Prix AWARE

© Galerie Oniris – Rennes

A lyrical homage/damage to the artist with the three “con-”1: Vera Molnár

One morning in the mid-2000s, Leo J. M. Koenders, a collector and member of the “Zurich readers of Ulysses” circle, called Vera Molnár to commission a tribute book from her in memory of James Joyce. Vera Molnár, an artist usually little accustomed to answering the call of commissioners – having refused for many years to show her work, instead favouring a more dematerialised form of art and thus maintaining a conceptualist orientation –, chose to accept the unexpected proposal.

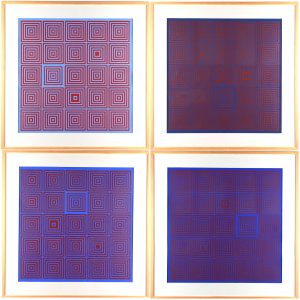

Vera Molnár, 1% de désordre bleu et rouge (A, B, C et D), 1974-1978, painting on paper, quadriptych, 4 x 50 x 50 cm, Courtesy Vera Molnár, © Galerie Oniris, Rennes, © ADAGP, Paris

Against all odds, she tackled the Leopold Bloom angle, even if it felt very remote from the austere and rigoristic – constructivist and conceptual – aura that surrounded her work. The complete opposite of the ascetic intellectual Stephen Dedalus, Bloom is a Jewish advertising agent driven by his carnal desires. Like Molnár, he was born in Hungary. Coincidentally with their Hungarian origins, B-L-O-O-M – V-I-R-A-G in the original text – was born in the town of Szombathely. The artist created sixteen studies, following her customary scientific method and refusal of any form of mysticism. The variations in the position of the letter-signs are reminiscent of Joyce’s systemic and fascinating way of, according to Jacques Aubert, “giving language an enigmatic density”, “lacing words with apprehension” and “injecting silence with a certain tumult”.2 By evoking a displacement that materialises a line from East to West, Vera Molnár gives us an underlying insight into Joyce’s bizarre tangent – a form of anarchy in the repetitive task of constructivism.3

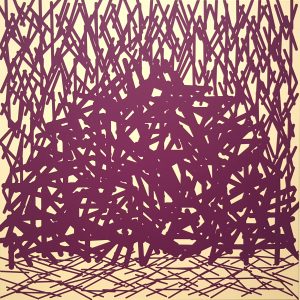

Vera Molnár, Meule, la nuit – P, 1977-2013, acylic on canvas, 80 x 80 cm, Courtesy Vera Molnár, © Galerie Oniris, Rennes, © ADAGP, Paris

Letters to my mother (1981-1990) is yet another iconoclastic work in Vera Molnár’s career. In it, she reproduces her mother’s handwriting, which, according to Molnár, was “an important event in [her] visual world”4 before she died. The Hungarian mother and her naturalized French daughter wrote every week: “My mother’s handwriting was beautiful. Slightly gothic and also a little hysterical.”5 Again, the artist’s personal history – marked by chosen exile motivated by the will to create, but nevertheless experienced in the political setting of popular trials – is the starting point of a process. In this case, it transmutes the disembodiment of the loved one into a familiar series specific to the artist’s discipline: from imaginary machine to cybernetic algorithms, the lines drawn are reminiscent of the lines of a seismograph measuring the interval produced by the introduction of disorder (hysteria) into an organised situation (Gothicism). Like the repetitions and variations of the letter M – M like Malevich or Mondrian –, which can cover both the whole surface of the page of a “livrimage” (“picturebook”) and of an all-over, Vera Molnár injects error, malformation, and damage into her structured repartition as an homage to the two masters of abstraction. A sort of “modular stutter”, a “fractal drunkenness”, a geometric “somersault”,6 which the artist inventories in her text Je m’aime.

The filiation between Vera Molnár and the currents of French abstraction or of a certain form of French minimalism7 can only be considered today in regards to the rigour with which the artist applies herself to disseminating a form of disobedience at the very heart of historiographical canons. Vera Molnár has consistently sought to distance herself from the codes of visual culture. However, rather than achieve this distance through scrupulous dogmatism, she has chosen to do so with joyful asceticism and playful rigour.

During World War II, Vera Molnár (1924, Hungary) was a student at the School of Fine Arts in Budapest. She quickly decided to become a painter and moved to Paris in 1947. Impressed by the paintings of Georges Braque, Jean Hélion, and Paul Klee, she embarked on a quest for simplicity, in contrast with lyrical and mystical abstraction. She became deeply interested in computer programming as from 1968 and returned to hand-drawing fundamental shapes in the 1990s. Her works are featured in a large number of international public collections, including the CNAP and musée national d’Art moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou. Her work has been shown at the Credac (Ivry-sur-Seine), 49 Nord 6 Est – FRAC Lorraine (Metz), Grenoble Museum, Grand Palais, Digital Art Museum (DAM, Berlin), Ludwig Múzeum (Budapest), and many others. A retrospective of her work was held at the musée des Beaux-Arts in Rouen and Contemporary Art Centre in Saint-Pierre-de-Varengeville in 2012.

Vera Molnár defines her work as a cross between constructivism, conceptualism, and computer.

2

Aubert Jacques, “Heureux qui comme Ulysse… L’Ulysse de James Joyce”, Les Chemins de la philosophie radio programme, France Culture, 27 October 2014.

3

Baby Vincent, “Introduction”, in the exh. cat. Vera Molnár. Une rétrospective, 1942-2012, musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, 2012, Paris, Bernard Chauveau éditeur, 2012.

4

“She wrote to me weekly, and it was a important series of events in my visual world.” Online, URL: http://www.veramolnar.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/VM1991_lettres.pdf

5

Ibidem.

6

Molnár Vera, Je m’aime, in the exh. cat. Vera Molnár. Inventaire, 1946-1999, Ladenburg, Preysing, 1999, p. 89.

7

Lemoine Serge, “Vera Molnár, reConnaître”, in the exh. cat. Vera Molnár, musée de Grenoble, Grenoble, 2001-2002, Paris, RMN, Grenoble, musée de Grenoble, 2001.

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.