Prix AWARE

Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, © Photo: Grant Delin

Goddess of Memory

Barbara Chase-Riboud, born in 1939, describes how she resolutely turned to sculpture as a child: by the age of seven, she was enrolled in classes at the Philadelphia Museum and the Fleisher Art Memorial, where she was awarded the sculpture prize in the adult evening class section. At 16, one of her works was purchased by William S. Lieberman, despite the fact that he knew nothing about her at the time, and later gifted to MoMA; the museum now holds four of her works, one of them on permanent display. The sculpture was shown at the ACA Galleries in New York, after Barbara Chase-Riboud won a contest organised by Seventeen magazine. Determination, and being something of a child prodigy – although this implies recourse to certain kind of narrative logic, whereas the artist herself phrases it in much simpler terms: she had always wanted to create sculptures – a small Grecian-style vase at the age of seven, a woodcut at sixteen – but to her, this was an integral part of her life, her practice and her catalogue raisonné, on a par with what was yet to come and is still ongoing today. And her creations of yesterday, her childhood achievements, are no less valuable.

Barbara Chase-Riboud, Mao’s Organ, 2007, polished bronze and red silk cord, © Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC NY, © Barbara Chase-Riboud

Barbara Chase-Riboud, Zanzibar Table Gold, 1972, bronze poli, soie et lin, 38,7x 33 x 32,4 cm, courtesy Barbara Chase-Riboud ,© Barbara Chase-Riboud

On to the late 1950s: Barbara Chase-Riboud travels to Italy, Egypt, Greece and Turkey, guided by faith in encounters and opportunities, serendipity and daring experiments. The places where she lived and travelled to nourish a formal imagination already forged by classical sculpture and the Baroque, drawing her towards the horizons of non-Western sculpture. She has described the twelve months she spent in Italy, from 1957, as “magical”: in 1958 she took part in the first Festival dei Due Mondi in Spoleto with a solo exhibition; she sold a sculpture to an artist she admired, Ben Shahn, and met Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Mimmo Rotella and Domenico Gnoli. In Egypt she also got to know René Burri. To earn her living she worked at the Cinecittà Studios in Rome, mainly designing sets for Hollywood epics. By doing all sorts of odd jobs during the filming of Ben Hur she was able to set herself up and start working with the Bonvicini Foundry in Verona. However, Barbara Chase-Riboud is also a writer. As she explains, this range of artistic pursuits means that she has always managed to achieve an economic balance. In the 1970s, for instance, when she was not yet able to live off the sale of her sculptures, the success of her publications ensured a comfortable income.

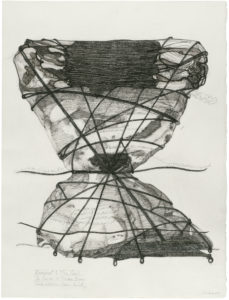

Barbara Chase-Riboud, Monument to Man Ray’s The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse Philadelphia, 1996, charcoal, charcoal pencil, ink with engraving and aquatint on paper, 80 x 60.3 cm, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, © Barbara Chase-Riboud

Barbara Chase-Riboud published her first novel in 1979, after discovering the story of Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson, the story of a relationship between an African-American slave and a former president of the United States. It was Toni Morrison, her editor at Random House (which had published her collection of poems, From Memphis & Peking, in 1974), who persuaded her to translate her obsession with this story into writing. Sally Hemings: A Novel was published in France in 1981 under the title La Virginienne. Despite being a work of fiction it created a scandal, particularly among certain historians, who claimed there was no foundation for the alleged relationship and denied the existence of the couple’s children. Barbara Chase-Riboud won the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for her novel, which sold over one million copies all over the world.

Barbara Chase-Riboud, All That Rises Must Converge Red, 2008, red bronze, silk and synthetic silk, 187.96 x 106.68 x 71.12 cm, Collection particulière, © Barbara Chase-Riboud

In nominating Barbara Chase-Riboud for the AWARE Outstanding Merit Prize, we were struck by the relatively modest coverage given to her work in France today. Several years ago, when I discovered – and immediately fell in love with – her creations, I tried in vain to find a monograph in French or to track down a permanent display of her works in a Parisian arts institute, while hoping that a retrospective would be held somewhere in France. Curiously, Barbara Chase-Riboud’s oeuvre had nevertheless been highlighted by Suzanne Pagé at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris/ARC in the 1970s, she was made Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres in 1996, and two of her sculptures, acquired in 1972 and 1984, now belong to the collections of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP). At the outset, this is clearly a structural issue. Not only was it the destiny of most women artists in the 1960s but also that of an African-American woman in France, a woman whose sculptural oeuvre was neither minimal nor conceptual, a woman who was also a renowned poet and author, a woman whose art was political, and a woman who from the early 1960s to the early 1980s also happened to be the wife of French photographer Marc Riboud.

Barbara Chase-Riboud, The Albino, 1972, bronze with black patina, wool and other fibers, 457.2 x 320 x 76.2 cm, MoMA, © Barbara Chase-Riboud

This said, the sculptural œuvre of Barbara Chase-Riboud is both epic and unforgettable, and it is on that note that I must obviously bring this tribute to a close: over seventy years of prolific, intense and concentrated creation, sometimes monumental, sometimes rising to the challenge of permanence in the public space. A sculpture with its own unique lexicon, which circumvents the plinth, colours the bronze, knots the silk, engages in dialogue with the poems, summons the past and pays homage, over and over again (as in the series of steles dedicated to Malcolm X, inaugurated in the late 1960s). The 5-metre high Africa Rising (1998), Barbara Chase-Riboud’s largest sculpture, is located in the lobby of the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway in New York, and is dedicated to Sarah Baartman. The monument was commissioned by the US General Services Administration in 1996. In the wake of the death of George Floyd in May 2020, within the framework of the mooted dismantling of statues celebrating white supremacy and colonialism, Barbara Chase-Riboud suggested replacing the equestrian statue depicting a triumphant Theodore Roosevelt and erecting Africa Rising on the same spot, at the entrance to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Eva Barois De Caevel

Barbara Chase-Riboud was born in 1939 in Philadelphia (Pennsylvania, USA). She lives and

works in Paris, Rome and Milan. A sculptor, poet and novelist, Barbara Chase-Riboud began her artistic training at the age of seven, at the Philadelphia Museum and the Fleisher Art Memorial. She was just sixteen when the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York acquired one of her first works. She studied at Temple University and Yale, where she was the first African-American woman to gain a Master’s degree from Yale School of Architecture. She created her first bronze sculptures, and held her first solo gallery shows, in Rome from 1957 to 1959, when she also visited Paris, Egypt, Greece and Turkey, expanding her artistic horizons beyond the Western tradition. She settled in Paris in 1961 and married French photographer Marc Riboud. Her artworks have since been widely exhibited at institutions in the US, France, Japan, Australia, Germany and more. Barbara Chase-Riboud is also well known for her literary work. She published her first collection of poetry, From Memphis & Peking, to widespread critical acclaim in 1974. Her first novel, Sally Hemings, appeared in 1979. She has published some ten novels and collections of poetry, and has received numerous awards for her fiction, including the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize. Works by Barbara Chase-Riboud feature in the permanent collections of the following major art institutions: Berkeley Art Museum (California); the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York); the Museum of Modern Art (New York); the Newark Museum (New Jersey); the New Orleans Museum of Art (Louisiana); the New York Historical Society Museum (New York); the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Pennsylvania); the Smithsonian African American Museum (Washington D.C.), the Studio Museum in Harlem (New York), the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (France).

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.