work has consisted of replicating artworks by artists such as Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp, Joseph Beuys and Roy Lichtenstein, dating from just before they became recognised on the international scene, thus revealing a critical intuition and capacity to determine the trends of a history in the making. Her project is, at its origin, considered aggressive and provocative, not to mention unspeakable. Often mistakenly associated with the appropriationism of the 1980s, her work anticipated and radically stood out from the reproduction process of Sherrie Levine (1947) and the political undertaking of desacralization of Mike Bidlo and of Philip Taaffe. Distanced from these practices, she developed in parallel to the movement of historical thinking of Michel Foucault and Deleuzian philosophy.

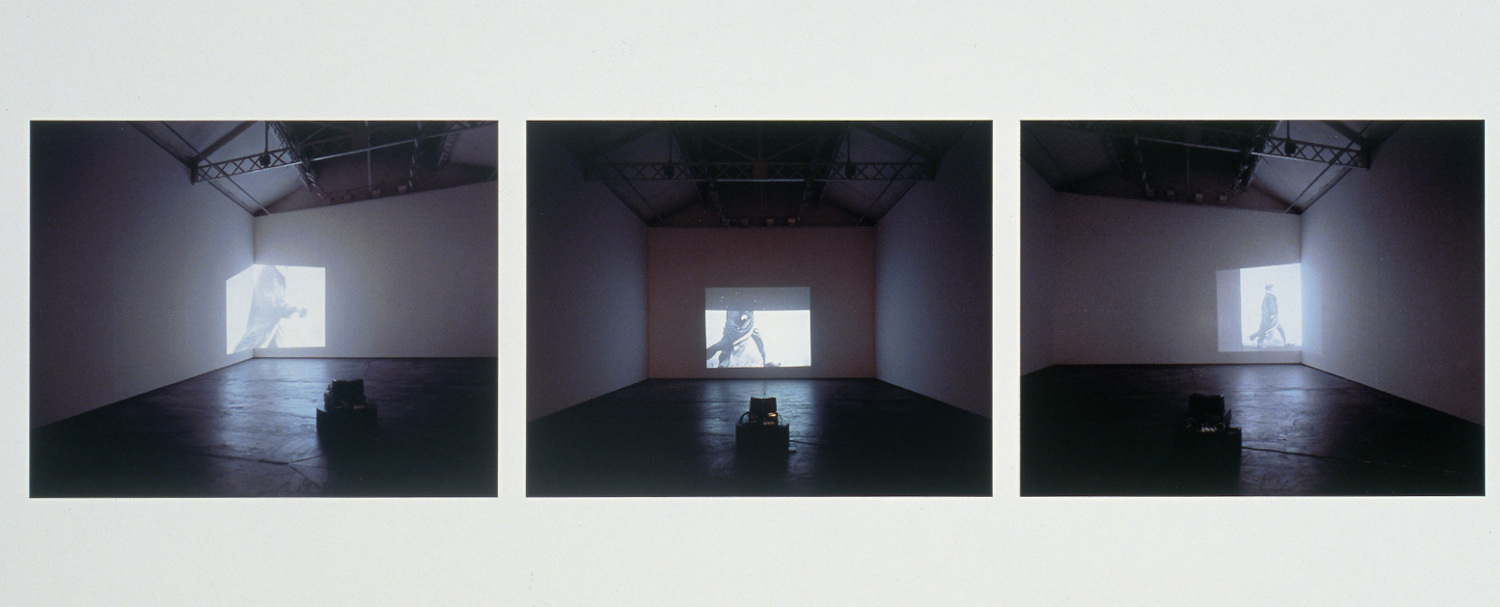

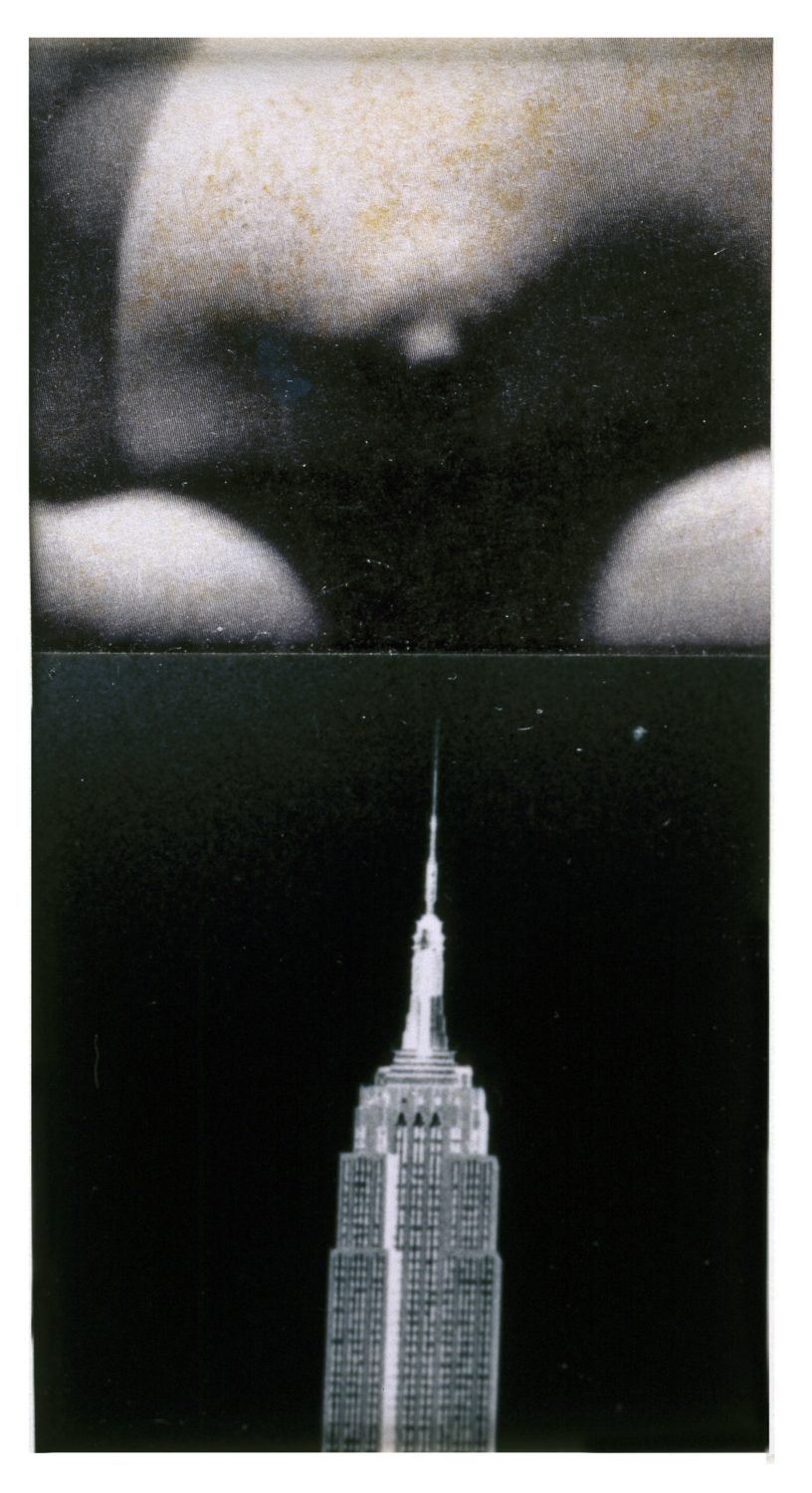

For several decades she has concentrated on the power of art and images, the idea of cloning, and in a visionary way, predicted the impact of cybernetics and the digital revolution, a revolution which was only the promise of false subversions and that ended in making the handmade replica technically obsolete to open the reign of the simulacrum and simultaneous diffusion. What interests her even more in this digital age is the reversal of values, hierarchies of reality and its representations. “My works reflect our cyber world of excess, limitations, transgression and dilapidation. Once, the higher power was the force of knowledge, intelligence and truth. Today, the superior power is to hate, to kill, while a mask of truth covers the dangerous power of lies,” she wrote in 2007. Two fundamental figures reappear constantly in her work: M. Duchamp and A. Warhol. If there is one thing accepted in art today, it is the possibility for an artist to carry out A. Warhol’s “programme”. Yet, E. Sturtevant is perhaps the only one to have integrated the true logic of things (to the detriment of the logic of meaning), that of the series, the surface, the machine. The circular projection Dillinger Running Series (2000) is one of the most remarkable examples; in the movement of walking it reveals the movement of the machine in the centre of the same space. Her videos are composed of looped sequences, where everything seems to be delivered in reality as the only event. The camera is no more part of the subject who is filming than it is of the object it is filming. It records the passage of a body and an object.

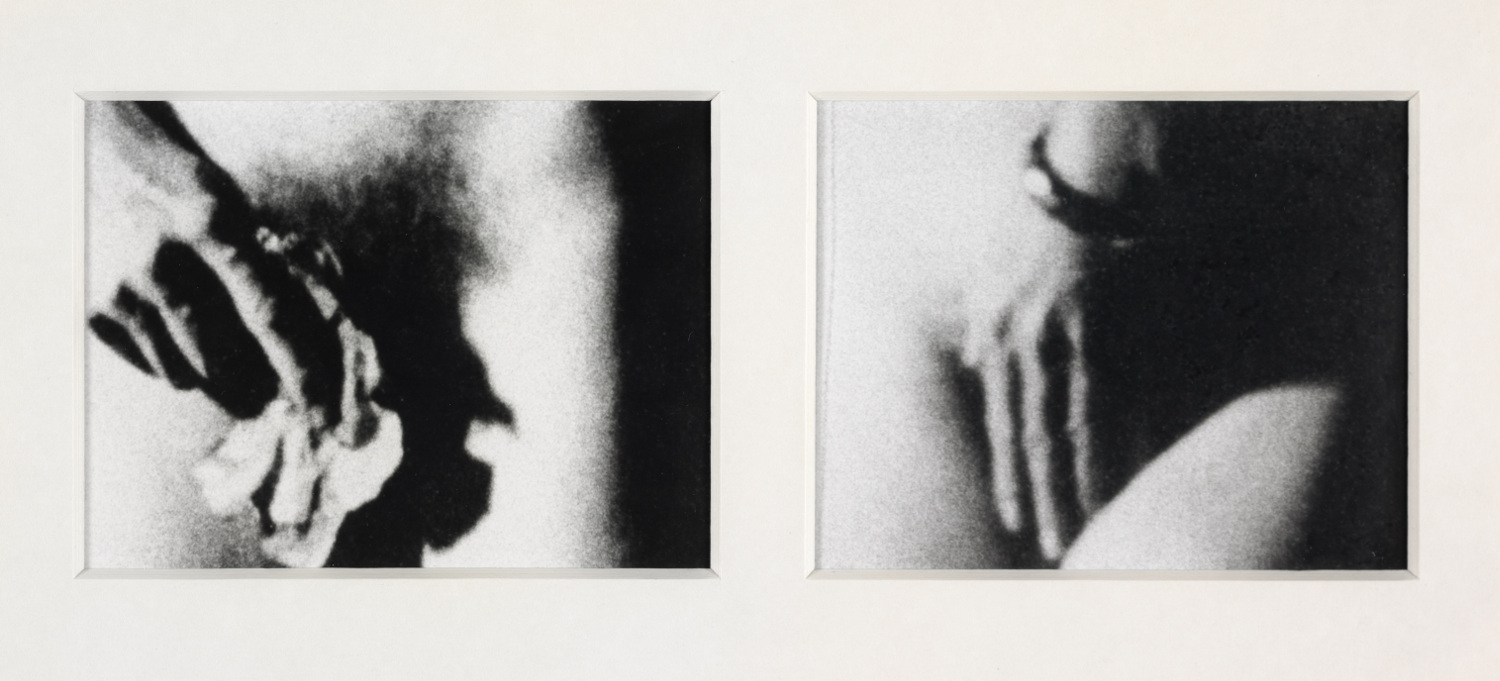

The film and video installations show to what extent this production from the last ten years exceeds and renews all questions of the origin: that of impulse, of seeing and of doing, mechanisms of clearing and repetition, and pornography, of course, which synthesises all the others. One of her most powerful installations, The Dark Threat of Absence/Fragmented and Sliced (2002), composed of seven screens arranged in a line distorts modes of interpretation and perception. It is not a reference to Paul McCarthy’s video The Painter, even less to painting, but rather the great, globalised factory of images: all of these images of mutilation, excess, disjunction, transgression, fear and depletion that remain static and flash on the screens. From this principle of fragmentation, the artist prevents the adhesion, suspends enjoyment, the door to the limits of frustration, of a form of violence in language, because language clearly holds a determining place here that opposes the background noise and resists with all its “biopower” to inertia.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2020

Elaine Sturtevant - Talk

Elaine Sturtevant - Talk