Research

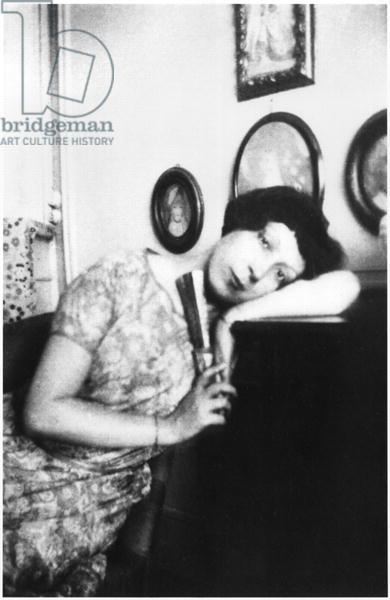

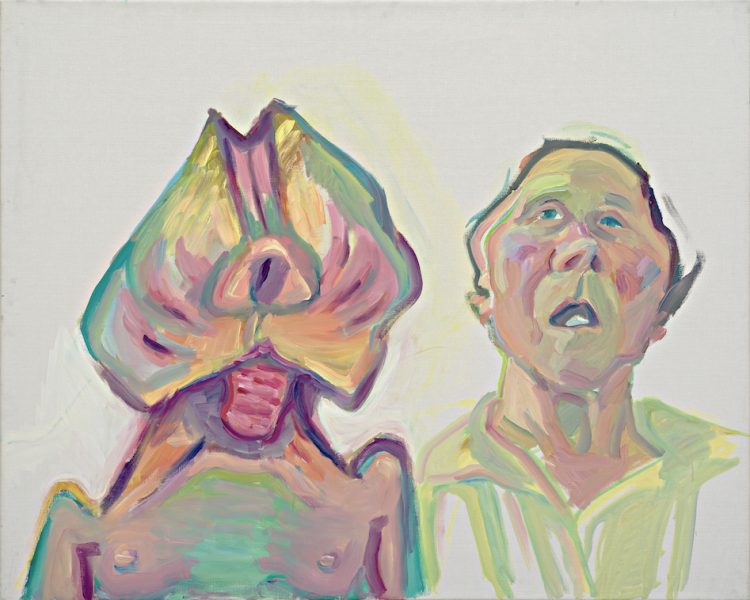

Lotte Laserstein, In meinem Atelier [In My Studio], 1928, oil on canvas, 46 x 73 cm, Collection Michal and Renata Hornstein, Montréal

Over the course of the first decades of the 20th century, women painters, notably in Europe, were to modify the imaginary connected to the self-portrait by relying – not without a degree of modernity – on the otherness of their experiences: those of maternity, of a new womanliness and of sorority, among others. All of these themes would later be picked up and extended by feminist artists starting in the 1960s–1970s. I will focus on a few of these typologies here.

Male Self-portrait, Female Self-portrait

The self-portrait was constituted as an autonomous genre in the 16th century, owing to three fundamental trends: the growing popularity of mirrors, the social development of a new awareness of the self, and the changing status of artists, shifting from artisans to artists.1 During the following centuries, the concepts of genius, power, and masculinity would endlessly fuel the myth of an art form animated by a virile and sexual energy.

Beginning in the Renaissance, women favoured the “self-portrait as artist” – a subversion in itself – as a means of affirming their artistic ability, as was for instance the case of Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1535–1625) who represented herself painting a Virgin with Child (1556). However, commentators, until the end of the classical age, were especially quick to mention beauty as the primary quality of the female painter,2 and collectors and patrons, thus becoming infatuated with the female self-portrait, saw in her a “marvel of nature”.3

During the 19th century, the liberalisation of the art market and the birth of modernity had a major influence on male self-portraiture in Europe. The ideal of the Ancien Régime – the artist as aristocrat or grand bourgeois – was replaced, following the French Revolution of 1789, by the republican yet still elitist version of the author who was both worthy and unique.4 New figures of marginality emerged (bohemians, visionaries, and martyrs), but these were still based on the virile values inherited from the Renaissance.

In the same period, the position of women remained complicated.5 Despite some advances, including their progressive entry into art schools (in 1873 the Académie Julian; in 1900, the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, in France alone), the affirmation of the status of artist required defiance of many conventions. This particularity called, within the context of self-portraiture, for responses inevitably different from those provided by men: the marginality of women, very different from the marginality displayed at the time by their male counterparts, led them to invent innovative iconographies.

Paula Modersohn-Becker, Autoportrait au sixième anniversaire de mariage, 1906, tempera on cardboard, 101.8 x 70.2 cm, Museen Böttcherstrasse, Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Brême, © Paula-Modersohn-Becker-Stiftung, Brême

Self-portrait as Mother

Maternity is by definition particular to women. In self-portraits, it took two main forms: the less common of these was pregnancy and the more common was the representation of the artist’s bonds with her children. While several gravid Biblical figures populate religious painting, the first among whom is the Virgin Mary, rare are the pregnant women who form the subject of a pre-1960s portrait. This was due to the many social taboos surrounding pregnancy, deemed immodest since it constitutes the manifest sign of sexual activity, as well as the superstitions pertaining to the health of the foetus.6 These constituted formidable barriers for those wishing to establish their own image in this way.

One of the first women painters to venture into the realm of self-portraiture was German painter Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907). Once known only to a small group of admirers, including Rainer Maria Rilke, who greatly appreciated her, she finally gained recognition more than a century after her premature death linked to childbirth. One of her most famous paintings is Selbstbildnis am 6. Hochzeitstag [Self-portrait on Sixth Wedding Anniversary], in which she appeared partially unclothed (a first for someone of her sex7) and pregnant. However, there was no biographical realism here – at this date, she was not yet expecting a child – rather the programmatic utterance of her deepest desires, in which the desire to create and to procreate were closely intertwined.

Elsa Haensgen-Dingkuhn, Selbstbildnis mit Sohn im Atelier [Self-portrait with her son in the studio], 1928, oil on board, 73 x 61 cm, © Elsa Haensgen-Dingkuhn, © Photo: AKG Images

While maternity has long been considered one of the causes of women distancing themselves from culture, deemed the ultimate masculine domain – there would be much to say on the rarity of the self-portrait as father – the history of the representation of the artist as mother is marked by self-portraits with Rousseauist accents by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755–1842) painted at the time of the invention of maternal love by the philosophers of the Enlightenment. A century later, the stakes changed: it was now a question of women casting a critical gaze on the difficulties of combining career and maternity. Thus Hanna Nagel (1907–1975), an artist and illustrator close to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity, a movement recognised for its acerbic examination of society under the Weimar Republic), featured herself as a mother on several occasions, notably in Das Kleinkindersystem! Die Künstlerin als erschöpfte Mutter beim Kartoffelschälen, umgeben von ihren zahlreichen Kindern [The system of young children! The artist as exhausted mother peeling potatoes, surrounded by her children, 1931]. In this drawing, she highlighted the alienation that maternity can produce, about which – similar to P. Modersohn-Becker in her aforementioned painting – she was yet to have had any personal experience (her daughter was born in 1938). This porosity between professional and family life experienced daily by so many women also shows through in the work of another German artist, one of the first to be admitted to the Kunsthochschule in Hamburg, Elsa Haensgen-Dingkuhn (1898–1991), after the birth of her son Jochen (Selbstbildnis mit Sohn im Atelier, [Self-portrait with her son in the studio],1928): this time in an autobiographical mode, she represented herself in the studio with the child in her arms.

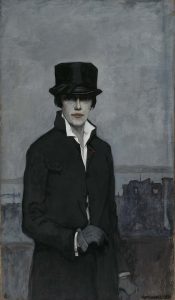

Romaine Brooks, Autoportrait, 1923, oil on canvas, 117.5 cm x 68.3 cm, 46 1/4 x 26 7/8 in., Smithsonian American Art Museum

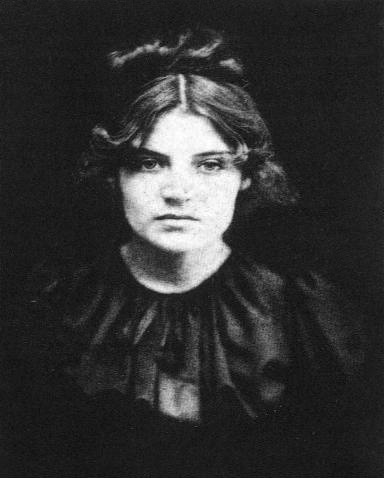

Lotte Laserstein, Selbstporträt mit Katze [Self-portrait with Cat], 1928, oil on board, 61 x 51 cm, Leicester, New Walk Museum & Art Gallery

Self-portrait as “New Woman”

Just after the First World War, when the millions of dead at the front required in each belligerent country that the women take charge of aspects of society formerly reserved for men, a “new woman” was to emerge in novels, on the stage, and in the pages of magazines – a woman who was sporty, liberated, and androgynous, whose short hairstyle was soon to become her most recognisable attribute. While the representation of the independent woman as a “garçonne” was highly contingent – given the extent to which its reality remained fragile and limited – its style was widely adopted by “modern”8 artists. It became a way of thinking about the stereotypes surrounding femininity. It was also a way of escaping certain social assertions and laying claim to freedom of body and mind. After Romaine Brooks (1874–1970), for whom, from the early 1910s, androgyny, homosexuality, and self-portraiture were deeply entwined (At the Seaside – Self-Portrait, 1912), Lotte Laserstein (1898–1993) represented herself many times as a “new woman” (Selbstporträt im Atelier Friedrichsruher Straße [Self-portrait in the Studio on Friedrichsruher Straße], c. 1927). Like R. Brooks before her, she was the author of female portraits in which her models escaped reification. While her aesthetic – a rather academic naturalism – did not have the radicality of some works by her contemporaries, it was nevertheless in the service of a transformed view of femininity. In her Selbstporträt mit Katze [Self-portrait with Cat, 1928], she presents herself as she paints, with very short hair, wearing a shirt cut in masculine lines, professional and self-possessed, stripped of any ordinarily feminine characteristic. In the background, the urban landscape unfolds into the distance; this and the cat, the symbol of independence, form the two other characters of the painting. It is in this same framework of the studio that certain artists were to invent a new iconography: that of sorority.

Sororities

For men artists, representing themselves alongside a female model, as the tradition had been developed since the 19th century, provided the opportunity to present otherness. The studio – the marginal place par excellence in the bourgeois imagination – frequently served as a set for staging domination and sex. Under the brush of the woman painter, this type of self-portraiture often supports the construction of a different image of the body than the one conveyed by art, but also mass culture, and a different relationship to the model, liberated of the sense of possession: “Women are depicted in a quite different way from men,” recalls John Berger, “not because the feminine is different from the masculine – but because the ‘ideal’ spectator is always assumed to be male and the image of the woman is designed to flatter him.”9 In this respect, it is striking to note the extent to which the search for canonical beauty does not seem to preoccupy most women artists. However, particular attention to the creation of a balanced relationship among the protagonists was evident in the elaboration of a new repertoire of gestures, positions of the body, and interplays of the gaze, as well as in the care taken over certain details of the body.

Charlotte Berend-Corinth, Selbstbildnis mit Modell [Self-portrait with Cat], 1931, oil on canvas, 90 x 70,5 cm, Berlin, Nationalgalerie, © BPK, Nationalgalerie, SMB © Photo: Jörg P. Anders

For In meinem Atelier [In My Studio, 1928], L. Laserstein chose to represent herself alongside her friend Gertrude Rose, known as Traute. In it, she celebrates both the androgyny of her companion and her own, and the naked body of Traute is depicted with unusual realism (athletic lines, precisely drawn pubic hair, breasts flattened by her prostrate position, and bluish veins under the skin). In another painting – Ich und mein Modell [My Model and I, 1929–1930] – she insists more on their tender and respectful attachment and on their egalitarian relationship.

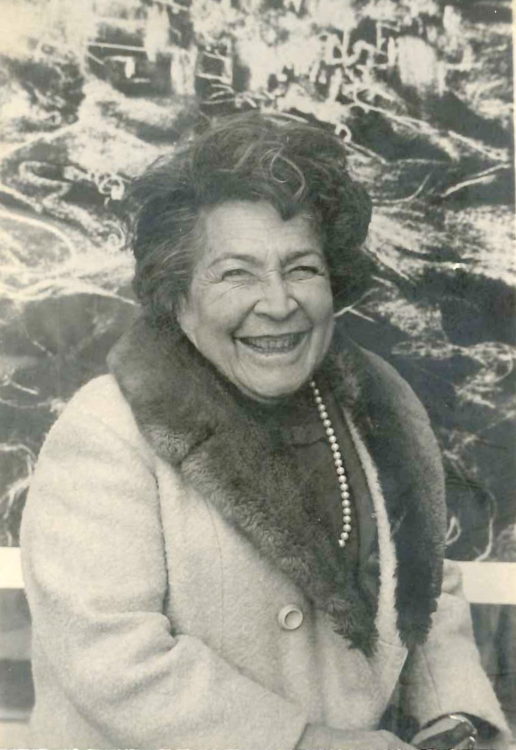

In this register, the case of Charlotte Berend-Corinth (1880–1967) is particularly interesting. A future member of the Berlin Secession, she posed half-naked with her teacher and soon-to-be husband, Lovis Corinth, in a dual portrait with a highly charged erotic atmosphere painted by the latter in 1902 (Selbstdnis mit Charlotte [Self-portrait with Charlotte]). At the end of a meal, he theatrically grabs one of her nipples in one hand and makes a toast (intended for the viewer?). When, twenty-nine years later, C. Berend-Corinth represented herself alongside a naked woman, the choice of poses and expressions conveys a very different atmosphere, in which the model, as pretty as she is, plays a very different role in the construction of the painting, attesting to her supportive, sisterly role alongside the artist (Selbstbildnis mit Modell [Self-portrait with Model, 1931]). These paintings strangely echo a pioneering self-portrait by Suzanne Valadon (1865–1938), with André Utter, Adam and Eve (1909), in which she seeks a relationship of equality between the figures while expressing her desire for the body of the lover.

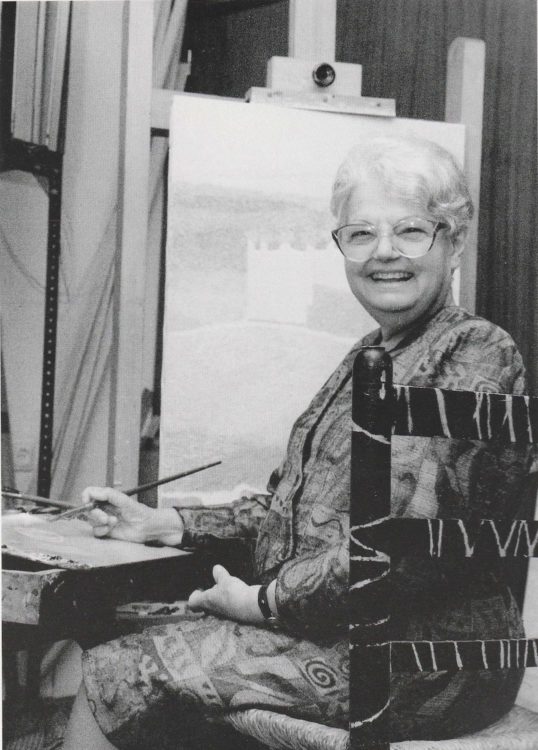

These few pathways studied by women artists in the early 20th century have enabled them to appropriate in a new way a genre that had up until then been very widely dominated by the mythology of the male. They paved the way for upcoming generations, such as Sylvia Sleigh (1916–2010) or Joan Semmel (born in 1932), who, from the 1960s–1970s, undertook to transform the painted self-portrait into the locus of their struggle to present a less normative view of women and their relationship to the world, and to escape the marginality to which art history had long condemned them.

Camille Viéville holds a doctorate in contemporary art history and is an independent researcher. An expert in 20th century portraiture, she is the author of several books (Balthus et le portrait, Paris, Flammarion, 2011; Le Portrait nu, Paris, Arkhê, 2017; Les femmes artistes sont dangereuses, co-written with Laure Adler, Paris, Flammarion, 2018), as well as numerous articles, some of which are dedicated to women artists (“Genres détournés. Le portrait nu dans la peinture féministe des années 1960-1970”, Corridor, n° 3 spécial: Réalisme et Gender dans la peinture du vingtième siècle, 2009; “Le détournement comme dénonciation dans l’art féministe des années 1960 et du début des années 1970”, Figures de l’art. Revue d’études esthétiques, n° 23 spécial: L’Image recyclée, 2013). She has collaborated with AWARE Magazine since 2017.

Kris Ernst and Kurz Otto, Legend, Myth, and Magic in the Image of the Artist. A Historical Experiment, preface by Ernst Hans Gombrich, New Haven, London, Yale University Press, 1979, p. 42–49.

2

Lacas Martine, Des femmes peintres du XVe à l’aube du XIXe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2015, p. 50.

3

Ibid., p. 79.

4

Heinich Nathalie, L’Élite artiste. Excellence et singularité en régime démocratique [2005], Paris, Gallimard, collection “Folio essais”, 2018, p. 323.

5

Morineau Camille, Artistes femmes, de 1905 à nos jours, Paris, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2010, p. 10.

6

On this subject, see Berthiaud Emmanuelle, Enceinte. Une histoire de la grossesse entre art et société, Paris, Éditions de La Martinière, 2013.

7

On the question of the nude self-portrait, I take the liberty of referring you to my book: Camille Viéville, Le Portrait nu, Paris, Arkhê, 2017.

8

Meskimmon Marsha, The Art of Reflection. Women Artists’ Self-Portraiture in the Twentieth Century, New York, Columbia University Press, 1996, p. 129.

9

Berger John, Ways of Seeing, London, Penguin, 1972, p. 64.

Camille Viéville, "New Pathways, New Voices. Women Painters and Self-Portraiture in Early 20th Century Europe." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/voies-nouvelles-nouvelles-voix-les-femmes-peintres-et-lautoportrait-au-debut-du-xxe-siecle-en-europe/. Accessed 12 July 2025