Research

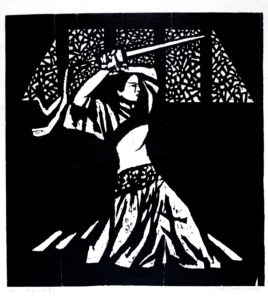

Jiang Caiping, Qiu Jin, 1992, ink on paper, 290 x 290 cm, National Art Museum of China (NAMOC), © Right reserved

As the People’s Republic of China celebrated its 70th anniversary, the cult of President Xi Jinping and the prevalence of virility now reflect the norms of a gendered system, reducing women to the status of wives and mothers. It is enough to simply look at Chinese military propaganda or the government’s current criticism of effeminate boys: the virile man is exalted, and his wife awaits his return. Is this a recent phenomenon? How did the representation of women in China evolve over the course of the twentieth century through the visual arts? And finally, to what extent have women artists participated in local feminist movements?

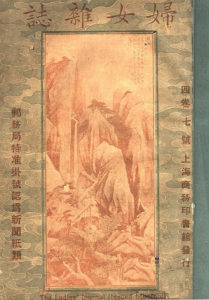

Wu Shujuan, Le Mont Wuyi, cover page of the newspaper Funü zazhi, no. 9, 1918, Institut des études chinoises, University of Heidelberg, © Right reserved

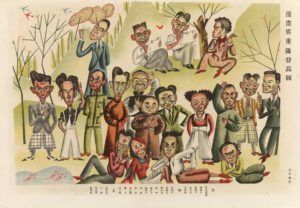

Wang Zimei, The Cartoon Circle Climbs the Mountains for Double-Ninth, 1936, paper, 37.50 x 26 cm, © British Museum

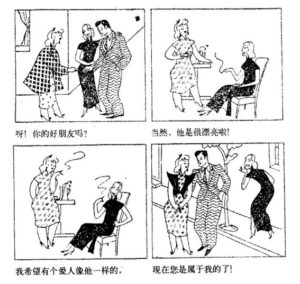

Liang Baibo (with Ye Qianyu), extract from Miss Bee, 1935, © Right reserved

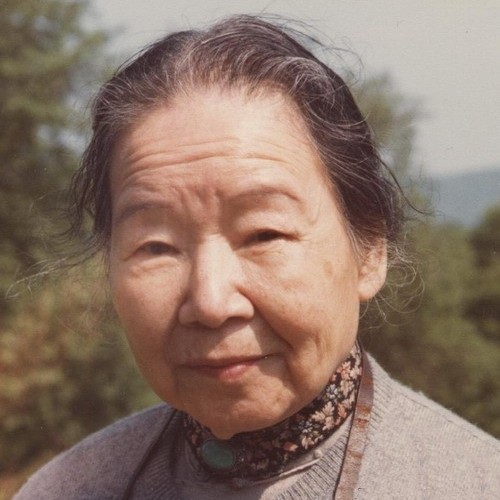

Although female artists have existed in Chinese history, they have remained marginal, little known and confined to a feminine aesthetic.1 Before the twentieth century, almost none of the artists indexed by Marsha Weidner realised portraits,2 and only few posed questions of identity through the execution of landscapes, a traditionally masculine genre.3 Beginning in the early twentieth century, a more pronounced feminism spread, including through various publications.4 The works of painter Wu Xingfen, whose real name was Wu Shujuan (1853-1930),5 seem to have marked the beginning of a certain recognition of female artists, particularly with her magazine covers for Funü zazhi [Ladies’ journal].6 Chinese women progressively freed themselves from the Confucian system,7 at times through the intermediary of westernisation.8 Between 1914 and 1955, 30 per cent of students accepted to the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris were women, including Pan Yuliang (1895-1977).9 A peer of painter Xu Beihong (1895-1953), she was saved from a brothel by the civil servant Pan Zhanhua, a supporter of Sun Yat-sen, whom she eventually married. Originally poorly received in China, her numerous nudes, some of which were published in magazines, can be simultaneously considered as a revolutionary act,10 the acceptance of the body, and a break with the “feminine aesthetic” in China.11 Was it therefore a strategy of taking charge of the female body and asserting women’s rights?12 In any case, during the Sino-Japanese war (1937-1945), the number of female artists that were emboldened, who no longer hesitated in throwing themselves into a more engaged art, multiplied. Yu Feng (1916-2007) and Liang Baibo (1911-c. 1970) attest to this enthusiasm. A student of Pan Yuliang,13 Yu Feng evolved in a literary and artistic milieu and was supported by her husband, artist Huang Miaozi (1913-2012). Her work invited women to actively participate in politics, suggesting that they free themselves from their shackles.14 Liang Baibo, was associated with the Shanghai artistic circle alongside Ye Qianyu (1907-1995) with whom she was in a relationship. She created the first female protagonist in a comic book, Miss Bee. Miss Bee was the female alter ego of Mr Wang – a character created by her partner – who became the representation of the modern women: richly dressed, westernised (notably because of her blonde hair) and independent. But do heroines such as Mulan or Miss Bee represent feminist figures? These heroines, whether old or new, were in reality stereotypical or subject to patriarchy. Mulan condemned herself to sacrifice in order to avoid disgrace befalling her family, while Miss Bee was as materialistic as she was scatterbrained. It seems, moreover, that most of the early female artists were known and recognized primarily because of their marital status and network, and not primarily for their talent.

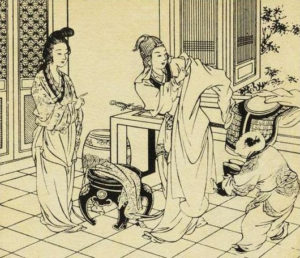

Wang Shuhui, extract from Mulan rejoint l’armée (木兰从军), 1956, © Right reserved

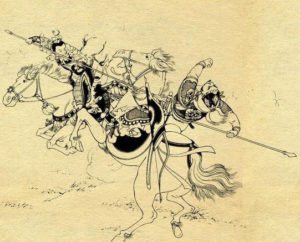

Wang Shuhui, extract from Veuves du clan Jiang (杨门女将), 1978, © Right reserved

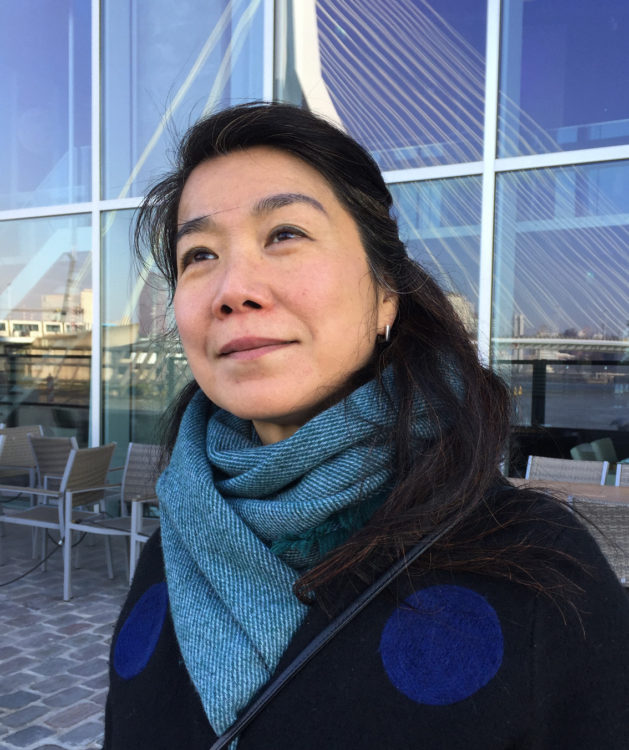

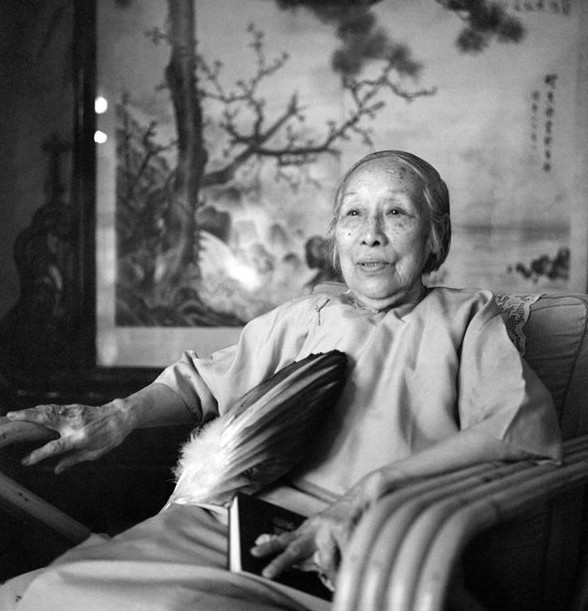

During the Maoist era, in spite of a feminist policy and egalitarian aspiratins, feminism remained a tool that nevertheless drew some criticism.15 Wang Shuhui (1912-1985), one of the rare female illustrators of lianhuanhua (traditional Chinese comic strips) endeavoured to heroize the woman, whether as warrior or courtesan. Although the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) damaged society both physically and symbolically, a wave of freedom seemed to sweep through with Deng Xiaoping after 1978, despite it being a political manoeuvre designed to make people forget the trauma of the past. The Deng government looked for new idols in women, their emancipation being synonymous with social progress. Wang Gongyi (b. 1946) and Jiang Caiping (b. 1934) consequently tried to portray heroines, in particular the revolutionary Qiu Jin,16 who came back to life after disappearing from the Chinese pantheon. Forgotten during the Cultural Revolution, she finally reappeared in the 1980s to consolidate the Deng government’s legitimacy.17 Thus, while the female model changed after Mao’s death, seemingly modernized, it was nonetheless still governed by a normative police force, often serving a propagandistic purpose according to the “Mulan syndrome” enunciated by Michael Sullivan.18 However, a new artistic scene emerged, one that emphasised “feminist art” (nüxing zhuyi yishu), as witnessed with the 1982 rediscovery of Pan Yuliang – who had been forgotten during the Maoist era – by a Chinese audience.19 Exhibitions of female artists have since multiplied. In 1990 the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing organised an exhibition focused on eight artists, including the young Yu Hong (b. 1966),20 although the approach served a political purpose.

Wang Gongyi, Passion from the series Qiu Jin, 1980, xylography, 60 x 56.5 cm, Oxford University, Ashmolean Museum, © Right reserved

Jiang Caiping, Qiu Jin, 1992, ink on paper, 290 x 290 cm, National Art Museum of China (NAMOC), © Right reserved

Sensual, comical, warlike and disillusioned, the portrayal of women by Chinese artists was subject to major changes and political vagaries in the twentieth century, so much so that feminism mixed with modernity in China. Thus, if Miss Bee, Mulan and others were stereotypical characters, they were nevertheless expressions of a certain criticism of a society that took the path of modernity through women as characters and actresses. The anti-Japanese resistance further engendered the desire for Chinese artists to free themselves from conservative oppression.21 As for communism, particularly under the rule of Deng Xiaoping, it initiated new reflections on women’s rights, despite the heroines being propagandists. Although China experienced several feminist movements, and despite the fact that women – in both their victimisation and heroization – sometimes seemed to be a tool in the hands of reformers, revolutionaries and the government, we would be wrong to judge too radically or hastily the creations of female artists.22 They often reflect a landmark of feminism. Indeed, this progress was made possible throughout the twentieth century particularly by female artists who were not content to fill “a few passive and silent roles”.23

Weidner Marsha, “Women in the History of Chinese Painting”, in Weidner Marsha (ed.), Views From Jade Terrace: Chinese Women Artists, 1300-1912, exh. cat., Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, 3 September-6 November 1988, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 6 December 1988-15 January 1989, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, 15 February-2 April 1989, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, 24 April-4 June 1989, Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 30 June-27 August 1989, Indianapolis, Indianapolis Museum of Art, New York, Rizzoli, 1988, p. 13 ; Sung Doris Ha Lin, “Redefining Female Talent: Chinese Women Artists in the National and Global Art Worlds, 1900-1970s”, PhD thesis under the direction of Joan Judge (Toronto: York University, 2016) pp. 6-7.

2

Weidner Marsha (ed.), op. cit.

3

Blanchard Lara C. W., “Imagining Du Liniang in The Peony Pavilion: Female Painters, Self-Portraiture, and Paintings of Beautiful Women in Late Ming China”, in Belli Bose Melia (ed.), Women, Gender, and Art in Asia, c. 1500-1900, New York, Routledge, 2016, p. 125.

4

Hockx Michel, Judge Joan and Mittler Barbara, Women and the Periodical Press in China’s Long Twentieth Century: A Space of Their Own?, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

5

Andrews Julia F. and Shen Kuiyi, The Art of Modern China, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, p. 57.

6

Ibid., p. 38; Sung Doris Ha Lin, “Redefining Female Talent”, p. 72.

7

The Confucian system, the traditional Chinese philosophy and morality, is characterised by significant paternalism and a respect for hierarchy.

8

Sung Doris Ha Lin, “Redefining Female Talent”, pp. 13-14. Since the end of the 19th century, the political situation in China has overlapped with the image of the male oppressor and the female victim. Chinese society has thus witnessed conservatism as the principle cause of its weakening: it feminises the nation that must reinforce itself through modernisation and westernisation, which is consequentially seen as a remasculanising process.

9

Cinquini Philippe, “Les Artistes chinois en France et l’École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris à l’époque de la Première République de Chine (1912-1949) : pratiques et enjeux de la formation artistique académique”, PhD thesis under the direction of Chang Ming Peng, université Lille 3 – Charles-de-Gaulle, 2017, p. 11.

10

Janicot Éric, “Le nu – un genre révolutionnaire”, L’Art moderne chinois, nouvelles approches, Paris, Éditions You Feng, 2007, pp. 115-124.

11

Sung Doris Ha Lin, “Redefining Female Talent”, p. 167.

12

This is a reflection proposed by author Chen Xiefen in 1903. See Pickowicz Paul G., Shen Kuiyi and Zhang Yingjin, Liangyou, Kaleidoscopic Modernity and the Shanghai Global Metropolis, 1926-1945, Leiden, Koninklijke Brill NV, 2013, p. 98.

13

Sullivan Michael, Modern Chinese Artists: A Biographical Dictionary (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006) p. 205.

14

Lent John A. and Ying Xu, Comics Art in China, Jackson, University Press of Mississippi, 2017, p. 36.

15

The author Ding Ling also criticises the hypocrisy of the Chinese Communist Party. See Menke Augustine, “The Development of Feminism in China”, PhD thesis and articles, under the direction of Eric Schluessel,Missoula, University of Montana, 2017, pp. 10-12, https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/164.

16

Qiu Jin was an anti-Qing feminist and revolutionary.

17

Ying Hu, “Qiu Jin’s Nine Burials: The Making of Historical Monuments and Public Memory”, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 19, no. 1, Spring 2007, p. 167.

18

Sullivan Michael, Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China,Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996, p. 219.

19

Sung Doris Ha Lin, “Redefining Female Talent”, p. 168.

20

Monica Merlin, interview with Yu Hong, 7 November 2013, published 20 March 2018, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/research-centres/tate-research-centre-asia/women-artists-contemporary-china/yu-hong; Lü Peng, Chinese Art in the 20th Century, trans. Bruce Doar, Paris: Somogy, 2013, p. 598.

21

Hung Chang-tai, War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937-1945, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1994.

22

See Zufferey Nicolas, “La condition féminine traditionnelle en Chine. État de la recherche”, Études chinoises, no. 22 (2003), pp. 185-229.

23

In the words of Nicolas Zufferey, although he is referring to Chinese women until the fall of the Qing Empire in 1911.

After studying at a literary preparatory school, Paul Narjoz-Delatour obtained a Master’s in Art History from the Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne in 2019. Recognised by the jury for his work on the Chinese engraver Zhao Yannian (1924-2014), he will participate in the development of a book in 2020 under the direction of Marie Laureillard, lecturer at the Université Lumière-Lyon 2, and Shiyan Li, Doctor of Humanities and the Arts at the University of Aix-Marseille. His research focuses on the relationship between art and politics in twentieth-century China.

Paul Narjoz-Delatour, "The Evolution of the Artistic Portrayal of Women by Chinese Female Artists in the 20th Century." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/evolution-de-la-representation-artistique-des-femmes-par-les-artistes-chinoises-au-xxe-siecle/. Accessed 23 April 2024