Wang Gongyi

Voigt Eberhard, « Wang, Gongyi », in Beyer Andreas, Savoy Bénédicte and Tegethoff Wolf, Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon : Die Bildenden Künstler aller Zeiten [General Artist Lexicon: the Visual Artists of all Times and Peoples] , Berlin, Boston, Walter de Gruyter, vol. 114, 2022

→Wang Gongyi : encres situations, exh. cat., Cité du Livre, Aix-en-Provence [9 février – 5 mars 1994], Institut Français, Tétouan [1994], Aix-en-Provence, Cité du livre, 1994

Wang Gongyi, Galerie du monde, Hong Kong, April 13 – June 4, 2022

→Multitudes, Chambers Fine Art, New York, May 6 – June 18, 2021

→Winsor Blue, Chambers Fine Art, New York, November 17, 2018 – January 19, 2019

Chinese visual artist.

Wang Gongyi (王公懿) lives and works in the United States, in Portland, Oregon. Despite her turbulent early years during the Cultural Revolution, when, like many young people, she was sent to the countryside to work, Wang Gongyi later went on to study at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in 1962. After graduating, she worked for a time as an editor at a fine Art publisher in Tianjin. Wang was accepted in 1978 to train in the Printmaking Department of the then Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, Hangzhou. After she graduated with her master’s degree two years later, she remained at the academy to teach. She began her long career as an artist after gaining recognition as the first woman to be awarded first prize at the 2nd China Youth Fine Art Exhibition, for her series of black and white woodcut prints, Qiu Jin, an homage to the 19th-century Chinese revolutionary heroine and martyr. Housed in the Museum of Contemporary Art at the China Art Academy, Hangzhou, it is lauded as a significant work by Wang, highly acclaimed in terms of the subject matter and for purporting to be a call for social reform and revolution.

Wang Gongyi’s print from this series, Establishing a Revolutionary Party, was part of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum’s exhibition, From Palace to Studio: Chinese Women Artists 1900 to the Present (2015). Her woodcut paintings have been described as being influenced by German Expressionism and Japanese woodcuts. Yet her inspiration may equally have its roots in the tradition of Chinese folk art while forming part of a more radical approach to ink painting that a number of artists began experimenting with in the 1980s.

In 1986 the French Ministry of Culture invited Wang to participate in an international cultural exchange program. This led to a revelatory and emotional experience, from visits to the Louvre, to her exhibiting and studying new printing techniques, including lithography, in both Lyon and Aix-en-Provence.

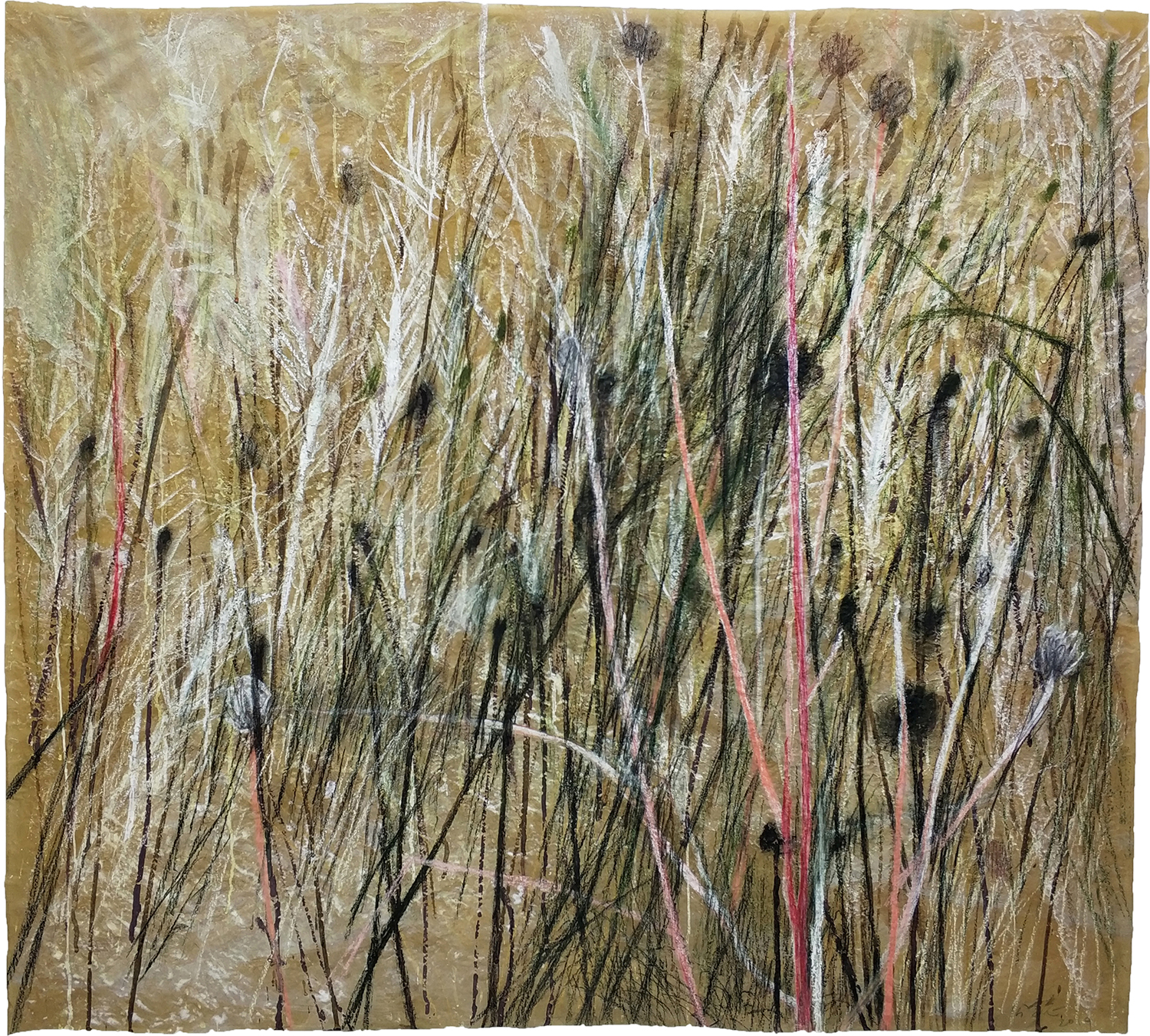

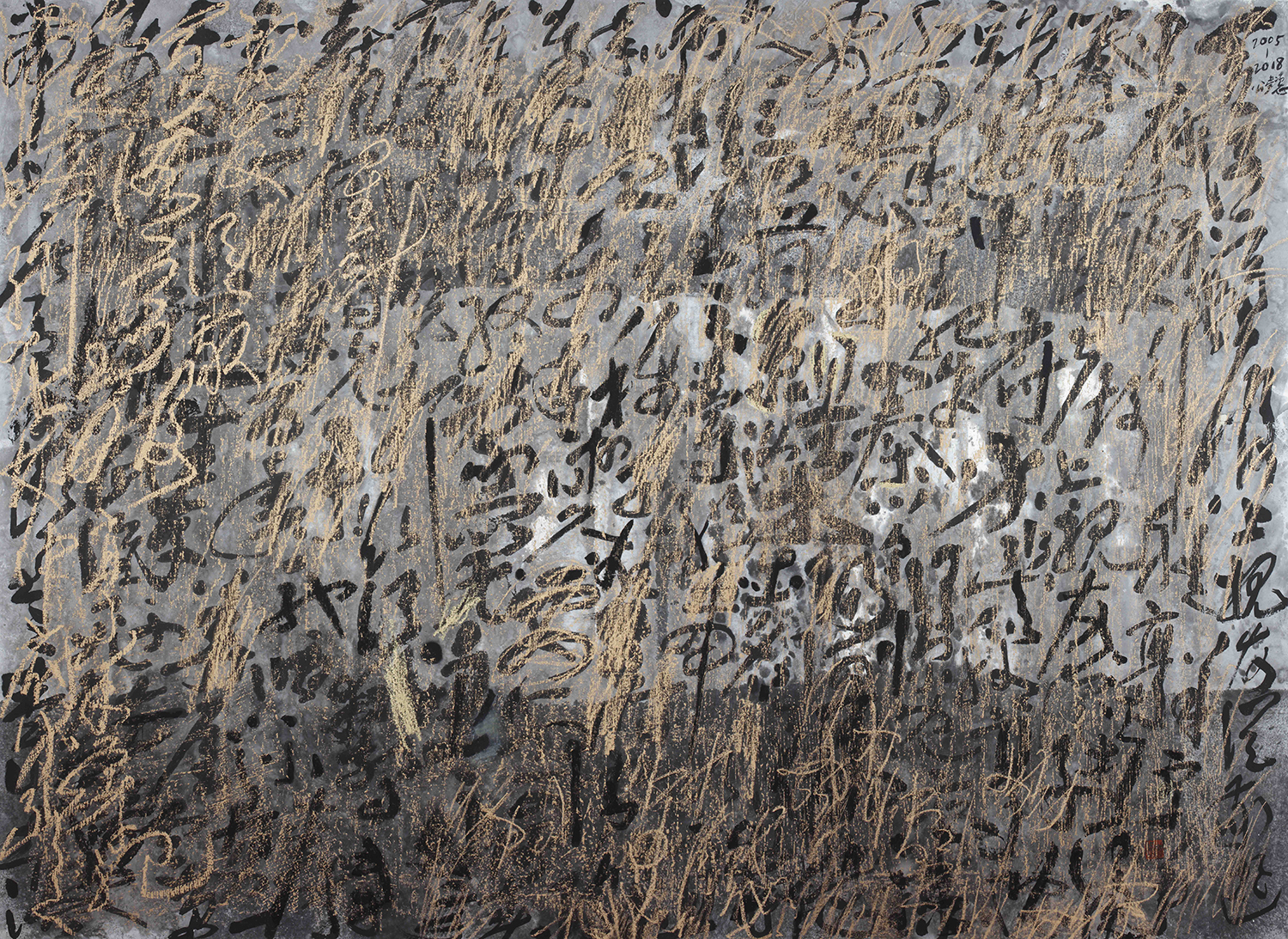

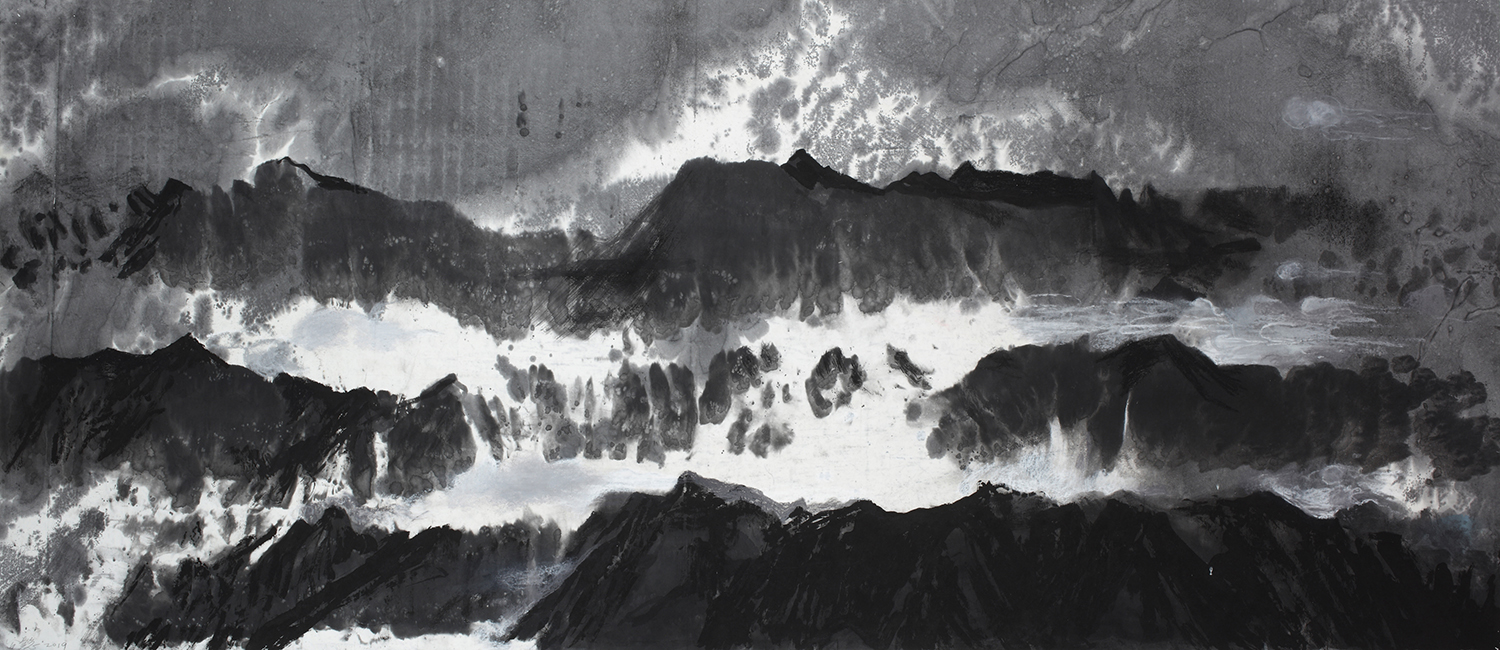

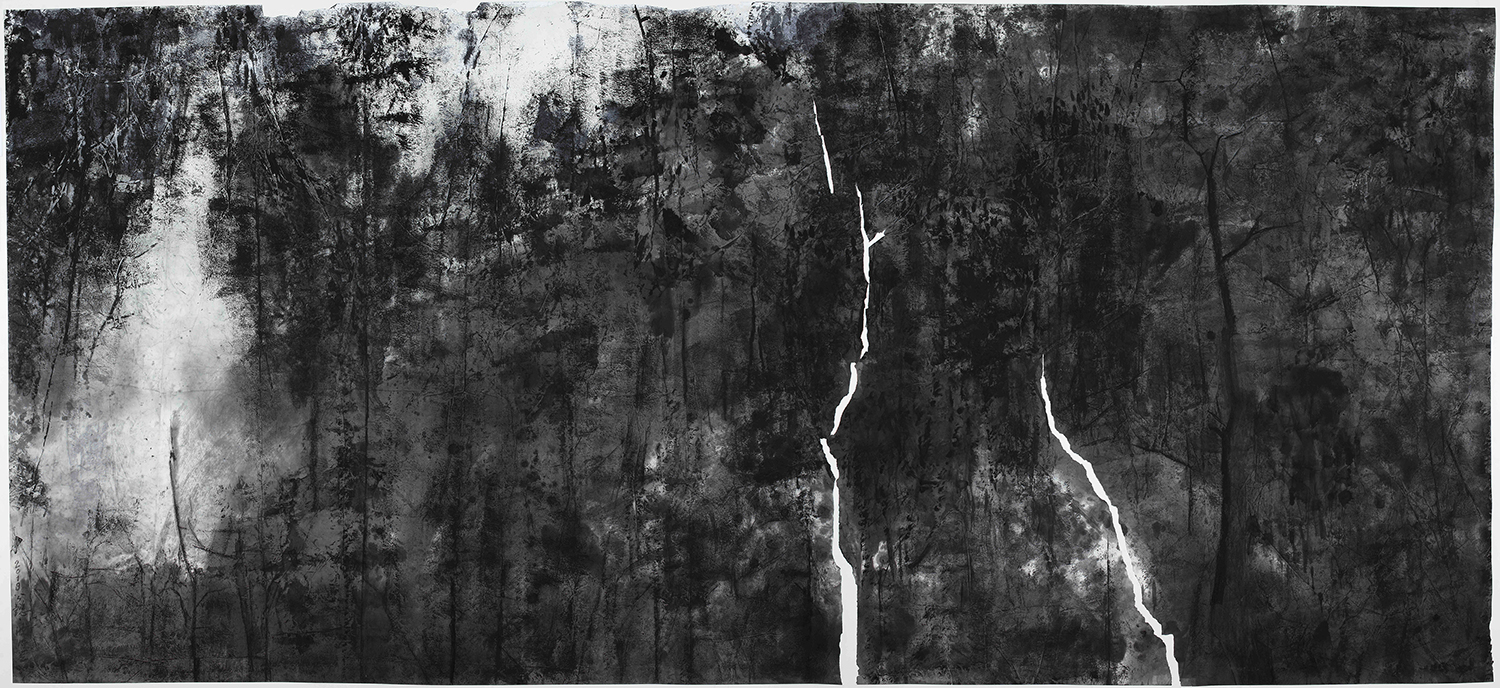

Wang also got her first glimpse of life outside of China, and was, ironically exposed to various figures in Chinese literature and the arts, missing as a result of censorship during the Cultural Revolution. This led Wang to explore a fresh, more experimental approach to her artistic practice, including new techniques and art installations: most notably, her ink on paper project titled, Listen, Look, Taste, Smell, But Do Not Ask (1993), which incorporated Chinese words and phrases asking “Why?” and “Do you understand?” These calligraphic-like words were intermittently overwritten by other words, resembling a palimpsest where in some instances, the words become illegible. Her gestures and brushstrokes became looser and freer, including a widening choice of subjects; scenes of rivers and the sea, mountain terrains and a shift towards natural forms – flora and various birds, acknowledging her spiritual affinity with nature.

In 1998 the conch shell was the subject of 140 brush and ink paintings, one made each day. As one of the eight auspicious symbols in Buddhism, the shell is often associated with spiritual awakening, introspection, truthfulness and strength. This association profoundly inspired Wang both in her approach to her work and to meditation, a practice she began in the 1980s, and which found her coming to a new level of understanding for and appreciation of her craft; titles of later paintings include Mantra (2012) and Blessing (2015).

Wang Gongyi participated in an acclaimed all-female exhibition in 1998, Half of the Sky: Contemporary Chinese Women Artists, organised at the Frauen Museum, Bonn, Germany. Wang later took up artist-in-residencies in Oregon Museum of Art before teaching at the Pacific Northwest College of Art. After her return to China from the United States, Wang worked in the Department of Printmaking at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, from 1992, before returning permanently to the United States in 2001.

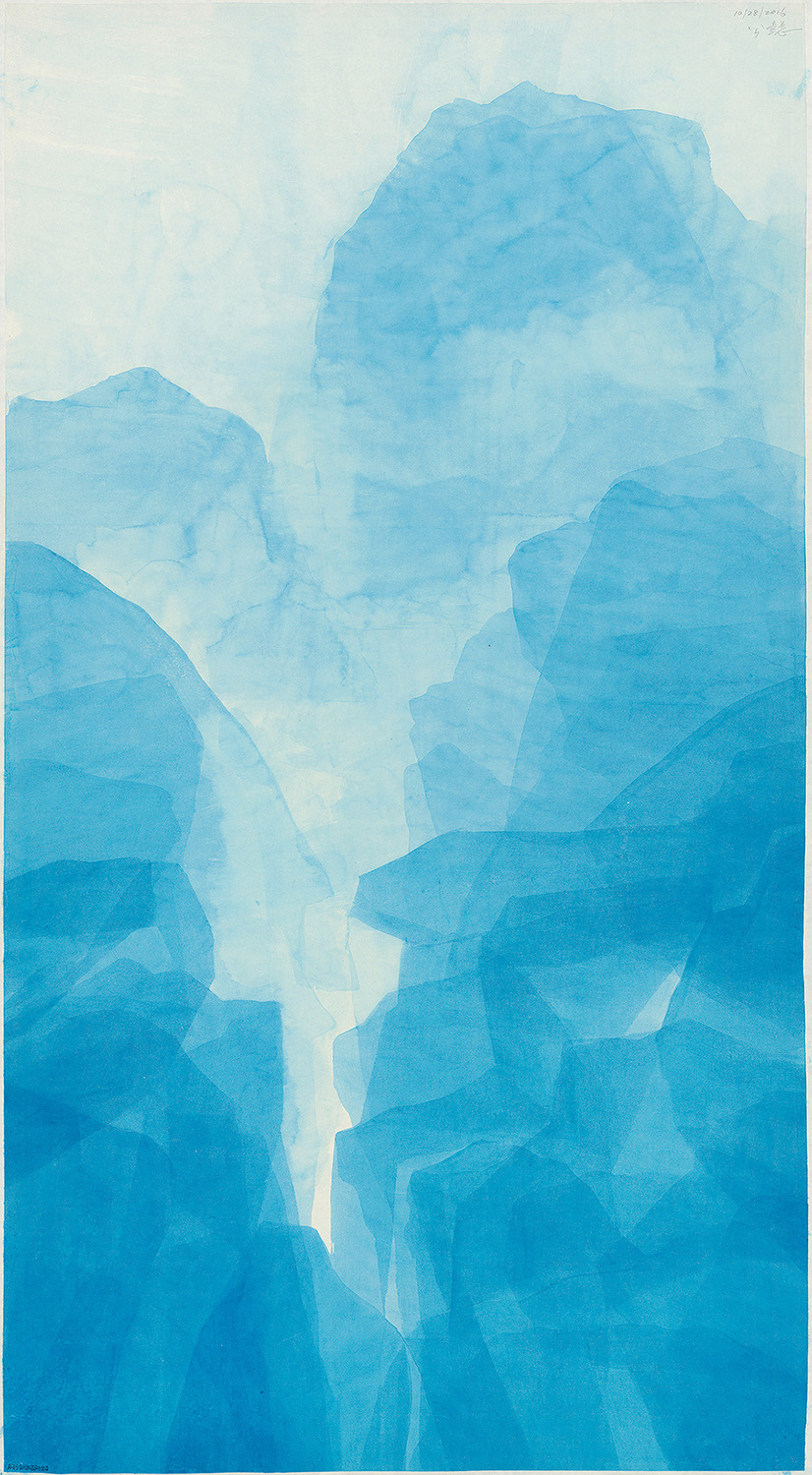

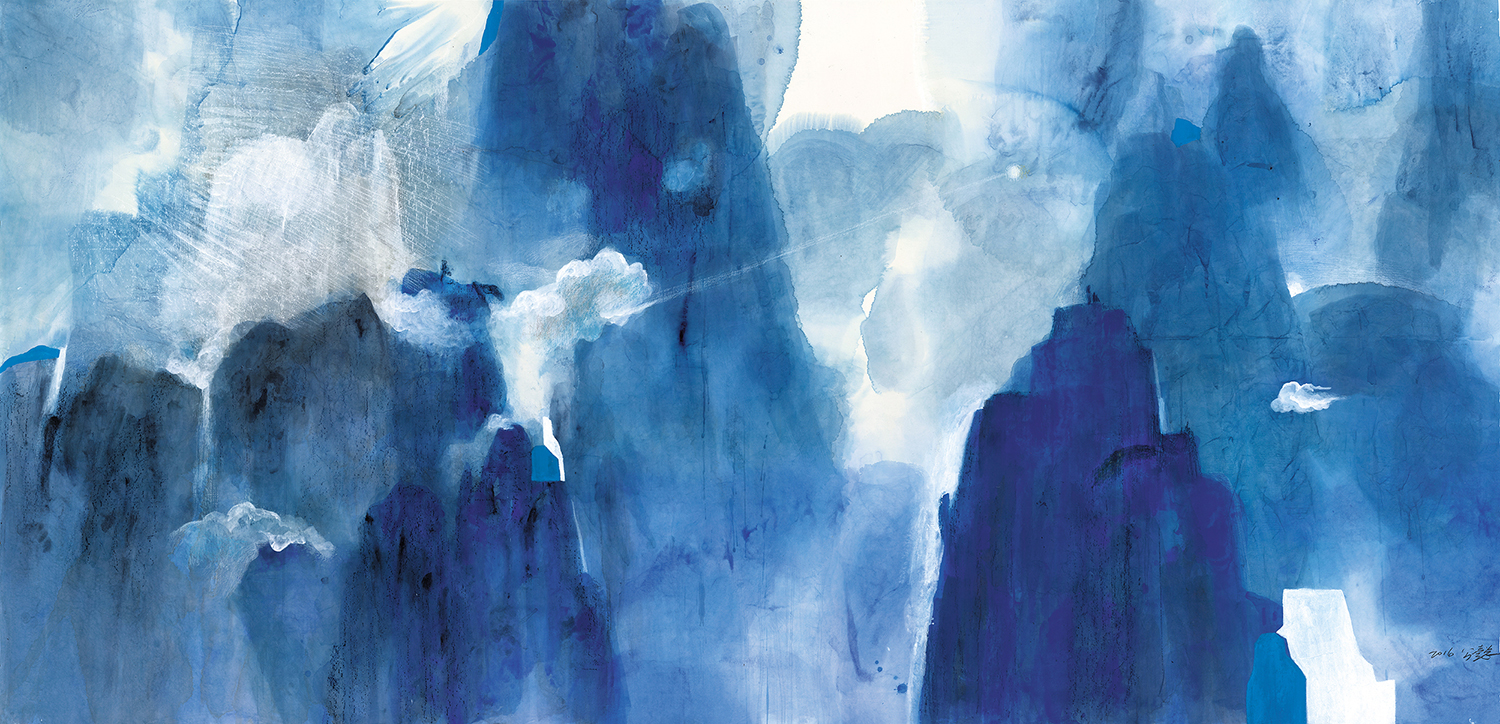

Since that time Wang has exhibited widely and continues to use layers of watercolour wash to create vast, atmospheric landscapes on panels. An approach that could be perceived as a modern interpretation of the shanshui (mountain and water) style of traditional Chinese landscape paintings. These are often inspired by her memories of the striking West Lake in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province.

Wang is particularly drawn to Winsor & Newton’s intense watercolour Winsor Blue, which she meticulously applies to create various densities of blue tones, layering the wash directly on traditional Xuan paper. This recent body of paintings led to her first solo exhibition in New York, Wang Gongyi: Winsor Blue (2018). Wang Gongyi has participated in the 2020 Taipei Biennial.

Interview with Wang Gongyi on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s | Asia Art Archive

Interview with Wang Gongyi on Chinese contemporary art in the 1980s | Asia Art Archive