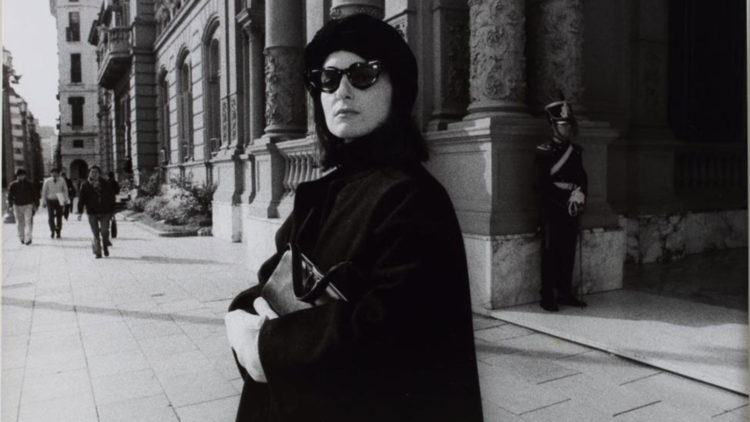

Yoshiko Shimada

Tan, Eliza, Yoshiko Shimada: Art, Feminism and Memory in Japan after 1989, PhD dissertation, Kingston University, 2016

→Yoshiko Shimada, Art Activism 1992–98, Tokyo, Ota Fine Arts, 1998

→Hiroko Hagiwara, “Comfort Women, Women of Conformity: The Work of Shimada Yoshiko”, in Griselda Pollock (ed.), Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts: Feminist Readings, New York, Routledge, 1996

Divide and rule: Yoshiko Shimada, A Space Gallery, Toronto, February 1–March 15, 1997

→Yoshiko Shimada, Keio University, Tokyo, December 19–23, 1996

→Gender, Beyond Memory: The Works of Contemporary Women Artists, Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo, September 5–October 27, 1996

Japanese feminist artist, activist and researcher.

The work of Yoshiko Shimada focuses on the socio-political tensions and historical amnesia after World War II. She investigates the complexity of gender roles and sexual and cultural identities concerning Japanese colonialism and imperialism with a wide range of artistic and scholarly practices, often delivered collaboratively. Her practices intersect with radical pedagogy, archival practice, political movements and spiritualism, unveiling the entanglement of Japanese modernity, patriarchy and discrimination of immigrants in post-war Japan.

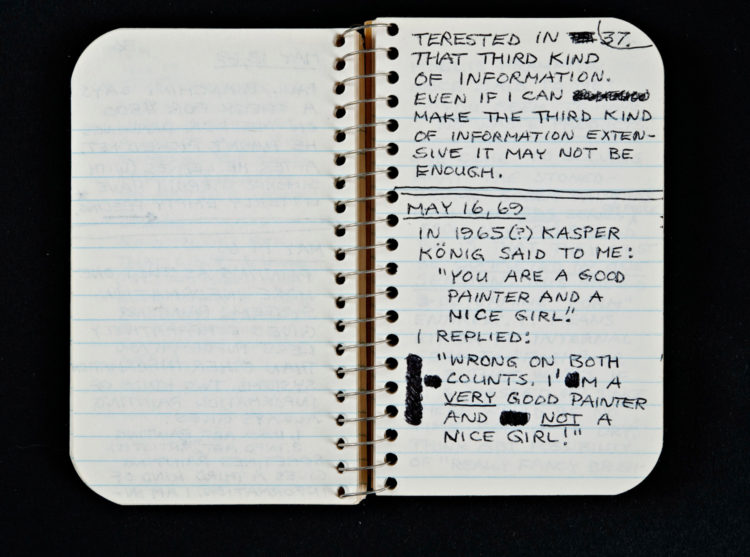

Y. Shimada studied fine arts in the United States and etching at the alternative art school Biggakō in Tokyo. Since the late 1980s she has explored issues regarding gender, sexuality, power and nation, especially how wartime ideology, history and memory have been perpetuated in present-day Japanese society. Later, in the 2000s, she became active as a researcher in Japanese avant-garde art movements and conceptualism regarding politics in the 1960s and 1970s. She received her PhD from Kingston University in the United Kingdom for her research on alternative and experimental art education. She also founded the archive of Yutaka Matsuzawa (1922-2006), a pioneer of conceptual art in Japan.

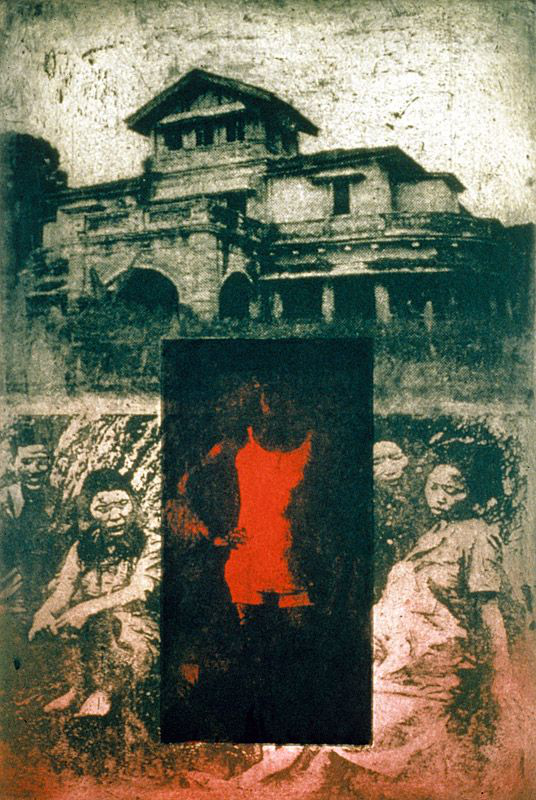

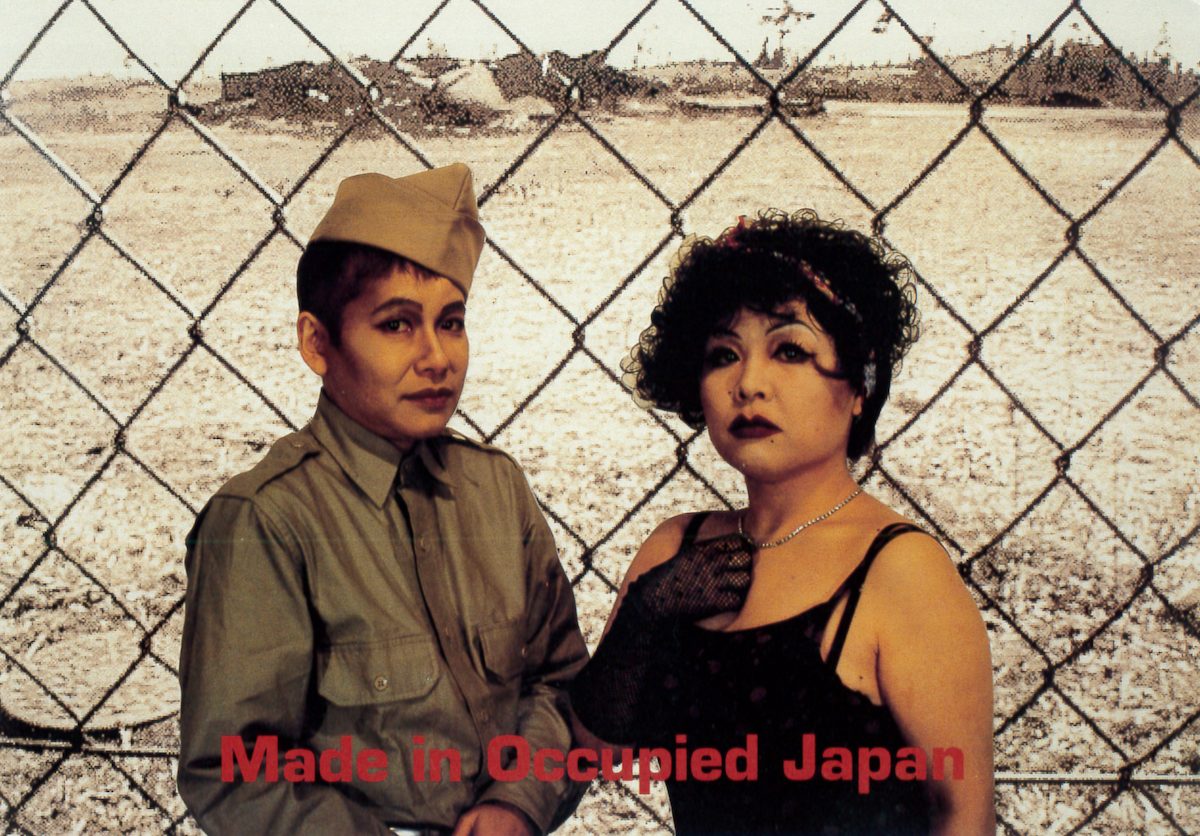

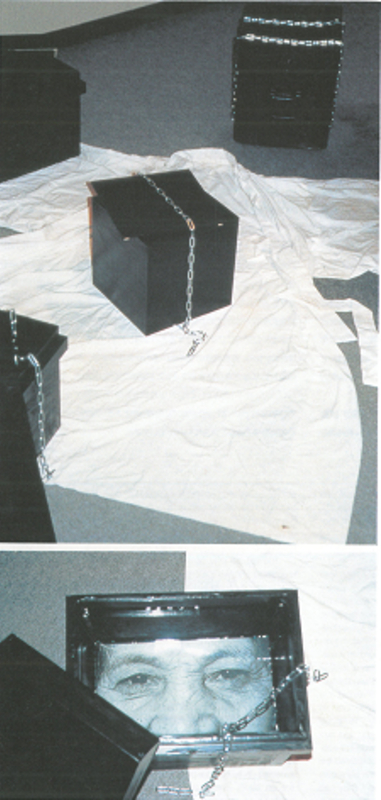

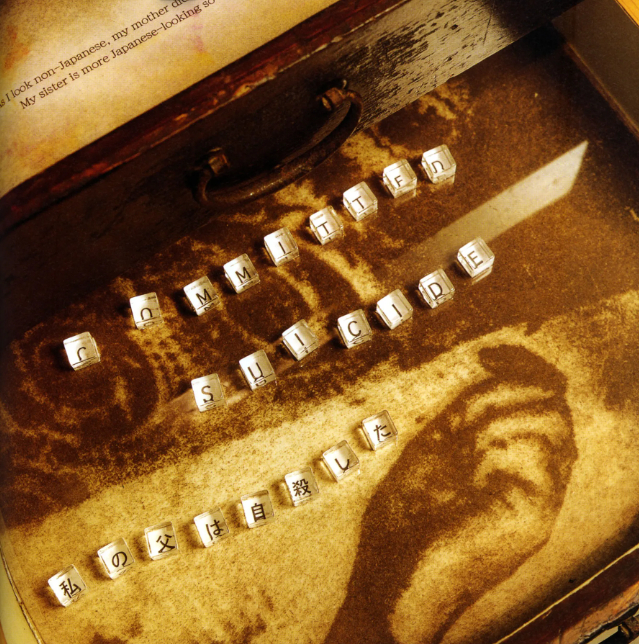

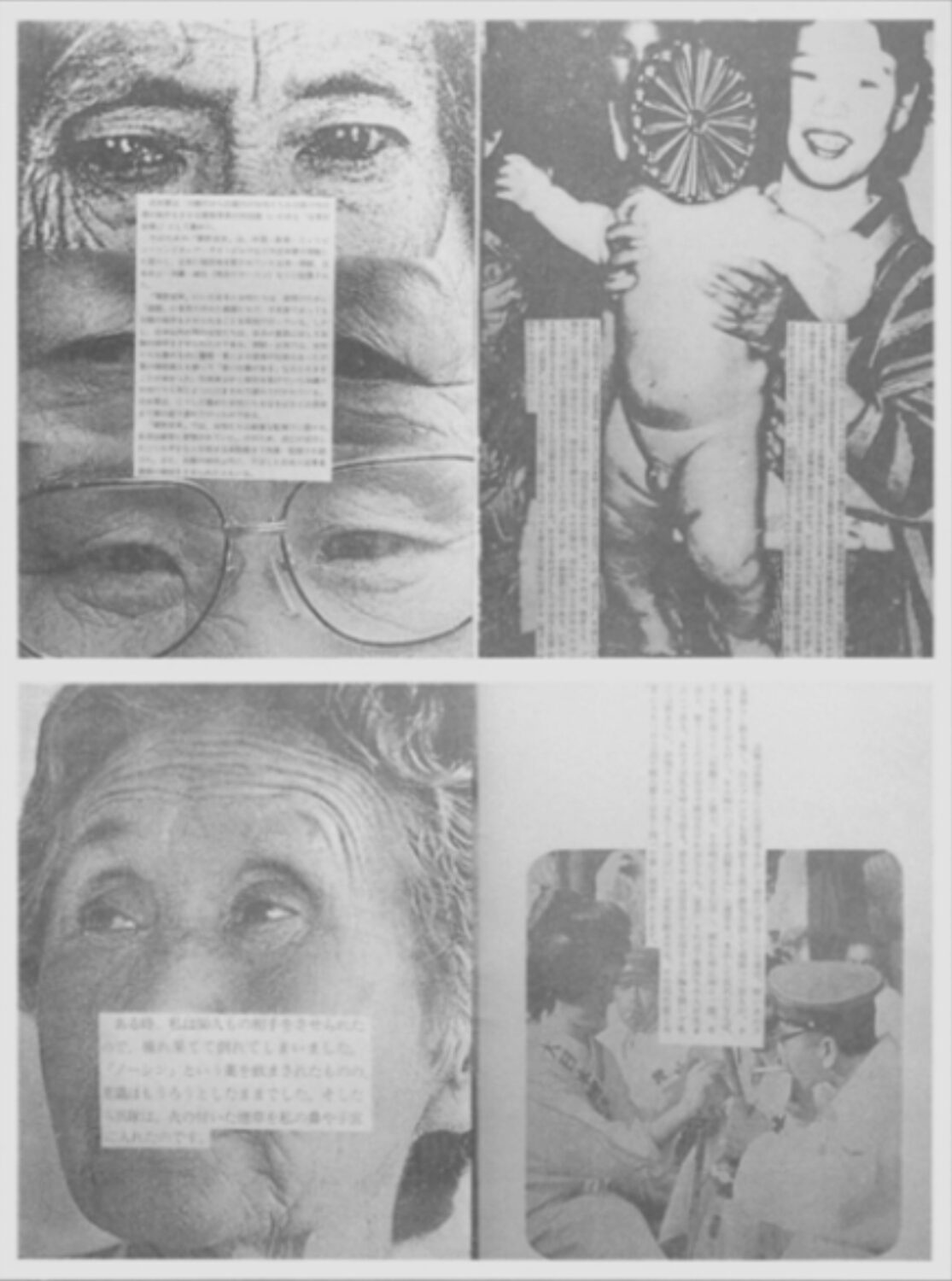

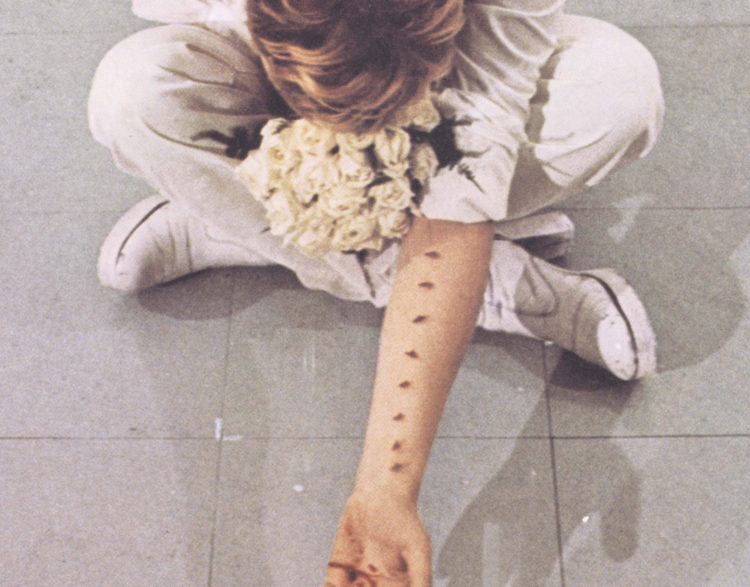

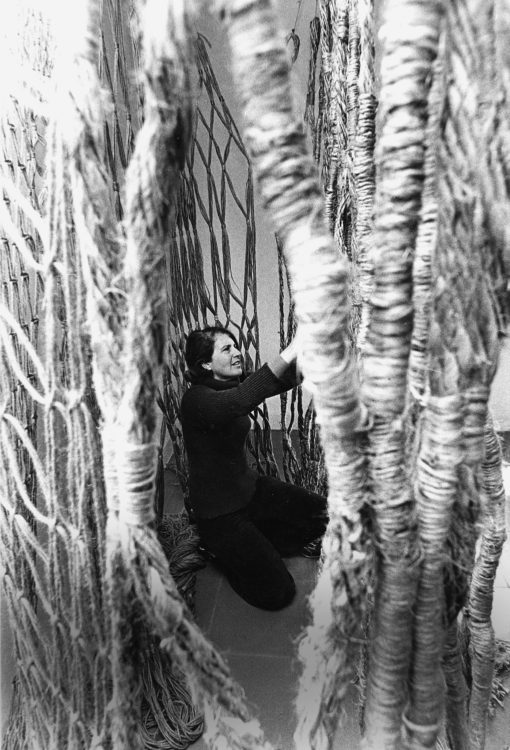

In her early etching series Past Imperfect (1991-1997), she explored women’s complicit role in the Pacific War. She challenged the glorified account of Japan’s wartime history by dealing with the issue of comfort women while reflecting on her positionality of being an Asian, Japanese and woman in relation to Asian communities and colonial entanglements. The series showcases contradictory images of women during the war: for example, she juxtaposed Japanese women in white aprons (kappōgi), which was a symbolic “uniform” of the caregiver in domesticity and purity of motherhood of the nation who strengthened the war effort with the suppressed presence of silenced Korean comfort women. This juxtaposition of the distinct women’s narratives in a manner of discursive intervention through the material sensibility became multifold to indicate how women were positioned differently regarding sexuality, ethnicity, class and nation. The complicities of positionality that her work addresses through an intersectional lens have been explored further in her curating exhibitions and the collaborative series Made in Occupied Japan (1998) with performance artist and activist BuBu de la Madeleine (b. 1961). The collaboration exposes the patriarchal power structure of Japanese society under the United States occupation by performing themselves, in drag, as the US soldiers, Japanese military prostitutes, housewives and Emperor Hirohito and Douglas MacArthur. Her practice also negotiates conflicts between personal memory and historical account without generalising them as nostalgic, for example, in Bones in Tansu: Family Secrets (2004) she invited visitors to enter a confession booth to write down their family secrets, which could be displayed as a part of the installation.

Responding to the ongoing political controversy over comfort women, she carried out the performance Being a Statue of a Japanese Comfort Woman (2012-ongoing) in public spaces, wherein Y. Shimada, in a Japanese kimono, painted her skin bronze and taped her mouth in reference to Statue of Peace, a bronze statue of a girl commemorating the Korean Comfort Women, implying twofold involvements of Japanese women, silenced voices and suppressed discussion. Consequently, her artwork has been targeted for censorship in the form of curatorial and institutional reluctance due to the conservative revisionist tendency in Japan. She made A Picture to be Burned (1993), an etching of Emperor Hirohito with his face scratched out, to protest against the censorship of the collage of the emperor produced by Ōura Nobuyuki (b. 1949), and she has problematised the issue of censorship, raising questions about the taboo regarding nationalism and sexism in Japanese society.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023